Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have established stronger limitations on the power of shallow quantum circuits, proving that certain fundamental functions remain computationally challenging even with quantum speedups.

This work demonstrates tighter lower bounds for QAC0 circuits, showing that depth-2 circuits are insufficient for preparing generalized nekomata states and computing PARITY or MAJORITY functions efficiently.

Despite decades of research, demonstrating a clear quantum advantage-even for restricted computational models-remains a significant challenge. This work, ‘Improved Lower Bounds for QAC0’, establishes stronger limitations for shallow quantum circuits, specifically demonstrating that constant-depth quantum computation-even with polynomially many ancillae-cannot efficiently compute functions like PARITY or MAJORITY, nor synthesize certain quantum states. These results are achieved through novel classical simulation techniques and refined lower bound arguments, revealing a surprising correspondence between the power of quantum and classical circuits for inherently classical decision problems. Do these findings suggest that achieving a practical quantum advantage requires significantly deeper or more complex quantum architectures?

The Boundaries of Classical Simulation

Classical computers, despite their remarkable progress, struggle fundamentally with accurately modeling even modestly complex quantum systems. The core of this limitation lies in the exponential growth of the computational resources required to represent a quantum state. While a classical bit stores a 0 or 1, a quantum bit, or qubit, exists in a superposition of both, necessitating a proportional increase in classical bits to describe it. As the number of qubits increases, the classical representation explodes – $2^n$ classical bits are needed to represent the state of $n$ qubits. This quickly renders simulations intractable, even with the most powerful supercomputers, highlighting the inherent scalability challenges in using classical computation to understand and harness the full potential of quantum mechanics. This isn’t merely a matter of needing faster hardware; it’s a fundamental constraint imposed by the nature of quantum information itself.

The representation of quantum states presents a fundamental challenge to classical computation due to the exponential growth in resources needed as the system’s complexity increases. Unlike classical bits, which exist as either 0 or 1, a quantum bit, or qubit, can exist in a superposition of both states simultaneously. Describing a system of n qubits requires specifying $2^n$ complex amplitudes, meaning the amount of information needed grows exponentially with the number of qubits. This quickly becomes intractable; simulating even moderately sized quantum systems demands memory and processing power that rapidly exceed the capabilities of even the most powerful supercomputers. Consequently, while classical computers can simulate small quantum systems, this scalability bottleneck severely restricts their ability to model complex phenomena relevant to fields like materials science, drug discovery, and advanced cryptography, driving the search for quantum computational solutions.

The quest to define the boundaries of efficient computation drives ongoing research into lower bounds on circuit depth – a measure of the number of logical gates needed to solve a problem. Establishing these limits isn’t merely an academic exercise; it reveals fundamental constraints on any computational model, classical or quantum. Researchers investigate specific problems, attempting to prove that no algorithm, regardless of ingenuity, can solve them with a circuit depth below a certain threshold. These proofs often rely on techniques like adversary arguments or barriers derived from information theory. Successfully demonstrating such lower bounds provides crucial insight into the inherent difficulty of computational tasks, guiding algorithm design and helping to pinpoint where quantum computation might offer a genuine advantage, and conversely, where classical approaches will always struggle. This pursuit ultimately shapes the landscape of what is computationally feasible and informs the development of both algorithms and hardware.

A thorough comprehension of the boundaries faced by classical computation is not merely an academic exercise, but a foundational necessity for progress in quantum algorithm design. Determining where classical systems falter allows researchers to pinpoint the specific problems where quantum computation offers a genuine advantage, guiding the development of algorithms tailored to exploit these capabilities. This assessment extends beyond simply demonstrating a quantum speedup; it requires a nuanced understanding of the resources – such as circuit depth and qubit count – needed to achieve that speedup, and whether those resources remain practical as problem sizes increase. Ultimately, establishing these limits is paramount to accurately gauging the true potential of quantum computers and directing investment towards algorithms and hardware with the highest likelihood of delivering impactful results, rather than pursuing solutions that remain perpetually out of reach.

Constraining Quantum Circuit Depth: A Path to Tractability

Current research efforts are focused on characterizing the computational capabilities of shallow quantum circuits, specifically those with a depth of 2 and 3, denoted as Depth2QAC0 and Depth3QAC0 respectively. This restriction in circuit depth serves to reduce the computational space and allows for more tractable analysis of potential algorithms. Investigations into these circuits involve determining which computational problems can be efficiently solved within these depth limitations, and establishing lower bounds on the resources required to perform specific tasks. The goal is to understand the fundamental limits of shallow quantum computation and its potential advantages over classical computation for particular problem classes.

Restricting quantum circuit depth to a limited number of layers, such as depth 2 or 3, significantly reduces the size of the algorithm search space. The number of possible quantum circuits grows exponentially with depth; therefore, analyzing shallow circuits is computationally feasible in ways that analyzing deeper circuits is not. This constrained exploration allows researchers to systematically investigate the capabilities of quantum algorithms within a tractable parameter range, facilitating the identification of specific computational tasks achievable with limited resources and providing a foundation for understanding the relationship between circuit depth and computational power. By focusing on shallow circuits, researchers can develop and test analytical techniques and derive meaningful results regarding quantum computational complexity.

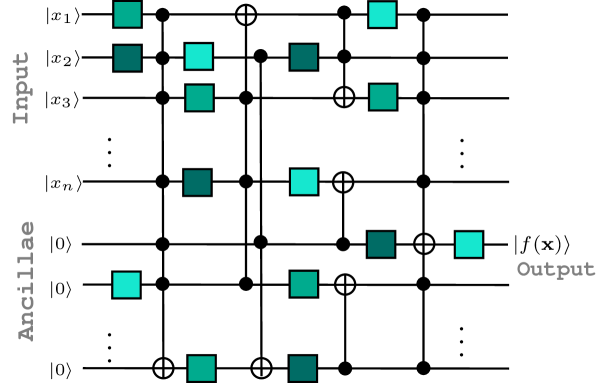

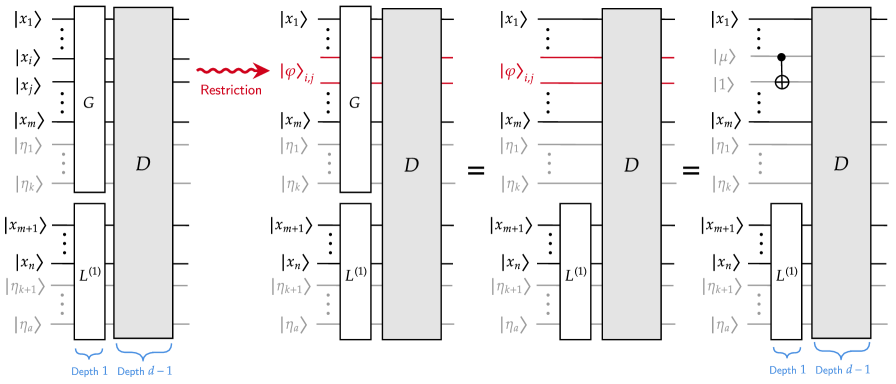

Circuit simplification techniques, such as the CleanUp Lemma and Classical Restriction, are crucial for analyzing quantum algorithms with limited depth. The CleanUp Lemma allows for the reduction of a quantum circuit by iteratively removing reversible gates that do not alter the output, while preserving computational power. Classical Restriction involves fixing certain qubits to classical values during computation, effectively reducing the Hilbert space dimension and simplifying the circuit’s state space. Both techniques enable researchers to derive analytical results and lower bounds on circuit complexity by reducing the computational burden of analyzing large quantum circuits, particularly within the constrained depth regimes of circuits like Depth2QAC0 and Depth3QAC0.

Restricting quantum circuit depth to a manageable number of layers, such as depth 2 or 3, enables the application of formal methods to analyze computational complexity. This approach facilitates the derivation of lower bounds on the resources – specifically, the number of gates or qubits – required to perform certain computations. Techniques like circuit simplification and the application of the CleanUp Lemma allow researchers to reduce complex circuits to a minimal form, against which computational cost can be accurately assessed. Consequently, limitations on circuit depth provide a pathway to establish definitive statements about the inherent difficulty of quantum algorithms and to benchmark their performance against classical counterparts, offering insights into potential quantum advantage.

Lower Bounds and Computational Hardness: Defining the Limits

A central objective of this work is to prove that computing certain Boolean functions, notably the $PARITY$ function, necessitates quantum circuits with a depth exceeding that achievable by circuits limited to two or three layers. The $PARITY$ function, which returns true if and only if an odd number of its inputs are true, is known to be difficult for shallow circuits in the classical setting. Establishing a similar lower bound in the quantum realm demonstrates that quantum computation does not inherently offer a substantial advantage for all Boolean functions when restricted to shallow circuit depths, and highlights the necessity of deeper circuits for functions like $PARITY$. This investigation aims to precisely quantify the minimum circuit depth required for these functions, thereby providing a baseline for assessing the capabilities of quantum algorithms.

This work demonstrates a lower bound on the circuit depth required to compute specific Boolean functions. Specifically, it is proven that the PARITY and MAJORITY functions cannot be computed by quantum circuits with a depth of 3. This establishes that any quantum algorithm implementing these functions must necessitate a circuit depth greater than 3, thereby confirming a non-trivial lower bound on computational complexity for these functions and ruling out the possibility of shallow circuit implementations.

Establishing that Boolean functions such as PARITY and MAJORITY cannot be efficiently computed by circuits with limited depth-specifically, shallow circuits-directly implies a lower bound on the minimum circuit depth required for their computation. This principle is fundamental in computational complexity theory; demonstrating the impossibility of realizing a function with a circuit of a given structure necessitates a more complex-and therefore deeper-circuit for its realization. A lower bound of $k$ for a function $f$ means any quantum circuit computing $f$ must have a depth of at least $k$, regardless of other parameters like the number of qubits or gates. This contrasts with upper bounds, which demonstrate that a function can be computed with a circuit of a certain depth, but don’t preclude the existence of more efficient circuits.

The total influence of depth-2 quantum circuits composed of $QAC^0$ gates is demonstrably limited to $O(\log n)$, where $n$ represents the number of input variables. Total influence, a metric quantifying the sensitivity of a function to changes in its inputs, provides a quantitative assessment of the circuit’s expressive power. This bound indicates that even with all possible gate combinations within a depth-2 $QAC^0$ circuit, the function’s sensitivity to input changes cannot grow beyond logarithmic order with respect to the input size. Consequently, functions requiring higher sensitivity to compute – such as those exhibiting significant input dependence – cannot be efficiently realized by circuits of this type, establishing a clear limitation on their computational capacity.

Constructible States and Their Properties: Exploring the Realm of Entanglement

Quantum computation relies on the manipulation of entangled states, but creating complex states efficiently remains a significant challenge. Researchers are focusing on specific, well-defined entangled states – notably the Nekomata state and its generalizations – as test cases to determine the limits of “shallow circuit” construction. Shallow circuits, those requiring only a few sequential operations, are particularly desirable due to their potential for implementation on near-term quantum hardware. By investigating what types of entangled states can be reliably built using these limited circuits, scientists gain crucial insight into the capabilities and constraints of emerging quantum technologies. The Nekomata state, with its unique entanglement properties, serves as a valuable benchmark for assessing the efficiency of various quantum compilation and synthesis techniques, ultimately guiding the development of practical quantum algorithms and architectures.

The exploration of complex quantum states, such as the Nekomata State, frequently involves a technique called separable post-selection, which yields Generalized Nekomata States (GNSP). This process essentially filters the outcomes of a quantum computation, accepting only those results that satisfy a specific, classically verifiable condition. While this ‘selection’ doesn’t change the underlying quantum mechanics, it dramatically alters the observed state, effectively creating a new state – the GNSP – with properties distinct from the original. Researchers utilize post-selection because it can simplify the creation of otherwise inaccessible states, allowing for a more tractable investigation of entanglement and quantum computation, although at the cost of probabilistic success – only a fraction of attempts will yield the desired GNSP.

A fundamental question in quantum information science concerns the compositional nature of complex quantum states – specifically, whether intricate entanglement can emerge from the combination of simpler, non-entangled, or separable states. Researchers are actively investigating if these complex states, such as Generalized Nekomata States, can be decomposed into basic building blocks, akin to constructing a complex structure from LEGO bricks. Determining this relationship isn’t merely an academic exercise; it directly impacts the feasibility of creating and manipulating these states in a quantum computer. If complex states can be built from simpler ones, it suggests more efficient methods for their construction and control. Conversely, if they require fundamentally different resources, it highlights the inherent limitations of certain quantum computational approaches and necessitates the exploration of novel techniques for generating and utilizing quantum entanglement.

Recent research establishes a fundamental constraint on the creation of complex quantum states using shallow circuits. Specifically, the study demonstrates that circuits with a depth of only two quantum gates – a measure of their computational complexity – are demonstrably incapable of synthesizing a Generalized Nekomata State (GNSP). This finding is significant because GNSPs represent a class of entangled states actively explored for potential advantages in quantum computation. The inability to construct these states with minimal circuit depth underscores a limitation in the efficiency of shallow circuit constructions, suggesting that achieving complex entanglement requires a greater degree of computational resources than previously anticipated and guiding future investigations towards more sophisticated circuit designs.

The pursuit of efficient quantum computation, as detailed in this work concerning QAC0 circuits, echoes a fundamental principle of elegant design. The paper rigorously demonstrates limitations in shallow circuit depth for functions like PARITY and MAJORITY, revealing a necessary complexity for their realization. This echoes a sentiment articulated by Richard Feynman: “The first principle is that you must not fool yourself – and you are the easiest person to fool.” The authors don’t simply assume shallow circuits are sufficient; they meticulously expose their inadequacies through Fourier analysis and state preparation limitations. This commitment to honest evaluation-to understanding what cannot be done-is paramount, and ultimately leads to a deeper appreciation of the underlying structure of computation itself. Consistency in these lower bound proofs, a form of empathy for future researchers, provides a solid foundation for continued exploration.

Further Horizons

The demonstration that even modestly complex functions resist efficient realization within shallow quantum circuits – and that preparing seemingly simple states requires surprising depth – feels less like a culmination and more like a sharpening of the question. The pursuit of lower bounds, it turns out, isn’t about erecting insurmountable barriers; it’s about meticulously mapping the contours of computational possibility. The limitations revealed here for QAC0 do not suggest an end to shallow-circuit quantum computation, but rather a need for finer-grained understanding of what can be achieved, and, crucially, what tools are needed to prove it.

One observes that the techniques employed – Fourier analysis, careful state construction – while effective, remain somewhat ad-hoc. A more elegant framework for relating circuit depth to function complexity is surely desirable. The connection between lower bounds and the inherent symmetries of the problems considered warrants further investigation; functions lacking obvious structure may require entirely different approaches.

The preparation of generalized nekomata states, in particular, feels like a partially explored landscape. The fact that depth-2 circuits fall short suggests a subtle interplay between entanglement and state preparation, a relationship that demands closer scrutiny. The aesthetic appeal of minimal circuits should not distract from the fundamental question: can a genuinely useful quantum computation be performed with deceptive simplicity, or is depth an unavoidable cost of power?

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2512.14643.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Mewgenics Tink Guide (All Upgrades and Rewards)

- Jujutsu Kaisen Modulo Chapter 23 Preview: Yuji And Maru End Cursed Spirits

- 8 One Piece Characters Who Deserved Better Endings

- Top 8 UFC 5 Perks Every Fighter Should Use

- How to Play REANIMAL Co-Op With Friend’s Pass (Local & Online Crossplay)

- One Piece Chapter 1174 Preview: Luffy And Loki Vs Imu

- How to Discover the Identity of the Royal Robber in The Sims 4

- How to Unlock the Mines in Cookie Run: Kingdom

- Sega Declares $200 Million Write-Off

- Full Mewgenics Soundtrack (Complete Songs List)

2025-12-17 19:06