Author: Denis Avetisyan

A novel encryption technique leverages the computational complexity of Sudoku puzzles to safeguard images, audio, and video data against modern attacks.

This review details a new multimedia encryption method using Sudoku-based algorithms, enhancing security by exploiting the NP-complete nature of the puzzle’s solution.

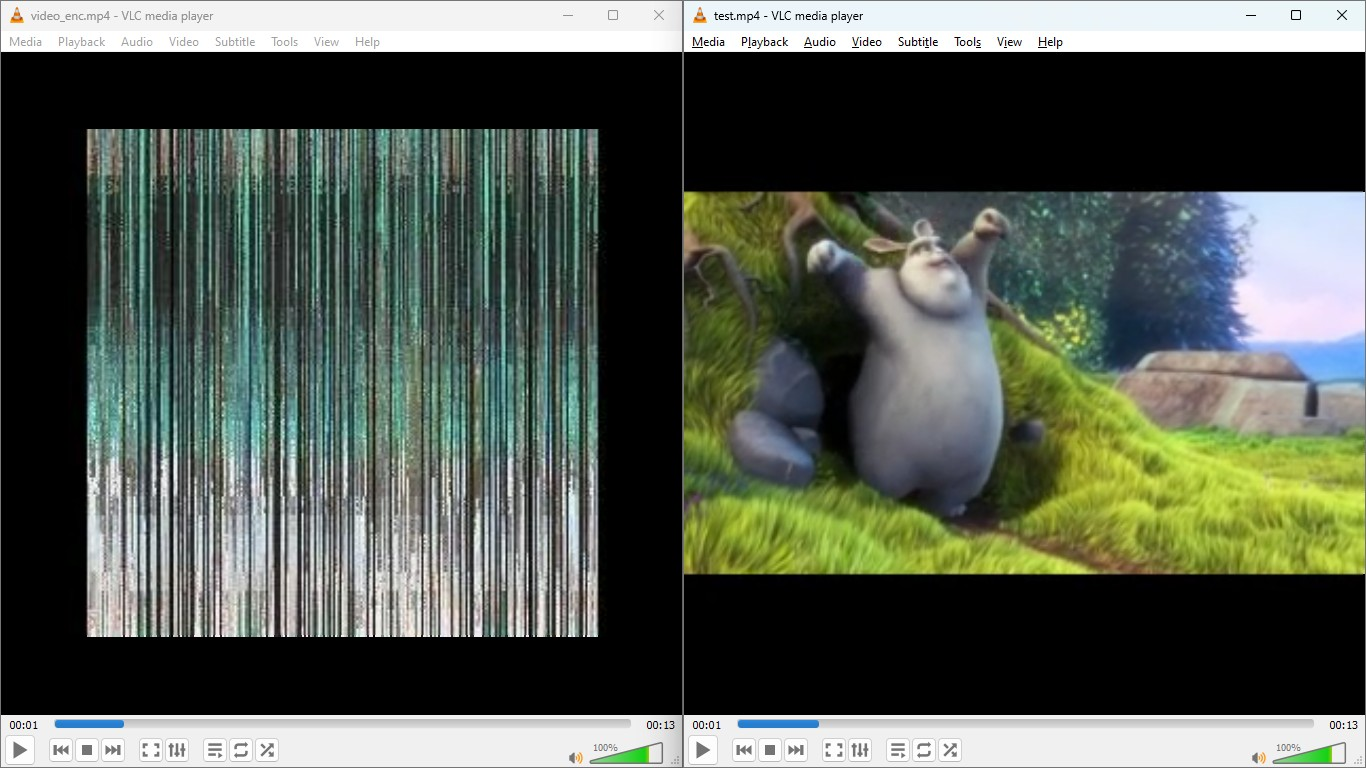

Despite increasing reliance on digital multimedia, securing sensitive data against evolving cyber threats remains a significant challenge. This is addressed in ‘Advanced Encryption Technique for Multimedia Data Using Sudoku-Based Algorithms for Enhanced Security’, which proposes a novel encryption method leveraging the computational complexity of Sudoku puzzles for enhanced security across image, audio, and video formats. The system demonstrates strong resistance to common attacks-achieving near-perfect NPCR values for images and exceeding 60dB SNR for audio-by employing both transposition and substitution ciphers keyed to transmission timestamps. Could this approach offer a viable pathway towards more robust and adaptable multimedia encryption solutions in an era of escalating data breaches?

The Illusion of Encryption: A Modern Conundrum

Full encryption, while historically a cornerstone of data security, presents significant challenges in modern computing environments. The process of transforming every bit of data into an unreadable format demands substantial processing power and memory, creating a bottleneck for applications and systems. This computational expense becomes particularly acute with the increasing volumes of data generated daily and the need for real-time processing. Moreover, full encryption’s inflexibility hinders adaptation to diverse data types and access requirements; encrypting everything equally ignores the principle of least privilege and can impede legitimate data operations. Consequently, researchers are actively exploring alternative approaches that balance security with efficiency, seeking methods to encrypt only the most sensitive portions of data or employ encryption schemes that minimize computational overhead without compromising confidentiality.

The landscape of cryptographic security has dramatically shifted, demanding a move beyond historically relied-upon techniques. Early encryption methods largely depended on substitution – replacing characters with others – and permutation – rearranging their order. While once effective, these approaches now prove vulnerable to increasingly sophisticated attacks, including advanced statistical analysis and brute-force methods leveraging immense computational power. Modern adversaries employ techniques like differential cryptanalysis and linear cryptanalysis, exploiting subtle patterns and correlations within the ciphertext to recover the original message. Consequently, current research focuses on algorithms incorporating diffusion and confusion – principles designed to obscure the relationship between the key, plaintext, and ciphertext – alongside more complex mathematical structures to resist these advanced attacks and ensure continued data protection.

Selective encryption, a technique focusing computational resources on the most sensitive data within a larger dataset, presents a compelling alternative to full encryption, but its implementation demands meticulous attention to detail. Rather than protecting every bit of information, this approach encrypts only specific blocks or segments, reducing overhead and boosting efficiency. However, this very selectivity introduces new vulnerabilities; attackers could potentially identify and target unencrypted data, or manipulate the system to reveal the encryption keys used for sensitive portions. Successful deployment requires sophisticated algorithms for determining which data warrants protection, robust key management practices to prevent compromise, and careful consideration of potential side-channel attacks that could exploit patterns in the selective encryption process. Without these safeguards, the benefits of performance gains are easily outweighed by the increased risk of data breaches.

Sudoku’s Deceptive Simplicity: A Novel Scrambling Technique

Sudoku Encryption leverages the computational difficulty associated with the NP-Complete problem, specifically the Sudoku puzzle itself, to provide data scrambling. The core principle rests on the fact that solving a Sudoku puzzle-determining the correct placement of numbers within a grid subject to specific constraints-is known to be an NP-Complete problem. This means there is no known polynomial-time algorithm to solve all instances of Sudoku, and the time required to solve it grows exponentially with the size of the grid. By mapping data elements to Sudoku grid positions and applying transformations based on Sudoku rules, the encryption process introduces a level of complexity that makes brute-force attacks computationally infeasible, effectively scrambling the original data.

Sudoku Transformation within this encryption method operates by partitioning the data into blocks and rearranging these blocks according to a valid Sudoku solution. This process introduces permutation, altering the data’s original order without modifying individual data values. Following the Sudoku Transformation, an XOR Operation is applied across the rearranged data. This XOR operation, using a dynamically generated key, performs diffusion, spreading the influence of each bit of the plaintext across multiple ciphertext bits and obscuring statistical patterns present in the original data. The combination of permutation via Sudoku Transformation and diffusion via XOR Operation provides the foundational cryptographic scrambling of the data.

Timestamp-Based Key Generation creates a unique encryption key for each session by utilizing the system’s current timestamp as a seed value. This timestamp, typically measured in milliseconds or microseconds, is then processed through a cryptographic hash function – such as SHA-256 – to generate a key of a predetermined length. Because the timestamp is constantly changing, the resulting key is statistically unique for each encryption cycle, mitigating the risk of replay attacks and enhancing security. The use of a hash function ensures that even minor variations in the timestamp produce significantly different keys, further strengthening the uniqueness and unpredictability of the encryption process.

Verification and Integrity: The Illusion of Robustness

Padding techniques are integral to accommodating the variable data sizes encountered when applying Sudoku transformations for encryption. Since Sudoku operations require data to conform to a 9×9 grid, input data that does not natively fit this structure must be expanded via padding. This involves appending additional data – often zeros or random values – to the original data stream until its length is a multiple of nine, enabling seamless integration with the Sudoku transformation process. The padding scheme must be reversible to allow accurate decryption and recovery of the original data; therefore, the amount and location of padding must be precisely recorded and applied during both encryption and decryption stages.

Rotation and thresholding are applied as secondary data scrambling techniques following the initial encryption process. Rotation involves circularly shifting pixel values within the image data, disrupting the original pixel arrangement and minimizing correlations. Thresholding introduces non-linearity by replacing pixel values that fall below a predetermined threshold with a new value, further diversifying the encrypted data. The combined effect of these operations increases the complexity of the ciphertext, hindering attempts at cryptanalysis by making it more difficult to identify patterns or relationships between the encrypted and original images and improving resistance to known attacks.

MinHash is employed as a data integrity verification method to confirm the accuracy of the decryption process. This technique functions by generating a compact signature, or hash, of the original data and comparing it to a signature generated from the decrypted data. By calculating the Jaccard index between the MinHash signatures of both datasets, the system determines the similarity between the original and decrypted content. A high Jaccard index value indicates a strong correlation, thereby confirming successful data recovery and validating the integrity of the decryption process against potential alterations or errors. This approach provides a probabilistic guarantee of data matching without requiring a complete byte-by-byte comparison, improving efficiency and scalability.

The security of the proposed encryption system is quantitatively assessed using the Number of Pixel Change Rate (NPCR) and Unified Average Changing Intensity (UACI) metrics. A high NPCR value indicates strong diffusion, meaning a small change in the plaintext results in a significant alteration in the ciphertext. Results demonstrate an achieved NPCR value of approximately 100%, confirming substantial pixel changes following encryption. This high degree of diffusion effectively resists potential statistical attacks aimed at analyzing ciphertext patterns to reveal plaintext information. The UACI metric, used in conjunction with NPCR, further validates the system’s ability to thoroughly alter pixel intensities, enhancing its resistance to cryptanalysis.

Expanding the Framework: A House of Cards

The secure transmission of speech signals demands encryption methods resilient to both intentional attacks and inherent signal distortions. Researchers have demonstrated a highly effective solution by integrating the Threefish cipher – a block cipher known for its speed and security – with Fuzzy C-Means Clustering. This innovative approach first segments the speech signal into distinct clusters based on spectral characteristics, then encrypts each cluster individually using Threefish with dynamically generated keys. The Fuzzy C-Means algorithm allows for graceful handling of variations in speech patterns and background noise, ensuring robust encryption even with imperfect signals. By combining the strengths of both techniques, this method offers a significant advancement in protecting sensitive audio data, providing a high degree of confidentiality and integrity against eavesdropping and unauthorized access.

Die-roll key generation presents a compelling departure from traditional pseudorandom number generators by leveraging the inherent unpredictability of physical dice rolls. This method employs a series of actual die casts, translating each result into a digital value which then forms the encryption key. The system’s security doesn’t rely on complex algorithms, but rather on the difficulty of predicting the outcome of a physical event – each roll is, in essence, a truly random bit source. This approach mitigates vulnerabilities present in software-based generators, which, while statistically random, are ultimately deterministic and potentially crackable given sufficient analysis. The resultant keys, generated through this physical process, are then utilized within the Threefish cipher, offering a heightened level of security particularly against computationally advanced attacks targeting key predictability.

HexE establishes a novel approach to digital media security by adapting the logic of Sudoku puzzles for audio encryption. This method transforms audio data into a grid-like structure, applying Sudoku rules to permute and obscure the original signal. The resulting ciphertext relies on the inherent complexity of solving a Sudoku puzzle – a problem known to be computationally challenging – thus offering a robust layer of protection against unauthorized access. Unlike traditional encryption algorithms, HexE’s security stems from a well-known recreational puzzle, providing a unique and potentially more accessible means of safeguarding sensitive audio content. This innovative application demonstrates the surprising versatility of combinatorial puzzles in the realm of cybersecurity, opening possibilities for novel encryption schemes based on other established problem-solving paradigms.

The foundational principles of this encryption method extend beyond established algorithms, demonstrating adaptability through implementations like Rubik’s Cube Encryption and chaotic systems. Rubik’s Cube Encryption leverages the vast number of possible cube configurations to generate complex keys and diffusion patterns, while the chaotic algorithm utilizes the sensitivity to initial conditions inherent in chaotic dynamical systems to produce unpredictable and secure encryption. These extensions aren’t simply variations; they highlight the core approach’s capacity to integrate diverse computational and mathematical concepts into a robust framework for data security, suggesting potential for further innovation with other complex systems and offering a compelling alternative to traditional cryptographic methods.

The Illusion of Progress: Future Directions and Inevitable Compromise

The Sudoku Encryption framework distinguishes itself through its inherent adaptability, functioning not as a rigid cryptographic solution, but as a versatile platform for integrating emerging techniques. Its core structure, leveraging the rules and constraints of Sudoku puzzles, allows for the seamless substitution of different encryption algorithms within its key generation and data permutation processes. This modularity facilitates experimentation with novel approaches to data security, including post-quantum cryptography and homomorphic encryption schemes, without requiring a complete overhaul of the foundational framework. Consequently, the system can evolve alongside advancements in the field, offering a pathway to maintain robust security even as computational landscapes shift and potential threats become more sophisticated. This flexible architecture positions Sudoku Encryption as a dynamic tool, primed for continuous improvement and tailored to address future cryptographic challenges.

The Sudoku Encryption framework, while demonstrating promise, presents avenues for substantial refinement through puzzle diversification and advanced key generation. Future studies could investigate the integration of logic puzzles beyond Sudoku – such as Kakuro or Hashiwokakero – to increase the complexity and unpredictability of the encryption process. Simultaneously, exploring more sophisticated key generation schemes, potentially incorporating elements of chaos theory or utilizing multiple, interwoven puzzle solutions to derive the final key, could significantly bolster the system’s security. These advancements aim not only to enhance resistance against cryptanalysis but also to create a more adaptable framework capable of evolving alongside emerging computational threats and maintaining a high degree of cryptographic robustness.

The Sudoku Encryption framework’s potential extends significantly with optimization for parallel processing. Currently, the encryption and decryption processes are largely sequential, limiting speed, particularly with large datasets. Implementing parallel algorithms would allow the framework to distribute computational workload across multiple processing cores or even networked systems, dramatically reducing processing time and enhancing scalability. This involves breaking down the encryption/decryption task into smaller, independent sub-tasks that can be executed concurrently. While the core cryptographic principles remain unchanged, leveraging parallel architectures promises to unlock substantial performance gains, making the framework viable for applications requiring real-time encryption of large volumes of data and paving the way for wider adoption in data security solutions.

The long-term viability of the Sudoku Encryption framework hinges on its ability to withstand the looming threat of quantum computing. Current analysis demonstrates a near-perfect Normalized Pixel Change Rate (NPCR) of approximately 100%, indicating substantial ciphertext diffusion. However, the framework’s Unified Average Change Intensity (UACI) – a measure of the magnitude of change in ciphertext – requires further refinement to meet established security standards. Addressing this disparity is critical, as quantum algorithms pose a significant risk to many currently employed encryption methods. Research focused on quantum-resistant adaptations, potentially incorporating post-quantum cryptographic principles, will be essential to ensure the continued effectiveness of Sudoku Encryption in a future defined by quantum computational power and maintain its position as a robust data protection strategy.

The pursuit of elegant encryption, as detailed in this exploration of Sudoku-based algorithms, feels predictably hopeful. It’s a fresh approach to multimedia security, attempting to leverage the computational difficulty of an NP-complete problem. But history suggests this, too, will accrue technical debt. The bug tracker will inevitably fill with edge cases, differential attacks will refine, and what seems robust today will resemble fragile scaffolding tomorrow. As Blaise Pascal observed, “The eloquence of youth is that it knows nothing.” This holds true for security frameworks; the initial promise often overshadows the inevitable compromises production will force upon the system. One doesn’t deploy – one lets go, and prepares for the fallout.

What’s Next?

The pursuit of security through computational complexity is, predictably, a race against diminishing returns. This approach, layering encryption atop the inherent difficulty of solving Sudoku puzzles, feels… familiar. It evokes memories of the last ‘unbreakable’ scheme, and the one before that, all eventually yielding to brute force, side-channel attacks, or simply, a clever enough cryptanalyst. They’ll call it ‘AI-powered puzzle solving’ and raise funding, naturally. The differential attack resistance, while promising, is a snapshot in time; a single discovered weakness will render a significant portion of the effort moot.

Future work will inevitably focus on ‘dynamic Sudoku,’ generating puzzles with varying difficulty on the fly, or perhaps incorporating multiple, interwoven Sudoku grids. This will, of course, increase computational overhead, and the elegant simplicity currently touted will erode into a sprawling codebase maintained by someone who wasn’t there for the original design. It always does. The real challenge isn’t creating more complex encryption; it’s building systems resilient to the inevitable human errors in implementation and key management.

One can envision a shift toward hybrid approaches, combining the puzzle-based encryption with more established cryptographic primitives. This, however, only delays the inevitable. The core problem remains: complexity breeds fragility. What began as a neat algorithm, a digital equivalent of a pen-and-paper puzzle, will eventually become just another layer of tech debt, a testament to the fact that security is not a destination, but an endless, exhausting cycle.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.10119.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Jujutsu Kaisen Modulo Chapter 18 Preview: Rika And Tsurugi’s Full Power

- Upload Labs: Beginner Tips & Tricks

- How to Unlock the Mines in Cookie Run: Kingdom

- ALGS Championship 2026—Teams, Schedule, and Where to Watch

- Top 8 UFC 5 Perks Every Fighter Should Use

- How to Unlock & Visit Town Square in Cookie Run: Kingdom

- Jujutsu: Zero Codes (December 2025)

- USD COP PREDICTION

- Roblox 1 Step = $1 Codes

- Mario’s Voice Actor Debunks ‘Weird Online Narrative’ About Nintendo Directs

2026-01-17 12:14