Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new approach efficiently calculates thousands of eigenpairs for large, non-Hermitian Hamiltonians common in materials science simulations.

This work extends the Chebyshev Accelerated Subspace Eigensolver (ChASE) algorithm, leveraging GPU acceleration and parallel computing for pseudo-hermitian Hamiltonians arising in excitonic and Bethe-Salpeter equation calculations.

Efficiently computing numerous eigenpairs of large, non-normal matrices remains a persistent challenge in computational materials science. This work extends the Chebyshev Accelerated Subspsace Eigensolver for Pseudo-hermitian Hamiltonians (ChASE) to address the spectral problem arising in the treatment of excitonic materials, offering a scalable approach for calculating thousands of eigenpairs. By exploiting the structure of pseudo-hermitian Hamiltonians and introducing an oblique Rayleigh-Ritz projection with quadratic convergence, we achieve performance comparable to the original hermitian solver alongside optimized parallelization for GPU architectures. Will this advancement enable more accurate and efficient modeling of complex optoelectronic phenomena in next-generation materials?

The Challenge of Complex Systems

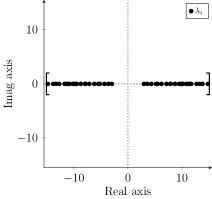

A surprisingly large number of physical systems, ranging from open quantum dots exhibiting radiative decay to resonant optical cavities experiencing energy dissipation, are fundamentally described by non-Hermitian Hamiltonians. This arises because traditional quantum mechanical descriptions, relying on the Hermitian operator assumption, fail to accurately capture processes where energy isn’t conserved – such as when a system interacts with an external environment, losing energy through emission or scattering. While Hermitian Hamiltonians guarantee real energy eigenvalues, non-Hermitian Hamiltonians yield complex eigenvalues, where the imaginary part directly relates to the rate of decay or dissipation. Consequently, computational methods designed for standard quantum problems struggle with the ill-conditioning and unusual properties of non-Hermitian systems, necessitating the development of specialized algorithms to reliably predict their behavior and understand key phenomena like exceptional points and non-reciprocal wave propagation.

Conventional methods for determining the energy levels – or eigenvalues – of a quantum system often falter when applied to non-Hermitian systems, those incorporating decay or dissipation. This difficulty stems from the inherent mathematical properties of non-Hermitian Hamiltonians, which lead to ill-conditioning – meaning even small errors in the input can produce drastically different results. Furthermore, these systems yield complex eigenvalues, requiring specialized algorithms beyond those designed for standard, real-valued energies. Consequently, accurately predicting material properties, such as lifetimes or spectral characteristics, becomes significantly more challenging. The inability to reliably determine these eigenvalues directly impacts the modeling of open quantum systems and limits the precision of simulations in fields like photonics, condensed matter physics, and quantum chemistry.

Determining the eigenvalues of a non-Hermitian Hamiltonian is fundamentally linked to a material’s observable characteristics and future behavior. These eigenvalues don’t simply represent energy levels; they directly correlate to properties like decay rates, lifetimes of excited states, and the stability of a system against perturbations. For instance, in the study of topological materials, the eigenvalues reveal the presence of protected surface states crucial for novel electronic devices. Similarly, understanding the complex eigenvalues in open quantum systems – those interacting with an environment – is essential for predicting how quickly energy dissipates or how efficiently a quantum bit can maintain information. Consequently, advancements in efficiently calculating these eigenvalues aren’t merely computational improvements, but rather a pathway to deeper insights into material science, quantum technology, and a more accurate prediction of dynamic system responses.

ChASE: An Efficient Solver for Complex Systems

ChASE is an iterative eigensolver specifically engineered for calculating the eigenvalues of large, non-Hermitian matrices, a class of problems frequently encountered in various scientific and engineering disciplines. Unlike direct eigensolvers which can be computationally expensive for large matrices, ChASE employs an iterative approach, refining an initial estimate of the eigenvalues through successive approximations. This method is particularly advantageous when only a subset of the eigenvalues are required, or when the matrix size exceeds the capacity of direct methods. The algorithm’s design prioritizes computational efficiency by minimizing the number of matrix-vector multiplications, a key bottleneck in iterative eigensolving, thereby enabling its application to high-dimensional problems.

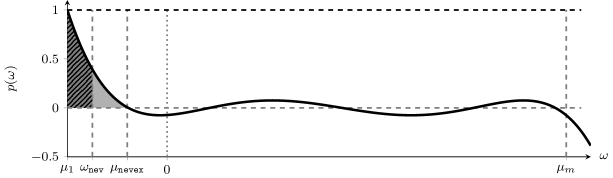

The ChASE eigensolver utilizes a Chebyshev polynomial filter to enhance convergence speed by selectively targeting a defined portion of the matrix’s spectrum. This filter, based on Chebyshev polynomials, effectively attenuates spectral components outside the region of interest – defined by a specified interval [a, b] – while preserving those within it. By focusing computational effort on the relevant spectral subspace, the iterative process converges more rapidly than methods that operate across the entire spectrum, particularly for large, sparse matrices where full spectral decomposition is computationally prohibitive. The order of the Chebyshev polynomial controls the degree of spectral filtering and is selected to balance convergence rate and computational cost.

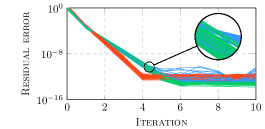

ChASE utilizes the Rayleigh-Ritz procedure in conjunction with its Chebyshev polynomial filter to refine eigenvalue approximations. This method constructs a reduced, Hermitian problem – the hermitian spectral equivalent Rayleigh-Quotient variant – which is then solved to obtain accurate eigenpairs. Empirical results demonstrate that this combination consistently achieves convergence to desired eigenvalues within fewer than 15 iterations, representing a significant improvement in computational efficiency for large, non-Hermitian matrices. The Rayleigh-Ritz procedure effectively extracts the most accurate eigenpairs from the subspace defined by the Chebyshev filter, minimizing residual error with each iteration.

Addressing Non-Orthogonality: A Refined Approach

Standard Ritz variational procedures rely on the assumption that eigenvectors of the Hamiltonian operator are orthogonal. However, non-Hermitian Hamiltonians – those where H \neq H^{\dagger} – frequently produce eigenvectors that do not satisfy this orthogonality condition. This lack of orthogonality introduces inaccuracies when applying the standard Ritz method, as the assumed basis set is no longer mathematically valid for the non-Hermitian system. Specifically, the projection of different eigenvectors onto the trial functions is not zero, leading to incorrect energy estimates and unreliable solutions for the system’s eigenvalues and eigenvectors. Consequently, modifications to the standard Ritz procedure are necessary to accurately treat systems governed by non-Hermitian Hamiltonians.

The Oblique Rayleigh-Ritz procedure addresses the limitations of the standard Rayleigh-Ritz method when applied to systems with non-Hermitian Hamiltonians, which result in non-orthogonal eigenvectors. Instead of relying on the standard eigenvector basis, this procedure introduces a dual basis – a set of vectors that are orthogonal to the eigenvectors of the adjoint operator. This dual basis allows for the proper projection of the trial functions onto the eigenspace, ensuring accurate calculation of energy estimates even when the eigenvectors are not mutually orthogonal. Mathematically, the standard \langle \phi_i | H | \phi_j \rangle overlap integral is replaced with a weighted integral involving the dual basis vectors, effectively accounting for the non-orthogonality and preserving the variational principle.

The ChASE algorithm leverages the Oblique Rayleigh-Ritz procedure to preserve computational accuracy and stability when dealing with non-Hermitian Hamiltonians that produce non-orthogonal eigenvectors. Standard Ritz variational methods rely on the orthogonality of basis functions; however, when eigenvectors are not orthogonal, these methods yield incorrect results. By employing a dual basis, the Oblique Ritz procedure correctly accounts for the non-orthogonality, effectively projecting onto a space spanned by the non-orthogonal eigenvectors and ensuring accurate eigenvalue and eigenvector calculations even with significant deviations from orthogonality. This allows ChASE to maintain reliable performance in systems where non-Hermitian effects are prominent.

Parallelization and the Power of Modern Hardware

ChASE demonstrates a substantial acceleration of complex computations through its design tailored for modern Graphics Processing Units (GPUs). By harnessing the inherent parallelism of GPU architectures, ChASE dramatically reduces execution time compared to traditional CPU-based methods. The system efficiently distributes computational workload across numerous GPU cores, allowing for simultaneous processing of data and minimizing sequential bottlenecks. This optimization is particularly impactful for tasks involving large datasets and intricate algorithms, where the speed gains translate directly into enhanced productivity and the ability to tackle previously intractable problems. The result is a system capable of delivering performance gains that unlock new possibilities in fields such as molecular dynamics, materials science, and artificial intelligence.

ChASE’s performance hinges on efficient inter-GPU communication, and this is achieved through the utilization of the NVIDIA Collective Communications Library (NCCL). NCCL provides highly optimized primitives for collective communication patterns – such as all-reduce, all-gather, and broadcast – which are fundamental to many parallel algorithms. By employing NCCL, ChASE minimizes communication overhead and maximizes bandwidth utilization between GPUs, allowing for faster data exchange and synchronization during computationally intensive tasks. This optimization is particularly crucial when scaling to a large number of GPUs, as communication costs can quickly become a bottleneck; NCCL’s direct GPU-to-GPU communication pathways bypass the host CPU, significantly reducing latency and improving overall application speed.

ChASE demonstrates substantial computational power and scalability on modern GPU systems. Utilizing 256 GPUs, the system consistently achieves approximately 22 PFLOPS/s – a measure of its floating-point operations per second. Importantly, even with a smaller cluster of only 16 GPUs, ChASE attains up to 48.4% of the theoretical peak performance, indicating efficient parallelization and a minimal performance overhead as the system scales. This high level of efficiency suggests that ChASE is well-suited for tackling computationally intensive tasks, delivering significant performance gains with varying levels of hardware resources.

Expanding the Boundaries of Excitonic Modeling

Calculating exciton energies, crucial for understanding the optical properties of materials, relies heavily on solving the complex Bethe-Salpeter Equation HΨ = EΨ. ChASE emerges as a robust and efficient tool specifically designed to tackle this challenge. Unlike some traditional methods, ChASE employs an iterative eigensolver approach that excels in handling the large matrices inherent in these calculations, particularly for extended systems. This capability allows researchers to accurately determine the energies of excitons – bound electron-hole pairs – and predict how materials will absorb and emit light. The solver’s performance isn’t limited to simple cases; it effectively addresses the computational demands associated with modeling the behavior of excitons in technologically relevant materials, paving the way for advancements in fields like photovoltaics and optoelectronics.

Computational studies of excitonic systems often rely on the Bethe-Salpeter Equation (BSE), and the Yambo code is a widely adopted tool for tackling this complex problem. However, solving the BSE requires robust and efficient eigensolvers, and ChASE offers a powerful complementary approach within the Yambo workflow. Rather than replacing existing methodologies, ChASE integrates seamlessly, providing an alternative eigensolver option that can be employed alongside Yambo’s native capabilities. This allows researchers to leverage the strengths of both codes, potentially improving computational performance or tackling larger, more complex systems that would otherwise be inaccessible. The combined approach offers a flexible and versatile platform for investigating the optical properties of materials, furthering understanding of phenomena related to light-matter interactions.

The computational efficiency of ChASE has been rigorously validated through application to excitonic systems, specifically silicon (Si) and molybdenum disulfide (MoS2). Tests demonstrate the code’s ability to handle matrices ranging in size from 23,552 to an impressive 104,000, a scale crucial for accurately modeling the complex electronic interactions within these materials. This performance showcases ChASE’s scalability and confirms its versatility as a tool for investigating a diverse range of technologically relevant semiconductors, extending its applicability beyond smaller, more simplified systems. The successful execution on these sizable matrices suggests ChASE can provide reliable solutions for increasingly complex materials science problems.

The pursuit of computational efficiency, as demonstrated by this extension of the Chebyshev Accelerated Subspace Eigensolver (ChASE), echoes a fundamental principle of clarity through reduction. The algorithm’s focus on extracting thousands of eigenpairs from large, pseudo-hermitian Hamiltonians-critical in materials science applications like solving the Bethe-Salpeter Equation-necessitates a streamlined approach. As Werner Heisenberg observed, “The very act of observing changes that which we observe.” This resonates with the computational challenge; approximations and iterative methods inherently alter the original Hamiltonian, demanding precision and a careful balance between accuracy and computational cost. The ChASE algorithm, through GPU acceleration and optimized parallelization, represents an attempt to minimize this disturbance-to reveal the essential properties of the Hamiltonian with minimal intervention.

What Remains?

The proliferation of parameters in modern materials modeling-a consequence, perhaps, of mistaking detail for understanding-demands ever more efficient eigensolvers. This work addresses that need, but the solution, like all solutions, merely clarifies the shape of the remaining problem. The emphasis on pseudo-hermitian systems, while strategically important for excitonics and beyond, hints at a deeper issue: the persistent tendency to approximate inherently non-hermitian phenomena with methods designed for their hermitian counterparts. Future progress will likely not stem from further algorithmic refinement, but from a willingness to embrace the full complexity of non-hermitian Hamiltonians, even at the cost of analytical tractability.

The demonstrated GPU acceleration, while substantial, feels less like a destination and more like a necessary condition. The true limitation is not computational speed, but the rate at which meaningful problems can be formulated. The ability to compute thousands of eigenpairs is, ultimately, useless without a corresponding ability to interpret them. A focus on automated analysis-algorithms that can discern physical significance from the noise of high-dimensional eigenspaces-represents a more pressing, and arguably more difficult, challenge.

One suspects the ultimate refinement will not be in the solver itself, but in its absence. Perhaps the most fruitful direction lies in developing methods that avoid explicit diagonalization, relying instead on cleverly constructed response functions or correlation matrices that directly yield the desired physical properties. The goal, then, is not to find all the eigenvalues, but to find only the ones that matter, leaving the rest to the elegant indifference of the continuum.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.10557.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Jujutsu Kaisen Modulo Chapter 18 Preview: Rika And Tsurugi’s Full Power

- Upload Labs: Beginner Tips & Tricks

- How to Unlock the Mines in Cookie Run: Kingdom

- ALGS Championship 2026—Teams, Schedule, and Where to Watch

- Top 8 UFC 5 Perks Every Fighter Should Use

- How to Unlock & Visit Town Square in Cookie Run: Kingdom

- Jujutsu: Zero Codes (December 2025)

- Roblox 1 Step = $1 Codes

- USD COP PREDICTION

- Mario’s Voice Actor Debunks ‘Weird Online Narrative’ About Nintendo Directs

2026-01-17 17:08