Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new study explores coding schemes designed to reliably transmit data even when information is inherently repeated and prone to errors.

Researchers present constructions for error-correcting codes optimized for the sum channel, minimizing redundancy while achieving near-optimal single-error correction performance.

Achieving reliable data storage and transmission often demands exceeding inherent channel capacity with redundant information. This paper, ‘Error-Correcting Codes for the Sum Channel’, introduces a novel channel model-the sum channel-and investigates coding schemes designed to minimize redundancy while correcting errors in this system. Specifically, we construct codes that achieve near-optimal performance in correcting both deletion and substitution errors, demonstrating redundancy within a constant factor of optimality for certain error profiles. Could these findings pave the way for more efficient and robust data storage solutions, particularly in emerging fields like DNA-based storage?

The Fragility of Digital Echoes

Despite advancements in digital technology, contemporary data storage and transmission systems exhibit a surprising susceptibility to even minor disruptions – single-bit errors. These seemingly insignificant alterations, where a single binary digit flips from 0 to 1 or vice versa, can accumulate and propagate, corrupting files, compromising calculations, and ultimately undermining the reliability of entire systems. The causes are multifaceted, ranging from cosmic rays and electromagnetic interference to hardware defects and thermal noise. As data storage densities increase and transmission speeds accelerate, the probability of these errors occurring within a given timeframe rises substantially, demanding increasingly sophisticated error detection and correction strategies to maintain data integrity and ensure trustworthy information processing. The pervasiveness of these vulnerabilities highlights a critical, often overlooked, aspect of modern computing infrastructure.

As data storage capacities surge into the exabyte and zettabyte scales, the probability of data corruption rises dramatically, rendering traditional error correction techniques insufficient. Simple redundancy, such as storing multiple copies of data, becomes prohibitively expensive and impractical due to bandwidth and storage limitations. Modern systems now employ sophisticated error-correcting codes – algorithms that add redundant information in a more intelligent way – allowing for the detection and correction of a wider range of errors without requiring excessive overhead. These codes, like Reed-Solomon codes and low-density parity-check (LDPC) codes, introduce complex mathematical relationships within the data, enabling the reconstruction of lost or corrupted information even when faced with significant data loss or noise. The shift towards these advanced mechanisms is not merely about increasing reliability; it’s a fundamental requirement for sustaining the integrity of massive datasets crucial for scientific research, financial transactions, and long-term archival storage.

Data corruption doesn’t always present as a complete loss of information; more often, it subtly alters the data stream through a variety of errors. These alterations commonly take the form of substitutions – where one bit is incorrectly replaced with another – deletions, which remove bits entirely, or insertions, adding extraneous bits into the sequence. Consequently, effective data integrity systems require correction strategies capable of addressing all three error types, rather than relying on simple redundancy. Algorithms must not only detect discrepancies but also pinpoint the precise location and nature of the error to restore the original data with a high degree of confidence, a challenge amplified by the sheer volume and velocity of data in modern systems. This necessitates sophisticated error-correcting codes and protocols designed to handle these varied corruptions and maintain the reliability of stored and transmitted information.

The Sum Channel: A Primitive, Yet Persistent, Architecture

The Sum Channel operates by appending a parity row to a matrix of data elements. This parity row is calculated as the bitwise XOR (exclusive OR) of all elements in each column of the data matrix. Consequently, each element in the parity row represents the parity of its corresponding column. During error detection, the parity row is recalculated from the received data matrix. Any discrepancy between the recalculated parity row and the received parity row indicates the presence of at least one bit error within the corresponding column, providing a basic, column-level error flag. This method does not pinpoint the specific bit in error, only its presence within a column.

RAID5, a widely implemented storage configuration, leverages the parity concept introduced by the Sum Channel to achieve data redundancy without the storage overhead of mirroring. In a RAID5 array, parity information is calculated for blocks of data across multiple drives and distributed amongst them. This distribution ensures that if a single drive fails, the data can be reconstructed from the remaining data blocks and the parity information. The parity is calculated as an XOR operation across the data blocks, meaning any single bit error can be detected and corrected. This differs from mirroring, where entire drives are duplicated, offering higher redundancy but reduced storage efficiency. The Sum Channel’s principle of adding a parity row is therefore a core element in the design and functionality of RAID5 systems, providing a cost-effective method for data protection.

The SumMatrix, generated by adding a parity row or column to a data matrix, facilitates error identification by verifying the consistency of sums across rows or columns. If an error occurs within the data, the sum of the affected row or column will deviate from the expected value, indicating the presence of an error. However, the SumMatrix inherently lacks the ability to pinpoint the location of multiple errors or to correct any errors; it simply flags that an inconsistency exists. While effective at detecting single-bit errors, it cannot distinguish between the multiple error scenarios that would invalidate the parity check and therefore cannot perform error correction.

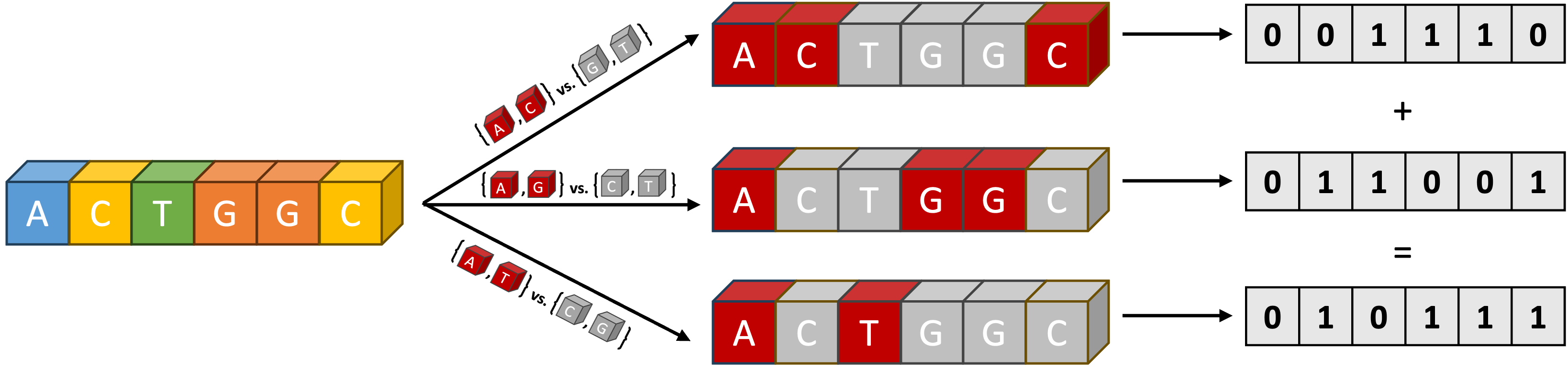

ECCSequencing, a technique used in DNA sequencing and data storage, leverages the principles of the Sum Channel for error detection and correction. This method encodes data into a matrix where each row represents a symbol and a parity row, calculated using a bitwise XOR operation, is added. During data retrieval, the XOR sum of all rows, including the parity row, should equal zero if no errors are present. Any non-zero result indicates an error, and the position of the error can be determined by examining the individual bits within the XOR sum. While basic implementations identify single-bit errors, more complex ECCSequencing schemes utilize multiple parity rows and sophisticated algorithms to correct multiple errors and improve data reliability.

Constructing Resilience: Codes for Reliable Transmission

Hamming codes and Varshamov-Tenengolts codes are error-correcting codes specifically designed to address single-bit errors that can occur during data transmission or storage. Unlike parity checks which only detect errors, these codes utilize redundant bits – extra bits added to the original data – to not only identify the location of a single-bit error but also to reconstruct the original, error-free data. The addition of these redundant bits allows the receiver to differentiate between valid data and data corrupted by a single-bit flip, effectively correcting the error without requiring retransmission. The number of redundant bits is determined by the length of the data being protected, ensuring sufficient capacity to pinpoint and rectify a single-bit error within the data stream.

Error-correcting codes facilitate data reconstruction by introducing redundant bits to the original data stream. These added bits do not represent new information but instead provide parity checks; calculations based on groups of data bits. By analyzing these parity checks, the receiver can identify and correct single-bit errors that may occur during transmission. The number of redundant bits is directly proportional to the desired level of error correction capability; a higher number of redundant bits allows for the detection and correction of more errors, but also increases the overhead of data transmission. The process relies on the principle that errors will alter the results of the parity checks, allowing the receiver to pinpoint the location of the error and restore the original data bit.

The Sphere-Packing Bound represents a fundamental limit on the density of error-correcting codes. It states that for a code with minimum Hamming distance d in a q-ary alphabet, the maximum number of codewords N in a code of length n is bounded by N \le \frac{q^n}{\sum_{i=0}^{t} \binom{n}{i}(q-1)^i}, where t = \lfloor \frac{d-1}{2} \rfloor. This bound arises from considering spheres of radius t around each codeword; these spheres must not overlap to allow for correct decoding, and the volume of these spheres constrains the total number of codewords that can be packed into the n-dimensional space. Consequently, the Sphere-Packing Bound dictates a trade-off between the code’s ability to correct errors (determined by the minimum distance d) and its efficiency (quantified by the code size N) for a given block length n.

Tensor Product Codes represent an advancement beyond single-bit error correction codes like Hamming and Varshamov-Tenengolts, designed to function effectively in more complex error scenarios. Research has focused on minimizing the redundancy inherent in these codes; our work establishes bounds demonstrating a construction achieving a redundancy of ⌈log₂(ℓ+1)⌉. This represents a significant improvement, falling within a single bit of the theoretical lower bound of 2^(nℓ)/(ℓ+1), where ℓ defines the error correction capability and n is the block length of the code.

The Cascade of Corruption: Beyond Isolated Errors

Traditional error correction often focuses on mitigating the impact of single-bit alterations, but real-world data transmission and storage are susceptible to more complex disturbances. Beyond simple flips, data can suffer from deletions – the complete loss of bits – and insertions, where extraneous bits appear. These phenomena pose a significant challenge to data integrity, as standard correction codes designed for single errors are ineffective against them. Consequently, robust data management requires codes capable of addressing these varied forms of corruption simultaneously; a system that only accounts for substitutions would be easily compromised by even a single deletion or insertion. The ability to reliably reconstruct data in the face of these combined threats is paramount for ensuring the dependability of modern digital systems.

Data corruption rarely manifests as isolated events; a seemingly simple substitution error can cascade into more complex issues like deletions or insertions. This interconnectedness stems from how digital information is encoded and transmitted, where a slight disturbance can disrupt the intended sequence. Consequently, error correction strategies must move beyond addressing single-bit flips in isolation and embrace versatile approaches capable of handling these dependent error types. Ignoring these relationships risks a system’s inability to accurately reconstruct data when faced with realistic corruption scenarios, necessitating codes designed to anticipate and mitigate the potential for a single error to trigger a chain reaction of further inaccuracies. Effective data management, therefore, relies on acknowledging this complexity and building resilience against the full spectrum of possible corruptions.

The ConfusabilityGraph offers a compelling visualization of the challenges inherent in error correction, demonstrating how easily a received signal can be misinterpreted. This graph doesn’t simply depict error rates, but rather the inherent ambiguity where a single corrupted data point could realistically decode into multiple valid possibilities. It illustrates that the distinction between different error types – substitutions, deletions, and insertions – isn’t always clear-cut; a minor alteration can cascade into a more significant distortion, and the decoder faces a landscape of plausible, yet incorrect, interpretations. By mapping these confusable states, the graph emphasizes the need for error-correcting codes to go beyond simply detecting errors, and instead actively disambiguate them, choosing the most likely original message from a field of potential reconstructions.

Recognizing the interconnectedness of data corruption – where a simple substitution error can cascade into deletions or insertions – allows for the development of remarkably robust data management systems. This understanding moves beyond addressing errors in isolation and enables the creation of error-correcting codes designed to anticipate and mitigate complex failures. Recent constructions, specifically for the case of ℓ=2, demonstrate a significant advancement in this field by achieving optimal redundancy – meaning the system uses the minimal necessary overhead to guarantee reliable data recovery. This level of efficiency is crucial for applications ranging from long-term data storage to real-time communication, ensuring data integrity even in challenging environments.

The pursuit of minimizing redundancy in the sum channel, as detailed in this work, echoes a fundamental truth about complex systems. A system striving for absolute error-free transmission is, in effect, a static entity, incapable of adaptation. As Grace Hopper observed, “It’s easier to ask forgiveness than it is to get permission.” This isn’t simply a statement about bureaucratic efficiency, but a recognition that rigid perfection leaves no space for evolution. The inherent redundancy explored here, while seemingly counterintuitive, is not a flaw, but the very mechanism by which the system tolerates, and even expects, imperfection. A system that never ‘breaks’ is, ultimately, a system that never grows.

The Turning of the Wheel

This work, concerning the sum channel and the minimization of redundancy, arrives at a familiar juncture. Every dependency is a promise made to the past, and here, that promise is one of efficient correction. Yet, the pursuit of ‘optimal’ is often a mirage. The sum channel, by its nature, invites a certain level of self-correction, a whisper of inherent resilience. The challenge, then, isn’t merely minimizing added redundancy, but understanding where the channel already offers succor. It is a question of coaxing forth existing structure, not imposing new ones.

The constructions presented are a refinement, certainly, but they highlight a deeper truth: control is an illusion that demands SLAs. Future work will inevitably focus on more complex error models – the channel rarely confines itself to single events. But the real leap may lie in abandoning the notion of correcting errors, and embracing a system that anticipates, accommodates, and even learns from them.

Everything built will one day start fixing itself. The study of error-correcting codes, in the long arc, isn’t about achieving perfect transmission; it’s about designing systems that gracefully degrade, that find equilibrium within noise. The wheel turns, and the patterns of failure, when observed with sufficient patience, reveal the seeds of future stability.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.10256.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Jujutsu Kaisen Modulo Chapter 18 Preview: Rika And Tsurugi’s Full Power

- How to Unlock the Mines in Cookie Run: Kingdom

- ALGS Championship 2026—Teams, Schedule, and Where to Watch

- Upload Labs: Beginner Tips & Tricks

- Top 8 UFC 5 Perks Every Fighter Should Use

- Jujutsu: Zero Codes (December 2025)

- How to Unlock & Visit Town Square in Cookie Run: Kingdom

- Roblox 1 Step = $1 Codes

- Mario’s Voice Actor Debunks ‘Weird Online Narrative’ About Nintendo Directs

- The Winter Floating Festival Event Puzzles In DDV

2026-01-18 15:08