Author: Denis Avetisyan

As DNA emerges as a promising medium for long-term data archiving, new coding schemes are vital to overcome the challenges of fragment reassembly and data corruption.

This review explores coding strategies – including locality-sensitive hashing and error-correcting codes – designed for reliable data storage and recovery in the noisy torn paper channel model.

Archival DNA data storage offers immense potential but faces significant challenges from strand decay and fragmentation. This is addressed in ‘Coding Schemes for the Noisy Torn Paper Channel’, which investigates robust coding strategies for reconstructing data from noisy, unordered fragments-modeling DNA degradation as a probabilistic ‘torn paper’ channel. The paper devises and compares index-based and data-dependent (locality-sensitive hashing) coding schemes, achieving reconstruction rates exceeding 99% with no false positives. Can these techniques be further refined to overcome computational limitations and enable practical, large-scale DNA archival systems?

The Inherent Fragility of Digital Archives

Contemporary digital data storage, while ubiquitous, is fundamentally constrained by its physical underpinnings. Traditional methods-hard drives, solid-state drives, and even optical media-rely on maintaining distinct physical states to represent information, states which inevitably degrade over time. This presents a significant challenge for archival data, information intended to be preserved for decades or even centuries. The relentless pursuit of increased storage density, cramming ever more bits into a given space, exacerbates this problem; smaller physical distinctions become more susceptible to noise, interference, and ultimately, data loss. Furthermore, the rapid pace of technological advancement renders storage media obsolete, requiring costly and complex data migration before information is lost not to physical decay, but to incompatibility. Consequently, the long-term preservation of digital heritage-scientific datasets, historical records, cultural artifacts-demands exploration of fundamentally new storage paradigms.

Despite the limitations of contemporary digital storage, deoxyribonucleic acid presents a compelling path forward for long-term data archiving. The molecule boasts an extraordinary storage density – theoretically capable of housing all the world’s data within a space the size of a shoebox – and, under ideal conditions, exhibits remarkable stability potentially lasting millennia. However, this promise is tempered by DNA’s inherent susceptibility to degradation. Environmental factors, such as oxidation, hydrolysis, and radiation, induce chemical alterations and fragmentation of the DNA strands, leading to data loss. These decay processes aren’t uniform; rather, they manifest as localized damage, creating errors within the stored information. Consequently, researchers are actively investigating the specific mechanisms driving DNA decay, aiming to develop error-correction strategies and protective measures to ensure the integrity of data preserved within this biological medium.

The long-term viability of DNA as a data storage medium hinges on a comprehensive understanding of its degradation pathways. While remarkably stable compared to conventional digital formats, DNA is not impervious to damage from environmental factors like oxidation, hydrolysis, and radiation. These processes lead to chemical modifications and physical breaks in the DNA strands, ultimately corrupting the encoded information. Researchers are actively investigating the specific mechanisms of these degradative processes – pinpointing the types of damage that occur, their rates under various conditions, and the resulting impact on data retrieval. This knowledge is essential for designing robust storage systems that incorporate error correction codes, protective encapsulation strategies, and methods for detecting and repairing damaged DNA, ensuring that valuable data remains accessible for centuries, if not millennia.

Researchers increasingly utilize the ‘Torn Paper Channel’ (TPC) as a powerful computational model to investigate the challenges inherent in long-term DNA data storage. This model, inspired by the physical fragmentation of paper documents, simulates the processes of DNA degradation – including breakage, modification, and loss of information – that occur over time. By virtually ‘tearing’ digital data encoded in DNA sequences, the TPC allows scientists to predict and mitigate potential errors arising from DNA fragmentation, enabling the development of sophisticated error-correction codes and robust data retrieval strategies. Importantly, the TPC isn’t limited to simulating random damage; it can also model site-specific degradation, offering insights into how environmental factors and enzymatic activity impact data integrity. This predictive capability is crucial for designing DNA archival systems capable of preserving information for centuries, or even millennia, by anticipating and addressing the inevitable ‘tears’ in the molecular fabric of stored data.

Reconstructing the Past: Fragment Reconstruction Strategies

Conventional error-correcting codes are designed for sequential data streams and perform poorly when applied to fragmented DNA. DNA decay typically results in the random breakage of the molecule into numerous unordered fragments. Traditional coding schemes rely on knowing the position of errors within a defined sequence; however, the lack of inherent order in fragmented DNA means positional information is lost, rendering standard error correction ineffective. These schemes assume a contiguous data stream, and cannot reliably reconstruct data when fragment order is unknown, as the algorithms cannot determine the correct sequence for error detection and correction. This presents a significant challenge for data retrieval from degraded samples.

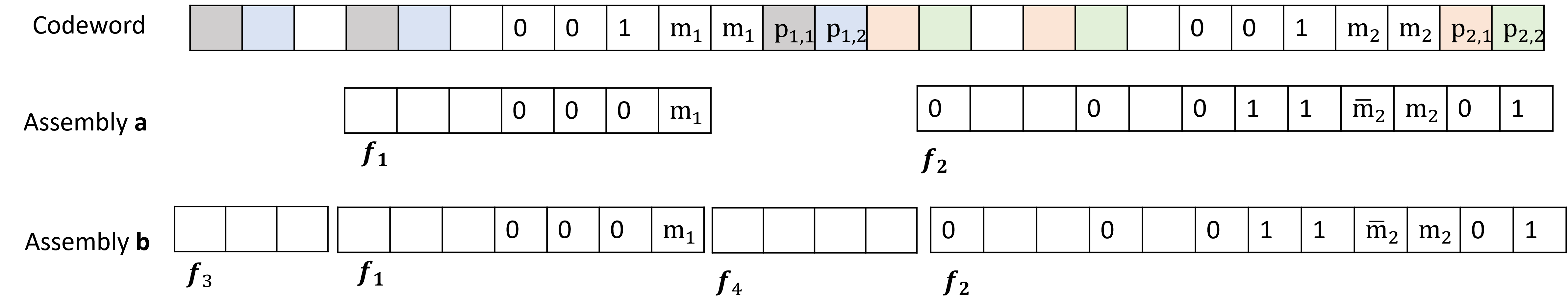

Marker-Based Codes and the Interleaving Pilot Scheme address data reconstruction challenges by incorporating specifically designed sequences – Markers – into the original data stream. These Markers serve as delimiters, clearly identifying the boundaries of individual data fragments after decay and fragmentation. Complementing Markers are Indices, often generated using techniques like De Bruijn Sequences, which assign a unique positional identifier to each fragment. This allows algorithms to not only detect fragment boundaries via Markers, but also to determine the original sequential order based on the Index values, facilitating accurate reassembly of the complete data set even with significant fragmentation and data loss.

Data reconstruction from highly fragmented DNA relies on the implementation of ‘Indices’, often facilitated by techniques such as De Bruijn sequences. A De Bruijn sequence of order k contains every possible subsequence of length k exactly once. By representing DNA fragments as subsequences and utilizing a De Bruijn graph, the original sequence can be reassembled even with significant fragmentation. Each fragment serves as a node, and edges connect overlapping fragments, allowing algorithms to traverse the graph and reconstruct the complete sequence. The efficiency of this method stems from its ability to uniquely identify fragment relationships, minimizing ambiguity and enabling accurate reconstruction despite substantial data loss or disordering.

Fragment reconstruction methods, utilizing techniques like marker-based coding and interleaving pilot schemes, address data loss inherent in DNA decay by introducing redundancy and positional information. These approaches don’t eliminate errors entirely, but establish a framework for error correction and data retrieval even with significant fragmentation. The core principle involves encoding data with identifiable markers and indices, allowing algorithms to computationally reassemble the original sequence. This is achieved by leveraging the known characteristics of the encoding scheme to statistically determine the most probable original order of fragments, effectively mitigating the impact of random data loss and facilitating the recovery of a substantial portion of the initial data set.

Optimizing Resilience: Code Robustness and Efficiency

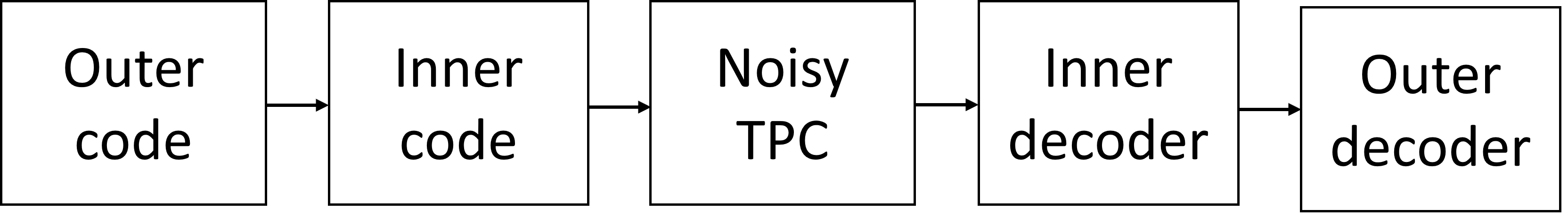

Nested codes build upon the principles of Index-Free Codes by implementing a hierarchical error correction strategy. This approach involves encoding data with multiple layers of redundancy, where each layer addresses potential errors that may have bypassed previous layers. Specifically, an outer code protects against larger-scale failures, while inner codes address localized errors. This multi-layered protection significantly enhances robustness compared to single-layer coding schemes, increasing the probability of successful data recovery even under substantial data degradation or loss. The hierarchical structure allows for targeted error correction at different levels of granularity, optimizing the efficiency of the reconstruction process and improving overall system reliability.

The Hash-Based Approach to data fragment identification and integrity verification utilizes data-dependent hash values calculated from the content of each fragment. This method avoids the need for explicit positional metadata by deriving fragment locations from the hash values themselves. Specifically, the hash function maps fragment content to a unique identifier, enabling reconstruction algorithms to determine the correct order and detect any missing or corrupted fragments. Data dependency ensures that even minor alterations to a fragment will result in a significantly different hash value, providing a robust mechanism for error detection. This approach offers an alternative to index-based methods, particularly beneficial in scenarios where maintaining positional information is impractical or unreliable.

Combined implementation of nested codes, hash-based approaches, and the Noisy TPC model yields a data reconstruction probability exceeding 99% across a defined parameter space. Specifically, this performance is maintained with breakage parameters (α) of 0.05, 0.07, and 0.10, representing the proportion of data fragments lost. Furthermore, reconstruction accuracy remains above 99% even with nucleotide substitution probabilities (ps) ranging from 0.4% to 5%, simulating errors introduced during data storage or transmission. These results demonstrate the robustness of the combined method under varying data degradation conditions.

The ‘Noisy TPC’ model simulates data degradation common in long-term storage systems, specifically focusing on both fragment loss and substitution errors. This model introduces decay parameters representing the probability of fragment unavailability and substitution probabilities to quantify the likelihood of incorrect data being read. Testing with this model demonstrates that the combined use of Nested Codes, Index-Free Codes, and the Hash-Based Approach achieves a reconstruction probability exceeding 99% across a range of breakage parameters α ∈ \{0.05, 0.07, 0.10\} and substitution probabilities p_s ∈ \{0.4\%, 0.9\%, 1.8\%, 5\%\} . The high reconstruction rate under these conditions validates the effectiveness of the combined methodology in mitigating the effects of realistic data corruption and loss scenarios.

The pursuit of robust data storage, as detailed in this work concerning the Torn Paper Channel, necessitates a reduction of complexity. The core challenge-reliable fragment reassembly amidst noise-demands elegant solutions, not convoluted ones. It recalls the sentiment of Henri Poincaré: “It is through science that we arrive at truth, but it is simplicity that makes us understand it.” This principle directly informs the design of efficient coding schemes; the paper’s exploration of both index-based and locality-sensitive hashing approaches strives for precisely this – minimal viable complexity to maximize data recovery. Clarity is the minimum viable kindness, especially when dealing with the inherent fragility of information storage.

What Remains?

The pursuit of data storage within the molecular realm inevitably distills to a question of fragmentation and retrieval. This work, by addressing coding schemes for the ‘torn paper channel’, does not so much solve the problem of DNA storage as it clarifies the essential constraints. The efficacy of any approach hinges not on complexity of code, but on the minimization of ambiguity in reassembly. Index-based and locality-sensitive hashing methods offer paths, but each introduces its own overhead – a trade between coding rate and computational burden. The true measure of progress will not be bits stored, but bits reliably retrieved.

Future efforts should resist the temptation to layer sophistication upon sophistication. The challenge is not to anticipate every possible degradation, but to design systems robust to any degradation. A fruitful avenue lies in further exploration of codes that inherently prioritize local fragment reassembly, effectively limiting the scope of error propagation. The ideal code, perhaps, is the one that requires the least – the simplest scheme that meets the fundamental demands of reliable retrieval.

Ultimately, the limitations are not technical, but physical. The channel – DNA itself – dictates the ultimate capacity. The art, then, is not to force more information through a narrow passage, but to accept what can be reliably conveyed. The remaining signal, stripped of artifice, is all that truly matters.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.11501.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Jujutsu Kaisen Modulo Chapter 18 Preview: Rika And Tsurugi’s Full Power

- How to Unlock the Mines in Cookie Run: Kingdom

- ALGS Championship 2026—Teams, Schedule, and Where to Watch

- Assassin’s Creed Black Flag Remake: What Happens in Mary Read’s Cut Content

- Upload Labs: Beginner Tips & Tricks

- Jujutsu: Zero Codes (December 2025)

- Mario’s Voice Actor Debunks ‘Weird Online Narrative’ About Nintendo Directs

- Top 8 UFC 5 Perks Every Fighter Should Use

- One Piece: Is Dragon’s Epic Showdown with Garling Finally Confirmed?

- Gold Rate Forecast

2026-01-19 12:45