Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have developed a comprehensive framework to rigorously evaluate the effectiveness of firmware fuzzers, tackling critical challenges in embedded system security.

FirmReBugger provides a standardized, automated approach to benchmarking monolithic firmware fuzzers, addressing issues like realistic bug sets, DMA handling, and false positive reduction.

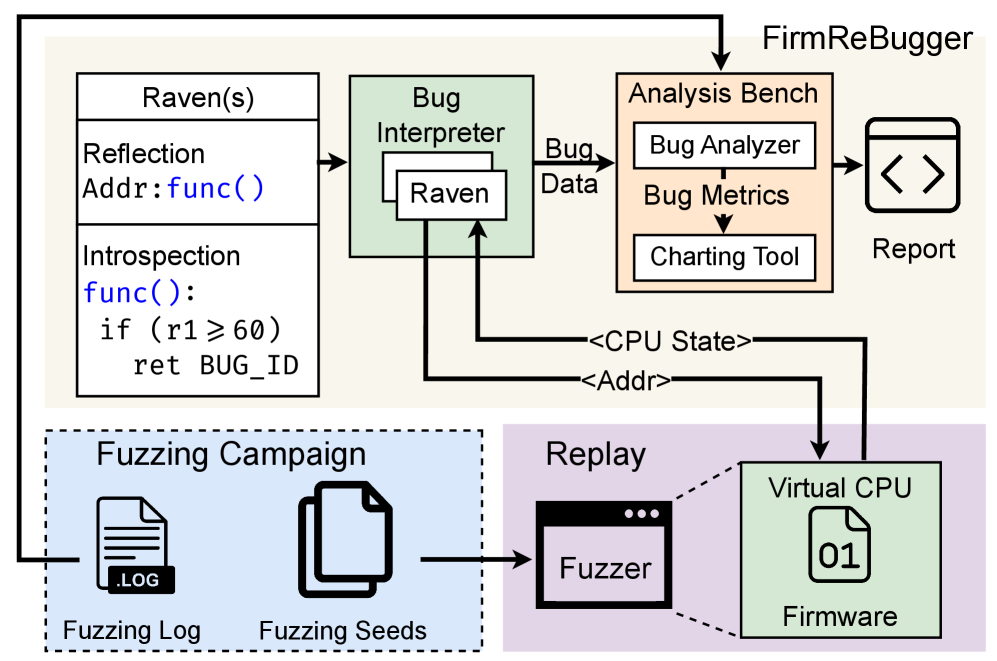

Despite increasing attention to firmware security, evaluating progress in monolithic firmware fuzzing remains challenging due to a lack of reliable, bug-based benchmarks. To address this, we introduce ‘FirmReBugger: A Benchmark Framework for Monolithic Firmware Fuzzers’, a holistic framework for fairly assessing fuzzers with a realistic and diverse benchmark, FirmBench, comprised of 313 software bug oracles. FirmReBugger automates bug analysis using bug oracles-interpretable expressions of bug descriptors-allowing for accurate reporting of detected bugs and isolating benchmark implementation from fuzzer modifications. Will this framework enable more rapid and reproducible advances in discovering critical vulnerabilities within the complex landscape of monolithic firmware?

Unmasking the Firmware Fuzzing Bottleneck

Conventional fuzzing methodologies, while effective against many software targets, often encounter significant limitations when applied to monolithic firmware images. These systems, unlike discrete applications, present a vastly expanded attack surface due to the integration of numerous complex peripherals and intricate device driver interactions. The sheer size of the firmware, coupled with the difficulty in achieving sufficient code coverage, frequently results in low bug detection rates; a substantial portion of the code remains untested despite prolonged fuzzing campaigns. This is further compounded by the fact that many firmware bugs manifest only under specific, often rare, execution conditions, requiring a level of input space exploration that traditional fuzzers struggle to achieve efficiently. Consequently, a considerable amount of effort can be expended with minimal return, highlighting the need for specialized techniques tailored to the unique characteristics of embedded systems.

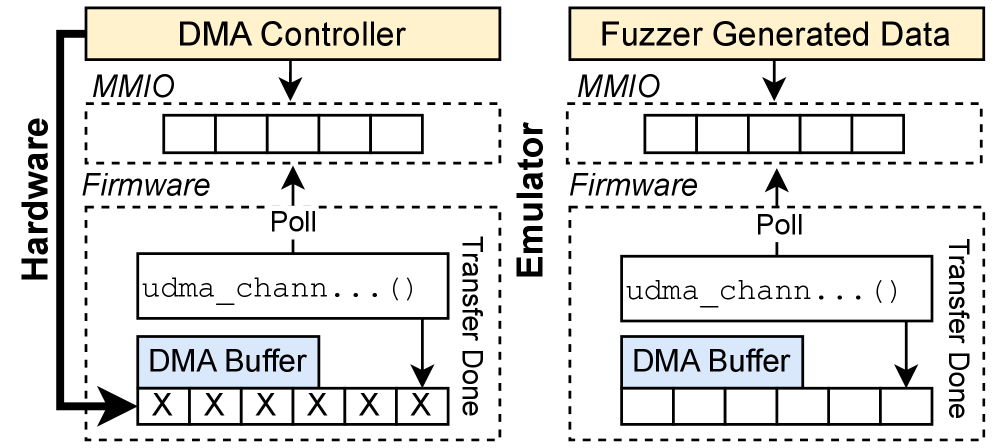

Firmware security testing faces unique obstacles due to the intricate nature of embedded systems. Complex peripherals, such as custom communication interfaces or specialized sensors, introduce a vast array of potential failure points that traditional fuzzing struggles to adequately probe. Furthermore, Direct Memory Access (DMA) interactions, where peripherals directly manipulate memory without CPU intervention, create hidden data dependencies and timing vulnerabilities difficult to detect through conventional input analysis. Compounding these issues, many firmware designs intentionally incorporate delays – for power management or system stabilization – which significantly slow down the fuzzing process and limit the exploration of the input space, as the system spends more time waiting than actively processing potentially malicious data. These combined factors create a substantial bottleneck, hindering effective bug discovery and leaving firmware vulnerable to exploitation.

Input bloating presents a significant impediment to effective firmware fuzzing, as the process inherently involves the accumulation of test cases derived from mutated inputs. This exponential growth of data isn’t merely a storage concern; it dramatically slows down execution speed. Each new input must be processed, potentially triggering complex state changes within the firmware, and the sheer volume of data overwhelms the system’s ability to efficiently explore the input space. Consequently, the time required to achieve meaningful code coverage increases substantially, diminishing the overall fuzzing efficiency and the likelihood of discovering critical vulnerabilities before deployment. The problem is compounded by the fact that many firmware systems have limited resources, making them particularly susceptible to performance degradation from excessive data handling.

Addressing the limitations of current firmware fuzzing necessitates a shift toward techniques capable of handling the intricacies of embedded systems. The demand isn’t simply for increased computational power, but for methodologies that intelligently navigate complex peripheral interactions and mitigate the effects of deliberately introduced delays. Scalability is paramount; existing approaches often falter as the volume of test data grows, requiring innovative strategies to manage ‘input bloating’ and maintain efficient exploration of the firmware’s attack surface. Ultimately, a more robust and adaptable toolkit is vital to proactively identify vulnerabilities and strengthen the security posture of an increasingly interconnected world reliant on embedded devices.

Introducing FirmReBugger: A Targeted Vulnerability Benchmark

FirmReBugger is a benchmark designed to assess the effectiveness of fuzzing tools when applied to monolithic firmware images. Unlike benchmarks relying on code coverage or crash counts, FirmReBugger utilizes a collection of real-world firmware binaries containing deliberately introduced and documented bugs. This bug-based approach enables a more precise evaluation of a fuzzer’s ability to identify and trigger specific vulnerabilities within a complex, self-contained system. The benchmark’s design prioritizes evaluating fuzzing techniques on complete firmware images, reflecting the challenges and complexities of testing embedded systems as deployed, rather than isolated components.

FirmReBugger employs a curated suite of firmware images, each containing deliberately introduced and documented bugs. This approach facilitates reproducible security evaluations by providing a consistent and known set of vulnerabilities for testing. The use of pre-bugged firmware enables standardized comparisons of fuzzing techniques; researchers can objectively measure a fuzzer’s ability to detect these known issues across different configurations and algorithms. This methodology moves beyond relying on random crash reports and allows for quantitative assessment of fuzzer performance, providing a more reliable metric than simply measuring crashes per second.

FirmReBugger incorporates automated triaging to significantly reduce the manual effort associated with bug identification within firmware binaries. This process involves automatically analyzing crash reports generated during fuzzing and filtering out duplicates, irrelevant crashes, and those lacking sufficient information for effective investigation. The automated system prioritizes likely vulnerabilities based on factors such as crash location, code coverage, and the presence of exploitable patterns. This prioritization allows researchers to focus on high-impact bugs, improving efficiency and accelerating the firmware security assessment process. The automated triage system also includes functionalities for clustering similar crashes, facilitating a more systematic and comprehensive analysis of the identified issues.

FirmReBugger employs ‘Raven’ bug descriptors, a structured methodology for defining vulnerability characteristics, to enhance the accuracy of fuzzer evaluations. These descriptors precisely specify the necessary preconditions for triggering a bug, including required inputs, system states, and execution paths leading to the vulnerability. By detailing these conditions, Raven descriptors move beyond simple crash reporting and enable precise bug reproduction and verification. This granular approach facilitates automated assessment of fuzzer effectiveness, allowing for quantifiable comparisons based on a fuzzer’s ability to satisfy the specified conditions and reach the identified vulnerabilities, rather than relying on potentially ambiguous crash reports.

Validating Fuzzers with FirmReBugger: An Empirical Assessment

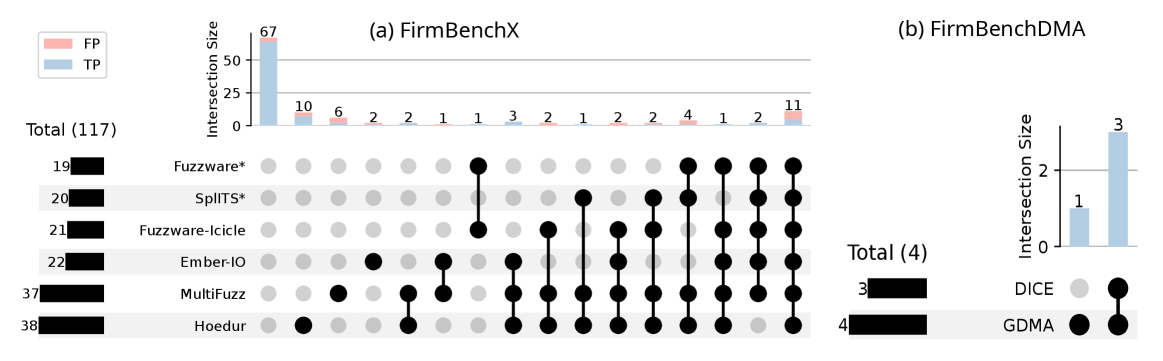

FirmReBugger’s evaluation capabilities extend to a broad range of firmware vulnerabilities, with specific attention paid to Direct Memory Access (DMA) interactions. The ‘FirmBenchDMA’ subset of the benchmark is specifically designed to assess fuzzer performance when encountering challenges related to DMA, which often represent critical security surface areas in embedded systems. This subset includes firmware images intentionally crafted to exhibit DMA-related flaws, allowing researchers to quantitatively measure a fuzzer’s ability to detect and exploit these types of vulnerabilities. The inclusion of DMA-focused challenges provides a more comprehensive assessment than benchmarks relying solely on CPU-level code execution.

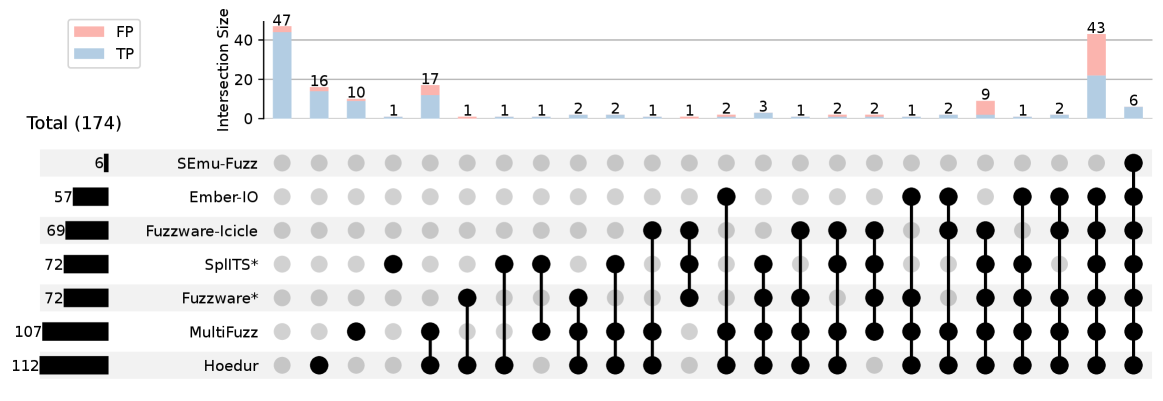

FirmReBugger has been utilized to assess the capabilities of nine leading fuzzing tools, enabling a standardized performance comparison. This evaluation framework provides a consistent methodology for benchmarking fuzzers against a common set of firmware challenges, allowing researchers to objectively measure their effectiveness in discovering vulnerabilities. The resulting data facilitates a direct comparison of state-of-the-art tools, highlighting their respective strengths and weaknesses in firmware security testing. The benchmark’s design ensures a level playing field, enabling meaningful insights into fuzzer performance beyond simple bug counts.

FirmBenchX constitutes a portion of the FirmReBugger benchmark suite and is specifically designed to assess fuzzer performance against realistic, unmodified firmware images. This subset utilizes binaries that have not been intentionally weakened or modified to introduce vulnerabilities, thereby evaluating a fuzzer’s ability to discover bugs stemming from inherent complexities and potential weaknesses already present in typical embedded systems. The inclusion of FirmBenchX provides a measure of a fuzzer’s robustness and resilience when faced with challenges that are not artificially introduced for testing purposes, offering a more practical assessment of its real-world effectiveness.

FirmReBugger enables detailed fuzzer performance analysis by targeting known firmware vulnerabilities, specifically those related to complex peripheral interactions and the presence of magic values. The benchmark suite consists of three distinct sets – FirmBench, FirmBenchDMA, and FirmBenchX – collectively comprising a total of 295 identified bugs. This granular approach allows researchers to move beyond overall fuzzer effectiveness and pinpoint specific strengths and weaknesses in handling particular firmware challenges, providing a more nuanced comparative evaluation of state-of-the-art fuzzing tools.

Deconstructing False Positives and Charting Future Directions

Fuzzing, while a powerful technique for discovering software vulnerabilities, frequently encounters the challenge of ‘false positives’ – instances where a program crash is flagged but doesn’t actually indicate a security flaw. These misleading signals arise from several sources, notably inaccuracies within the emulation environment used to test the firmware. Emulation, the process of mimicking a system’s behavior, isn’t perfect; simplifications and imperfect modeling of hardware interactions can lead to crashes that wouldn’t occur on a real device. Similarly, edge cases – unusual or rarely encountered input combinations – can trigger errors in the emulation that don’t reflect genuine vulnerabilities in the firmware itself. Identifying and filtering these false positives is therefore crucial for efficient vulnerability research, preventing security analysts from wasting time investigating non-issues and allowing them to focus on genuine threats.

Automated triaging is essential in modern fuzzing, as the process frequently generates numerous ‘false positives’ – reported crashes that don’t represent genuine security vulnerabilities. FirmReBugger addresses this challenge with an integrated system that automatically filters out these non-critical crashes, significantly reducing the workload for security analysts. This automated process examines crash reports, categorizing them based on severity and potential impact, effectively prioritizing legitimate bugs for investigation. By distinguishing between superficial errors and actionable vulnerabilities, the triaging system not only improves efficiency but also enhances the overall effectiveness of the fuzzing campaign, allowing researchers to focus their efforts on the most critical issues and maximizing the return on investment of their time and resources.

Continued advancements in automated vulnerability discovery rely heavily on minimizing the impact of false positives, necessitating focused research into both improved bug characterization and enhanced emulation precision. More nuanced bug descriptors, moving beyond simple crash signatures, could allow for more intelligent filtering and prioritization of potential vulnerabilities. Simultaneously, refining the accuracy of emulation environments – addressing discrepancies between simulated and real-world firmware behavior – promises to reduce the occurrence of crashes triggered by emulation artifacts rather than genuine flaws. This dual approach – sophisticated analysis coupled with realistic simulation – will not only streamline the vulnerability discovery process but also increase confidence in the identified bugs, ultimately leading to more secure embedded systems.

The deployment of FirmReBugger successfully uncovered 181 distinct bugs within the target firmware, validating its efficacy as a fuzzing tool. Importantly, identified false positives – crashes that didn’t represent genuine vulnerabilities – were not discarded. Instead, these instances were meticulously retained and analyzed, providing valuable data regarding the fuzzer’s exploration strategies and the depth of its testing. This approach allowed researchers to gain insights into the causes of inaccurate reporting, ultimately informing improvements to the emulation process and bug descriptor refinement, and creating a feedback loop for optimizing future fuzzing campaigns.

![Fuzzware[44] covered significantly fewer blocks in the patched Thermostat binary compared to the vulnerable version across multiple fuzzing trials, indicating successful bug mitigation, as highlighted by the mean time to trigger the bug denoted by a star.](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.15774v1/x2.png)

The pursuit of robust firmware security, as detailed in this framework, isn’t merely about confirming expected behavior, but actively probing for deviations. It echoes Carl Friedrich Gauss’s sentiment: “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” FirmReBugger, in a way, builds upon existing fuzzing techniques, leveraging their strengths while systematically dissecting weaknesses. The framework’s focus on realistic bug sets and addressing the complexities of DMA isn’t about validating a system’s perfection, but identifying the points of failure-the ‘giants’ upon which future improvements stand. One pauses and asks: what if the reported false positives aren’t errors, but signals of unexplored code paths, opportunities for deeper understanding?

What’s Next?

The construction of FirmReBugger, while a step toward systematizing the art of firmware breakage, inevitably reveals just how much remains delightfully chaotic. The framework neatly packages bug discovery, yet the very act of defining a ‘realistic’ bug set feels… provisional. One suspects the most interesting flaws aren’t the ones easily categorized, but the emergent behaviors born from the complex interplay of poorly-documented peripherals. DMA, in particular, appears less a feature and more a convenient avenue for controlled demolition-future work might explore intentionally amplifying these vulnerabilities to observe systemic failure modes.

The mitigation of false positives, addressed within, feels less like a solution and more like a temporary truce. The ‘oracle problem’ isn’t about perfecting detection; it’s about accepting that any system built on approximation will inevitably declare harmless noise a critical error. Perhaps the true benchmark isn’t code coverage, but the rate at which a fuzzer can confidently incorrectly identify a vulnerability-a measure of its audacity, if you will.

Ultimately, FirmReBugger provides a controlled environment for dismantling firmware. The real challenge lies in embracing the inevitable mess. Future iterations shouldn’t strive for increased precision, but for a richer, more nuanced understanding of how things fall apart. After all, reverse-engineering reality requires a willingness to take things-and systems-utterly to pieces.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.15774.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- How to Unlock the Mines in Cookie Run: Kingdom

- Assassin’s Creed Black Flag Remake: What Happens in Mary Read’s Cut Content

- Jujutsu Kaisen: Divine General Mahoraga Vs Dabura, Explained

- The Winter Floating Festival Event Puzzles In DDV

- Upload Labs: Beginner Tips & Tricks

- Top 8 UFC 5 Perks Every Fighter Should Use

- Jujutsu: Zero Codes (December 2025)

- MIO: Memories In Orbit Interactive Map

- Xbox Game Pass Officially Adds Its 6th and 7th Titles of January 2026

- Where to Find Prescription in Where Winds Meet (Raw Leaf Porridge Quest)

2026-01-25 03:34