Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals how controlled deformation of a key quantum model leads to the loss of topological order and a fundamental shift in its boundary conditions.

This paper investigates the impact of symmetry breaking on the toric code, demonstrating the collapse of higher-form symmetry and the emergence of string tension.

Topological order, a hallmark of exotic quantum phases, is often fragile in the face of perturbations that disrupt its underlying symmetries. This work, ‘Boundary and Symmetry Breaking in a Deformed Toric Code’, investigates how a controlled deformation of the toric code-a paradigmatic model of topological order-induces a phase transition accompanied by the spontaneous breaking of a higher-form symmetry. By examining the model on a cylindrical geometry and employing a holographic boundary Hamiltonian, we demonstrate that this transition is characterized by a reorganization of boundary conditions and a suppression of the effective central charge near the critical point. Does this symmetry breaking provide a general mechanism for understanding the instability of topological order in more complex quantum systems?

The Shifting Sands of Quantum Order

For over a century, scientists categorized phases of matter – solid, liquid, gas, and plasma – by how their symmetry is broken; a crystal, for instance, breaks the continuous translational symmetry of space. However, a revolutionary concept – topological order – proposes a fundamentally different way to classify matter. Unlike phases defined by symmetry breaking, topological phases are characterized not by what is broken, but by the global properties of the material and the unusual, emergent excitations within it. These excitations, known as anyons, behave unlike ordinary particles and are protected by the topology of the system, rendering the phase robust against local disturbances. This shift in perspective opens the door to a new understanding of quantum matter, where the overall ‘shape’ of the quantum state, rather than its local details, dictates its fundamental properties and potential for technological applications like robust quantum computing.

Unlike conventional phases of matter-such as solid, liquid, or gas-which are distinguished by the breaking of specific symmetries, topological order arises from the global properties of a system, rather than its local details. This means the overall arrangement and connectivity of the system dictate its behavior, even if local imperfections or distortions are present. Crucially, topological order manifests through the presence of emergent excitations – quasiparticles that aren’t fundamental constituents of the material but arise as collective behaviors. These excitations exhibit unusual statistical properties; exchanging two such particles can alter the system’s quantum state in ways impossible for conventional particles, leading to robustness against local perturbations and potentially enabling fault-tolerant quantum computation. This fundamentally different characterization of phases moves beyond simply identifying what symmetries are broken and instead focuses on the system’s inherent connectivity and the novel behaviors of its collective excitations.

The exploration of topological phases of matter necessitates a departure from the traditional toolkit of condensed matter physics, as these states are not adequately described by frameworks centered on local order parameters and symmetry breaking. Conventional methods, designed to identify phases through changes in material properties like magnetization or conductivity, fail to capture the subtle, global properties that define topological order. Instead, researchers are increasingly employing concepts from topology – a branch of mathematics concerned with properties preserved under continuous deformations – alongside tools from quantum information theory and many-body physics. This interdisciplinary approach is crucial for characterizing the exotic excitations, such as anyons with fractional statistics, that emerge in these systems and for distinguishing between different topological phases, which can exhibit the same local symmetries but drastically different global behaviors – a hallmark of their robustness and potential for fault-tolerant quantum computation.

The Toric Code: A Blueprint for Robustness

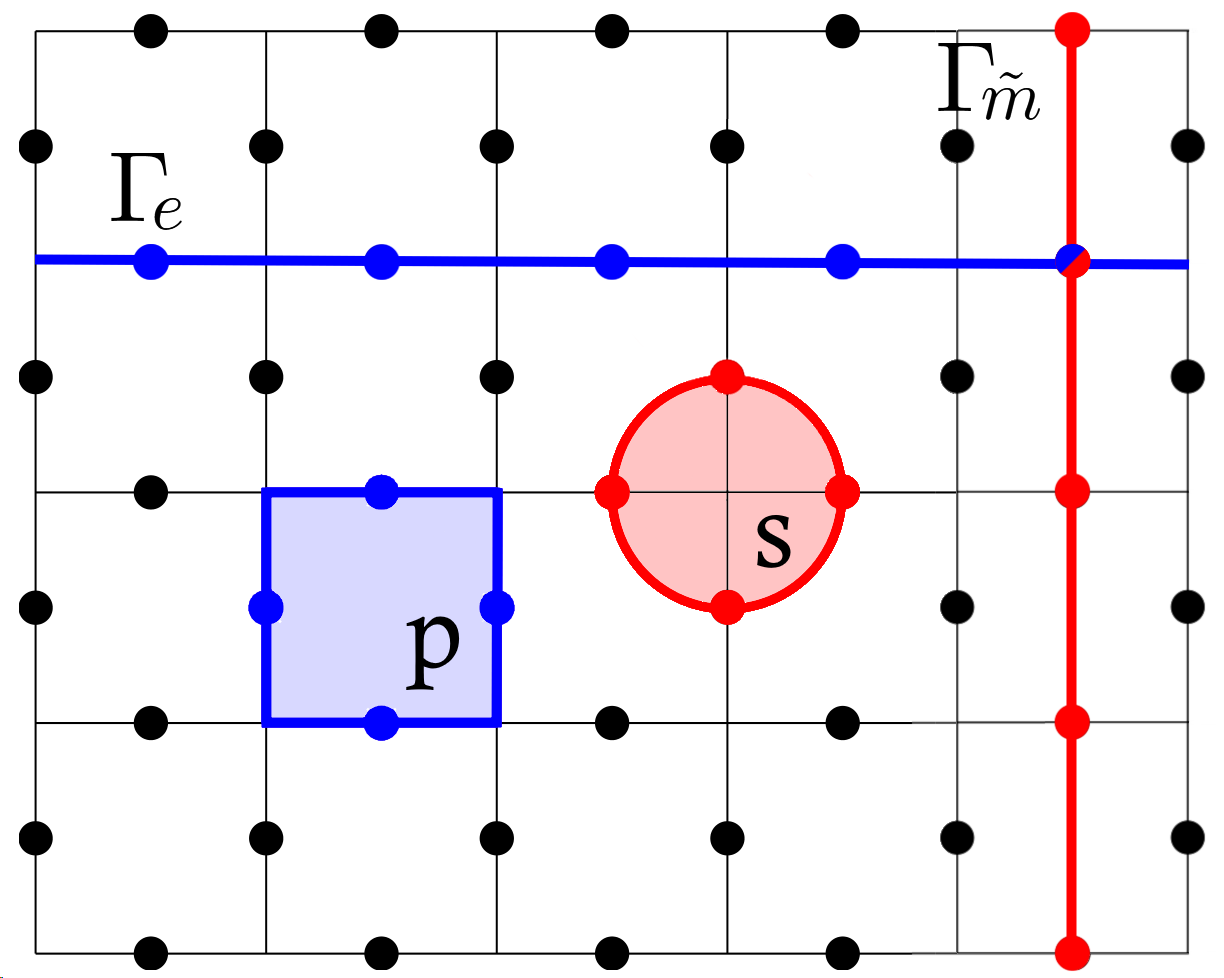

The toric code is defined by a Hamiltonian acting on a two-dimensional lattice with qubits located on edges. This Hamiltonian, consisting of terms representing star and plaquette operators \prod_{i \in \text{star}} \sigma^z_i and \prod_{i \in \text{plaquette}} \sigma^z_i respectively, allows for an exact solution due to its specific structure. This solvability reveals the presence of long-range entanglement, where qubits separated by large distances exhibit correlations beyond those explainable by local interactions. Furthermore, the model supports fractionalized excitations known as anyons – quasiparticles with exotic exchange statistics, specifically Majorana fermions, which are neither bosons nor fermions and arise as emergent properties of the entangled state. These anyons are not fundamental particles but collective excitations of the system, demonstrating a key characteristic of topological order.

The toric code’s robustness to local perturbations stems from its non-local degrees of freedom and the protection afforded by its topological properties. Local perturbations, such as those affecting individual qubits or bonds, cannot change the global topological state of the system because the relevant information is encoded in the collective properties of the entangled qubits. This means that small, localized errors do not lead to a corresponding change in the system’s ground state, preserving the long-range entanglement and preventing the system from becoming locally disordered. This resilience is a key characteristic distinguishing topologically ordered phases from conventional phases of matter, where local perturbations readily induce local changes in the system’s state.

Loop operators in the toric code, specifically Wilson and ’t Hooft loops, serve as diagnostic tools for identifying topological order by exhibiting non-local behavior. A Wilson loop, formed by tracing a contractible loop on the lattice, commutes with the Hamiltonian, indicating its insensitivity to local perturbations. Conversely, a ’t Hooft loop, tracing a loop that encloses a topological defect, does not commute with the Hamiltonian. The commutation relation – or lack thereof – between these loop operators and the Hamiltonian directly reveals the presence of topological order and characterizes the system’s long-range entanglement. Measuring the expectation value of these loops provides information about the system’s topological properties and the presence of anyonic excitations.

The Fragility of Order: Introducing Controlled Disorder

The Castelnovo-Chamon deformation of the toric code introduces localized interactions by adding terms to the Hamiltonian that act on small numbers of qubits. Specifically, this involves incorporating three-body interactions that favor certain spin configurations on the lattice. These terms are designed to break the global constraints that enforce topological order in the original toric code model. The strength of these added interactions is controllable, allowing for systematic investigation of the resulting phase transition. Unlike random perturbations, the Castelnovo-Chamon deformation maintains a specific, well-defined structure, enabling precise theoretical analysis and numerical simulations of the system’s behavior as the perturbation is increased.

The Castelnovo-Chamon deformation of the toric code is governed by a single parameter, β, which quantitatively defines the strength of the introduced local perturbations. A value of \beta = 0 corresponds to the original, unperturbed toric code, exhibiting topological order. Increasing β strengthens the local interactions, modifying the Hamiltonian and ultimately influencing the system’s quantum phase. The magnitude of β directly correlates with the degree to which the toric code’s properties are altered, and serves as the primary control knob for inducing a phase transition to a disordered state.

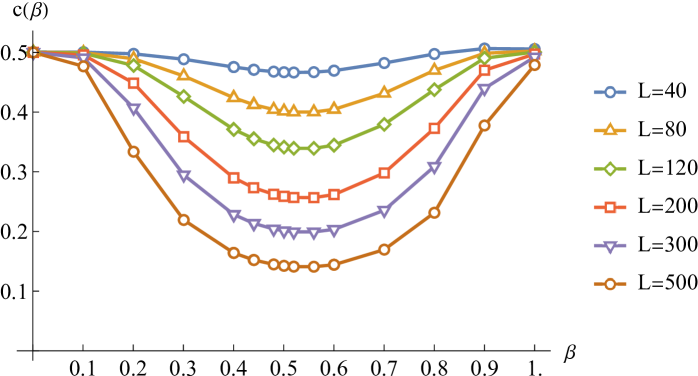

The toric code exhibits a phase transition from a topologically ordered state to a trivial, disordered state when subjected to the Castelnovo-Chamon deformation, controlled by the parameter β. Increasing β introduces local interactions that disrupt the long-range entanglement characteristic of the topologically ordered phase. This transition occurs at a critical coupling strength of approximately \beta_c \approx 0.44, beyond which the system no longer supports topologically protected excitations and behaves as a conventional, locally interacting system. Experimental and numerical investigations consistently identify this value as the demarcation between the ordered and disordered phases.

The Boundaries of Order: Probing Topology at the Edge

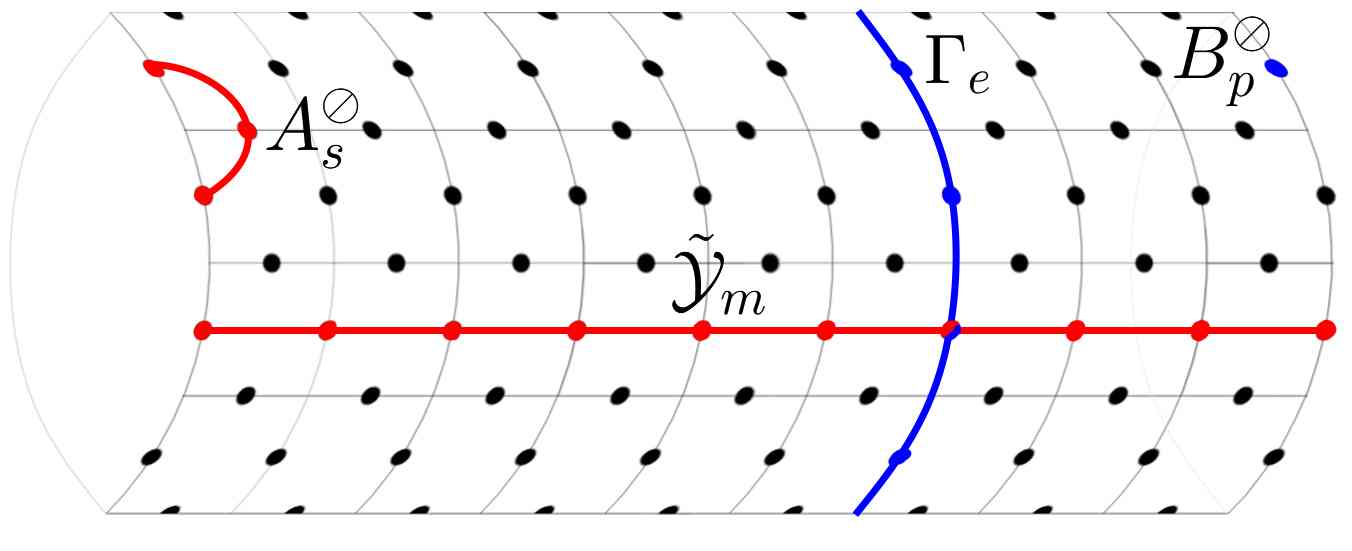

The imposition of open boundary conditions fundamentally alters the behavior of quantum systems by introducing spatial confinement. This confinement doesn’t simply truncate the system; it actively suppresses the propagation of loop operators – closed paths in the system – particularly in the vicinity of the boundary. These loop operators, crucial for characterizing topological order, effectively ‘short-circuit’ due to the limited space, reducing their contribution to the overall system properties. Consequently, the system exhibits modified entanglement characteristics and altered excitation spectra compared to its periodic boundary condition counterpart. This suppression isn’t a mere artifact of the boundary; it’s a key mechanism revealing the topological nature of the phase, as the boundary states are intrinsically linked to the non-trivial topology protected within the bulk of the material, and the reduced loop operator contributions are a signature of this connection.

The principle of bulk-boundary correspondence posits a profound relationship between the topological properties exhibited within a material’s interior – the ‘bulk’ – and the emergent behavior observed at its surfaces or edges – the ‘boundaries’. This isn’t merely a surface phenomenon; rather, the boundary states are fundamentally dictated by the topological invariants characterizing the bulk material. In essence, the boundaries act as ‘hinges’ revealing the hidden topological order residing within. Specifically, robust, protected states often appear at the boundary, even if the bulk material is insulating, and the number of these boundary states is directly linked to a topological invariant such as the Chern number or \mathbb{Z}_2 index calculated for the bulk. This correspondence offers a powerful framework for designing materials with tailored boundary properties and understanding phenomena like quantum Hall effects and topological insulators, where conducting surface states are guaranteed by the bulk’s topological order.

The bulk-boundary correspondence offers a remarkably potent method for dissecting and classifying topological phases of matter. This principle establishes a direct link between the system’s inherent properties within its interior – the ‘bulk’ – and the emergent behaviors observed at its edges or surfaces – the ‘boundary’. Instead of needing to analyze the complex, high-dimensional bulk directly, researchers can often characterize the entire topological phase simply by examining the protected edge states, which act as ‘footprints’ of the bulk topology. These boundary states are robust against local perturbations, ensuring the topological protection of the phase, and their properties – such as the number and nature of these states – provide definitive signatures for identifying different topological orders. Consequently, this correspondence not only simplifies the theoretical understanding of these exotic states of matter but also provides a practical pathway for their experimental detection and potential application in areas like robust quantum computation and novel electronic devices.

Toward a Deeper Understanding: Simulating the Quantum Landscape

Density Matrix Renormalization Group (DMRG) simulations offer a powerful computational approach to characterizing topological phases of matter, crucially through the precise calculation of the Central Charge. This value, denoted as c, serves as a fundamental descriptor within Conformal Field Theory (CFT), quantifying the number of effectively independent degrees of freedom at a critical point. A non-trivial c signals the presence of gapless excitations and long-range entanglement, hallmarks of exotic quantum phases beyond conventional descriptions. By accurately determining the Central Charge, DMRG not only validates the CFT description of the system but also provides a robust method for identifying and classifying different topological orders, even in the absence of a local order parameter. The ability to computationally access this key CFT parameter represents a significant advancement in understanding the emergent behavior of strongly correlated quantum systems.

The Transverse Field Ising Model, a cornerstone of condensed matter physics, reveals intriguing connections to the realm of Conformal Field Theory when examined through the lens of topological properties. This model, describing interacting spins subject to a magnetic field, isn’t merely a simplified representation of magnetism; its critical behavior allows for a mapping onto a Conformal Field Theory, a mathematical framework describing scale-invariant systems. This correspondence isn’t superficial-the model inherits characteristics like universal critical exponents and scaling laws from its CFT counterpart. Importantly, this mapping demonstrates that the fundamental topological features-those robust to local perturbations-are shared between seemingly disparate physical systems. Specifically, the model’s behavior near its quantum critical point mirrors the expected characteristics of a two-dimensional system governed by conformal symmetry, suggesting a deep underlying connection between magnetism and the broader principles of quantum field theory. This equivalence provides a powerful tool for understanding and characterizing topological phases of matter, enabling researchers to leverage the well-developed machinery of CFT to analyze complex magnetic systems.

Investigations into the Transverse Field Ising Model reveal a fascinating shift in its behavior as the system nears a critical coupling strength of approximately 0.44. At this point, calculations demonstrate a suppression of the central charge – a value intrinsically linked to the number of independent degrees of freedom and the scaling of entanglement. This suppression doesn’t signify a simple transition to a different phase, but rather indicates a breakdown in the expected conformal entanglement scaling, hinting at the emergence of a unique, gapless intermediate regime. This regime is characterized by excitations with arbitrarily small energy, deviating from the typical behavior of either gapped or fully gapless conformal field theories and offering a glimpse into more complex quantum phases of matter. The observation suggests the model’s entanglement structure is fundamentally reorganizing, moving beyond standard conformal descriptions as β approaches \beta_c.

The pursuit of order, even in seemingly stable systems, reveals a fragility inherent in all constructed things. This work, detailing the collapse of topological order within a deformed toric code, echoes a timeless truth: boundaries shift, symmetries break, and what appears solid yields to inevitable change. As Albert Camus observed, “The only way to deal with an unfree world is to become so absolutely free that your very existence is an act of rebellion.” The researchers demonstrate how introducing string tension-a controlled deformation-destroys the higher-form symmetry, reorganizing the holographic boundary. It’s a reminder that every attempt to define a system, to impose order, is also a prophecy of its eventual unraveling, a growth process not unlike watching clouds fall and monoliths rise again.

What Lies Beyond?

The deliberate fracturing of topological order, as demonstrated by this work on the deformed toric code, is not a failure of construction, but a glimpse into the inevitable. Long stability is the sign of a hidden disaster; the toric code, seemingly robust, reveals its susceptibility to even gentle prodding. The collapse of 1-form symmetry isn’t an anomaly to be corrected, but a fundamental phase transition-a reorganization of the landscape. The careful tuning of string tension offers not control, but a means to observe the system selecting its own, less-ordered ground state.

The reorganization of boundary conditions deserves particular attention. The holographic boundary, a construct born of theoretical convenience, has proven remarkably sensitive to these deformations. This suggests that much of what is considered ‘order’ in these systems is merely a specific way of looking at the edge-a convenient fiction. Future work will inevitably grapple with the question of whether this boundary is truly fundamental, or an emergent property of the internal entanglement.

The true challenge lies not in building more resilient codes, but in understanding the principles that govern their decay. Systems don’t fail – they evolve into unexpected shapes. The careful measurement of critical exponents and the detailed mapping of the phase diagram are merely the first steps in charting the topography of this inevitable descent. The next generation of research will not seek to preserve order, but to understand the beautiful, complex patterns that emerge from its ruins.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.04002.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- How to Unlock the Mines in Cookie Run: Kingdom

- Solo Leveling: Ranking the 6 Most Powerful Characters in the Jeju Island Arc

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Bitcoin’s Big Oopsie: Is It Time to Panic Sell? 🚨💸

- Bitcoin Frenzy: The Presales That Will Make You Richer Than Your Ex’s New Partner! 💸

- Gears of War: E-Day Returning Weapon Wish List

- The Saddest Deaths In Demon Slayer

- How to Find & Evolve Cleffa in Pokemon Legends Z-A

- Most Underrated Loot Spots On Dam Battlegrounds In ARC Raiders

- Rocket League: Best Controller Bindings

2026-02-06 01:36