Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new analysis provides a standardized framework for comparing the speed of ten finalist algorithms in the NIST Lightweight Cryptography competition.

This paper presents a unified time-complexity characterization of NIST Lightweight Cryptography finalists for resource-constrained environments.

Despite the increasing demand for cryptographic solutions in resource-constrained environments, a unified theoretical understanding of performance scaling among lightweight cryptographic primitives has remained elusive. This paper, ‘Time-Complexity Characterization of NIST Lightweight Cryptography Finalists’, addresses this gap by introducing a symbolic model for formally deriving the time complexity of each of the ten finalist algorithms from the NIST Lightweight Cryptography competition. The resulting analysis clarifies how design parameters influence computational scaling and provides a comparative foundation for selecting efficient primitives in mobile and embedded systems. Will this framework enable the development of more robust and performant security systems tailored to the unique challenges of constrained devices?

The Evolving Landscape of Resource-Constrained Cryptography

Conventional cryptographic algorithms, while robust, frequently require significant processing power, memory, and energy-resources that are often limited or unavailable in the rapidly expanding world of Internet of Things (IoT) and embedded systems. Algorithms like RSA and AES, designed for servers and desktops, present a considerable challenge for low-power devices such as sensors, wearables, and microcontrollers. The computational burden can lead to slower operation, reduced battery life, and even render certain security measures impractical for these resource-constrained platforms. This disparity between the demands of traditional cryptography and the capabilities of modern connected devices has created a critical need for alternative approaches that prioritize efficiency without compromising security, driving innovation in the field of lightweight cryptography.

The exponential growth of interconnected devices, ranging from smart home appliances to industrial sensors, presents a unique challenge to conventional cryptography. Traditional encryption methods, while robust, often require considerable processing power, memory, and energy – resources severely limited in many Internet of Things (IoT) and embedded systems. This constraint has driven a necessary evolution towards ‘Lightweight Cryptography,’ a specialized field focused on designing algorithms specifically optimized for minimal resource usage. These algorithms prioritize efficiency without compromising essential security properties, enabling secure communication and data protection on devices where computational limitations previously precluded effective cryptographic implementation. The development of lightweight cryptography is therefore not merely an academic pursuit, but a crucial enabler for the continued expansion and secure operation of the increasingly connected world.

Driven by the expanding universe of interconnected devices, cryptographic research is undergoing a notable evolution, prioritizing designs that skillfully balance robust security with minimized resource consumption. This isn’t simply about shrinking existing algorithms; it necessitates entirely new approaches to encryption and authentication. Researchers are actively exploring techniques like Boolean functions with fewer gates, utilizing smaller key sizes without compromising confidentiality, and developing algorithms specifically tailored for constrained hardware architectures. These innovations extend beyond computational efficiency to encompass reduced memory footprint and lower energy demands – crucial factors for battery-powered devices and large-scale deployments. The pursuit of these ‘lightweight’ cryptographic solutions represents a fundamental shift, aiming to democratize security by making it accessible to the increasingly pervasive world of the Internet of Things.

Recognizing the growing need for cryptographic solutions suited to resource-constrained devices, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) initiated a standardization process to identify and validate lightweight cryptographic algorithms. This rigorous evaluation aims to ensure broad interoperability and confidence in the security of these designs as they are integrated into the expanding landscape of Internet of Things and embedded systems. Complementing this effort, a recent publication details a unified framework for analyzing the time complexity of these algorithms, providing a standardized methodology to compare their efficiency and performance characteristics. This framework moves beyond simple benchmark comparisons, offering a more nuanced understanding of how these algorithms scale with varying resource limitations, ultimately guiding the selection and implementation of secure, lightweight cryptography for widespread adoption.

The Fundamental Building Blocks: Primitives and Constructions

Stream ciphers achieve rapid encryption by generating a keystream which is combined with the plaintext. Lightweight algorithms often utilize stream cipher principles due to their low computational complexity and minimal memory footprint. However, the security of these algorithms is heavily dependent on the key scheduling algorithm used to expand the initial key into a pseudorandom keystream. Poorly designed key scheduling algorithms can introduce vulnerabilities, such as statistical biases or predictable keystream generation, potentially allowing an attacker to recover the plaintext. Therefore, careful consideration must be given to the design and analysis of the key scheduling algorithm, including its resistance to known attacks and its ability to produce a sufficiently random and unpredictable keystream over extended periods of operation.

Block cipher designs, characterized by their strong cryptographic properties, often require significant computational resources for both encryption and decryption. Implementation in resource-constrained environments – such as embedded systems, IoT devices, or mobile platforms – therefore necessitates optimization techniques. These include reducing the cipher’s block size, minimizing the number of rounds, employing techniques like diffusion layer simplification, and leveraging hardware acceleration where available. Furthermore, careful attention to memory footprint is crucial, demanding efficient key scheduling algorithms and compact storage of intermediate values. The trade-off between security level and resource usage is a primary consideration when adapting block ciphers for these applications.

Sponge constructions represent a class of cryptographic primitives gaining prominence in modern designs due to their adaptability and performance characteristics. These constructions operate by absorbing input data through a permutation function applied iteratively to an internal state, followed by a squeezing phase to extract the output. The core strength lies in the ability to adjust the rate (input/output block size) and capacity (size of the internal state) to trade off performance against security levels. This flexibility allows a single underlying permutation function to be used in various modes, including hashing, stream ciphers, and authenticated encryption. The simplicity of the core permutation, often based on ARX operations, facilitates efficient hardware and software implementations, making sponge constructions well-suited for resource-constrained environments.

ARX operations – Addition, Rotation, and XOR – are widely implemented in cryptographic designs due to their suitability for efficient hardware realization. Addition and XOR are single-cycle operations on most processor architectures, and rotation can be implemented with minimal gate count. This characteristic minimizes latency and power consumption, particularly crucial in resource-constrained environments like embedded systems or IoT devices. The simplicity of these operations also facilitates formal verification and side-channel analysis resistance, increasing confidence in the security of the resulting cryptographic implementation. Consequently, cryptographic primitives built upon ARX operations often exhibit a favorable performance-to-cost ratio when deployed in hardware.

Diverse Lightweight Designs in Practice

Ascon and PHOTON-Beetle are representative examples of cryptographic algorithms built upon the Sponge Construction principle, which relies on a permutation-based design. The Sponge Construction utilizes a fixed-length permutation function applied iteratively to a state, absorbing input data and then squeezing out the resulting output. Both algorithms employ a permutation – a non-invertible transformation – as their core component, repeatedly applying it to modify the state during both the absorbing and squeezing phases. This approach provides a high degree of diffusion and confusion, contributing to the algorithms’ security, and allows for flexible parameterization to accommodate varying security levels and performance requirements. The permutation within these algorithms operates on a fixed-size state, processing data in blocks to efficiently transform the internal state with each iteration.

Grain-128AEAD is a stream cipher designed for high-speed operation and minimal latency in authenticated encryption scenarios. Its time complexity is linearly proportional to the combined size of the message (|M|) and associated data (|AD|), denoted as O(|M|+|AD|). This linear scaling means that processing time increases directly with data volumes, making it particularly efficient for applications requiring rapid encryption or decryption of varying-length inputs. The cipher achieves this performance through a streamlined design focusing on bit-oriented operations and avoiding complex table lookups or large data dependencies.

GIFT-COFB is a block cipher implementation distinguished by its use of COFB (Counter with Cipher Block Chaining Feedback) mode. This design choice results in a linear time complexity of O(\ell_A + \ell_M), where \ell_A represents the length of the associated data and \ell_M represents the length of the message. This simplicity stems from COFB’s predictable data dependency, allowing for efficient parallelization and reduced computational overhead compared to more complex cipher modes. The cipher’s performance is directly proportional to the input data size, making it suitable for resource-constrained environments where predictable execution time is critical.

TinyJAMBU achieves lightweight cryptographic operation through the utilization of a 128-bit Non-linear Feedback Shift Register (NFSR) incorporating dual permutation layers. This design employs 32-bit data blocks, enabling a more granular assessment of time complexity compared to algorithms operating on larger block sizes. The use of dual permutations within the NFSR contributes to increased diffusion and confusion, enhancing security without significantly increasing computational overhead. This block size allows for optimized implementation on resource-constrained devices, and facilitates precise calculation of operational costs based on the number of 32-bit operations performed.

Performance and Optimization: A Quantitative Perspective

Time complexity analysis serves as a foundational element in evaluating cryptographic algorithms, particularly when deployed in environments with limited processing power, memory, or energy – such as embedded systems, IoT devices, or mobile platforms. This assessment doesn’t measure absolute execution time, but rather how the computational cost of an algorithm scales with increasing input size; algorithms exhibiting lower time complexity – denoted using Big O notation like O(n) or O(n^2) – will generally perform more efficiently as data volumes grow. For instance, an algorithm with O(n) complexity will double its processing time when the input size doubles, while one with O(n^2) complexity will quadruple its processing time. Consequently, a rigorous understanding of time complexity is critical for selecting and optimizing algorithms to ensure practical performance and feasibility in resource-constrained scenarios, directly impacting the security and usability of cryptographic implementations.

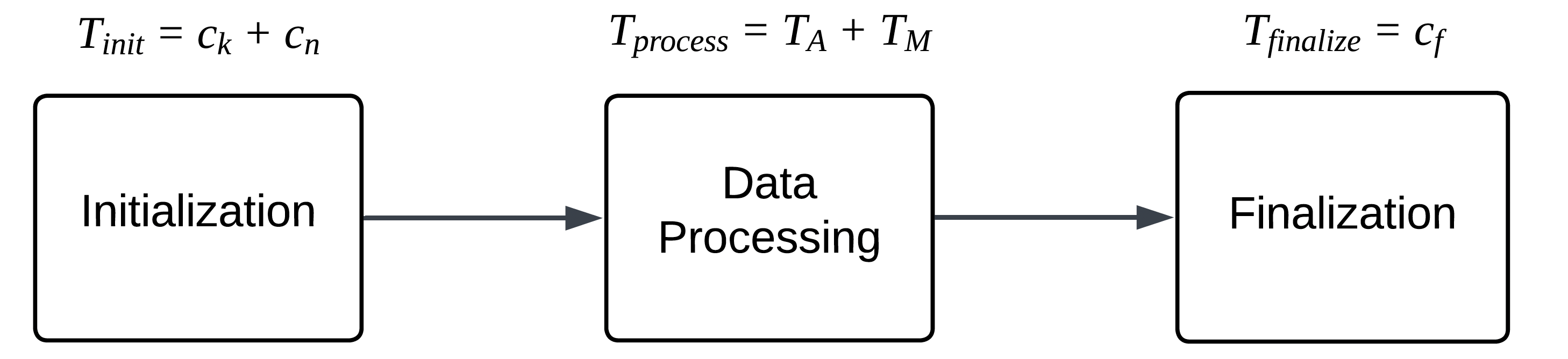

A detailed understanding of algorithmic efficiency benefits from dissecting overall performance into distinct phases. The Three-Phase Complexity Model achieves this by separating computation into initialization, data processing, and finalization stages; this granular approach moves beyond simple operation counts to reveal where an algorithm spends the most resources. Initialization encompasses setup tasks performed once before processing any data, while the data processing phase represents the core computational loop, scaled by the input data size. Finally, the finalization phase accounts for any concluding steps needed after processing all data. By analyzing each phase independently, researchers gain a more nuanced understanding of an algorithm’s strengths and weaknesses, facilitating targeted optimizations and informed comparisons between different approaches – crucial for resource-constrained environments or high-throughput applications.

Modern cryptographic designs, exemplified by algorithms like Elephant and Romulus, are increasingly focused on minimizing computational overhead through innovative approaches to masking and tweakable block ciphers. These algorithms employ techniques such as wide-branch diffusion and the use of dedicated hardware instructions to accelerate operations, particularly relevant in constrained environments like embedded systems and IoT devices. Masking, a security measure against side-channel attacks, is integrated in a way that reduces performance penalties, while tweakable block ciphers allow for efficient key and nonce management without requiring separate encryption rounds. This emphasis on efficiency isn’t merely about speed; it directly impacts energy consumption, making these designs suitable for applications where battery life or processing power is limited, and ensuring robust security doesn’t come at an unacceptable cost.

A recent comparative study rigorously quantified the time complexity of several candidate algorithms in a competitive evaluation, revealing significant performance differences. Notably, ASCON and PHOTON-Beetle exhibited among the most efficient scaling profiles; ASCON’s complexity is expressed as O(lA⋅b+lP⋅b), while PHOTON-Beetle’s is defined as O(\lceil|A|/r\rceil⋅b+\lceil|M|/r\rceil⋅b). In contrast, SPARKLE demonstrated a comparatively higher complexity, quantified as O(2⋅|A|/r⋅b+3⋅|M|/r⋅b+d/r⋅b+2b). These findings, derived from detailed algorithmic analysis, highlight the importance of complexity as a critical metric in assessing the suitability of cryptographic primitives for resource-constrained environments and applications demanding high throughput.

The pursuit of efficient cryptography, as demonstrated by this time-complexity analysis, often necessitates difficult trade-offs. One must carefully consider which operations to prioritize and which to streamline, acknowledging that a truly elegant solution isn’t about minimizing all costs, but rather, intelligently distributing them. As Marvin Minsky observed, “The more of its internal workings you lay bare, the more fragile it seems.” This fragility extends to cryptographic designs; optimizing for speed alone can introduce vulnerabilities if the underlying structure lacks robustness. The paper’s unified framework, by explicitly characterizing these complexities, provides a necessary lens for evaluating the inherent trade-offs within each NIST finalist, recognizing that architecture-the deliberate choice of what to sacrifice-dictates performance in resource-constrained environments.

What’s Next?

The presented framework, while offering a comparative lens for these lightweight cryptographic algorithms, ultimately highlights the inherent trade-offs in pursuing optimization at this level of abstraction. The analysis reveals not a search for the ‘fastest’ cipher, but rather an exercise in understanding where complexity concentrates – and therefore, where future gains will diminish. One suspects that diminishing returns will be the defining characteristic of this field; the pursuit of marginal speed improvements will invariably introduce hidden costs in implementation, power consumption, or, crucially, security.

The current work focuses on time complexity, but a holistic assessment demands a concurrent analysis of other resource constraints-memory footprint, energy expenditure, and resistance to side-channel attacks. These are not independent variables. Optimizing for one often exacerbates vulnerabilities in another. A truly scalable solution will not be found through clever algorithmic tweaks, but through a re-evaluation of the fundamental architectural choices-a shift towards simplicity, even if it means accepting a degree of theoretical sub-optimality.

The architecture of security systems is often invisible until it fails. Future research should prioritize formal verification and robust, standardized benchmarking-not merely in idealized computational models, but on the diverse range of resource-constrained devices that represent the true deployment landscape. Dependencies are the true cost of freedom; a proliferation of complex cryptographic primitives will only increase the attack surface and the burden of maintaining secure systems.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.05641.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- How to Unlock the Mines in Cookie Run: Kingdom

- Solo Leveling: Ranking the 6 Most Powerful Characters in the Jeju Island Arc

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Bitcoin Frenzy: The Presales That Will Make You Richer Than Your Ex’s New Partner! 💸

- Bitcoin’s Big Oopsie: Is It Time to Panic Sell? 🚨💸

- Gears of War: E-Day Returning Weapon Wish List

- Most Underrated Loot Spots On Dam Battlegrounds In ARC Raiders

- The Saddest Deaths In Demon Slayer

- How to Find & Evolve Cleffa in Pokemon Legends Z-A

- Rocket League: Best Controller Bindings

2026-02-06 15:26