Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new analysis demonstrates how strategic geometric arrangements of optical lattice clocks can enhance the sensitivity of networks designed to detect the subtle ripples of the gravitational wave background.

Researchers derive geometric transformations for optical lattice clock networks that preserve cross-correlation, enabling optimized detector configurations for improved stochastic gravitational wave background detection.

Detecting the stochastic gravitational wave background remains a significant challenge in modern astrophysics, requiring increasingly sensitive detector networks. This is addressed in ‘Detecting gravitational wave background with equivalent configurations in the network of space based optical lattice clocks’, which investigates geometric transformations for networks of space-based optical lattice clocks (OLCs) that preserve cross-correlation responses. The authors analytically demonstrate a configuration transformation applicable to two-detector OLC networks, mapping suboptimal layouts to those with enhanced sensitivity-comparable to space-based laser interferometers. Could this approach unlock a novel pathway towards optimizing gravitational wave detection beyond current technologies and network designs?

The Expanding Echoes of Spacetime

The advent of ground-based gravitational wave detectors, most notably the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) and Virgo, fundamentally altered the landscape of astronomy. Prior to these instruments, observations of the universe were almost exclusively limited to electromagnetic radiation – light, radio waves, X-rays, and so on. LIGO and Virgo, however, directly detect ripples in spacetime itself – gravitational waves – generated by the violent mergers of compact binary systems, such as black holes and neutron stars. These detections, beginning in 2015, not only confirmed a key prediction of Einstein’s theory of general relativity, but also opened a new window onto the cosmos, allowing scientists to observe events previously hidden from view. By pinpointing the sources of these waves, astronomers are now able to study the properties of black holes and neutron stars, test the limits of gravity, and gain insights into the formation and evolution of these exotic objects, effectively ushering in the era of multi-messenger astronomy where gravitational waves complement traditional electromagnetic observations.

Current gravitational wave detectors, like LIGO and Virgo, excel at capturing the ripples created by the collision of stellar-mass black holes and neutron stars, but their sensitivity plateaus at lower frequencies. This limitation obscures a significant portion of the gravitational wave spectrum, preventing a complete understanding of events involving supermassive black hole mergers at galactic centers, or the dynamics of active galactic nuclei. These phenomena produce gravitational waves with periods of months to years, far below the detectable range of ground-based interferometers. Consequently, researchers are actively pursuing complementary detection methods – such as Pulsar Timing Arrays – to fill this critical gap and unveil the hidden universe of low-frequency gravitational radiation, promising insights into the co-evolution of galaxies and their central black holes.

Pulsar Timing Arrays represent a distinct method for detecting gravitational waves, differing significantly from ground-based interferometers by observing subtle shifts in the arrival times of radio pulses from millisecond pulsars. This technique necessitates years of meticulous data collection from numerous pulsars across the sky, demanding extensive computational resources for analysis and signal processing. A key challenge lies in disentangling the faint gravitational wave signal from a variety of confounding ‘astrophysical foregrounds’ – noise generated by unresolved sources and interstellar medium fluctuations – which can obscure or mimic the sought-after waveform. Despite these complexities, PTAs hold immense promise for revealing the existence of supermassive black hole binaries and potentially unlocking insights into the very early universe, complementing the findings from traditional gravitational wave detectors and opening a new window onto the cosmos.

Atomic Clocks: A New Architecture for Gravitational Sensing

Optical lattice clocks (OLCs) offer a novel approach to gravitational wave detection by utilizing the high stability of atomic clocks to measure minute variations in spacetime. These clocks trap neutral atoms at discrete lattice sites created by interfering laser beams, enabling exceptionally precise frequency measurements – currently achieving fractional frequency uncertainties below 10^{-{18}}. Gravitational waves induce distortions in spacetime, causing measurable shifts in the atomic transition frequencies observed by the OLCs. By comparing the timing signals from multiple, spatially separated OLCs, changes indicative of a passing gravitational wave can be detected. This technique circumvents the need for kilometer-scale interferometers, offering a potentially more compact and cost-effective means of observing these phenomena, particularly in the low-frequency range where traditional detectors are less sensitive.

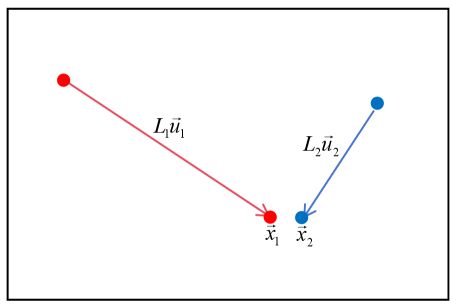

Correlating the timing signals from multiple optical lattice clocks (OLCs) functions as a distributed interferometer for gravitational wave detection. Traditional interferometers, such as LIGO and Virgo, rely on measuring changes in the length of physical arms to detect spacetime distortions. In contrast, an OLC network establishes a baseline using the separation between clocks, with timing differences representing phase shifts induced by a gravitational wave. This approach circumvents the need for kilometer-scale physical arms, significantly reducing infrastructure costs and susceptibility to environmental noise. The sensitivity scales with the number of clocks and their separation, allowing for the construction of a large-scale detector without the engineering challenges associated with massive, monolithic structures.

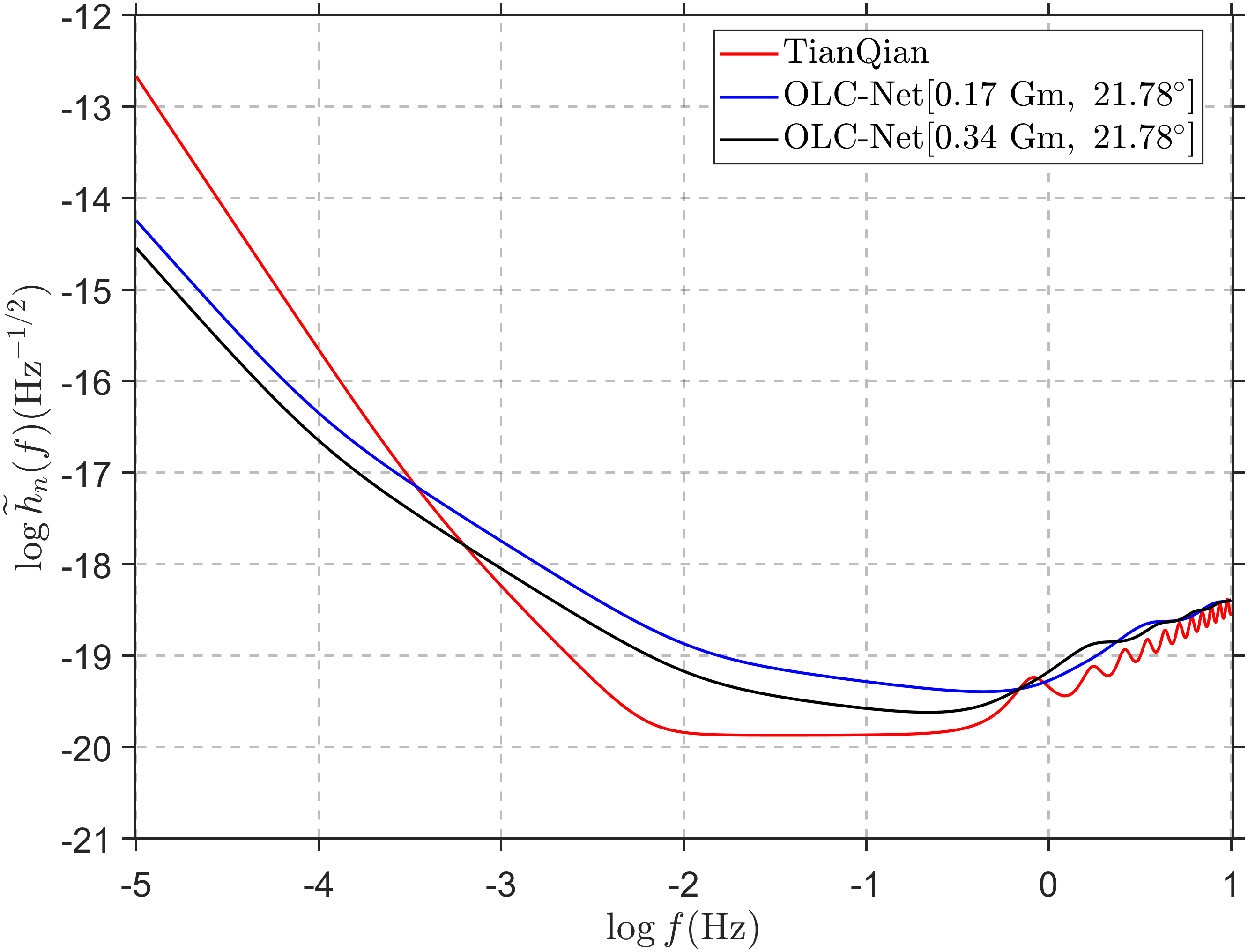

Traditional gravitational wave detectors, such as laser interferometers like LIGO and Virgo, exhibit decreasing sensitivity at low frequencies – below approximately 10 Hz – due to limitations imposed by seismic noise and the length of their physical arms. Optical Lattice Clocks (OLCs), however, circumvent these limitations by functioning as array-based detectors where timing correlations, rather than physical displacement measurements, are the primary observation method. This allows OLCs to achieve substantially improved sensitivity in the low-frequency range – from 10-3 Hz to 1 Hz and below – potentially revealing gravitational wave signals from supermassive black hole binaries, extreme mass ratio inspirals, and other astrophysical phenomena currently inaccessible to conventional detectors, effectively opening a new and complementary window for gravitational wave astronomy.

Network Geometry and the Pursuit of Correlation

Cross-correlation analysis is a fundamental technique employed in the operation of Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) networks to isolate gravitational wave signals from inherent noise. This process involves comparing signals received from multiple detectors to identify correlated events exceeding the noise floor. A key characteristic of optimally configured networks is the equality of cross-correlation responses between detector pairs; specifically, the magnitudes of the cross-correlation functions |ℛ<sub>12</sub>(f)| and |ℛ<sub>34</sub>(f)| must be equal across all frequencies, f. This equality ensures that signals are not preferentially attenuated or amplified due to network geometry, maximizing the signal-to-noise ratio and allowing for the detection of weaker gravitational wave events.

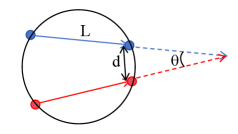

Geometric Configuration Transformation within an Optical Lever Configuration (OLC) network enables detector arrangements beyond traditional linear layouts while maintaining cross-correlation signal strength. This is achieved by mathematically relating the positions and orientations of individual OLCs to preserve the |ℛ12(f)| = |ℛ34(f)| relationship, which defines equal cross-correlation responses. The transformation allows for non-trivial configurations – including triangular or irregular placements – without compromising the network’s ability to extract gravitational wave signals from noise; this flexibility is beneficial when site constraints limit detector placement options or when optimizing for specific signal characteristics.

Minimizing effective strain noise in an optical lever chain (OLC) network requires a correlated understanding of noise characteristics and the physical arm length L. Noise correlation, specifically the degree to which noise is shared between detectors, directly impacts the signal-to-noise ratio; reducing correlated noise enhances detection capabilities. The arm length L scales the effect of strain on the measured signal; therefore, optimizing L in conjunction with noise correlation allows for maximizing sensitivity to gravitational wave signals. Careful consideration of these two parameters during network configuration is essential for achieving optimal performance and detecting weak signals otherwise obscured by noise.

Optimized network configurations, achieved through considerations of noise correlation and arm length, substantially improve the signal-to-noise ratio for gravitational wave detection. This enhancement allows the observation of weak signals that would otherwise be obscured by the inherent noise floor of the detector network. By minimizing effective strain noise, the optimized arrangement effectively lowers the detection threshold, enabling the identification of events with lower amplitudes and increasing the probability of detecting previously undetectable gravitational wave sources. The improved sensitivity is not simply a matter of signal amplification, but rather a reduction in the noise that masks the signal, thus providing a crucial pathway for expanding the range and capabilities of the detector network.

Mapping the Universe Through Gravitational Harmonies

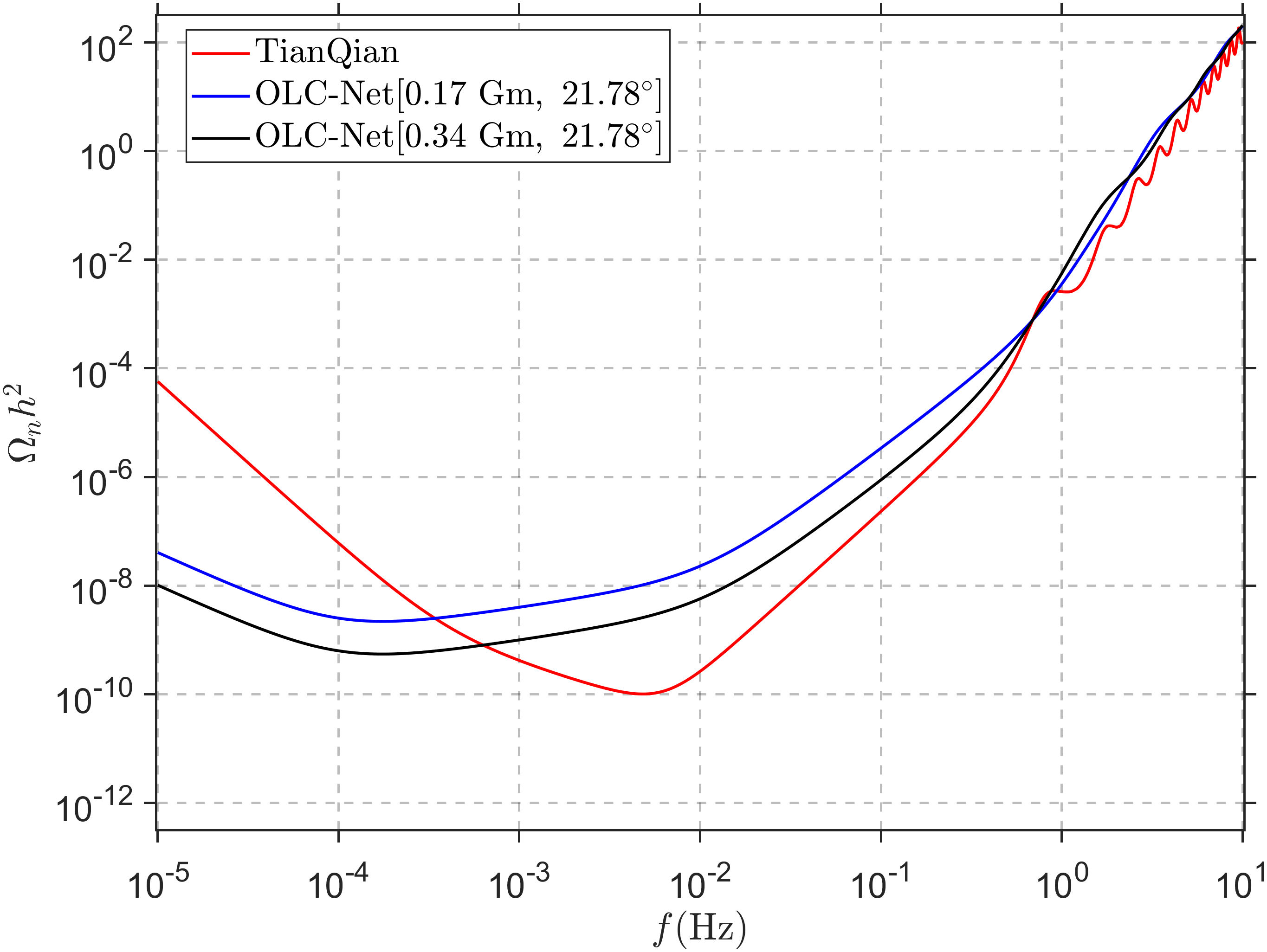

The universe hums with gravitational waves, and characterizing their collective energy – through the dimensionless Gravitational-Wave Energy Density Spectrum – offers a powerful new window into the cosmos. This spectrum isn’t simply a measure of total energy, but a detailed fingerprint revealing the sources contributing to the background signal. Specifically, researchers aim to discern the prevalence and characteristics of supermassive black hole binaries – colossal pairs of black holes orbiting each other – which are predicted to be significant low-frequency wave emitters. By precisely mapping the spectrum, scientists can estimate the number of these binaries, their masses, and orbital properties, effectively constructing a census of these hidden galactic engines. Beyond black hole binaries, the spectrum’s nuances can also unveil the contributions from other exotic sources, like early universe processes or populations of smaller, merging black holes, thereby painting a comprehensive picture of the gravitational wave universe and its evolution.

A truly comprehensive view of the gravitational wave universe demands a multi-faceted approach, and advancements in measuring the dimensionless gravitational-wave energy density spectrum are poised to significantly enhance the capabilities of upcoming space-based observatories. Missions like LISA, Taiji, and TianQin are specifically designed to detect low-frequency gravitational waves – signals often missed by ground-based detectors – but their full potential is unlocked when combined with precise spectral characterization. This improved understanding acts as a crucial calibration tool, allowing scientists to more accurately interpret the data received from these complex instruments and disentangle the overlapping signals from numerous sources. Ultimately, this synergy will not only refine the identification of supermassive black hole binaries and other exotic phenomena, but also establish a robust foundation for future gravitational wave astronomy, revealing a previously inaccessible realm of cosmic events.

The convergence of gravitational wave observatories – including space-based missions like LISA, Taiji, and TianQin alongside ground-based detectors – heralds a transformative era for astrophysics and cosmology. These technologies, designed to detect ripples in spacetime across a broader frequency range than ever before, promise to unveil a hidden universe previously inaccessible to traditional electromagnetic observation. By probing the dynamics of supermassive black hole mergers, the evolution of galactic nuclei, and potentially even the very early universe, this multi-messenger approach offers a novel window into extreme gravitational environments. The sheer volume of data anticipated from this combined effort will necessitate innovative data analysis techniques and theoretical modeling, but the potential rewards – a deeper understanding of gravity, black holes, and the cosmos’s fundamental building blocks – are immense, promising to reshape current cosmological models and reveal previously unknown phenomena.

The pursuit of optimal detector network layouts, as explored in this study, echoes a principle found not in engineering, but in gardening. One arranges the components not for static perfection, but for a forgiving interconnectedness. As Epicurus observed, “It is not the possession of the largest garden that provides the most pleasure, but the enjoyment of it.” Similarly, this work demonstrates that maintaining equal cross-correlation responses through geometric transformations-effectively tending to the ‘garden’ of detector configurations-is paramount. The study’s analytical derivations offer a means to cultivate sensitivity, recognizing that resilience lies not in isolating detectors, but in fostering a harmonious interplay between them, even amidst the stochastic noise of the gravitational wave background.

The Horizon Recedes

The pursuit of gravitational wave backgrounds, even with exquisitely precise instruments like optical lattice clocks, reveals less about conquering noise and more about cultivating its complexity. This work, in seeking ‘equivalent configurations’, does not truly solve the problem of detector layout. It merely pushes the inevitability of diminishing returns further down the path. Each transformation, each optimized network, is a temporary reprieve, a localized victory against the entropic tide. The universe does not offer perfect symmetries; it offers only imperfect reflections, and any attempt to impose ideal geometries will ultimately be frustrated by the real, messy distribution of spacetime itself.

The analytic tools presented here are less a blueprint for construction than a method for charting the landscape of failure. Understanding how a network degrades under perturbation, rather than striving for an unattainable stability, is the more honest endeavor. Future work will inevitably grapple with the limitations of these geometric idealizations, the subtle distortions introduced by manufacturing imperfections, and the ever-present challenge of isolating a stochastic signal from a sea of correlated, yet unpredictable, local disturbances.

It is a curious paradox: the more precisely one measures, the more acutely one feels the imprecision of the universe. The study of gravitational waves, particularly the background, is not a quest for signal, but a cartography of ignorance. Each detection is not an arrival, but a revelation of how much remains unseen, and how little control one truly possesses over the instruments used to observe it.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.05714.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- How to Unlock the Mines in Cookie Run: Kingdom

- Solo Leveling: Ranking the 6 Most Powerful Characters in the Jeju Island Arc

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Bitcoin Frenzy: The Presales That Will Make You Richer Than Your Ex’s New Partner! 💸

- YAPYAP Spell List

- Gears of War: E-Day Returning Weapon Wish List

- Bitcoin’s Big Oopsie: Is It Time to Panic Sell? 🚨💸

- How to Find & Evolve Cleffa in Pokemon Legends Z-A

- Most Underrated Loot Spots On Dam Battlegrounds In ARC Raiders

- Top 8 UFC 5 Perks Every Fighter Should Use

2026-02-08 21:01