Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new study uses correlation diagrams to explore how the vibrational spectrum of the KCN molecule transitions from order to chaos as energy increases.

Analysis of correlation diagrams reveals scarring linked to 1:2 quantum resonances in the vibrational dynamics of highly nonlinear floppy molecules like KCN.

Understanding the vibrational spectra of highly nonlinear molecules remains challenging due to the complex interplay between order and chaos in their dynamics. This is addressed in ‘Using correlation diagrams to study the vibrational spectrum of highly nonlinear floppy molecules: The K-CN case’, which explores the quantum dynamics of the K-CN molecule by employing correlation diagrams with a variable Planck constant. The analysis reveals a quantum transition from order to chaos, manifested as a frontier of scarred functions and the emergence of diabatic states corresponding to classical Kolmogorov-Arnold-Moser tori. Could this approach provide a more intuitive pathway to interpreting the vibrational spectra of other complex, floppy molecules and ultimately predict their chemical behavior?

The Fragile Order of Potassium Cyanide

The seemingly simple potassium cyanide (KCN) molecule presents a fascinating challenge to conventional chemical analysis due to its unexpectedly complex, chaotic behavior. While possessing only three atoms, KCN’s vibrational dynamics deviate significantly from the predictable patterns observed in most diatomic or triatomic systems. Traditional methods, reliant on harmonic approximations and perturbative calculations, struggle to accurately model its energy flow and spectral features. This nonlinearity arises from the molecule’s unique combination of a light atom (carbon) bonded to both a heavy atom (potassium) and a relatively electronegative nitrogen. The resulting interplay of stretching and bending motions leads to a highly sensitive potential energy surface, promoting the emergence of chaotic trajectories even at low energies – a phenomenon that demands sophisticated analytical techniques and a reevaluation of established molecular modeling paradigms.

The seemingly simple KCN molecule presents a significant challenge to traditional molecular dynamics due to its inherent nonlinearity, demanding a combined classical and quantum mechanical treatment for a complete understanding. Classical trajectories, while computationally efficient, fail to accurately capture the molecule’s full behavior as energy increases, quickly diverging from realistic representations of atomic motion. This breakdown highlights the importance of quantum mechanics, which accounts for the wave-like nature of particles and provides a more accurate description of energy levels and vibrational states. Specifically, exploring both approaches allows researchers to identify when classical simulations become inadequate and where quantum effects-such as tunneling and zero-point energy-become dominant, ultimately providing a more nuanced and reliable model of the molecule’s complex dynamics and its response to external stimuli.

The intricate dynamics of the potassium cyanide (KCN) molecule reveal that even seemingly simple systems can exhibit profoundly complex behaviors with significant consequences for their energy levels and responsiveness to external influences. Studies demonstrate that chaotic behavior emerges in KCN at surprisingly low excitation energies – around 145 cm-1 – a threshold where traditional linear models of molecular vibration break down. This sensitivity means that even minimal external stimuli can trigger unpredictable and far-reaching changes in the molecule’s vibrational state and overall energy distribution. Consequently, a thorough understanding of this inherent complexity is not merely academic; it is essential for accurately predicting and interpreting the molecule’s behavior in diverse chemical and physical environments, and for potentially controlling its response through targeted external interventions.

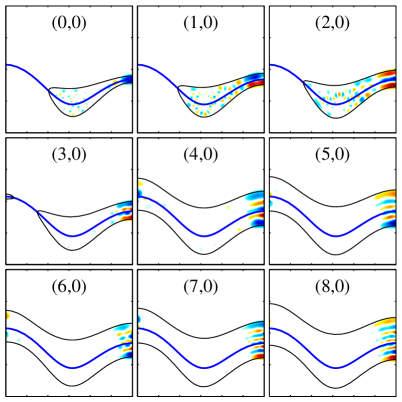

![Adiabatic eigenstates of KCN, visualized as probability densities across a <span class="katex-eq" data-katex-display="false"> [0, \pi] </span> rad by <span class="katex-eq" data-katex-display="false"> [4, 8] </span> a.u. plane, reveal harmonic oscillator states along the K-CN linear configuration at <span class="katex-eq" data-katex-display="false"> \theta = 0 </span>, with minimum energy paths indicated by a thick blue line and eigenenergies by a thin black line, as detailed in Table 2.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.06881v1/x2.png)

Mapping Chaos: The Language of Phase Space

The Poincaré Surface of Section is a technique used to analyze the qualitative behavior of dynamical systems, particularly those exhibiting chaotic motion, as demonstrated with the KCN molecule. This method involves examining the intersections of a trajectory in phase space with a chosen hypersurface. By plotting these intersection points, a two-dimensional representation of the system’s dynamics is created, effectively reducing the complexity of the higher-dimensional phase space. For the KCN molecule, the resulting patterns on the Poincaré section reveal intricate, non-repeating structures indicative of chaotic behavior, allowing researchers to visualize and quantify the sensitivity to initial conditions and the complex interplay of forces governing its molecular motion. The density and distribution of points on the section provide insights into the stability and nature of the chaotic trajectories.

The Poincaré-Birkhoff theorem establishes conditions under which a conservative system exhibits chaotic behavior. Specifically, it states that if a continuous family of area-preserving mappings on a surface contains an element with at least one stable and one unstable fixed point, then there exists an infinite sequence of points whose orbits are unbounded. This theorem fundamentally links the existence of hyperbolic fixed points to the emergence of chaotic dynamics, demonstrating that the breakdown of predictable, periodic orbits is not merely a consequence of complex interactions, but can be formally predicted under certain topological conditions. The theorem is typically applied to Hamiltonian systems and provides insight into phenomena such as the dynamics of celestial bodies and the behavior of particles in accelerators.

The Kolmogorov-Arnold-Moser (KAM) theorem addresses the stability of quasi-periodic orbits in dynamical systems that are “nearly integrable.” Integrable systems possess a sufficient number of conserved quantities to ensure completely regular orbits; however, most physical systems are perturbed from this ideal. The KAM theorem formally demonstrates that for small perturbations, a significant measure of the phase space retains quasi-periodic orbits, preventing a complete transition to chaos. Specifically, it states that tori in phase space corresponding to these quasi-periodic motions are not completely destroyed by small deviations from integrability, but rather deformed into smooth, elliptical shapes. This implies that even in systems exhibiting chaotic behavior, islands of stability-regions where quasi-periodic orbits persist-can exist, offering a detailed understanding of the structure of phase space and the transition from regular to chaotic dynamics.

Quantum Scars: Echoes of Classical Instability

The KCN molecule, when treated quantum mechanically, exhibits vibrational states significantly influenced by the chaotic nature of its classical potential energy surface. This influence is not a general disruption of quantum behavior, but rather a specific phenomenon termed ‘scarring’. Scarring occurs when certain quantum states concentrate their probability density along the unstable periodic orbits present in the corresponding classical system. These orbits, while unstable in classical mechanics, leave an imprint on the quantum wavefunction, resulting in enhanced probability density along their paths – effectively ‘scarring’ the phase space. This demonstrates a direct connection between the classical dynamics and the structure of specific quantum states within the molecule, and is observable through analysis of the wavefunction’s spatial distribution.

Scarring, in the context of quantum mechanics, refers to the concentration of the quantum probability density function along unstable periodic orbits present in the corresponding classical system. This phenomenon indicates that certain quantum states ‘remember’ the underlying classical dynamics, even though these orbits are unstable and do not exist as persistent trajectories in the classical phase space. The extent of this localization is quantified by examining the width of the probability density around these orbits; narrower distributions signify stronger scarring. This correspondence between classical unstable periodic orbits and the localization of quantum probability density provides a crucial link demonstrating how classical behavior can influence and be reflected in quantum systems, particularly in systems exhibiting chaotic dynamics.

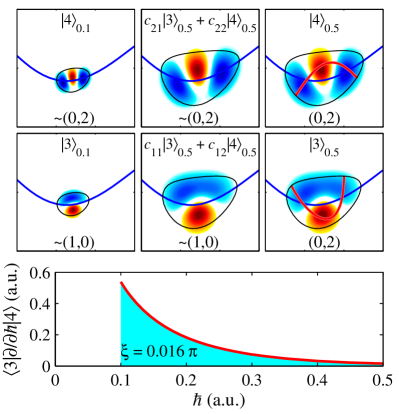

The Husimi and Wigner functions are quasiprobability distributions used to represent quantum states in phase space, facilitating the visualization and analysis of quantum scarring. While not true probability distributions due to the uncertainty principle, they allow researchers to map quantum wavefunctions onto a classical phase space (q, p) . The Husimi function, obtained by convolving the wavefunction with a Gaussian, provides a smoothed representation, highlighting the concentration of quantum probability along unstable periodic orbits indicative of scarring. Conversely, the Wigner function offers a more direct, albeit potentially negative-valued, representation of the quantum state, revealing interference effects and providing a finer-grained depiction of the scarring patterns. Analysis of these distributions allows for quantitative assessment of the correspondence between classical chaotic trajectories and the localization of quantum states in the KCN molecule.

Adiabatic and Diabatic States: Two Sides of Molecular Evolution

Adiabatic states represent a foundational concept in quantum dynamics, characterized by their smooth and continuous evolution as external parameters of a system are altered. This smoothness implies that the wavefunction of the system adjusts gradually to the changing parameters, maintaining a definite quantum number throughout the process. Mathematically, the adiabatic theorem states that if a perturbation is applied slowly enough, the system will remain in the instantaneous eigenstate of the Hamiltonian. The timescale for this ‘slowly enough’ condition is inversely proportional to the energy difference between the adiabatic state and its nearest excited state; larger energy gaps permit faster parameter changes while still maintaining adiabaticity. Understanding adiabatic states is crucial for analyzing molecular dynamics, particularly in scenarios involving potential energy surface crossings or non-radiative transitions, as they provide a framework for describing how a system avoids transitions between states during parameter variation.

Diabatic states represent an alternative description of a quantum system’s evolution, constructed as linear combinations of the adiabatic states. Unlike adiabatic states which maintain smoothness during parameter changes, diabatic states are not constrained by this requirement. This allows for a description where state vectors can undergo abrupt changes as system parameters are varied. Mathematically, if |\psi_i^a\rangle represents an adiabatic state, a diabatic state |\psi_i^d\rangle can be expressed as |\psi_i^d\rangle = \sum_j c_{ij} |\psi_j^a\rangle, where the coefficients c_{ij} define the linear transformation. This representation is particularly useful when analyzing non-adiabatic processes, such as transitions induced by strong perturbations, where the smoothness assumption of adiabatic states breaks down.

Quantum resonance in the KCN molecule arises from the interaction, or coupling, of vibrational modes, specifically impacting the energy level structure. The 1:2 resonance, a prominent example, describes a coupling where one vibrational mode’s frequency is approximately half that of another. This interaction leads to the formation of ‘scars’ – specific wavefunctions that persist for extended periods due to constructive interference, deviating from the expected statistical distribution of energy levels. The resulting energy level structure exhibits complex patterns and non-random distributions, observable through spectroscopic analysis, and is not solely determined by the molecule’s symmetry or a simple harmonic approximation. \hbar \omega_1 \approx 2 \hbar \omega_2 represents the approximate relationship for the 1:2 resonance, where \omega_1 and \omega_2 are the angular frequencies of the coupled modes.

The Correlation Diagram: Bridging Quantum and Classical Realms

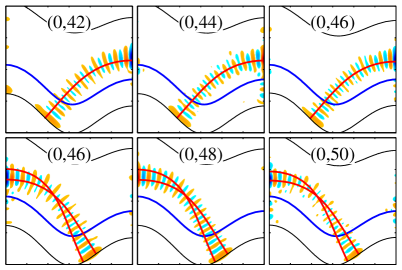

The correlation diagram offers a powerful method for dissecting the vibrational energy levels of molecular systems by deliberately altering a fundamental constant – Planck’s constant, typically explored between 0.10 and 3.00 atomic units. This systematic variation doesn’t simply adjust energy scales; it effectively interpolates between fully quantum and classically behaving systems. By observing how energy levels evolve across this range, researchers can discern the fingerprints of quantum phenomena, such as tunneling and zero-point energy, and pinpoint the onset of classical behavior. The resulting diagram visually maps the relationship between these quantum and classical regimes, revealing how molecular vibrations transition from being governed by discrete energy levels to continuous ones, and providing critical insight into the very nature of molecular motion.

Investigations utilizing the correlation diagram demonstrate that quantum effects profoundly reshape the energy level structure of molecular systems. Rather than a smooth, continuous distribution, energy levels exhibit distinct patterns, including the appearance of ‘scars’ – unusually high probabilities for specific quantum states corresponding to unstable classical trajectories. These scars aren’t random; they arise from the quantum wavefunctions constructively interfering along these classical paths, effectively ‘remembering’ the chaotic dynamics of the system. The spacing between energy levels deviates significantly from predictions based on purely classical mechanics, displaying characteristics like level repulsion and the emergence of statistical patterns that betray the underlying quantum nature of the molecule. This method allows researchers to observe how quantum mechanics fundamentally alters the expected energy landscape, revealing a complex interplay between order and chaos that governs molecular behavior and spectral features.

Investigations utilizing the correlation diagram reveal a nuanced relationship between classical and quantum behaviors within complex molecular systems. These analyses demonstrate that seemingly chaotic energy level structures are not entirely random, but instead exhibit patterns linked to specific quantum resonances, notably the 1:2 resonance where a vibrational mode oscillates twice as fast as another. This connection between order and chaos has significant implications for interpreting spectroscopic data, as the observed spectral lines directly reflect the underlying quantum energy levels. Furthermore, understanding this interplay is crucial for predicting chemical reactivity, since vibrational energy plays a key role in determining whether a molecular collision will lead to a chemical reaction; the precise arrangement of energy levels – shaped by both classical and quantum effects – can either facilitate or inhibit bond breaking and formation. The study therefore bridges the gap between macroscopic observations and the underlying quantum world, offering a powerful tool for controlling and predicting molecular behavior.

The study of KCN’s vibrational spectrum, as presented, demonstrates how complex behavior arises not from imposed design, but from the interplay of fundamental parameters. The transition from order to chaos, charted through correlation diagrams and varying the Planck constant, highlights this principle. It’s not a predetermined outcome, but an emergent property of the system itself. As Ludwig Wittgenstein observed, “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” Similarly, the observed dynamics reveal that the system’s behavior is constrained, yet surprisingly rich, within the boundaries of its physical laws – a world defined by its inherent rules, rather than external direction. The effect of the whole is not always evident from the parts; sometimes it’s better to observe than intervene.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The study of KCN, as presented, isn’t about finding control parameters, but about witnessing the inevitable blossoming of complexity. The correlation diagrams reveal a familiar story: order isn’t built into the molecule, it emerges from the interplay of simple potentials. To assume one could design a molecule to avoid this transition to chaos is to misunderstand the process entirely. Future work shouldn’t focus on suppressing these resonances, but on understanding how robustly such scarred states exist in larger, more complex systems. The persistence of these structures suggests they aren’t fragile artifacts, but fundamental features of the underlying dynamics.

The reliance on a single molecule, even one as conveniently simple as KCN, represents a limitation. The next logical step isn’t merely to examine larger molecules, but to explore the statistical properties of these vibrational landscapes across a range of chemical compositions. One anticipates a universal distribution of resonance strengths, a fingerprint of the inherent unpredictability. Identifying the boundaries of this statistical behavior – where the system slips entirely into featureless chaos – will be more informative than chasing specific eigenstates.

Ultimately, the significance lies not in predicting individual vibrational frequencies, but in recognizing the limits of predictability itself. System structure is stronger than individual control. The Planck constant serves as a tuning knob, certainly, but it reveals a pre-existing tendency towards complexity, not its origin. The challenge isn’t to tame the chaos, but to map its topography and accept its inevitability.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.06881.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Solo Leveling: Ranking the 6 Most Powerful Characters in the Jeju Island Arc

- How to Unlock the Mines in Cookie Run: Kingdom

- YAPYAP Spell List

- Top 8 UFC 5 Perks Every Fighter Should Use

- Bitcoin Frenzy: The Presales That Will Make You Richer Than Your Ex’s New Partner! 💸

- How to Build Muscle in Half Sword

- Bitcoin’s Big Oopsie: Is It Time to Panic Sell? 🚨💸

- Gears of War: E-Day Returning Weapon Wish List

- How to Find & Evolve Cleffa in Pokemon Legends Z-A

- Most Underrated Loot Spots On Dam Battlegrounds In ARC Raiders

2026-02-09 22:23