Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers are leveraging artificial intelligence to dramatically speed up the development of hardware for securing data against future quantum threats.

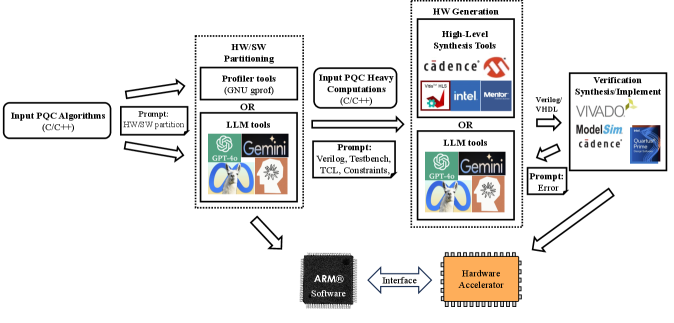

This work demonstrates the use of large language models to accelerate FPGA-based hardware acceleration for post-quantum cryptographic algorithms, achieving performance competitive with traditional high-level synthesis methods.

The increasing threat of quantum computing necessitates a shift to post-quantum cryptography (PQC), yet implementing these complex algorithms efficiently on hardware remains a significant challenge. This work, ‘Accelerating Post-Quantum Cryptography via LLM-Driven Hardware-Software Co-Design’, explores a novel approach leveraging Large Language Models (LLMs) to accelerate the design of FPGA-based accelerators for PQC, specifically focusing on the FALCON signature scheme. We demonstrate that LLM-guided hardware-software co-design can achieve up to 2.6x speedup in kernel execution compared to conventional High-Level Synthesis, albeit with associated trade-offs in resource utilization. Could this LLM-driven paradigm unlock a new era of rapid and adaptive PQC deployment on FPGAs, mitigating the risks posed by emerging quantum threats?

The Inevitable Quantum Reckoning

Modern digital security fundamentally depends on the difficulty certain mathematical problems pose for computers. Specifically, algorithms like RSA and Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) hinge on the computational hardness of factoring large numbers and solving the discrete logarithm problem, respectively. These problems are considered ‘hard’ because the time required to solve them increases exponentially with the size of the number, rendering brute-force attacks impractical with current classical computers. However, Shor’s algorithm, a quantum algorithm developed by Peter Shor in 1994, dramatically alters this landscape. This algorithm can efficiently solve both the factoring and discrete logarithm problems, effectively breaking the cryptographic systems that rely on their presumed intractability. While large-scale, fault-tolerant quantum computers capable of running Shor’s algorithm do not yet exist, the theoretical vulnerability underscores a critical need to proactively develop and deploy cryptographic methods resistant to quantum attacks.

The anticipated arrival of scalable quantum computers presents a fundamental challenge to modern digital security, demanding a proactive shift towards cryptographic systems that can withstand quantum attacks. Current public-key encryption methods, such as RSA and Elliptic Curve Cryptography, which underpin much of internet security, are based on mathematical problems considered intractable for classical computers, but are efficiently solvable by Shor’s algorithm running on a sufficiently powerful quantum computer. This vulnerability necessitates the development and implementation of Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC), a field focused on algorithms resistant to both classical and quantum attacks. The urgency stems not just from the theoretical threat, but also from the longevity of encrypted data – adversaries could store encrypted communications today and decrypt them once quantum computers become available. Consequently, researchers are actively investigating and standardizing new cryptographic approaches, including lattice-based cryptography, multivariate cryptography, code-based cryptography, and hash-based signatures, to ensure continued confidentiality and integrity in a post-quantum world, representing a significant undertaking to safeguard digital infrastructure.

While much attention focuses on the vulnerability of public-key cryptography to Shor’s Algorithm, Grover’s Algorithm presents a significant, though often understated, threat to symmetric key algorithms like AES. This quantum algorithm doesn’t break symmetric encryption in the same way, but it effectively halves the key length, meaning a 128-bit key becomes equivalent to a 64-bit key in terms of computational security. Consequently, a proactive shift towards larger key sizes – such as 256-bit AES – is crucial for maintaining adequate security margins in a post-quantum world. This necessitates comprehensive cryptographic updates across all systems currently relying on symmetric encryption, not merely as a preventative measure against future quantum computers, but as a pragmatic response to the accelerating progress in quantum computing capabilities and the diminishing assurance offered by existing key lengths. The widespread adoption of these larger key sizes and potentially new symmetric algorithms represents a critical, and often overlooked, component of the broader transition to Post-Quantum Cryptography.

NIST Steps In, and FALCON Takes Flight

In 2016, the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) launched a multi-year standardization process to identify and select Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC) algorithms resilient to attacks from quantum computers. This initiative, prompted by the increasing threat posed by quantum computing to currently deployed public-key cryptography, involved a public call for submissions, followed by rigorous evaluation rounds. Candidate algorithms were assessed based on their security, performance characteristics – including key and signature sizes, as well as encryption and decryption speeds – and implementation considerations. NIST’s evaluation framework encompassed both cryptanalytic attacks and side-channel analysis to ensure a comprehensive security assessment of each submission. The process culminated in the selection of several algorithms, announced in 2022 and 2023, intended to replace vulnerable cryptographic standards like RSA and ECC.

FALCON was selected as a PQC standard by NIST due to its performance characteristics, specifically its compact signature size – approximately 670 bytes – and efficient key generation and signing operations. Compared to other candidate algorithms, FALCON achieves a significantly smaller signature size without compromising security, which is crucial for bandwidth-constrained applications and efficient storage. This efficiency is achieved through the use of a carefully optimized implementation of lattice-based techniques, enabling faster computations and reduced resource consumption during cryptographic operations. The algorithm’s parameters were chosen to balance security against these performance gains, resulting in a practical solution for digital signatures in a post-quantum environment.

FALCON’s security is predicated on the computational difficulty of solving problems within lattice-based cryptography. Specifically, it utilizes the structure of N-th degree Truncated Polynomial Ring (NTRU) lattices. The NTRU problem involves finding a short vector in a lattice defined by these polynomial rings, a task considered computationally intractable for sufficiently large N and appropriate parameter selection. FALCON’s design leverages the presumed hardness of this problem to ensure the security of its digital signature scheme; successful forgery would require efficient solutions to the underlying NTRU problem, which currently remains beyond the capabilities of known algorithms.

FPGAs: A Hardware Lifeline for Post-Quantum Crypto

Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs) present a viable acceleration platform for cryptographic algorithms by exploiting both reconfigurability and inherent parallelism. Unlike CPUs and GPUs which are fixed in their architecture after manufacturing, FPGAs allow designers to customize the hardware to directly implement the specific operations of an algorithm. This customization enables a significant reduction in clock cycles per operation. Furthermore, FPGAs can execute multiple operations concurrently due to their architecture consisting of configurable logic blocks and interconnects, achieving true parallel processing. This capability is particularly advantageous for algorithms like FALCON which involve numerous independent calculations, leading to substantial performance gains compared to sequential execution on conventional processors.

Implementing FALCON on a Field-Programmable Gate Array (FPGA) requires converting the algorithm’s computational steps into a hardware description. This is achieved through two primary methodologies: Register Transfer Level (RTL) design and High-Level Synthesis (HLS). RTL design involves manually coding the algorithm’s data flow using hardware description languages like VHDL or Verilog, providing fine-grained control over the hardware implementation. Conversely, HLS allows designers to describe the algorithm in a higher-level language, such as C or C++, and then utilizes specialized tools to automatically generate the corresponding RTL code. The choice between RTL and HLS depends on factors such as design complexity, performance requirements, and development time; HLS generally offers faster development cycles, while RTL design can potentially yield higher performance through manual optimization.

FALCON’s performance benefits substantially from utilizing dedicated hardware resources within the FPGA architecture. Specifically, the algorithm’s computationally intensive modular arithmetic operations are accelerated by mapping them to DSP48E2 units. These units provide high-throughput multiplication and accumulation capabilities, directly addressing the core calculations within FALCON. Our implementation, leveraging this approach, demonstrated an average speedup of 1.782x when compared to a software-based baseline, indicating a significant improvement in throughput achieved through hardware acceleration of these critical operations.

LLMs: The Automation Wave Sweeping Through Hardware Design

The landscape of hardware design is undergoing a significant shift, with Large Language Models (LLMs) emerging as powerful tools for automation. Traditionally a labor-intensive process requiring specialized expertise in Hardware Description Languages (HDLs) like Verilog and VHDL, aspects of hardware creation are now being streamlined through LLM-driven approaches. These models demonstrate an ability to generate functional HDL code from high-level specifications, effectively bridging the gap between algorithmic design and physical implementation. Beyond simple generation, LLMs are being leveraged for optimization tasks, exploring design spaces and identifying configurations that improve performance and efficiency. This automation not only accelerates the hardware development lifecycle but also lowers the barrier to entry, allowing researchers and engineers to rapidly prototype and deploy complex digital circuits.

The automation of hardware design is significantly advanced through the application of large language models, which effectively translate abstract algorithmic descriptions directly into functional Verilog code. This approach bypasses traditional, manual hardware description, markedly accelerating the implementation process. Recent studies demonstrate the efficacy of this methodology; an LLM-driven design flow achieved a substantial 1.782x speedup when contrasted with a purely software baseline. While hardware synthesis using High-Level Synthesis (HLS) also provides acceleration, it achieved a comparatively smaller 1.15x speedup, suggesting that LLMs offer a compelling alternative for rapid hardware prototyping and optimization, particularly when minimizing time-to-implementation is paramount.

The integration of Large Language Models with hardware-software co-design and High-Level Synthesis (HLS) offers a powerful pathway for accelerating the development and optimization of Post-Quantum Cryptography (PQC) algorithms on Field-Programmable Gate Arrays (FPGAs). Recent studies demonstrate that leveraging LLMs for hardware design not only speeds up the prototyping process, achieving a 1.782x speedup over software baselines, but also yields tangible improvements in key performance indicators. Specifically, LLM-assisted designs exhibited a 6.99% reduction in power consumption when compared to designs generated solely through HLS. While this came at the cost of a 31.86% increase in Look-Up Table (LUT) and Flip-Flop (FF) utilization, the resulting performance gains were significant; for the critical modp_montymul operation, the LLM-generated design achieved a critical path of 4.805 ns, nearly halving the 9.646 ns observed in the HLS counterpart, suggesting a substantial advancement in hardware efficiency.

The pursuit of accelerated post-quantum cryptography via LLM-driven hardware-software co-design feels less like innovation and more like a predictable escalation. The article highlights performance gains with FPGA acceleration, but also acknowledges resource trade-offs. This mirrors a fundamental truth: everything optimized will one day be optimized back. Blaise Pascal observed, “The eloquence of a man never convinces so much as his sincerity.” Similarly, the allure of faster cryptography isn’t the speed itself, but the underlying promise of sustained security. The study demonstrates an alternative path to implementation, a compromise that survived deployment, but ultimately, it’s just another layer in the perpetual arms race against entropy. The elegance of LLM-assisted design doesn’t negate the inevitable: production will always find a way to break elegant theories.

What’s Next?

The automation of hardware design via Large Language Models presents a familiar allure – a promise of reduced development time and increased accessibility. The demonstrated co-design approach, while intriguing, merely shifts the complexity. The true bottlenecks will not reside in generating Verilog, but in verifying the resulting hardware, ensuring constant-time execution, and mitigating the subtle side-channel attacks that inevitably emerge from accelerated designs. It’s a classic case: replace one form of debugging with another, potentially more obscure, form.

The current focus on FPGA acceleration is, predictably, a stepping stone. The inevitable pursuit of ASIC implementations will reveal the limitations of LLM-generated designs when confronted with real-world manufacturing constraints and power budgets. The elegant diagrams produced by these models will, as always, collide with the messy reality of physical silicon. The question isn’t whether the approach can scale, but whether the resulting designs will be more maintainable than the hand-optimized solutions they aim to replace.

Ultimately, this work highlights a broader trend: the increasing reliance on automated tools to address increasingly complex security challenges. The field should anticipate a future where the speed of innovation in attack vectors outpaces the ability of automated defenses to adapt. The real innovation won’t be in generating faster hardware, but in developing robust, provably secure cryptographic primitives that minimize the need for acceleration in the first place.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.09410.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- How to Unlock the Mines in Cookie Run: Kingdom

- YAPYAP Spell List

- How to Build Muscle in Half Sword

- Bitcoin Frenzy: The Presales That Will Make You Richer Than Your Ex’s New Partner! 💸

- Gears of War: E-Day Returning Weapon Wish List

- Bitcoin’s Big Oopsie: Is It Time to Panic Sell? 🚨💸

- How to Find & Evolve Cleffa in Pokemon Legends Z-A

- How to Get Wild Anima in RuneScape: Dragonwilds

- The Saddest Deaths In Demon Slayer

- Most Underrated Loot Spots On Dam Battlegrounds In ARC Raiders

2026-02-11 13:02