Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers demonstrate a practical error-correction encoder for superconducting circuits, enhancing reliability in the face of manufacturing imperfections and faults.

A lightweight Reed-Muller code encoder improves error-free transmission probability for SFQ-to-CMOS interface circuits under process variation.

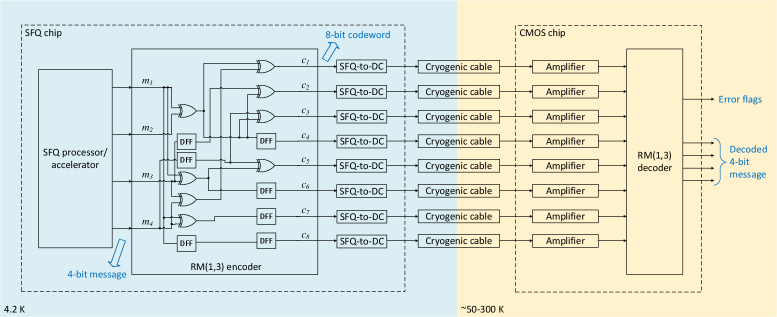

Reliable data transmission between cryogenic superconducting electronics and conventional semiconductor circuits is challenged by inherent error sources like flux trapping and process variations. This paper details the design and analysis of a hardware-efficient error-correction encoder, specifically a Reed-Muller code RM(1,3) encoder, implemented with superconducting SFQ logic as presented in ‘Reed-Muller Error-Correction Code Encoder for SFQ-to-CMOS Interface Circuits’. Simulations demonstrate a 6.7% improvement in error-free transmission probability under \pm20\% process variation, and near-complete error correction with lower variation, offering increased robustness against both systematic and random errors. Could this lightweight encoder pave the way for more resilient and scalable cryogenic digital systems?

The Inevitable Imperfections of Superconducting Logic

Superconducting circuits represent a paradigm shift in computational speed and energy efficiency, promising dramatically faster processing with minimal power consumption. However, this performance comes at a cost: an extraordinary sensitivity to even the smallest imperfections. Unlike conventional semiconductors which can tolerate a degree of manufacturing variability, superconducting devices – relying on the delicate quantum state of electron flow – are easily disrupted by defects at the nanoscale. These defects, arising from fabrication imperfections or material impurities, can introduce errors in logic operations and significantly degrade circuit performance. The challenge lies not in eliminating these defects entirely – an unrealistic goal given current manufacturing capabilities – but in designing systems robust enough to operate reliably despite their presence. This inherent fragility necessitates novel approaches to error mitigation and fault tolerance, moving beyond traditional methods ill-suited to the unique characteristics of superconducting computation.

Conventional error correction techniques, while robust in many digital systems, present significant challenges when applied to superconducting logic. These methods typically rely on redundancy – encoding information across multiple physical bits to detect and correct errors – which demands substantial overhead in terms of both computational resources and energy consumption. Superconducting circuits, designed for minimal energy dissipation and rapid processing, are particularly vulnerable to the performance penalties associated with this redundancy. The very architecture that promises efficiency can be undermined by the complex logic gates and increased wiring needed to implement traditional error correction codes, creating a trade-off between reliability and the inherent advantages of superconducting computation. Researchers are actively exploring novel error mitigation strategies tailored to the unique characteristics of these systems, seeking to maintain data integrity without sacrificing speed or energy efficiency.

The promise of superconducting logic hinges on maintaining data integrity despite the inevitable imperfections arising from fabrication processes. Unlike silicon-based chips where defects are relatively rare, superconducting circuits are exquisitely sensitive, meaning even minute flaws – variations in material deposition, unintended shorts, or open circuits – can corrupt computations. This heightened susceptibility necessitates novel approaches to error mitigation, as traditional error correction codes, while effective, often introduce significant overhead in terms of both computational resources and energy consumption – resources that superconducting systems aim to minimize. Researchers are therefore focused on developing error-resilient circuit designs and encoding schemes specifically tailored to the unique failure modes of superconducting technology, ensuring that computations remain accurate and reliable even in the presence of these unavoidable imperfections and paving the way for practical, fault-tolerant superconducting computers.

A Pragmatic Approach: The RM(1,3) Code

The RM(1,3) code functions as a linear block code, processing data in fixed-size blocks. Specifically, it encodes each k-bit message into an n-bit codeword, where for RM(1,3), k = 1 and n = 3. This encoding introduces redundancy, enabling the detection of up to n-1 errors and correction of up to t errors, where t = \lfloor \frac{n-k}{2} \rfloor. In the case of RM(1,3), this translates to single-bit error correction and the detection of up to two-bit errors. The linearity of the code ensures that the sum of any two valid codewords is also a valid codeword, simplifying both encoding and decoding processes.

The RM(1,3) code employs a Generator Matrix, G, to transform k-bit message vectors into n-bit codewords. For the RM(1,3) code, k=1 and n=3. This encoding process adds redundancy – two parity bits – to the original message bit. The parity bits are calculated based on the message bit and specific elements within the Generator Matrix. This redundancy allows the decoder to not only detect the presence of errors during transmission but also to pinpoint the location of a single-bit error, enabling its correction. The Generator Matrix is structured such that any single-bit error in the message will result in a non-zero syndrome, facilitating error detection and correction.

The RM(1,3) code presents a favorable trade-off between error correction performance and hardware requirements for Sequential Floating-gate Quantum (SFQ) logic applications. Its ability to correct single-bit errors is crucial for maintaining data integrity in SFQ circuits, which are susceptible to errors due to the inherent sensitivity of Josephson junctions. Critically, the relatively simple structure of the RM(1,3) code – requiring only the addition of redundant bits based on a defined Generator Matrix – translates to lower implementation complexity compared to more powerful error correcting codes. This minimized complexity is essential for practical SFQ circuit design, where minimizing gate count and circuit size is paramount to reducing power dissipation and maintaining operational speed.

Translating Theory into Practice: Circuit Implementation & Simulation

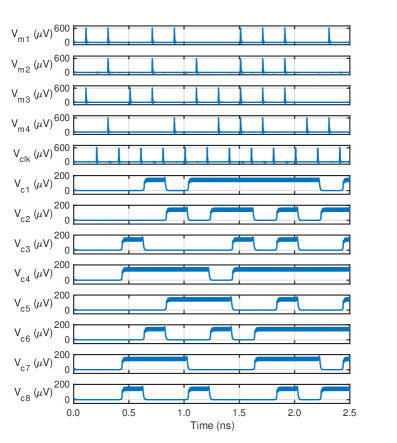

The RM(1,3) encoder’s circuit implementation relies on fundamental digital logic components for data handling and timing control. Specifically, XOR gates perform the bitwise exclusive OR operations necessary for generating the redundant bits, while D Flip-Flops are employed to synchronize data transitions with the system clock. The arrangement of these components enables the encoding of input data into the RM(1,3) codeword, creating parity for error detection. The D Flip-Flops ensure that data is reliably captured and held at the appropriate clock edges, preventing race conditions and maintaining data integrity throughout the encoding process. The number of XOR gates and D Flip-Flops directly correlates with the data width of the input signal being encoded.

The Clock Distribution Network (CDN) is a fundamental component for delivering the clock signal with minimal skew and jitter to all parts of the RM(1,3) decoder circuit, which is critical for maintaining timing margins and ensuring correct operation at high frequencies. Coupled with the CDN, the Single Flux Quantum (SFQ) Splitter allows for the parallel processing of data streams; it replicates the clock signal to drive multiple decoding stages concurrently, significantly improving throughput and reducing latency. Without efficient clock distribution and parallelization facilitated by the SFQ Splitter, the decoding process would be severely bottlenecked by serial data processing and clock signal propagation delays.

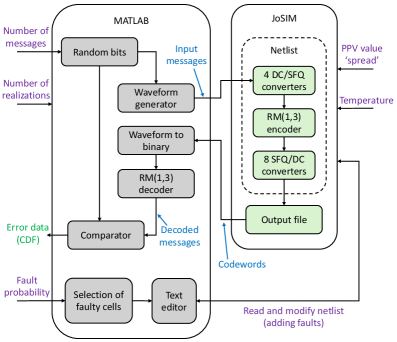

Circuit-level simulations employing JoSIM and SuperTools/ColdFlux are critical for validating the RM(1,3) code’s implementation, as they allow for detailed analysis of signal propagation, timing characteristics, and power consumption at the transistor level. These simulations verify that the logical design translates correctly into a functional circuit, identifying potential issues such as gate delays, signal integrity problems, and incorrect state transitions. By modeling the circuit’s behavior under various conditions – including process, voltage, and temperature (PVT) variations – these tools ensure robust performance and compliance with specified design constraints before physical fabrication. The simulations provide quantitative data on key performance indicators, including error rates and latency, enabling thorough evaluation of the code’s functionality and efficiency.

MATLAB serves as the central automation tool for post-simulation data acquisition and analysis within the RM(1,3) code verification flow. Specifically, MATLAB scripts are implemented to parse the output files generated by circuit simulations conducted in JoSIM and SuperTools/ColdFlux. These scripts automatically extract key performance metrics such as bit error rates, latency, and power consumption. This automated data collection eliminates the need for manual parsing, significantly reducing verification time and the potential for human error, and allows for efficient statistical analysis of simulation results to confirm code functionality and identify potential design weaknesses.

The Inevitable Reality: Robustness Under Imperfect Conditions

Investigations utilizing circuit simulations reveal the robust error-correcting capabilities of the RM(1,3) code when confronted with Open Circuit Faults – a prevalent issue arising during the fabrication process of integrated circuits. These faults, which represent broken connections within the circuit, can lead to signal failures and system malfunctions; however, the RM(1,3) code effectively detects and corrects these errors, ensuring reliable data transmission. The simulations model the impact of these faults on signal integrity and demonstrate the code’s ability to reconstruct the original information despite the presence of these defects, thereby enhancing the overall system resilience and yield during manufacturing. This correction mechanism is crucial for building dependable cryogenic circuits where identifying and mitigating fabrication flaws is particularly challenging.

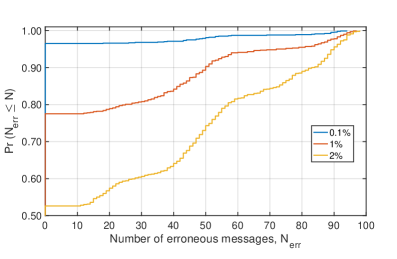

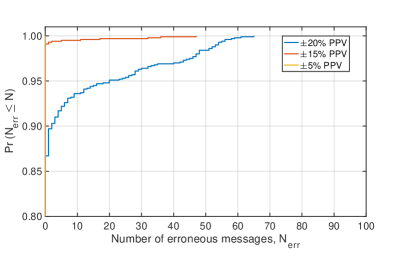

Evaluating the resilience of the RM(1,3) code under realistic manufacturing conditions required a thorough assessment of its performance with Process Parameter Variations (PPV). This involved simulating the code’s behavior across a range of deviations in key fabrication parameters, mirroring the inherent tolerances encountered in actual chip production. Results demonstrate a strong correlation between the degree of process variation and error-free transmission probability; with ±15% PPV, the code achieves 99.1% reliability, rising to 100% under tighter ±5% variations. Crucially, the RM(1,3) encoder significantly outperforms a comparable design lacking error correction, achieving an 86.7% probability of transmitting 100 messages without errors even with ±20% PPV – highlighting its ability to maintain functional integrity despite manufacturing imperfections and ensuring dependable operation in real-world applications.

Reliable communication between superconducting circuits and standard digital electronics necessitates specialized interface components, namely the Single Flux Quantum-to-DC Converter and the Single Flux Quantum-to-CMOS Interface. These circuits translate the information encoded in single-flux-quantum pulses into voltages and currents compatible with conventional CMOS technology. Rigorous testing of these interfaces using the error-corrected signals generated by the RM(1,3) code is paramount; it validates the entire system’s ability to maintain data integrity during the transition between the cryogenic superconducting domain and room-temperature electronics. Successful operation confirms that error correction not only safeguards data within the superconducting processor but also extends that protection to the crucial external communication channels, ensuring a robust and dependable hybrid computing architecture.

A critical aspect of the RM(1,3) code’s functionality lies in its ability to reliably differentiate between valid and corrupted data, a characteristic rigorously confirmed through Hamming Distance analysis. This metric quantifies the number of differing bits between codewords; a larger minimum Hamming Distance indicates a greater capacity to detect and correct errors. The study demonstrates that the RM(1,3) code generates codewords with sufficient separation-ensuring that even with the introduction of fabrication defects or process variations, the receiver can accurately distinguish a correct codeword from an erroneous one. This robust distinction is fundamental to the code’s error-correction capability, allowing it to identify and rectify single-bit errors, thereby maintaining data integrity throughout the system and guaranteeing dependable operation even under challenging conditions.

Evaluations demonstrate the resilience of the RM(1,3) encoder in the face of manufacturing uncertainties; under process variations of ±20%, the encoder successfully transmits 100 messages without error 86.7% of the time. This performance represents a significant improvement over a comparable design lacking error correction, highlighting the encoder’s ability to maintain data integrity despite fluctuations inherent in fabrication processes. The enhanced reliability is achieved through robust coding, allowing the system to overcome subtle deviations in component values and maintain accurate communication even when operating near the limits of manufacturing tolerances, suggesting a practical pathway toward dependable superconducting digital systems.

Evaluations reveal a high degree of resilience in the RM(1,3) code against typical manufacturing uncertainties; under process parameter variations (PPV) of ±15%, the system achieves an impressive 99.1% probability of error-free data transmission. Remarkably, this performance climbs to 100% accuracy when PPV is reduced to ±5%, demonstrating the code’s ability to maintain data integrity even with tight manufacturing tolerances. This level of robustness is critical for reliable operation in real-world applications, where subtle variations in fabrication are inevitable, and signifies a substantial improvement over designs lacking error correction capabilities.

Practical implementation of the RM(1,3) error-correcting encoder demonstrates a remarkably compact footprint and efficient power consumption. The circuit occupies a layout area of just 0.193 mm², indicating a high degree of integration and potential for use in space-constrained applications. Crucially, the encoder operates with a power dissipation of only 101.5 μW, signifying a low-energy design that minimizes heat generation and extends operational lifespan-characteristics vital for cryogenic superconducting systems and beyond. These metrics confirm the RM(1,3) code isn’t merely a theoretical construct, but a viable solution for robust data transmission with acceptable resource demands.

The pursuit of fault tolerance, as demonstrated by this Reed-Muller encoder for SFQ circuits, invariably introduces new layers of complexity. The study attempts to mitigate process variation, a predictably unpredictable force. It’s a temporary reprieve, a delay of the inevitable. Jean-Jacques Rousseau observed, “Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains.” Similarly, every elegant error-correction scheme becomes a new constraint, a shackle on future modifications. The system functions, yes, but at the cost of increased fragility in the face of different failures. The architecture shifts from a solution to a problem waiting to happen, a lesson repeated across every generation of circuit design.

What’s Next?

The presented encoding scheme, while demonstrating a marginal improvement in error resilience, feels…familiar. It’s a meticulously crafted solution to a problem that, inevitably, will become far more Byzantine. One suspects that as SFQ circuits scale – and they always promise to scale – the underlying process variations won’t remain so neatly characterized. They’ll call it ‘quantum fluctuations’ and request more funding. The elegance of Reed-Muller codes, initially conceived for simpler error models, will be strained. What began as a clever optimization will become a brittle layer in a stack of increasingly desperate workarounds.

The true challenge isn’t simply correcting for static process variations, but adapting to dynamic failures. SFQ circuits operate in a cryogenic environment – an environment not known for its stability. The inevitable thermal cycling and microscopic mechanical stresses will introduce failure modes not captured by current simulations. It is a reasonable expectation that the error characteristics will shift over time, rendering even the most carefully designed code obsolete. The documentation, naturally, will lie again.

One imagines a future where this lightweight encoder is augmented by layers of machine learning – ‘AI-powered fault tolerance’ – masking increasingly complex and unpredictable errors. This will, of course, introduce a new class of failures – the inscrutable, uncorrectable errors arising from the neural network itself. It’s a pattern. The system, once a simple bash script, will become an unmaintainable monolith, and the cycle will repeat. Tech debt is just emotional debt with commits, after all.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.11140.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- How to Build Muscle in Half Sword

- YAPYAP Spell List

- Bitcoin Frenzy: The Presales That Will Make You Richer Than Your Ex’s New Partner! 💸

- How to Unlock the Mines in Cookie Run: Kingdom

- Bitcoin’s Big Oopsie: Is It Time to Panic Sell? 🚨💸

- Epic Pokemon Creations in Spore That Will Blow Your Mind!

- Top 8 UFC 5 Perks Every Fighter Should Use

- How to Get Wild Anima in RuneScape: Dragonwilds

- Gears of War: E-Day Returning Weapon Wish List

- How to Find & Evolve Cleffa in Pokemon Legends Z-A

2026-02-12 07:57