Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have developed a novel analytical solution for modeling the nucleon-nucleon interaction, offering a powerful alternative to computationally intensive methods in femtoscopic studies.

This work presents an analytical solution within a square-well potential framework to explore the low-momentum behavior of the strong interaction and its implications for hadronic collisions.

Interpreting short-range correlations in high-energy collisions requires a detailed understanding of the strong nuclear force, yet accurate analytical treatments are often computationally demanding. This paper, ‘Strong potential in a box for applications to femtoscopy’, presents an analytical solution to the nucleon-nucleon interaction using a square-well potential, providing a flexible framework for femtoscopic analyses. The resulting pair wave function, incorporating multiple partial waves and Coulomb effects, accurately reproduces numerical calculations-particularly for realistic source sizes-and reveals limitations in commonly used asymptotic approximations. Could this approach offer a practical pathway to refine our understanding of the low-momentum behavior of the strong force and improve the precision of femtoscopic measurements?

The Strong Interaction: A Foundation for Understanding Matter

The strong interaction, a fundamental force of nature, dictates the behavior of nucleons – protons and neutrons – and is therefore central to understanding the structure of atomic nuclei and the processes powering stars. This force overcomes the electrostatic repulsion between protons, binding them together within the nucleus and enabling the formation of all elements heavier than hydrogen. Without the strong interaction, stable nuclei wouldn’t exist, and the universe as we know it would be dramatically different. Its influence extends beyond nuclear physics, playing a critical role in astrophysical phenomena like supernovae, neutron star formation, and the synthesis of elements in stellar interiors. Precisely characterizing this interaction is thus paramount, not only for unraveling the mysteries of matter at its most fundamental level, but also for accurately modeling the cosmos and the energetic events that shape it.

Although Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD) stands as the established theory describing the strong force, a direct calculation of nucleon-nucleon interactions from its fundamental principles proves remarkably difficult. This isn’t a failure of the theory itself, but a consequence of its inherent complexity; QCD equations become intractable when applied to systems as large as nucleons, due to the strong coupling of quarks and gluons. Consequently, physicists rely on effective models – approximations that simplify the calculations while retaining essential physics – to understand how nucleons interact. These models often incorporate empirical parameters, adjusted to match experimental data, which allows for predictions but limits the purely theoretical predictive power of QCD in this domain. Overcoming this computational hurdle remains a central challenge in nuclear physics, driving the development of increasingly sophisticated techniques like lattice QCD and chiral effective field theory to bridge the gap between fundamental theory and observable phenomena.

Historically, modeling the strong interaction between nucleons – protons and neutrons – has presented a persistent challenge, leading to reliance on approximations and the incorporation of empirical parameters. These parameters, adjusted to fit experimental data, allow physicists to describe nucleon-nucleon interactions, but often at the cost of genuine predictive capability. While successful in reproducing known phenomena, these traditional approaches struggle to accurately forecast interactions under novel conditions, such as those found in extreme astrophysical environments or within exotic nuclei. The dependence on fitted parameters suggests an incomplete theoretical understanding; a truly fundamental theory should, in principle, predict these interactions without the need for calibration against observation. This limitation motivates ongoing research into more robust and ab initio methods, aiming to derive nucleon-nucleon forces directly from the underlying principles of Quantum Chromodynamics and reduce the reliance on phenomenological inputs.

Probing the Interaction at Femtometer Scale: The Power of Femtoscopy

Femtoscopy, also known as identical-particle interferometry, relies on measuring correlations in the distribution of identical particles produced in high-energy collisions. These correlations arise because identical fermions, governed by Bose-Einstein statistics, exhibit interference effects dependent on the separation in space and time between their emission points. By analyzing the magnitude of this interference as a function of separation, researchers can reconstruct the dimensions – typically on the scale of 10^{-{15}} meters (a femtometer) – of the region where the particles were created. This reconstructed source size provides insights into the dynamics of the collision, including the temperature, density, and lifetime of the strongly interacting matter formed, and allows for the study of collective effects and the equation of state.

Femtoscopy directly leverages the principles of Hanbury-Brown-Twiss (HBT) interferometry, originally developed in astronomy to measure the angular diameter of stars. HBT interferometry relies on detecting correlations in the arrival times of identical bosons – or the coherence of identical fermions – to determine the size of the emitting source. Adapting this to high-energy particle collisions, femtoscopy analyzes the correlations of identical particles produced in these events. The degree of correlation is inversely proportional to the source size; smaller sources exhibit stronger correlations. This allows researchers to map the space-time characteristics of particle production regions in high-energy interactions, effectively probing the dynamics at \sim 10^{-{15}} meters (femtometers).

Accurate interpretation of two-particle correlation data in femtoscopy necessitates detailed modeling of final-state interactions (FSI). These interactions, arising from the strong and electromagnetic forces, can modify the observed pair wave function and distort the reconstructed source geometry. Specifically, Coulomb interactions are significant for identical charged particles, leading to an outward scattering effect that must be accounted for in the analysis. Furthermore, the underlying pair wave function, typically assumed to be Gaussian, may require modification to incorporate effects from the emission process and the source’s non-trivial shape. Ignoring or mismodeling these FSI and pair wave function characteristics introduces systematic errors in the determination of the source size and lifetime, potentially leading to incorrect inferences about the particle-emitting region and the dynamics of the collision.

Modeling the Pair Wave Function: From Theory to Precision

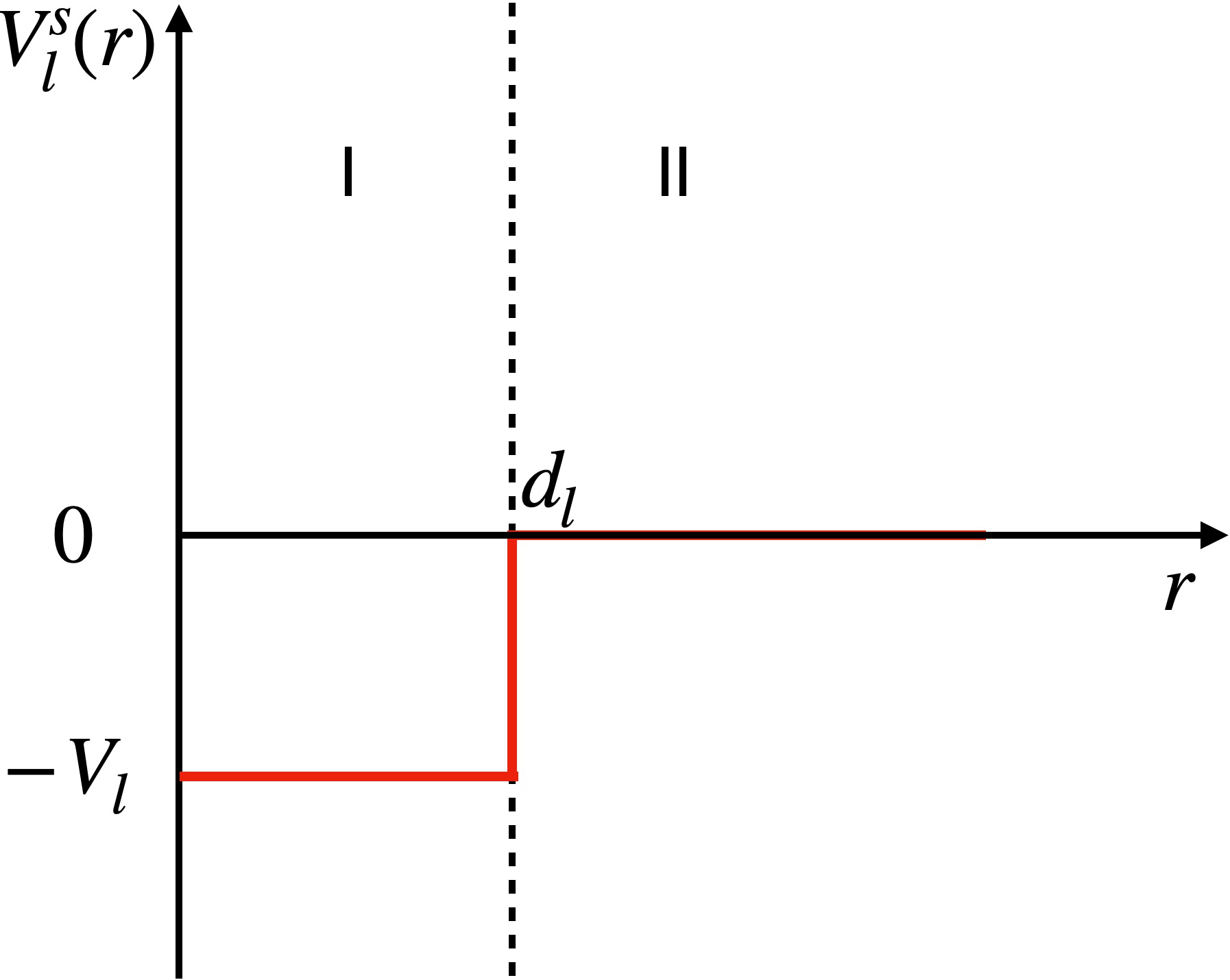

The time-independent Schrödinger equation, H\Psi = E\Psi, serves as the fundamental equation for determining the pair wave function, Ψ, which describes the quantum state of two interacting particles. However, obtaining analytical, closed-form solutions to this equation is generally intractable due to the complexity of the two-body potential. The nucleon-nucleon interaction, in particular, lacks a simple mathematical form. Consequently, approximations are necessary to make the Schrödinger equation solvable. These approximations often involve simplifying the potential – such as using parameterized forms like the square-well potential – or employing numerical methods to obtain approximate solutions. The validity of these approximations is then assessed by comparison with experimental data or more sophisticated theoretical calculations.

Modeling the nucleon-nucleon interaction necessitates the use of potential models due to the intractability of exact solutions to the Schrödinger equation. The simplest of these is the Square-Well Potential, providing a basic, though limited, representation. More accurate descriptions are achieved through phenomenological potentials, which are empirically determined and fitted to experimental scattering data. Commonly used examples include Nijm93, Reid93, and Argonne v18 potentials. These potentials differ in their mathematical form and the number of parameters used to describe the interaction, leading to varying degrees of accuracy in predicting nucleon-nucleon scattering and bound-state properties. The complexity of these potentials reflects the intricate nature of the strong nuclear force and the need for precise modeling to understand nuclear structure and reactions.

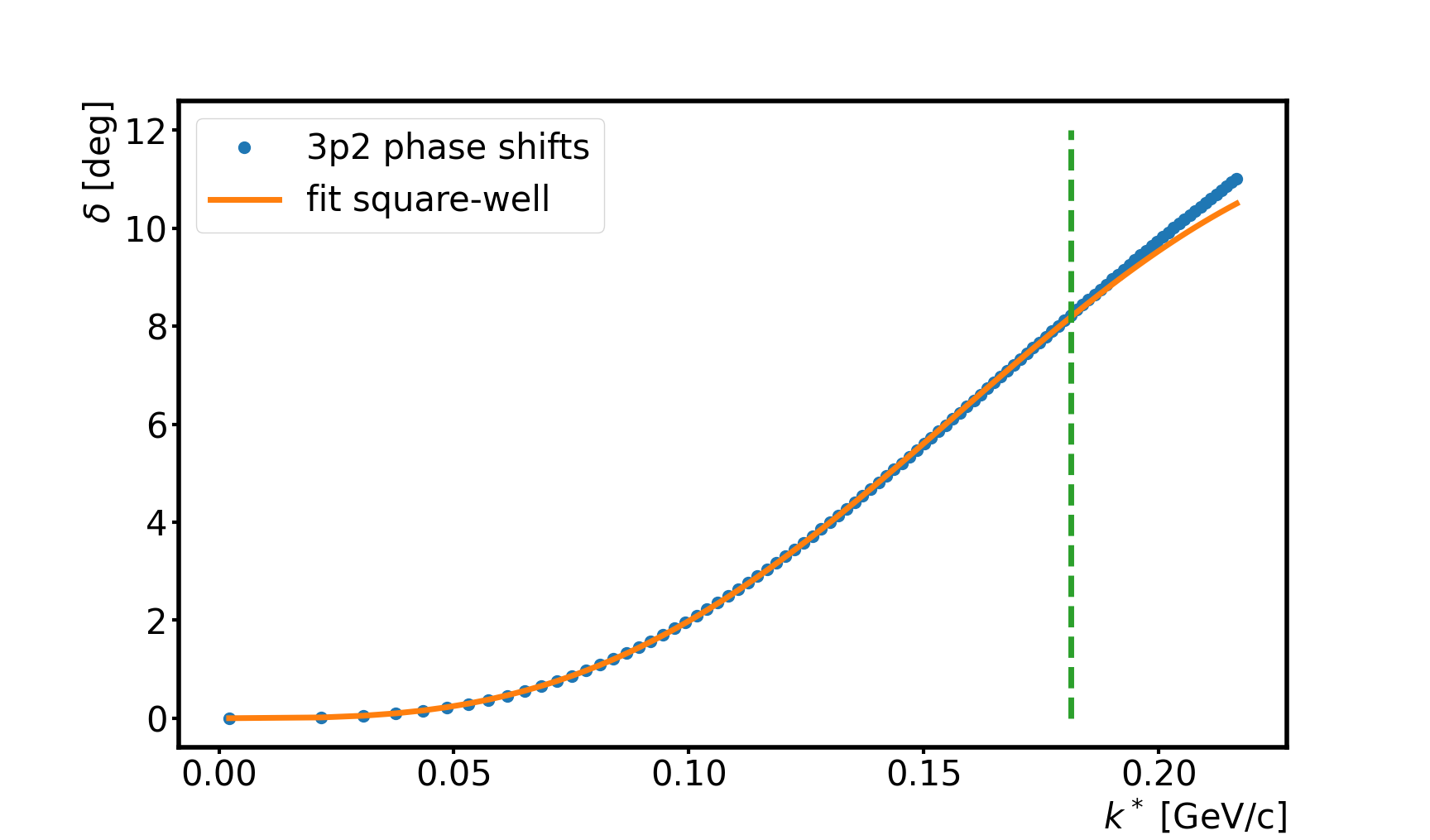

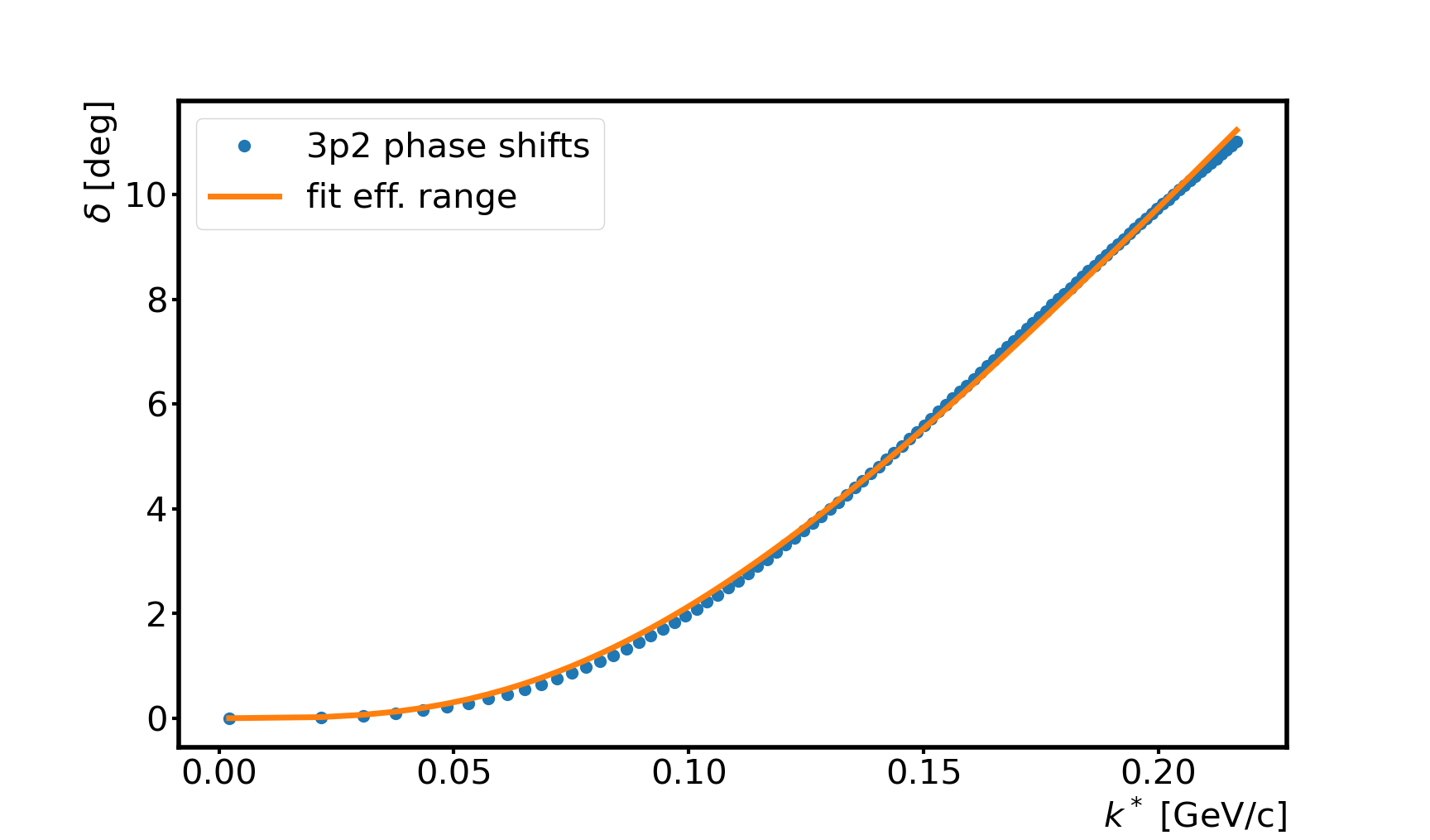

Enhancements to nucleon-nucleon potential models involve accounting for the Coulomb interaction between protons and employing Effective Range Parameterization (ERP). The Coulomb force, while weaker than the strong nuclear force, is significant at short distances and must be included for accurate calculations, particularly in proton-proton scattering. ERP provides a systematic way to represent the scattering amplitude near threshold using only a few parameters: the scattering length, the effective range, and the shape parameter. These parameters directly relate to the potential’s properties and allow for a more concise and physically meaningful representation of the interaction, improving the predictive power of the model and enabling comparisons with experimental data across a wider energy range.

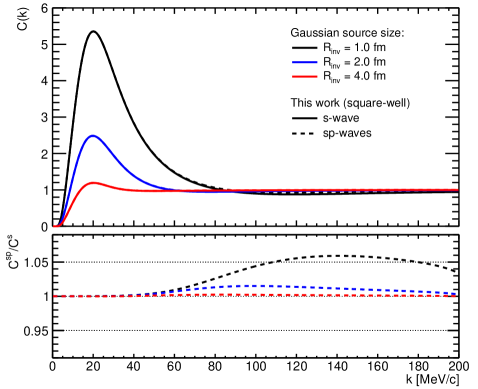

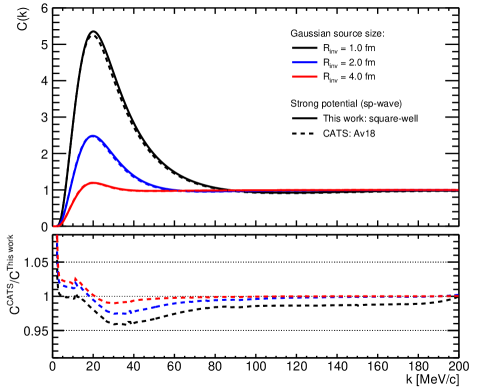

Calculations employing a square-well potential to model the pair wave function exhibit a high degree of correlation with more complex numerical calculations, showing discrepancies of less than 4% when the effective range, R_{eff}, is set to 1 fm. This level of agreement validates the utility of simplified potential models for investigating the short-range characteristics of the strong nuclear force. Accurate modeling of this short-range behavior is particularly important for the interpretation of femtoscopic measurements, which rely on understanding the spatial correlations of particle pairs produced in high-energy collisions and are sensitive to the range of the strong interaction.

Validating the Models: Experimental Insights from Colliders

Femtoscopic measurements, conducted at high-energy colliders like the Relativistic Heavy-Ion Collider (RHIC), the Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS), and the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), offer a unique window into the strong nuclear force. These experiments don’t directly observe the force itself, but instead analyze the correlations between identical particles – such as pions or kaons – emitted from the same point in space-time during heavy-ion collisions. By meticulously measuring these correlations at incredibly short distances – on the scale of femtometers, hence the name “femtoscopy” – physicists can reconstruct the spatial size and geometry of the particle-emitting source. This data then serves as critical validation for theoretical models attempting to describe the strong interaction potential between nucleons, effectively testing whether the models accurately predict the observed particle correlations and the properties of the dense matter created in these collisions.

Researchers leverage the power of high-energy collisions to rigorously test theoretical models of the strong nuclear force by analyzing particle correlations. Specifically, experiments at facilities like the Relativistic Heavy-Ion Collider and the Large Hadron Collider measure how often identical particles, such as pions or kaons, appear close together in space and time. These measurements are then distilled into correlation functions, mathematical representations of these particle pairings. The accuracy of potential models describing the nuclear interaction is then assessed by comparing their predictions – calculated using the Koonin-Pratt formula – with these experimentally derived correlation functions. Discrepancies reveal areas where the theoretical understanding of the strong force needs refinement, while strong agreement validates the models and builds confidence in their ability to describe matter under extreme conditions.

Investigations at facilities like the Relativistic Heavy-Ion Collider and the Large Hadron Collider don’t merely observe particle production; they actively refine the theoretical frameworks used to describe it. By meticulously measuring correlations between identical particles, these experiments effectively ‘tune’ the parameters within potential models-mathematical representations of the strong force governing interactions between quarks and gluons. The precision of these measurements allows physicists to discern the subtle ways in which the strong interaction influences not just the number of particles created, but also their momentum distributions and spatial correlations. Consequently, the resulting constraints on model parameters offer increasingly accurate depictions of the fundamental forces at play within extreme conditions, furthering understanding of matter at its most basic level and informing studies of everything from the interiors of neutron stars to the early universe.

The refined comprehension of how nucleons – protons and neutrons – interact extends far beyond the scope of heavy-ion collision experiments. Precise models of the strong nuclear force, validated by these collisions, are fundamental to understanding the structure and stability of atomic nuclei, impacting fields like nuclear physics and informing calculations of nuclear reaction rates in stars-a crucial component of astrophysical modeling. Furthermore, these insights are essential for predicting the behavior of matter under extreme conditions, such as those found in neutron stars or during the very early universe, where densities far exceed anything achievable on Earth. The ability to accurately describe nucleon-nucleon interactions at these densities is pivotal for constructing realistic equations of state for these exotic states of matter, ultimately deepening the understanding of matter’s fundamental properties and its evolution throughout the cosmos.

The pursuit of analytical solutions, as demonstrated in this study of nucleon-nucleon interactions, mirrors a fundamental desire for parsimony. The work elegantly bypasses computational complexity, favoring instead a direct, mathematical description of the strong force-a principle echoed by Bertrand Russell, who once stated, “The point of the world is that it has no point.” This resonates with the paper’s focus on distilling the essence of the interaction – a ‘square-well potential’ serving as a simplified, yet insightful, representation of a profoundly complex phenomenon. Clarity, in this instance, isn’t merely a stylistic preference, but the minimum viable kindness offered to understanding.

The Road Ahead

The persistence of analytical solutions in a field increasingly dominated by computation is not merely nostalgia. It suggests a desire-perhaps a belated one-to understand why things happen, not simply to record that they do. This work, by returning to a deceptively simple square-well potential, offers a foothold against the creeping complexity of fully realistic models. The true test, of course, lies in bridging the gap between this streamlined approach and the messiness of actual hadronic collisions.

One might suspect the limitations will quickly become apparent. The strong interaction, after all, rarely respects the neat boundaries of a potential well. But therein lies an opportunity. Identifying where and how this model breaks down will be far more instructive than any number of successful fits. It forces a reckoning with the physics lost in the simplification-a useful exercise in any field prone to over-engineering. They called it a framework to hide the panic, but sometimes a clear view of the bones is all that’s needed.

The future likely involves refining the treatment of boundary conditions and exploring the sensitivity of femtoscopic observables to subtle deviations from the idealized potential. Perhaps, too, it will encourage a broader reassessment of the assumptions embedded in more complex calculations. Simplicity, after all, is not a weakness. It is a challenge-a demand for greater understanding.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.11027.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- How to Build Muscle in Half Sword

- YAPYAP Spell List

- Epic Pokemon Creations in Spore That Will Blow Your Mind!

- Top 8 UFC 5 Perks Every Fighter Should Use

- How to Get Wild Anima in RuneScape: Dragonwilds

- Bitcoin Frenzy: The Presales That Will Make You Richer Than Your Ex’s New Partner! 💸

- Bitcoin’s Big Oopsie: Is It Time to Panic Sell? 🚨💸

- One Piece Chapter 1174 Preview: Luffy And Loki Vs Imu

- Gears of War: E-Day Returning Weapon Wish List

- All Pistols in Battlefield 6

2026-02-13 05:30