Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers demonstrate that encoding data with composite DNA ‘letters’ doesn’t sacrifice reliability and can leverage existing error correction techniques to overcome realistic storage errors.

The study shows that Low-Density Parity-Check codes effectively mitigate substitution, insertion, and deletion errors in high-density DNA data storage systems using multinomial modulation.

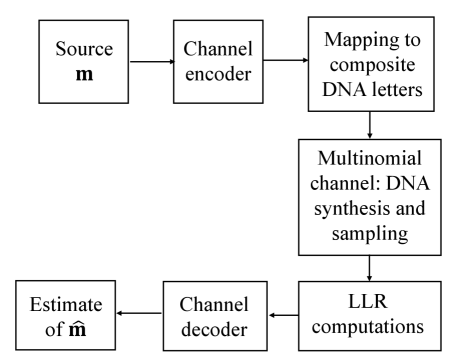

The escalating demands of the digital age challenge conventional data storage paradigms, prompting exploration of high-density alternatives. This is addressed in ‘Robust Composite DNA Storage under Sampling Randomness, Substitution, and Insertion-Deletion Errors’, which investigates increasing storage capacity through composite DNA letters-mixtures of nucleotides-and a corresponding error correction framework. We demonstrate that existing low-density parity-check (LDPC) codes can effectively mitigate realistic errors-including sampling noise, substitutions, and insertions/deletions-when coupled with a multinomial channel model and carefully designed constellation update rules. Could this approach unlock truly scalable and durable long-term data archiving using synthetic biology?

The Looming Data Density Crisis and DNA’s Potential

The relentless growth of the digital universe is rapidly pushing the boundaries of conventional data storage technologies. Current methods, relying on magnetic and solid-state drives, are encountering physical limitations in how much data can be packed into a given space – a challenge known as density. Beyond this, these mediums suffer from relatively short lifespans, requiring costly and energy-intensive data migration as storage degrades. Furthermore, the operation of massive data centers contributes significantly to global energy consumption, raising sustainability concerns. These converging pressures – dwindling density, limited longevity, and escalating energy demands – are driving a search for fundamentally new storage mediums capable of overcoming these inherent constraints and securing the future of information preservation.

The potential of deoxyribonucleic acid, or DNA, as a data storage medium stems from its astonishing density and remarkable longevity. Compared to conventional magnetic or solid-state drives, DNA can theoretically store 215 petabytes of data in a single gram-equivalent to approximately 340 billion high-definition movies. More crucially, DNA exhibits exceptional archival stability; properly preserved, genetic information can endure for hundreds of thousands, even millions, of years, vastly outperforming any existing digital storage technology. This inherent robustness arises from DNA’s biological role as the carrier of hereditary information, naturally selected for preservation and replication. Consequently, DNA data storage is not simply about increasing capacity, but offering a truly long-term solution for preserving vital records, scientific datasets, and cultural heritage against the inevitable decay of traditional storage methods.

The promise of DNA data storage is tempered by the unpredictable nature of biological systems; inherent stochasticity at the molecular level presents a considerable hurdle to data fidelity. Errors can arise during DNA synthesis, sequencing, and enzymatic reactions-processes crucial for both writing and reading digital information. These aren’t simple binary failures, but rather random mutations or misinterpretations that can corrupt stored data. Researchers are actively exploring error-correction codes, similar to those used in traditional digital storage, but adapted to account for the unique error profile of DNA. Furthermore, strategies like redundant storage-creating multiple copies of data fragments-and robust encoding schemes are being developed to mitigate the impact of these stochastic events and ensure the long-term reliability of this revolutionary storage medium. Overcoming these challenges is pivotal to transforming DNA from a theoretical possibility into a practical reality for archiving the ever-growing digital universe.

Encoding Information: Expanding Capacity with Composite Letters

Directly encoding binary data into nucleotide sequences limits storage density to two states per nucleotide position. Utilizing ‘composite letters’-specifically, defined mixtures of all four nucleotides (adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine)-allows for the representation of multiple data values within a single nucleotide position. This is achieved by assigning probabilities to each nucleotide within the composite letter, effectively creating a probability distribution that encodes information. For example, a composite letter might consist of 50% adenine, 25% guanine, 15% cytosine, and 10% thymine, representing a distinct data value separate from other possible composite letter combinations. This increases the information capacity beyond a simple binary scheme, allowing for greater data density within the DNA storage medium.

The encoding scheme utilizes a multinomial channel to represent data transmission, conceptualizing each composite letter as a probability distribution over the four possible nucleotides-adenine, guanine, cytosine, and thymine. Instead of a binary signal having a defined state, each composite letter is defined by the probability of observing each nucleotide when sequenced. These probabilities, represented as a four-dimensional vector where each element sums to one, constitute the channel characteristics for that specific letter. Variations in nucleotide frequencies due to sequencing errors or biological processes are therefore modeled as deviations from this defined probability distribution, allowing for robust data retrieval even with imperfect reads. The use of a multinomial distribution accounts for the possibility of observing any combination of nucleotides, weighted by their respective probabilities within the composite letter.

Encoding data with composite letters enables a visualization technique analogous to constellation diagrams used in digital communication systems. In these diagrams, each composite letter-representing a symbol-is plotted based on the probabilities of its constituent nucleotides being observed. This results in a cluster of points, where the position and spread of each cluster reflects the probability distribution of that specific composite letter. Analyzing the separation and distinctness of these clusters allows for the assessment of encoding robustness and potential for error correction, mirroring the signal space analysis performed in traditional modulation schemes such as quadrature amplitude modulation (QAM) or phase-shift keying (PSK). The constellation diagram therefore provides a geometric representation of the encoded data, facilitating the evaluation of encoding efficiency and error characteristics.

LDPC Codes: A Robust Framework for Error Correction

Low-Density Parity-Check (LDPC) codes are utilized to mitigate errors inherent in DNA sequencing processes. These codes function by adding redundant information to the original data, enabling the detection and correction of errors introduced during sequencing or data transmission. LDPC codes are characterized by their sparse parity-check matrices, which facilitate efficient decoding algorithms and allow for high performance even with relatively simple implementations. The efficacy of LDPC codes stems from their ability to approach the Shannon limit, representing a theoretical maximum for reliable communication over noisy channels, and their suitability for iterative decoding schemes that progressively refine the estimated sequence.

The implementation utilizes Low-Density Parity-Check (LDPC) codes with varying rates – 0.3235, 0.5, and 0.75 – to manage the balance between data redundancy and error correction strength. A rate of 0.3235 introduces the highest level of redundancy, providing the strongest error correction at the cost of reduced data throughput; for every 100 data bits, 323.5 parity bits are added. Conversely, a rate of 0.75 minimizes redundancy, with only 75 parity bits added per 100 data bits, resulting in higher throughput but reduced error correction capability. The 0.5 rate code represents an intermediate trade-off, offering a balance between these two extremes, and allowing for selection based on the specific requirements of the application and the expected error rate of the sequencing process.

The Log-SPA (Log-Sum-Product Algorithm) is employed for decoding LDPC codes due to its computational efficiency and performance. This iterative algorithm operates by propagating probabilistic messages – specifically, Log-Likelihood Ratios (LLR) – between variable nodes (representing bits in the original sequence) and check nodes (representing parity checks). LLR values quantify the confidence in each bit being a 0 or a 1, based on the received signal and prior knowledge. During each iteration, the Log-SPA algorithm updates these LLRs, refining the probability estimates until a valid codeword – the most likely transmitted sequence – is determined. The algorithm terminates when a stable solution is reached or a maximum number of iterations is exceeded, providing a corrected sequence with minimized errors.

Achieving Near-Zero Error Rates: Adapting to Sequencing Imperfections

DNA sequencing, while a cornerstone of modern biology, is not without its inherent limitations. The process is susceptible to a variety of errors that can compromise the accuracy of genomic data; these include substitutions – where one nucleotide is incorrectly read for another – as well as insertions and deletions, where nucleotides are either added or omitted during the reading process. Beyond these technical challenges, the very nature of sampling introduces a degree of randomness – a finite number of DNA fragments are analyzed, representing only a portion of the complete genome, and therefore, statistical fluctuations can occur. These combined error sources demand sophisticated strategies for error correction and data validation to ensure reliable genomic analysis and interpretation, particularly when dealing with complex biological systems or clinical diagnostics.

The inherent fallibility of DNA sequencing-prone to substitutions, insertions, and deletions-necessitates a proactive approach to error mitigation. This work introduces a ‘Constellation Update Policy,’ a dynamic decoding mechanism designed to adapt in real-time to observed error patterns. Rather than relying on static error correction, the policy continuously refines the decoding process based on the specific types and frequencies of errors encountered within a given sample. This adaptive strategy allows the system to prioritize correction efforts where they are most needed, effectively minimizing the impact of sequencing imperfections and significantly improving the overall reliability of the results. The policy’s effectiveness lies in its ability to move beyond generalized correction and towards a personalized approach to error handling, yielding substantial improvements in accuracy.

The research demonstrates a substantial reduction in sequencing inaccuracies through the synergistic application of error correction and adaptive decoding techniques. Results indicate the ability to achieve near-zero Block Error Rates (BLER) even with a limited number of DNA samples, as visually represented in Figure 2. Rigorous validation was performed by systematically evaluating performance across a spectrum of error probabilities, including substitution rates ranging from 0.01 to 0.4 – detailed in Figure 3 – and insertion/deletion probabilities of 0.001 and 0.002, as shown in Figure 4. This comprehensive assessment confirms the system’s resilience and reliability in handling inherent sequencing errors, paving the way for more accurate and dependable genomic analyses.

The pursuit of denser data storage, as explored in this work regarding composite DNA letters, necessitates a holistic understanding of system behavior. The study demonstrates that established error correction methodologies, like LDPC codes, can be adapted to address the challenges posed by realistic error profiles-substitutions, insertions, and deletions-within this novel storage medium. This approach echoes the sentiment of Henri Poincaré, who observed, “It is through science that we arrive at truth, but it is imagination that makes us seek it.” The research doesn’t merely apply existing codes; it reimagines their role within a fundamentally different data storage paradigm, prioritizing system-level robustness alongside density, acknowledging that a fix to one component requires comprehension of the whole.

Future Directions

The pursuit of denser data storage inevitably leads to systems where error profiles become more complex. This work demonstrates a degree of resilience in composite DNA storage using established error correction – a reassuring sign. However, the analogy to a city’s infrastructure holds: simply reinforcing existing structures only delays the need for fundamental redesign. The multinomial channel, while a useful abstraction, skirts the biophysical realities of DNA synthesis and sequencing; these processes introduce correlations between errors that current codes do not explicitly address.

Future investigations should focus less on simply correcting errors, and more on anticipating them. A truly elegant system would incorporate knowledge of the error-generating mechanisms directly into the encoding process – designing ‘letters’ not for optimal information content, but for minimal susceptibility to misinterpretation. Furthermore, the current framework treats error correction as a post-hoc step. A more holistic approach might consider integrated encoding-decoding schemes where error mitigation is inherent in the data representation itself.

Ultimately, the limitations are not in the codes, but in the medium. DNA is not silicon. The challenge lies not in squeezing more information into a given space, but in building a system that acknowledges-and even leverages-the inherent imperfections of the biological substrate. The goal is not flawless storage, but robust, adaptive resilience.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.11951.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- How to Build Muscle in Half Sword

- One Piece Chapter 1174 Preview: Luffy And Loki Vs Imu

- Epic Pokemon Creations in Spore That Will Blow Your Mind!

- Top 8 UFC 5 Perks Every Fighter Should Use

- All Pistols in Battlefield 6

- Gears of War: E-Day Returning Weapon Wish List

- Bitcoin Frenzy: The Presales That Will Make You Richer Than Your Ex’s New Partner! 💸

- How To Get Axe, Chop Grass & Dry Grass Chunk In Grounded 2

- Bitcoin’s Big Oopsie: Is It Time to Panic Sell? 🚨💸

- RPGs Where You Are A Nobody

2026-02-14 01:32