Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers are leveraging zero-knowledge technology to create cryptographic guarantees that confirm the exact origin and compilation process of software binaries.

This paper details a method for establishing software provenance using zero-knowledge virtual machines to generate proofs of compilation from source code.

Establishing trust in software supply chains remains a critical challenge, particularly verifying that a compiled binary genuinely originates from its claimed source code. This paper, ‘Verifiable Provenance of Software Artifacts with Zero-Knowledge Compilation’, introduces a novel solution leveraging zero-knowledge virtual machines (zkVMs) to generate cryptographic proofs of compilation. By executing a compiler within a zkVM, the system produces both the compiled output and a succinct proof attesting to its integrity and origin. This approach demonstrates strong security guarantees against various adversarial attacks and offers a path towards more robust and verifiable software provenance-could zk-compilation become a standard practice for securing the software ecosystem?

The Software Supply Chain: A Crisis of Unearned Trust

The contemporary landscape of software development relies on intricate supply chains, where code components, libraries, and tools frequently originate from diverse and often distributed sources. This complexity, while enabling rapid innovation and specialization, simultaneously presents a significantly expanded attack surface for malicious actors. Vulnerabilities can be introduced not only through compromised source code-such as backdoors or deliberately weakened cryptography-but also through the subversion of essential build tools, most notably compilers. An attacker successfully compromising a widely used compiler, for instance, could subtly alter the compilation process, injecting malicious code into any software built with that tool, effectively creating a systemic vulnerability impacting countless users and systems. The sheer scale and interconnectedness of these modern supply chains make identifying and mitigating such threats exceptionally challenging, demanding a fundamental shift in how software integrity is assured.

Contemporary software security frequently prioritizes identifying malicious activity during a program’s operation – a reactive approach that often proves insufficient. This emphasis on runtime detection overlooks a critical vulnerability: the software build process itself. Attacks like compiler substitution, where a legitimate compiler is replaced with a compromised version, can inject malicious code directly into a binary before it even runs, effectively bypassing many runtime defenses. Because these alterations occur upstream, during compilation, the resulting software appears normal during execution, making detection exceptionally difficult. This highlights a fundamental shift needed in security thinking – moving beyond simply monitoring what software does, to verifying how it was created, and ensuring the integrity of the entire build pipeline.

The pervasive reliance on software across critical infrastructure and daily life is increasingly challenged by a fundamental crisis of trust. Without verifiable assurance of a binary’s origin and integrity, users and organizations operate with an unacceptable level of risk. This isn’t merely a concern for cybersecurity professionals; compromised software can impact everything from financial transactions and healthcare systems to transportation networks and national security. The difficulty in definitively establishing a software’s provenance – knowing exactly who built it and that it hasn’t been tampered with – erodes confidence in the digital tools that underpin modern society. Consequently, a growing need exists for robust mechanisms to guarantee software authenticity, fostering a digital ecosystem where reliance isn’t predicated on blind faith, but on demonstrable proof of integrity.

Establishing definitive correspondence between source code and its compiled binary remains a significant challenge in software security. Current verification techniques, while helpful in identifying certain anomalies, often fall short of providing absolute proof of integrity; they may confirm a binary appears correct based on specific tests, but cannot guarantee it faithfully represents the developer’s original intent. This limitation stems from the inherent complexity of the compilation process itself, which involves numerous transformations and optimizations that obscure the direct relationship between the two forms. Consequently, malicious actors can subtly alter code during compilation – through techniques like compiler substitution or the injection of hidden functionality – without necessarily triggering existing detection mechanisms. This creates a critical vulnerability, as assurances based on runtime behavior alone are insufficient to guarantee that a seemingly functional binary hasn’t been tampered with at its foundational level, leaving users reliant on a system where trust is not definitively earned, but rather, cautiously assumed.

Verifiable Compilation: A Chain of Cryptographic Custody

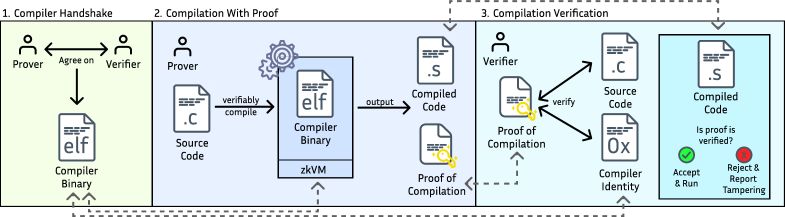

Verifiable compilation enhances software security by constructing cryptographic proofs during the compilation process itself. This proactive approach differs from traditional security measures which typically analyze binaries after compilation. The generated proof mathematically links the source code to the resulting binary, creating an auditable record of the build process. This linkage is established through a deterministic compilation process, meaning identical source code will always produce the same proof and binary. The resulting cryptographic proof then serves as a guarantee of the binary’s origin and integrity, independent of trust in the compiler or build environment.

Zero-Knowledge Virtual Machines (zkVMs) facilitate the creation of cryptographic proofs, specifically succinct non-interactive arguments of knowledge (SNARKs), that attest to the correct compilation of source code into a binary executable. The zkVM executes the compilation process within a controlled environment, generating a proof that the resulting binary is indeed derived from the designated source. Crucially, the proof itself does not expose the source code; it only confirms the validity of the compilation without revealing the underlying logic. This is achieved through zero-knowledge principles, where the verifier can confirm the statement (correct compilation) without learning anything about the witness (the source code). The resulting proof can then be independently verified to establish the integrity of the binary, guaranteeing its provenance and authenticity.

Cryptographic proof verification establishes binary integrity by mathematically confirming the correspondence between a compiled binary and its original source code. This process doesn’t require access to the source code itself; instead, a verifier can examine the generated proof – a concise cryptographic attestation – to determine if the binary has been modified since compilation. Successful verification assures that the binary’s instructions precisely reflect the developer’s intent, effectively mitigating risks associated with malicious alterations or unintended changes introduced during the build process. The verification process relies on the cryptographic properties of the proof, ensuring that any tampering would invalidate the proof and be readily detectable.

Compiler substitution attacks, where malicious code is introduced during the compilation process, and subsequent binary code tampering are directly mitigated by verifiable compilation techniques. Traditional software supply chains lack inherent safeguards against these threats, leaving systems vulnerable to compromised binaries. Verifiable compilation establishes a cryptographic link between source code and the resulting binary, allowing independent verification that the deployed code precisely reflects the intended, original source. This cryptographic assurance builds a strong foundation for software trust by enabling any party to validate the integrity of the binary without requiring access to the source code or trusting the compiler itself.

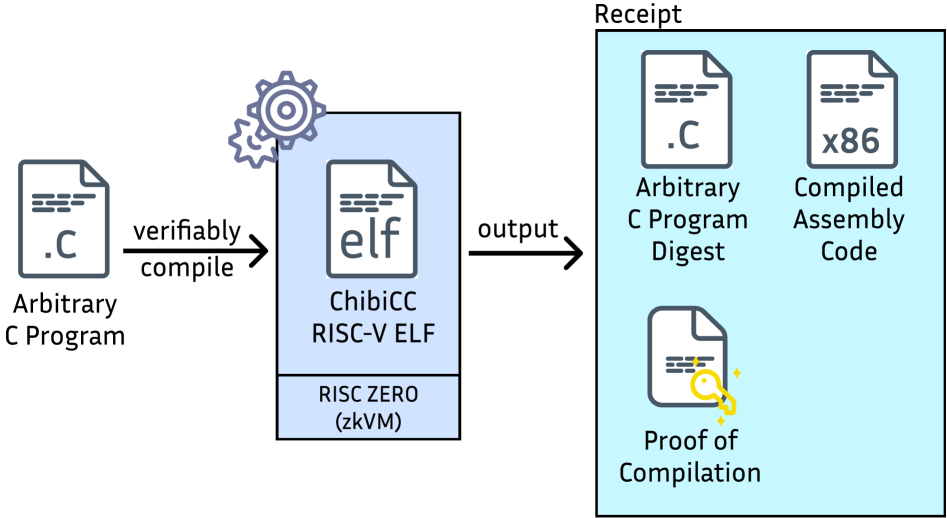

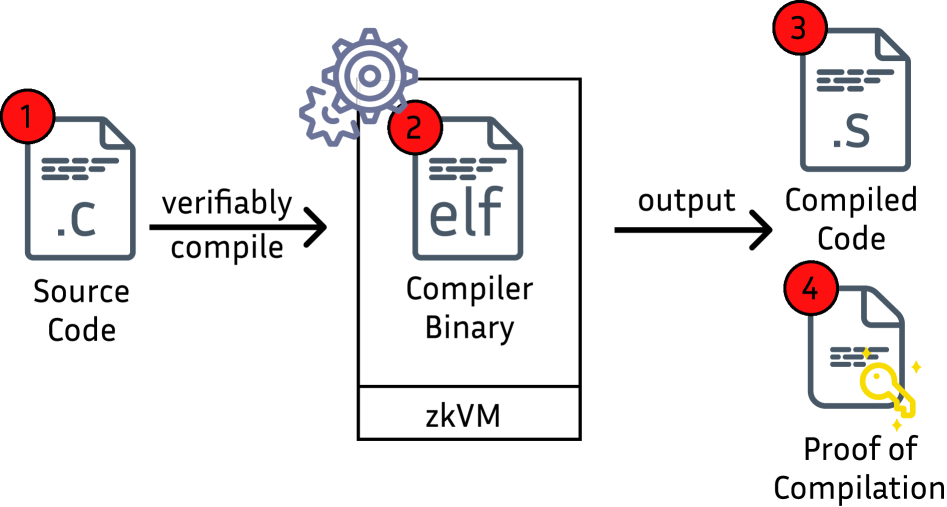

Prototyping and Testing: A Csmith Gauntlet

The prototype system employs the ChibiCC compiler as a front-end to translate C code into an intermediate representation. This representation is then processed by the RISC Zero zkVM, a zero-knowledge virtual machine, to generate a cryptographic proof of correct compilation. This proof assures that the code executed within the zkVM is equivalent to the original C source code. The system is designed to create a verifiable link between the high-level C code and the low-level execution, establishing trust in the compilation process itself. The resulting proof can be independently verified, confirming the integrity of the compiled program without requiring access to the original source code or the compiler.

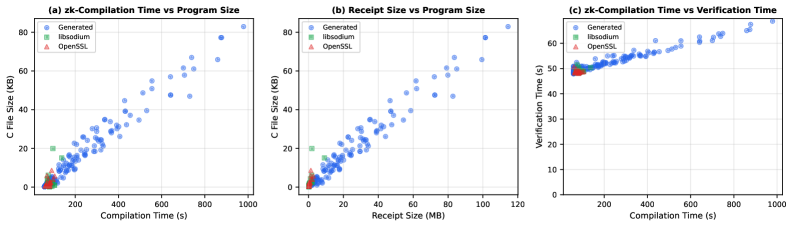

The evaluation of the verifiable compilation system incorporates Csmith, a tool designed to automatically generate a wide range of C programs. This approach enables systematic testing with diverse and often complex code structures, exceeding the coverage achievable through manually written test cases. By subjecting the proof generation process to randomly generated programs, the system’s robustness and ability to handle varied code patterns can be rigorously assessed. The use of Csmith facilitates identification of potential failure points or performance bottlenecks related to specific code constructs, providing a more comprehensive evaluation than limited, hand-crafted examples.

The RISC Zero ImageID functions as a cryptographic commitment to the compiler used in generating proofs. This ID, derived from the compiler’s code and configuration, provides a unique fingerprint enabling verification that a specific, known compiler version was utilized. Inclusion of the ImageID in the proof generation process establishes a crucial link in the chain of trust, allowing consumers of the proof to confidently ascertain the integrity of the compilation stage, independent of trust in the proof system itself. This ensures that any alterations to the compiler would result in a different ImageID, invalidating subsequent proofs and preventing malicious code injection through compiler manipulation.

Demonstrated feasibility of verifiable C compilation relies on benchmark performance data obtained from processing 200 randomly generated C programs using Csmith. Median compilation times, leveraging the ChibiCC compiler and RISC Zero zkVM, ranged from 57.01 to 979.12 seconds. Critically, the median time required for subsequent proof verification was substantially lower, falling between 47.93 and 68.75 seconds. This performance differential indicates a scalable approach where the computationally intensive compilation is performed once, and verification-essential for trust-can be achieved efficiently.

Receipt size, representing the data required to verify the compilation proof, is directly correlated with the complexity of the compiled C program. Testing revealed receipt sizes ranging from 0.27 MB for minimal programs to 120 MB for larger, more complex codebases. This variance is expected, as more intricate programs necessitate larger proofs to attest to their correct compilation. The receipt encapsulates the compiled code’s hash, the zkVM execution trace, and cryptographic commitments, all contributing to its overall size. Storage and transmission costs associated with these receipts must be considered when deploying this system at scale.

Beyond Verification: Building a Robust Provenance Ecosystem

A robust software provenance strategy extends significantly beyond simply verifying that source code compiles correctly. While crucial, verifiable compilation provides only a partial picture of a software artifact’s history. Complementary methods, such as reproducible builds – which ensure identical binaries are created from the same source given the same build environment – bolster confidence by mitigating the impact of compromised build systems. Similarly, binary-source matching techniques analyze compiled code to identify connections to original source code repositories, effectively reconstructing provenance even when direct build logs are unavailable or untrustworthy. These combined approaches create a more resilient and complete record of a software component’s origins and transformations, strengthening defenses against supply chain attacks that attempt to introduce malicious code or compromise legitimate software.

Binary-source matching offers a powerful approach to reconstructing software provenance, particularly when build records are incomplete or unavailable. Tools such as BinPro operate by comparing the machine code of a compiled binary against a vast database of source code repositories. This process identifies segments of code within the binary that closely resemble source code functions, effectively linking the binary back to its origins and revealing the codebase used in its creation. While not a perfect solution – code obfuscation and significant alterations can hinder accurate matching – this technique provides a crucial layer of defense by uncovering previously unknown dependencies and verifying the integrity of software components, even in the absence of complete build histories.

Proof-Carrying Code (PCC) and formal verification represent advanced strategies for bolstering software trustworthiness by shifting the burden of proof regarding code correctness. Rather than simply testing for errors, these techniques employ mathematical rigor to prove that a program adheres to a specified contract or policy. PCC, for instance, involves packaging code with a formal proof demonstrating its compliance with defined safety properties, allowing a verifier to confidently execute the code without needing to independently assess its security. Formal verification, meanwhile, utilizes logical systems to exhaustively check code against its intended behavior, identifying potential vulnerabilities that traditional testing might miss. The integration of such methods offers a significantly heightened level of assurance, particularly critical in high-security contexts where even subtle flaws could have severe consequences, and complements other provenance techniques by validating not just how software was built, but that it behaves as expected.

A robust defense against escalating software supply chain attacks necessitates a layered approach extending beyond simply verifying code compilation. By integrating techniques like reproducible builds – ensuring identical binaries are produced from the same source code – with binary-source matching and formal verification methods, a significantly more resilient system emerges. This combined strategy doesn’t rely on a single point of trust; instead, it creates multiple validation checkpoints, making it substantially harder for malicious actors to compromise software integrity. The ability to trace a binary back to its source, coupled with assurances of code correctness, offers a powerful shield against tampering and the introduction of vulnerabilities, thereby bolstering confidence in the software ecosystem and safeguarding users from increasingly complex threats.

The pursuit of verifiable provenance, as outlined in the paper, feels less like securing a system and more like building a slightly more elaborate sandcastle against the tide. One anticipates the inevitable erosion. As Linus Torvalds once said, “Talk is cheap. Show me the code.” This sentiment resonates deeply; cryptographic proofs are elegant in theory, but the real test lies in deployment. The paper’s focus on zero-knowledge compilation offers a potential path to establishing trust, yet one remembers that even the most robust system ultimately depends on the integrity of the underlying hardware and the fallibility of human operators. It’s a noble effort, but history suggests that perfect security is a mirage.

What’s Next?

The pursuit of verifiable software provenance, as outlined in this work, inevitably bumps against the realities of production systems. Cryptographic proofs are elegant, yes, but they add latency. Zero-knowledge virtual machines are fascinating, but they are, at their core, expensive ways to complicate everything. The immediate challenge isn’t proving a binary’s origin; it’s convincing operations teams to tolerate the performance overhead. The truly difficult problem lies not in generating proofs, but in managing and validating them at scale, across diverse and rapidly changing infrastructure.

One anticipates a proliferation of tooling focused on automating proof generation and verification. However, automation introduces its own set of concerns. If the tooling itself is not auditable, the provenance chain is merely extended, not secured. The emphasis will likely shift from theoretical guarantees to pragmatic trade-offs: acceptable levels of overhead, tolerable false positive rates, and the cost of remediation when, inevitably, something breaks. If code looks perfect, no one has deployed it yet.

The longer-term question is whether this approach fundamentally alters the software development lifecycle, or simply adds another layer of complexity. History suggests the latter. Each ‘revolutionary’ framework eventually becomes tomorrow’s tech debt. This work provides a valuable contribution to the field, but a cautious optimism is warranted. The real test will be whether these cryptographic assurances outweigh the practical difficulties of maintaining them in a world where ‘good enough’ often trumps ‘provably secure’.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.11887.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- How to Build Muscle in Half Sword

- Top 8 UFC 5 Perks Every Fighter Should Use

- One Piece Chapter 1174 Preview: Luffy And Loki Vs Imu

- Epic Pokemon Creations in Spore That Will Blow Your Mind!

- How to Play REANIMAL Co-Op With Friend’s Pass (Local & Online Crossplay)

- All Pistols in Battlefield 6

- Gears of War: E-Day Returning Weapon Wish List

- Bitcoin Frenzy: The Presales That Will Make You Richer Than Your Ex’s New Partner! 💸

- How To Get Axe, Chop Grass & Dry Grass Chunk In Grounded 2

- Bitcoin’s Big Oopsie: Is It Time to Panic Sell? 🚨💸

2026-02-14 08:22