Author: Denis Avetisyan

New measurements of elliptic flow in isobar collisions at RHIC reveal details about the collective behavior of matter and the role of nuclear shape.

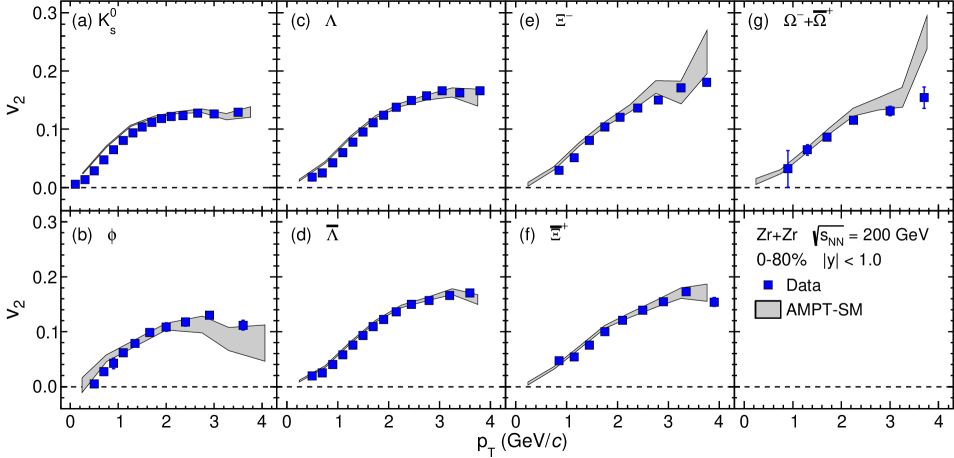

This study presents measurements of elliptic flow for strange and multi-strange hadrons produced in isobar collisions at $\sqrt{s_{\mathrm {NN}}} = 200\mathrm{~GeV}$ at RHIC, providing insights into both the Quark-Gluon Plasma and nuclear deformation effects.

Understanding the equation of state and collective behavior of nuclear matter at extreme conditions remains a central challenge in relativistic heavy-ion physics. This is addressed in ‘Elliptic flow of strange and multi-strange hadrons in isobar collisions at $\sqrt{s_{\mathrm {NN}}} = 200\mathrm{~GeV}$ at RHIC’, where measurements of elliptic flow-a hallmark of collective dynamics-are presented for a range of strange and multi-strange hadrons produced in collisions of isobars. The observed scaling of v_2 with the number of constituent quarks suggests the development of partonic collectivity, while subtle differences in v_2 between the isobar systems point to variations in nuclear deformation. Do these findings offer a refined understanding of the Quark-Gluon Plasma and the nuanced structure of nuclear matter under extreme conditions?

Deconstructing the Void: Unveiling the Quark-Gluon Plasma

The fundamental theory of the strong force, Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD), posits that under ordinary conditions, quarks and gluons – the building blocks of protons and neutrons – are confined within hadrons. However, QCD predicts a phase transition at extraordinarily high temperatures and densities, liberating these particles into a new state of matter known as the Quark-Gluon Plasma (QGP). This isn’t simply a gas of free quarks and gluons; instead, it’s a deconfined liquid where the strong force is effectively weakened, allowing quarks and gluons to move with reduced interaction. The existence of the QGP represents a crucial prediction of QCD, and its observation provides a unique window into the behavior of matter under conditions not seen since the very first moments after the Big Bang, offering insights into the fundamental nature of strong interactions and the origins of mass.

The creation of the Quark-Gluon Plasma, a state of matter predicted by Quantum Chromodynamics, demands an immense concentration of energy achieved through the collision of heavy ions – typically gold or lead – at velocities approaching the speed of light. Facilities like the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) at Brookhaven National Laboratory and the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN are uniquely equipped for this task. These colliders accelerate ions to relativistic speeds and then smash them together, briefly recreating the extreme conditions thought to have existed microseconds after the Big Bang. The resulting interactions produce a fleeting, incredibly hot and dense environment where protons and neutrons ‘melt’ into their constituent quarks and gluons, forming the QGP. Studying the debris from these collisions allows physicists to indirectly probe the properties of this exotic state of matter and test the predictions of QCD under conditions impossible to replicate naturally on Earth.

Determining the characteristics of the Quark-Gluon Plasma – specifically how quickly it reaches thermal equilibrium (thermalization), its relationship between pressure, temperature, and density (equation of state), and how efficiently it transports energy and momentum (transport coefficients) – represents a critical test of Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD). These properties aren’t merely descriptive; they reveal the fundamental dynamics of the strong force, the interaction binding quarks and gluons within hadrons. A thorough understanding of these parameters allows physicists to compare theoretical predictions from QCD with experimental observations, effectively validating the theory at extreme conditions. Deviations between prediction and experiment could indicate new physics beyond the Standard Model, hinting at modifications to our understanding of strong interactions and the very fabric of matter. Ultimately, precise measurements of the QGP’s characteristics provide insights into the behavior of matter at its most primordial state, moments after the Big Bang.

Flowing from Chaos: Mapping the Collective Behavior

Collective flow in heavy-ion collisions describes the correlated motion of produced particles, originating from the highly anisotropic, pressure-driven expansion of the quark-gluon plasma (QGP). This anisotropy is established in the initial stages of the collision, where the overlapping nuclei do not fully overlap, resulting in an almond-shaped region of high energy density. The pressure gradient arising from this spatial asymmetry drives a collective outward flow, which is then reflected in the azimuthal distribution of emitted particles. Measurements of this flow, quantified by flow coefficients, provide insights into the QGP’s equation of state and its thermalization process, effectively mapping the properties of this extreme state of matter.

Elliptic flow, denoted as v_2, provides insight into the early-stage dynamics and properties of the quark-gluon plasma (QGP). This anisotropic flow arises from the initial pressure gradients established in the spatially asymmetric overlap region of heavy-ion collisions. The magnitude of v_2 is highly dependent on the equation of state (EoS) of the QGP, specifically its pressure-to-energy density ratio. A softer EoS, indicating a less stiff plasma, results in a larger v_2, while a stiffer EoS leads to a smaller value. Furthermore, the observed magnitude of v_2 confirms that the QGP reaches a state of approximate thermal equilibrium, or thermalization, during its evolution, as a fully thermalized fluid exhibits the strongest collective flow.

Measurements of elliptic flow, denoted as v_2, across a range of hadron species – including the Ks0 meson, Lambda baryon, Phi meson, Xi baryon, and Omega baryon – provide insights into the properties of the quark-gluon plasma (QGP). Differential measurements of v_2 for strange and multi-strange hadrons, particularly in isobar collisions, support the mechanism of quark coalescence, where quarks produced in the QGP combine to form these hadrons. This observation validates the presence of strong partonic collectivity, indicating that quarks and gluons interact collectively within the QGP before hadronization, influencing the observed momentum correlations and allowing for detailed mapping of the QGP’s characteristics.

Deconstructing the Signal: Isolating the Primordial Fireball

The STAR detector, located at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC), is engineered to comprehensively analyze the particles created during heavy-ion collisions. Its core components include the Time Projection Chamber (TPC), which measures the trajectories and momenta of charged particles; the Vertex Position Detector (VPD), used to determine the collision’s primary vertex and event centrality; and the Time-Of-Flight (TOF) detector, which identifies particles based on their velocity. These detectors, working in concert, provide the precision needed to reconstruct collision events and measure the properties of the strongly coupled quark-gluon plasma (QGP) expected to be formed under extreme conditions. The detector’s acceptance covers pseudorapidities from -1.0 to +1.0 and full azimuthal coverage, allowing for comprehensive data collection.

Isobar collisions, specifically those utilizing nuclei like Ruthenium-96 (Ru-96) and Zirconium-96 (Zr-96), are employed to isolate the Quark-Gluon Plasma (QGP) signal from contributions arising from initial-state effects in heavy-ion collisions. These nuclei possess the same mass number (A=96) but differ in their neutron and proton composition, resulting in differing nuclear structures. By comparing collision data from different isobar pairs, physicists can systematically subtract or cancel out initial-state effects-such as variations in nuclear energy density and saturation-that are otherwise difficult to model accurately. This allows for a more precise determination of the properties of the QGP created in the collision, as the observed phenomena are less susceptible to ambiguities originating from the pre-collision state of the nuclei.

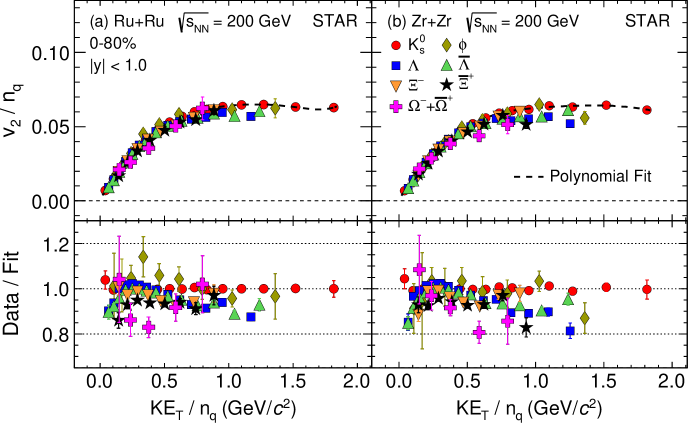

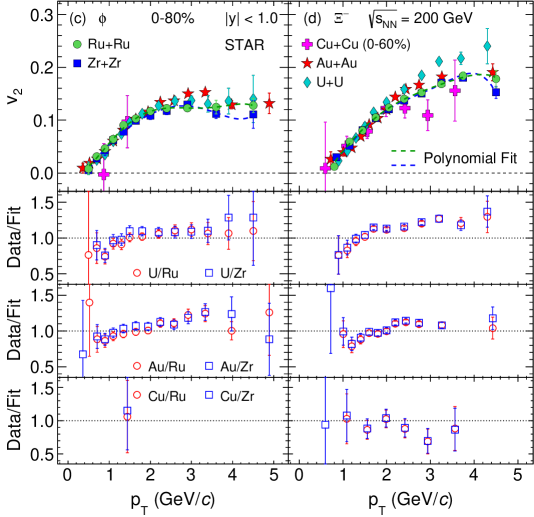

Accurate modeling of nuclear density distributions is crucial for interpreting results from isobar collisions at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC). The Woods-Saxon parameterization is a common technique employed to define these distributions, allowing for the calculation of collision geometries and subsequent hydrodynamic evolution. Analysis of the elliptic flow coefficient, v_2, in Ru-96+Ru-96 and Zr-96+Zr-96 collisions reveals a scaling relationship with the number of constituent quarks (n_q). This observed scaling is consistent with results obtained from gold-gold (Au+Au) and uranium-uranium (U+U) collisions, exhibiting agreement within a 20% uncertainty. This consistency strengthens the interpretation that the observed collective behavior in isobar collisions originates from the quark-gluon plasma (QGP) rather than purely from initial-state fluctuations or trivial correlations.

Refining the Lens: Unveiling Subtle Signatures

Researchers employ a technique called Number of Constituent Quarks (NCQ) scaling to refine the analysis of elliptic flow, a key observable in heavy-ion collisions. Elliptic flow, which reflects the collective behavior of the quark-gluon plasma (QGP), traditionally varies with particle type. By normalizing measurements of elliptic flow – represented as v_2 – by the number of constituent quarks in each particle species, scientists achieve a more standardized comparison. This scaling effectively isolates the influence of the QGP on particle production, rather than being masked by differences in particle size or composition. The result is a clearer understanding of how the QGP interacts with various degrees of freedom, ultimately allowing for more precise tests of theoretical models and a deeper probe into the fundamental properties of this exotic state of matter.

The AMPT model represents a sophisticated computational approach to understanding the extreme conditions created in heavy-ion collisions. This model simulates the entire collision process, from the initial energetic impact to the subsequent evolution of the quark-gluon plasma (QGP) and the eventual production of hadrons. By meticulously modeling these stages-including initial particle production, parton interactions, and hadronization-AMPT generates predictions for various observables, such as elliptic flow-a measure of the collective behavior of particles. These predictions are crucial because they offer a benchmark against which experimental data can be assessed. Direct comparison between modeled results and observations from experiments like those at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) and the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) allows physicists to validate or refine their understanding of the QGP’s properties, such as its viscosity and equation of state, and ultimately, to gain deeper insights into the fundamental nature of strong interactions.

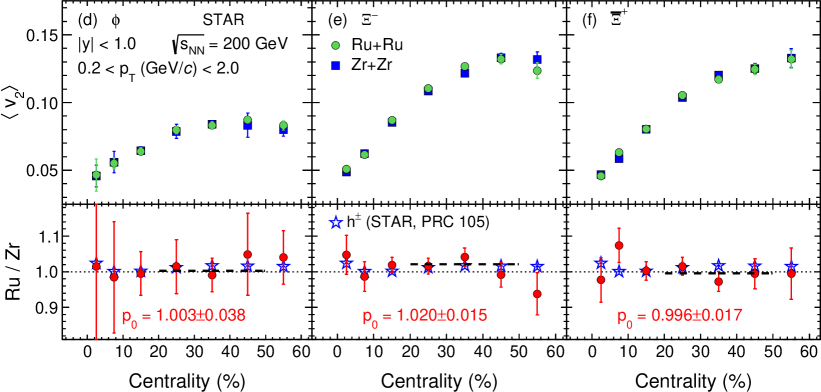

Recent investigations into heavy-ion collisions involving ruthenium (Ru) and zirconium (Zr) isotopes are revealing subtle, yet significant, details about the quark-gluon plasma (QGP). By comparing the elliptic flow, denoted as ⟨v2⟩, between Ru+Ru and Zr+Zr collisions-which differ only in their neutron excess-researchers are probing the Chiral Magnetic Effect (CME), a predicted phenomenon linking magnetic fields and the separation of chiral charges within the QGP. A deviation of approximately 2% in the ⟨v2⟩ ratio between these isobar systems has been observed in central and mid-central collisions, reaching a statistical significance of 3.7σ for K<sub>s</sub><sup>0</sup> mesons and an even more compelling 9.3σ for Lambda baryons. This observation provides further constraints on the properties of the QGP, suggesting the CME is indeed occurring and allowing scientists to refine their understanding of its fundamental structure and the behavior of chiral symmetry at extreme temperatures and densities.

The study meticulously dissects the collective behavior of strange and multi-strange hadrons, revealing subtle nuances within the Quark-Gluon Plasma formed during relativistic heavy-ion collisions. This pursuit of understanding echoes a sentiment articulated by Isaac Newton: “If I have seen further it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” Each measurement, each analysis of elliptic flow, builds upon prior knowledge, refining the picture of matter under extreme conditions. The researchers don’t simply accept existing models; instead, they probe the boundaries of hydrodynamic modeling, testing the limits of current understanding and, in doing so, expanding the foundations for future exploration. The investigation into nuclear deformation via the Woods-Saxon parameterization further exemplifies this drive to deconstruct and rebuild knowledge.

Uncharted Territory

The measured elliptic flow of strange and multi-strange hadrons, while illuminating, functions as a pointed reminder that the Quark-Gluon Plasma remains stubbornly opaque. Each refinement of hydrodynamic modeling, each attempt to disentangle initial-state effects from collective behavior, merely exposes the limitations of current tools. The Woods-Saxon parameterization, useful as it is, represents a simplification-a convenient fiction-and begs the question of how much of the observed flow is genuinely plasma-driven versus an artifact of the colliding nuclei’s imperfectly understood anatomy. To treat these nuclei as static, well-defined objects feels increasingly…naive.

Future investigations shouldn’t focus solely on achieving greater precision with existing parameters. Instead, the field should embrace avenues of inquiry that deliberately stress-test current assumptions. What happens when collisions are significantly more central, pushing the limits of hydrodynamic descriptions? Can measurements of higher-order flow coefficients reveal subtle deviations from predicted behavior, hinting at non-equilibrium dynamics or novel transport mechanisms? The true insights will likely emerge not from confirming expectations, but from the anomalies-the data points that refuse to fit the mold.

Ultimately, the pursuit isn’t about building a perfect model of the plasma-an exercise in recursive approximation. It’s about reverse-engineering the fundamental laws governing matter at extreme densities, a task that demands a willingness to dismantle established frameworks and explore the uncomfortable spaces between known physics.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.12094.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- One Piece Chapter 1174 Preview: Luffy And Loki Vs Imu

- Top 8 UFC 5 Perks Every Fighter Should Use

- How to Build Muscle in Half Sword

- How to Play REANIMAL Co-Op With Friend’s Pass (Local & Online Crossplay)

- Violence District Killer and Survivor Tier List

- Mewgenics Tink Guide (All Upgrades and Rewards)

- Epic Pokemon Creations in Spore That Will Blow Your Mind!

- Bitcoin’s Big Oopsie: Is It Time to Panic Sell? 🚨💸

- All Pistols in Battlefield 6

- Unlocking the Secrets: What Fans Want in a Minecraft Movie Sequel!

2026-02-15 04:47