Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have developed a novel time integration method that reliably maintains positivity and key invariants in simulations of dynamic systems.

This paper introduces a Patankar predictor-corrector scheme for positivity-preserving time integration of stiff ordinary differential equations, particularly those modeling production-destruction systems.

Maintaining positivity and conservation is a persistent challenge in the numerical solution of many dynamical systems. This is addressed in ‘A Patankar predictor-corrector approach for positivity-preserving time integration’, which introduces a modular correction strategy applicable to implicit Runge-Kutta schemes-specifically SDIRK methods-to enforce these crucial properties. The proposed method combines stage-wise clipping with ratio-based scaling, guaranteeing nonnegative, conservative solutions without substantial loss of accuracy for stiff production-destruction systems. Will this framework facilitate the development of robust and reliable integrators for increasingly complex models in fields like chemistry and fluid dynamics?

Navigating Stiff Systems: The Challenge of Timescale Disparity

The behavior of countless natural and engineered systems – from chemical kinetics and circuit analysis to weather patterns and biological processes – is frequently described using

The phenomenon of stiffness in dynamic systems emerges when processes occurring at drastically different rates – from incredibly fast to exceedingly slow – are modeled simultaneously. This disparity creates numerical instability for standard integration techniques; methods designed for systems evolving at comparable speeds become prone to oscillations or require impractically small time steps to maintain accuracy. Consider, for example, a chemical reaction involving both rapid diffusion and slow radioactive decay; accurately simulating this requires capturing both timescales, which conventional methods struggle with. Consequently, specialized numerical techniques, often involving implicit methods, are essential to resolve these systems efficiently and reliably, allowing researchers to model complex phenomena without succumbing to computational bottlenecks or inaccurate results. These advanced methods effectively dampen rapid changes while still accurately tracking the slower, long-term behavior of the system.

Numerical solutions of ordinary differential equations rely on stepping forward in time, and explicit methods achieve this by directly calculating the next state based on the current one. However, when systems exhibit vastly different timescales – a hallmark of ‘stiffness’ – these explicit methods become prone to instability unless impractically small time steps are used. This arises because information about the rapidly changing components struggles to propagate efficiently to the slower ones. Consequently, researchers often turn to implicit methods, which cleverly incorporate information about the future state into the current calculation, ensuring stability even with larger time steps. While this stability is a significant advantage, it comes at a cost: implicit methods require solving a system of equations at each time step, often involving computationally expensive matrix inversions or iterative solvers, making the overall simulation considerably slower than with simpler, explicit approaches.

L-Stability: A Foundation for Robust Simulation

L-stability, a key characteristic of implicit Runge-Kutta methods, addresses the challenges posed by stiff ordinary differential equations (ODEs). Stiffness arises when ODE systems have widely varying timescales, requiring very small step sizes for explicit methods to maintain stability. L-stable methods, however, possess the property that the stability region includes the entire left half-plane of the complex s-plane; mathematically, this means that for any

SDIRK21, SDIRK32, and SDIRK43 are examples of singly diagonally implicit Runge-Kutta (SDIRK) methods specifically designed for solving stiff ordinary differential equations (ODEs). These schemes achieve stability through L-stability, a property ensuring the method remains stable even as the step size approaches zero, a common issue with explicit methods applied to stiff problems. The specific configurations of these SDIRK methods – indicated by the numbers representing stages and order – balance computational cost with the desired level of accuracy. For example, SDIRK21 is a second-order method requiring two stages, while SDIRK43 is a fourth-order method using three stages, providing higher accuracy at the expense of increased computation per step. The L-stability of these methods guarantees bounded solutions even for highly stiff systems where explicit methods would require impractically small time steps to maintain stability.

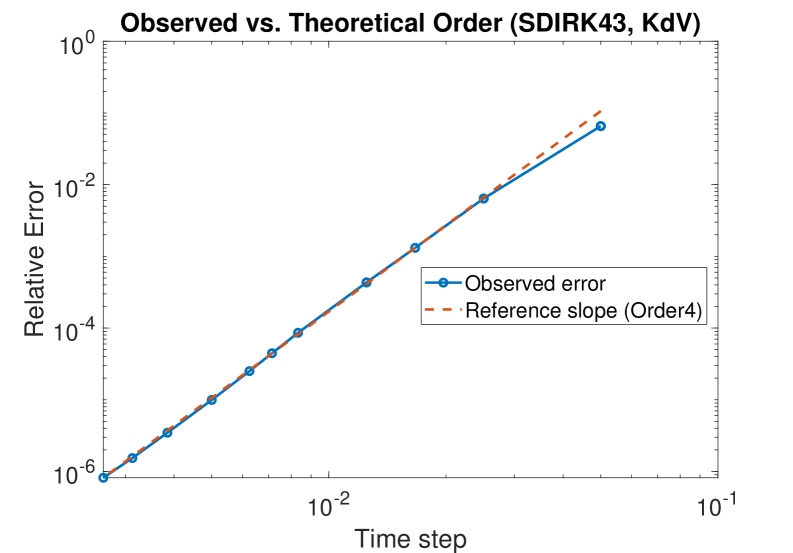

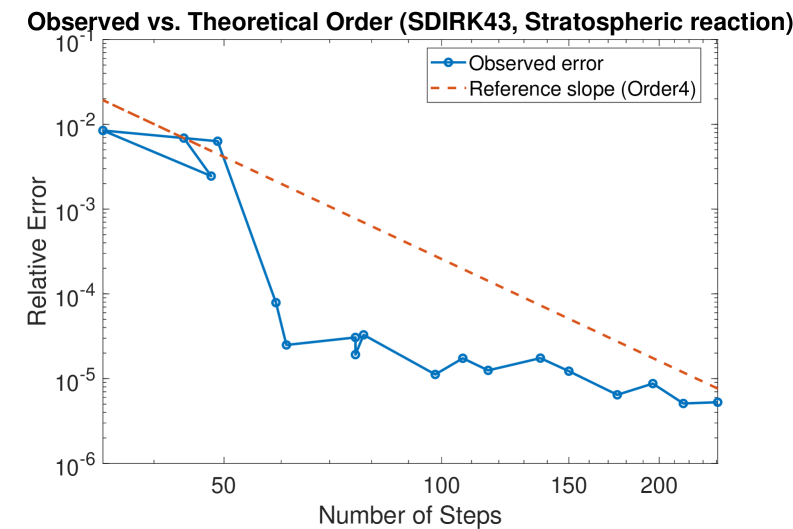

Several implicit Runge-Kutta schemes, including SDIRK21, SDIRK32, and SDIRK43, are designed to balance computational efficiency with solution accuracy. The number of stages in these schemes directly correlates with their computational cost; increasing the number of stages generally improves accuracy but requires more calculations per time step. The SDIRK43 scheme, specifically, achieves fourth-order accuracy while utilizing a relatively moderate number of stages. This means it maintains the expected global truncation error of

Enforcing Physical Realism: Positivity and Conservation as Guiding Principles

Numerous modeled systems, particularly in fields like chemical kinetics and population dynamics, are fundamentally constrained by the requirement of non-negative solutions; quantities such as species concentrations or population sizes cannot physically be less than zero. Standard numerical methods for solving the differential equations governing these systems, however, do not inherently enforce this constraint and can, through accumulated numerical error, produce negative values. This is not merely a mathematical inaccuracy but a failure to represent the physical reality of the modeled system. Consequently, post-processing techniques or specialized numerical schemes are often necessary to ensure that all solutions remain within the physically valid, non-negative domain.

The Patankar Predictor-Corrector method addresses numerical simulation challenges where maintaining non-negative values and conserved quantities is critical. This method operates as a post-processing step applied to the solution obtained from a primary numerical scheme. It iteratively adjusts the solution to enforce positivity constraints on variables like concentrations or populations, preventing physically unrealistic negative values. Crucially, the Patankar scheme is designed to achieve conservation of quantities such as total mass to machine precision; that is, any initial total mass is preserved throughout the simulation within the limits of computer floating-point representation. This is accomplished through a localized flux correction that redistributes mass while preserving the overall total, ensuring numerical accuracy and physical validity.

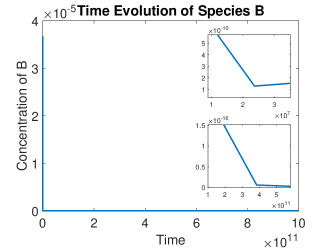

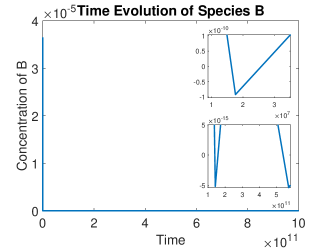

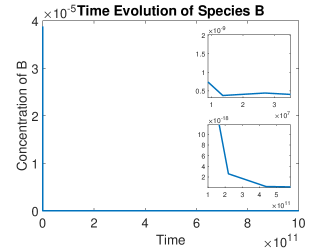

The integration of L-stable Runge-Kutta methods – specifically SDIRK21, SDIRK32, and SDIRK43 – with the Patankar Predictor-Corrector scheme yields a simulation approach that simultaneously ensures numerical stability and maintains physical realism in modeled systems. This combined methodology has been validated through application to a diverse set of benchmark problems, including the Robertson reaction, the MAPK cascade, a stratospheric chemical reaction model, and the Korteweg-de Vries (KdV) equation. These tests demonstrate the method’s ability to produce stable solutions while enforcing critical physical constraints, such as non-negativity of concentrations and conservation of mass, across varied dynamical systems.

Broadening the Scope: Applications and Impact Across Scientific Domains

The developed methodologies demonstrate broad applicability across diverse scientific disciplines reliant on ordinary differential equations (ODEs). Chemical reaction networks, such as those modeling production and destruction of key species, benefit from accurate timescale separation, allowing for efficient simulation of complex processes. Similarly, atmospheric chemistry, exemplified by the Stratospheric Reaction System, utilizes these techniques to predict the evolution of gas-phase reactions crucial for ozone depletion and climate modeling. Beyond chemistry, ecological models-which describe population dynamics and species interactions-also leverage these methods to understand ecosystem behavior and predict responses to environmental changes. This versatility highlights the potential of these tools to advance understanding and predictive capabilities in a wide range of interconnected fields.

Accurate predictive modeling hinges on the capacity to represent systems evolving across vastly different timescales, a challenge often overlooked in simplified representations. Many real-world phenomena – from biochemical reactions within a cell to climate patterns unfolding over decades – involve processes occurring at both rapid and glacial paces. Maintaining physical realism within these models isn’t merely about achieving quantitative accuracy; it’s about capturing the essential dynamics that govern system behavior. Without this fidelity, predictions can become skewed or even meaningless, hindering scientific discovery. For instance, failing to account for fast reaction rates in a chemical network could mask crucial intermediate steps, while ignoring slow ecological shifts could lead to inaccurate long-term forecasts. The ability to integrate these disparate timescales-to simulate both the immediate and the eventual-is therefore paramount for building robust and reliable models capable of advancing understanding across diverse scientific disciplines.

The methodology extends beyond systems governed by ordinary differential equations to encompass those described by partial differential equations, notably the Korteweg-de Vries (KdV) equation, thereby unlocking simulations of increasingly complex phenomena. While computational demands vary depending on the system modeled, the approach demonstrates a promising trade-off between accuracy and efficiency; simulations of the Robertson reaction exhibited a notable speedup. However, application to the stratospheric reaction system revealed a substantial increase in runtime, highlighting the need for continued optimization and adaptive algorithms to manage computational load when modeling systems with particularly intricate dynamics and multiple spatial dimensions. This adaptability suggests a broad applicability across diverse scientific fields, from fluid dynamics to atmospheric chemistry, paving the way for more realistic and predictive modeling capabilities.

The pursuit of robust numerical methods, as demonstrated in this work, aligns with a systemic understanding of problem-solving. A method’s ability to preserve positivity and invariants isn’t merely a technical detail, but a reflection of its internal coherence. As Sergey Sobolev noted, “The more complex the system, the more important it is to understand its fundamental principles.” This principle directly informs the development of the Patankar predictor-corrector method, which prioritizes maintaining key system properties-like non-negativity in production-destruction systems-through a carefully structured approach. The method’s success stems from recognizing that stability isn’t achieved through added complexity, but through a clear, well-defined structure that respects the underlying dynamics.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The pursuit of numerical methods often feels like chasing a receding horizon. This work, while demonstrably effective at preserving positivity and invariants – qualities frequently overlooked yet fundamentally important in modeling real-world systems – merely clarifies the shape of that horizon. The inherent challenge lies not in achieving local preservation, but in maintaining it globally, across extended time scales and complex system interactions. A method that functions flawlessly on isolated test problems may reveal subtle, yet critical, failings when confronted with the tangled dependencies of a truly representative model.

Future investigations should, therefore, move beyond isolated demonstrations. The focus must shift to assessing the long-term stability and robustness of these methods when applied to high-dimensional, multi-scale systems. Simplicity, after all, is not merely an aesthetic preference, but a necessary condition for understanding. If a design feels clever, it’s probably fragile. A truly elegant solution will be one that gracefully accommodates the inevitable imperfections of the underlying model, rather than attempting to force conformity upon a chaotic reality.

The preservation of invariants, while intuitively appealing, also raises a philosophical point. Are these invariants truly fundamental properties of the system, or simply artifacts of the model itself? Determining the difference will require a closer integration of numerical analysis with the underlying physical or biological principles. The goal isn’t simply to build better algorithms, but to build algorithms that reveal a deeper understanding of the systems they represent.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.15271.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Jujutsu Kaisen Modulo Chapter 23 Preview: Yuji And Maru End Cursed Spirits

- Mewgenics Tink Guide (All Upgrades and Rewards)

- 8 One Piece Characters Who Deserved Better Endings

- God Of War: Sons Of Sparta – Interactive Map

- Top 8 UFC 5 Perks Every Fighter Should Use

- How to Play REANIMAL Co-Op With Friend’s Pass (Local & Online Crossplay)

- How to Discover the Identity of the Royal Robber in The Sims 4

- Sega Declares $200 Million Write-Off

- Full Mewgenics Soundtrack (Complete Songs List)

- Who Is the Information Broker in The Sims 4?

2026-02-19 04:41