Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new analysis explores the subtle pathways of B meson decay involving D mesons and kaons, offering predictions for experimental verification.

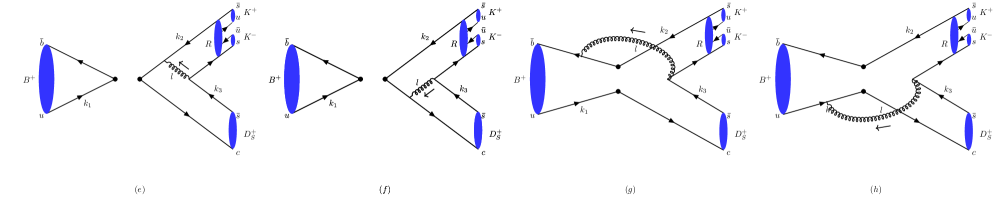

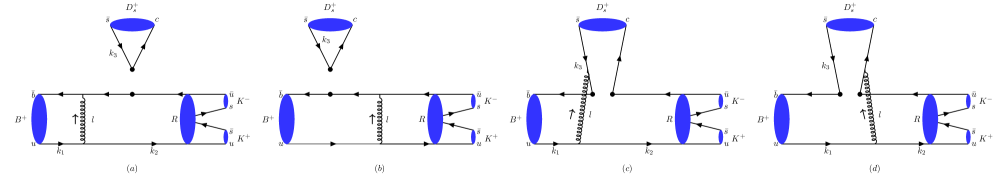

This study presents a perturbative QCD calculation of quasi-two-body $B^+ o D_s^+ (R o) K^+K^-$ decays, focusing on branching fractions and resonance structures.

Despite ongoing efforts to map the complexities of hadronic decays, a complete perturbative understanding of resonant contributions to quasi-two-body B^+\to D_s^+ K^+K^- decays remains elusive. This work, titled ‘Quasi-two-body decays $B^+\to D_s^+ (R\to) K^+K^-$ in the perturbative QCD approach’, presents a detailed analysis within the perturbative QCD (PQCD) framework, incorporating key S-, P-, and D-wave resonances. Our calculations yield the first PQCD predictions for branching fractions, demonstrating consistency with existing experimental data and providing a foundation for identifying resonance structures. Could deviations from these predictions-particularly nonzero direct CP asymmetries-signal physics beyond the Standard Model, prompting a deeper exploration of flavor dynamics?

The Illusion of Control: Resonances and the Limits of Prediction

The decay of B mesons into Ds mesons isn’t a straightforward process; it frequently involves the fleeting existence of intermediate resonant states. These resonances, created during the decay, act as temporary particles before ultimately transforming into the observed Ds mesons. Precisely modeling these intermediate steps is paramount because their characteristics-mass, width, and decay modes-directly influence the overall decay rate and the angular distribution of the final products. Failing to account for these resonances accurately leads to significant discrepancies between theoretical predictions and experimental measurements, obscuring the underlying physics of heavy quark decays and hindering efforts to probe the Standard Model with precision. Consequently, researchers dedicate substantial effort to refining techniques for identifying and characterizing these resonant contributions to ensure reliable theoretical calculations.

Predicting the rates at which B mesons decay into Ds mesons presents a significant challenge for conventional theoretical approaches, largely due to the intricate behavior of intermediate resonant states. These resonances-temporary, unstable particles appearing during the decay-do not behave as simple, well-defined entities; their broad widths and overlapping contributions introduce substantial uncertainties in calculations of decay amplitudes. Existing methods often rely on approximations that struggle to accurately capture the full complexity of these interactions, leading to discrepancies between predicted and observed decay rates. Specifically, modeling the interference patterns created by multiple overlapping resonances proves particularly difficult, requiring sophisticated techniques to disentangle their individual contributions and accurately determine the overall decay probability. Consequently, refining these modeling techniques remains crucial for achieving precise theoretical predictions and validating the Standard Model of particle physics.

The decay of B mesons into Ds mesons is heavily modulated by the presence of intermediate resonant states, notably the f0(980) and ϕ(1020). These resonances aren’t merely fleeting intermediaries; they act as amplifiers and suppressors of specific decay pathways, dramatically altering the observed decay rates. Their complex internal structure and relatively broad widths necessitate advanced theoretical techniques to accurately capture their contribution. Failing to properly account for these resonances introduces significant uncertainties into predictions of decay amplitudes and branching fractions, hindering precise comparisons with experimental results from facilities like the Large Hadron Collider. The subtle interplay between the decaying B meson and these resonances demands meticulous treatment, as even small inaccuracies in modeling can lead to discrepancies between theory and observation, obscuring the underlying physics.

The precision of theoretical predictions regarding B meson decay into Ds mesons hinges critically on the accurate representation of intermediate resonant states, a challenge made apparent by the wide range of predicted branching fractions – spanning from 10^{-8} to 10^{-6}. This sensitivity arises because these resonances, short-lived particles formed during the decay process, significantly contribute to the overall probability of the decay occurring. Discrepancies between theoretical calculations and experimental measurements are therefore often traced back to uncertainties in modeling these resonant contributions. Consequently, refining the treatment of these resonances isn’t merely a technical detail; it’s essential for validating the Standard Model and potentially uncovering new physics through precise comparisons with observed decay rates.

The Tools We Build: Perturbative QCD and Resonance Models

Perturbative Quantum Chromodynamics (PQCD) serves as the theoretical basis for calculating the probabilities of particle decays, quantified by decay amplitudes and branching fractions. PQCD utilizes the concept of perturbation theory, treating interactions between quarks and gluons as small deviations from free particle behavior, allowing for calculations based on Feynman diagrams and associated mathematical expansions. These calculations, performed to various orders of approximation, predict the rates for specific decay channels. Branching fractions, representing the proportion of decays leading to a particular final state, are directly determined from the calculated decay amplitudes. The accuracy of PQCD predictions depends on the order of the perturbative expansion and the energy scale of the process; at low energies, non-perturbative effects may become significant and require alternative approaches.

The Breit-Wigner formula is a standard analytical model used in particle physics to describe the resonant behavior observed in the decay of unstable, intermediate particles. It mathematically represents a resonance as a Lorentzian lineshape, characterized by a peak amplitude proportional to the decay rate and a width inversely proportional to the particle’s lifetime. Specifically, the formula expresses the scattering cross-section or decay rate as a function of energy, peaking at the resonance mass and broadening due to the uncertainty principle. Particles such as the f_0(1370) and \phi(1020) exhibit decay patterns well-approximated by the Breit-Wigner distribution, allowing for the determination of key properties like their mass and total width from experimental data. The formula is based on the assumption of a single-channel decay and a constant width, simplifying the analysis of resonant states.

The standard Breit-Wigner formula, while effective for describing the lineshape of many resonances, exhibits limitations when applied to broader or more complex decay scenarios. These inadequacies often arise from neglecting effects such as decay into channels not accounted for in the simplified two-body decay assumption, or from the resonance being close to the particle production threshold or another resonance. Specifically, the formula’s assumption of a single, isolated pole can fail when resonances overlap or when the decay width becomes comparable to the resonance mass, leading to distorted lineshapes and inaccurate predictions for decay rates. Consequently, more sophisticated models, incorporating features like coupled-channel dynamics and finite-width effects, are required to accurately represent the observed resonant behavior in these cases.

The Flatté model represents an improvement over the standard Breit-Wigner formula for describing resonances, particularly those exhibiting strong coupling to multiple decay channels or possessing a broad width. Unlike the Breit-Wigner, which assumes a single, isolated resonance, the Flatté model incorporates the effects of nearby resonances and the phase space available for various decay modes. This is achieved by parameterizing the amplitude with a pole term representing the resonance, alongside a background term accounting for non-resonant contributions and interference effects. The f0(980) meson serves as a key example, as its decay into two pions is significantly affected by the presence of the f0(1370) and the S-wave scattering amplitude, rendering a simple Breit-Wigner description inadequate. The Flatté model accurately captures these complexities by treating the resonance as part of a more complete scattering amplitude, allowing for a more precise determination of its mass, width, and coupling strengths.

Stripping Away the Ideal: Approximations in Two-Body Decay

The narrow-width approximation is a standard technique employed in calculations of two-body decays, particularly those involving intermediate resonant states. This approximation relies on the assumption that the width Γ of the resonant particle is significantly smaller than its mass m , such that \Gamma << m . Mathematically, this allows the decay amplitude to be factored into a product of a production amplitude, a propagator for the resonant state (approximated as a simple pole), and a decay amplitude. This simplification reduces the complexity of the integral over the phase space, transforming a complex multi-dimensional integral into a more readily solvable form. The validity of this approximation is contingent on the resonant state being sufficiently isolated, preventing significant contributions from nearby resonances or the continuum.

The narrow-width approximation, utilized in two-body decay calculations, is predicated on the assumption that the width Γ of any intermediate resonant state is significantly smaller than its mass m . This condition, \Gamma << m , allows the decay process to be treated as a two-step process: the initial particle first decays into the resonant intermediate, and then the intermediate decays into the final two-body state. Mathematically, this simplifies the decay amplitude by allowing the propagation of the intermediate particle to be described by a pole approximation, effectively removing the energy dependence of the propagator from the integral. This simplification greatly reduces the computational complexity of the calculation, enabling a more tractable analytical or numerical treatment of the decay process; however, the validity of the approximation relies on the narrowness of the resonance and can introduce inaccuracies if the width is not sufficiently small compared to the relevant energy scales.

Two-Kaon Distribution Amplitudes (TKDAs) parameterize the non-perturbative dynamics of the K^+K^-\ system, describing the probability amplitude for finding the two kaons with a specific momentum distribution and quantum numbers. These amplitudes function as essential input for calculating two-body decays involving the K^+K^-\ final state, as they represent the strong interaction effects governing the kaon pair’s internal structure. Accurate determination of TKDAs, typically through factorization or dispersion relation techniques, is therefore critical for reducing theoretical uncertainties in decay rate predictions; different models for the TKDAs can significantly impact calculated branching fractions and CP violation observables.

The precision of two-body decay calculations is fundamentally limited by the validity of employed approximations, notably the narrow-width approximation, and the accuracy of input parameters. Theoretical uncertainties are dominated by hadronic inputs, specifically the parameters defining the internal dynamics of the decaying particles – such as Two-Kaon Distribution Amplitudes. These hadronic parameters are often determined from experimental data or theoretical models, introducing inherent uncertainties that propagate through the decay calculations. While improvements in experimental precision and theoretical modeling can reduce these uncertainties, they remain the primary source of systematic error in determining decay rates and branching fractions.

The Ghost in the Machine: Implications Beyond the Standard Model

The rigorous testing of the Standard Model relies heavily on precise calculations of particle decays, and B meson decays are proving particularly insightful. These calculations aren’t simply about summing probabilities; they demand a detailed understanding of intermediate particles, known as resonances, that briefly form during the decay process. Resonances like f_2(1270) and f_2(1525) significantly influence the decay pathways and rates. Accurately incorporating their properties – mass, spin, and decay widths – into theoretical models is crucial for making reliable predictions. Discrepancies between these predictions and experimental observations, such as those gathered by the LHCb and Belle II collaborations, can then serve as compelling evidence for physics beyond the established Standard Model, potentially revealing new particles or interactions.

The pursuit of physics beyond the Standard Model often hinges on the subtle discrepancies between meticulously calculated theoretical predictions and the results obtained from high-energy particle experiments. While the Standard Model has proven remarkably successful, it fails to account for phenomena like dark matter and dark energy, suggesting the existence of undiscovered particles and interactions. Precise measurements of particle decays, such as those involving B mesons, serve as stringent tests of these theoretical frameworks; any deviation from predicted rates or angular distributions could signal the presence of new physics. These anomalies wouldn’t necessarily represent a complete overhaul of existing theory, but rather the first glimpses of previously unknown forces or particles influencing these decay processes, potentially opening pathways to a more complete understanding of the universe at its most fundamental level. The search for such inconsistencies remains a central focus in contemporary particle physics, driving the design and execution of experiments at facilities like the LHCb and Belle II.

A refined comprehension of particle decay mechanisms is paramount in the quest for physics beyond the Standard Model, specifically in identifying exceedingly rare or entirely forbidden decays. These decays, while improbable under established theory, could manifest if novel particles or interactions are present, offering a window into undiscovered phenomena. By meticulously mapping the established decay pathways and accurately predicting their rates, physicists can significantly enhance the sensitivity of experiments – like those at the LHCb and Belle II colliders – to deviations from expectation. Essentially, a detailed understanding of ‘normal’ decay behavior establishes a precise baseline against which to measure any anomalous signals, allowing researchers to confidently identify and investigate potential evidence of new physics lurking within the data.

Theoretical calculations predict a diverse range of decay probabilities for B mesons, quantified as branching fractions, which serve as crucial targets for experimental verification. Specifically, the decay of a B+ meson into a Ds meson, followed by further decay into pairs of K mesons through intermediate resonances, is expected to yield branching fractions spanning several orders of magnitude – from approximately 2.7 \times 10^{-8} for the f_0(980) resonance to 7.9 \times 10^{-7} for the f_2'(1525), with a value around 1.8 \times 10^{-7} expected for the \phi(1020) resonance. These precisely calculated values provide observable benchmarks for high-energy physics experiments such as LHCb and Belle II, allowing researchers to meticulously test the Standard Model and search for subtle deviations that could signal the presence of new particles or interactions.

The analysis meticulously predicts branching fractions for these quasi-two-body decays, a necessary, yet ultimately temporary, triumph of theory over the inevitable chaos of production environments. It’s a precise mapping of predicted behavior, destined to be subtly, then drastically, misaligned with observed data. As Niels Bohr observed, “Predictions are difficult, especially about the future.” This holds true even within the constrained world of flavor physics. The paper anticipates resonance structures, carefully calculating decay dynamics, but the universe rarely adheres to elegant calculations indefinitely. Each refinement of the perturbative QCD approach simply delays the moment it, too, becomes a footnote explaining why the latest measurements don’t quite fit.

What’s Next?

The pursuit of increasingly precise branching fraction predictions, even within a framework as theoretically dense as perturbative QCD, feels less like progress and more like accruing technical debt. This work, detailing quasi-two-body decays, provides numbers-elegant, complex numbers-but production will invariably uncover the unforeseen resonance, the subtle phase shift, the decay mode not fully accounted for in the hadronic wavefunctions. The model, like all models, is a simplification, and nature rarely cooperates with simplification.

Future iterations will undoubtedly focus on higher-order corrections, attempts to tame the infinities inherent in the perturbative expansion. This is a Sisyphean task, trading one set of approximations for another. A more fruitful, though perhaps less publishable, line of inquiry might involve confronting the limitations of the factorization assumptions. How robust are these predictions when confronted with genuinely strong-phase effects? The answer, it is suspected, will not be comforting.

Ultimately, the true test lies not in matching theoretical predictions to existing data-that is merely an exercise in parameter fitting-but in guiding experimental searches for genuinely new phenomena. The hope is that these calculations, despite their inherent imperfections, will at least point toward the correct places to look… before the next, more sophisticated, model renders them obsolete. Documentation, of course, remains a myth invented by managers.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.16423.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Poppy Playtime Chapter 5: Engineering Workshop Locker Keypad Code Guide

- Jujutsu Kaisen Modulo Chapter 23 Preview: Yuji And Maru End Cursed Spirits

- Mewgenics Tink Guide (All Upgrades and Rewards)

- 8 One Piece Characters Who Deserved Better Endings

- God Of War: Sons Of Sparta – Interactive Map

- Top 8 UFC 5 Perks Every Fighter Should Use

- How to Play REANIMAL Co-Op With Friend’s Pass (Local & Online Crossplay)

- How to Discover the Identity of the Royal Robber in The Sims 4

- Who Is the Information Broker in The Sims 4?

- How to Unlock & Visit Town Square in Cookie Run: Kingdom

2026-02-19 19:53