Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new method decouples learning representations from codebook optimization, addressing common instability issues in vector quantization techniques.

VP-VAE introduces adaptive vector perturbation to stabilize training and improve performance in discrete latent space models.

Despite the success of Vector Quantized Variational Autoencoders (VQ-VAEs) in generative modeling, their training is often hampered by instability and codebook collapse due to the tight coupling of representation learning and discrete codebook optimization. This paper introduces ‘VP-VAE: Rethinking Vector Quantization via Adaptive Vector Perturbation’, a novel framework that decouples these processes by reformulating quantization as a latent space perturbation achieved via distribution-consistent Metropolis–Hastings sampling. This approach eliminates the need for an explicit codebook during training, yielding more stable learning and improved reconstruction fidelity, while also providing a theoretical basis for lightweight fixed quantization schemes. Could this paradigm shift unlock more robust and efficient discrete representation learning beyond current VQ-VAE limitations?

Deconstructing Reality: The Rise of Discrete Representation

The current trajectory of machine learning is profoundly shaped by generative models, systems designed not just to recognize patterns but to understand and recreate the underlying structure of data. These models, ranging from Variational Autoencoders to Generative Adversarial Networks, achieve success by learning the complex probability distributions that govern real-world phenomena – essentially, figuring out how likely any given piece of data is to occur. This ability to model distributions is crucial for tasks like image generation, text synthesis, and even predicting future events. Unlike traditional discriminative models that simply classify data, generative models aim to capture the essence of the data, allowing them to produce new samples that convincingly resemble the original data source. The increasing sophistication of these models reflects a shift from simply recognizing what exists to understanding how things are created, opening new avenues for innovation across diverse fields.

Vector quantization offers a compelling strategy for distilling complex data into manageable, discrete representations. Rather than employing continuous latent spaces – which can be computationally expensive and difficult to interpret – this technique maps input data to a finite set of learned vector ‘codes’. This process effectively creates a ‘lookup table’ where similar inputs are assigned the same code, dramatically reducing the dimensionality of the data while preserving essential information. The resulting discrete latent space facilitates efficient representation, enabling models to generalize better from limited data and perform tasks like image generation or sequence modeling with fewer computational resources. By forcing the model to choose from a predefined set of options, vector quantization encourages the learning of meaningful, semantically relevant features, paving the way for more robust and interpretable machine learning systems.

The Vector Quantized Variational Autoencoder, or VQ-VAE, has emerged as a pivotal architecture in discrete representation learning by introducing a process of tokenization to the latent space. Instead of continuous vectors, VQ-VAEs learn a finite set of discrete embeddings – a ‘codebook’ – and represent data as the closest embedding from this codebook. This discretization not only compresses information but also aligns remarkably well with the strengths of Transformer networks, which excel at processing sequential, discrete data. By converting complex data into sequences of tokens, VQ-VAEs enable Transformers to model long-range dependencies and generate high-quality samples, driving advancements in areas like image, audio, and video generation. The resulting discrete latent spaces facilitate efficient learning and provide a powerful framework for exploring the underlying structure of complex datasets, establishing VQ-VAE as a foundational element in modern generative modeling.

The Ghost in the Machine: Codebook Collapse

Codebook collapse in Vector Quantized Variational Autoencoder (VQ-VAE) training manifests as the underutilization of learned codebook entries; specifically, a disproportionately small number of codes within the discrete codebook consistently represent a significant portion of the input data. During training, the model effectively ignores a large fraction of the available codes, leading to a reduced capacity for representing the full data distribution. This phenomenon is observed through monitoring code usage frequencies, revealing a skewed distribution where a few codes dominate while the majority remain rarely or never activated. The consequence is a loss of representational power and limits the model’s ability to reconstruct or generate diverse outputs, as it cannot effectively leverage the full capacity of the codebook.

Codebook collapse limits the representational capacity of the Vector Quantized Variational Autoencoder (VQ-VAE) by effectively reducing the dimensionality of the information bottleneck. When a significant portion of the codebook remains unused during both encoding and decoding, the model fails to leverage the full potential of the discrete latent space. This diminished capacity restricts the model’s ability to accurately represent and reconstruct the intricacies present within the training data distribution, leading to a loss of detail and potentially hindering downstream tasks that rely on a comprehensive latent representation. Consequently, the model’s generalization performance and its ability to capture subtle variations in the input data are compromised.

The Straight-Through Estimator (STE) addresses the issue of non-differentiability in Vector Quantized Variational Autoencoders (VQ-VAEs) by approximating the gradient through the discrete quantization step; however, STE does not guarantee uniform codebook utilization. While enabling gradient propagation, STE can still result in a scenario where a limited number of codebook entries are consistently selected during both encoding and decoding. This occurs because the gradient signal, though present, may not be sufficient to incentivize the model to explore and utilize the entire codebook space, leading to a disproportionate reliance on a subset of the available codes and hindering the model’s representational capacity. The problem isn’t a lack of gradient flow, but rather the effectiveness of that gradient in preventing code specialization and encouraging diversity in code usage.

Reclaiming Control: VP-VAE – Decoupling and Perturbation

Vector-Quantized Variational Autoencoders (VP-VAEs) mitigate codebook collapse-a common issue where only a subset of codebook entries are utilized during training-by initially learning a continuous representation prior to the quantization step. Traditional VQ-VAEs discretize the latent space early in the process, forcing the encoder to map to a fixed, and potentially uninformative, codebook. In contrast, VP-VAEs first train an autoencoder to establish a meaningful latent space, and only subsequently introduce the vector quantization bottleneck. This approach allows the encoder to learn representations that are better suited to the data distribution before being constrained by the discrete codebook, thereby improving utilization of the codebook and preventing collapse.

To enhance the robustness of the learned latent space, VP-VAE employs Non-Parametric Density Estimation (NPDE) and Metropolis-Hastings Sampling. NPDE is used to model the distribution of latent vectors without assuming a specific parametric form, allowing for flexible representation of data density. Metropolis-Hastings Sampling then leverages this density estimate to generate perturbations in the latent space; proposed samples are accepted or rejected based on their likelihood under the NPDE-estimated distribution, effectively exploring the latent space around existing vectors. This process introduces controlled noise, encouraging the model to learn more generalized and less brittle representations by exposing it to variations of the input data during training.

A low-dimensional quantization bottleneck is incorporated into the VP-VAE architecture to enforce a more compact and refined latent representation. This bottleneck operates by mapping the continuous latent vectors to a discrete, lower-dimensional space, achieved through techniques such as k-means clustering or vector quantization. By restricting the information flow through this bottleneck, the model is compelled to learn more efficient and discriminative features, mitigating redundancy and enhancing generalization performance. The dimensionality of this bottleneck is a hyperparameter that controls the level of compression and can be adjusted to balance reconstruction accuracy and representational capacity.

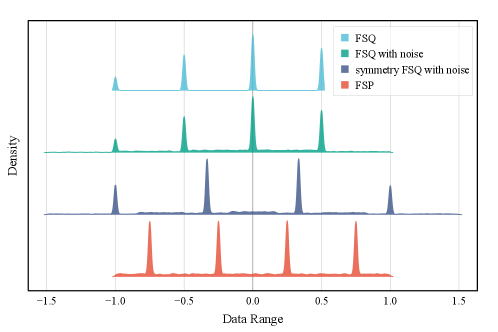

The Pursuit of Uniformity: FSP – Efficient Learning

Following the Variational Probabilistic Variational Autoencoder (VP-VAE) framework, the Feature Space Perturbation (FSP) method operates under the assumption of a uniform distribution within the latent space. This foundational principle significantly simplifies the perturbation process inherent in VP-VAE by removing the need to sample from a complex, potentially multimodal distribution. Instead of relying on probabilistic sampling, FSP can directly and uniformly perturb points within the defined latent space, reducing computational demands and streamlining the process of generating perturbed latent vectors for robust feature learning. This simplification is crucial for scaling FSP to high-dimensional data and complex models.

K-Means Clustering is employed in Feature Space Perturbation (FSP) to create a codebook, representing discrete latent variables, with improved computational efficiency. This process utilizes the Lloyd-Max algorithm, an iterative refinement technique, to identify cluster centroids – points representing the mean of data within each cluster. Specifically, the algorithm alternates between assigning data points to the nearest centroid and recalculating the centroid positions based on the assigned points, converging on optimal cluster centers. These centroids then serve as the codebook elements, enabling discrete latent space representation and simplifying the perturbation process by reducing the search space for optimal perturbations.

The assumption of a uniform distribution within the latent space, central to the Function Space Perturbation (FSP) method, directly translates to reduced computational demands during the learning process. This simplification obviates the need for complex calculations typically associated with non-uniform distributions when determining optimal perturbations. Specifically, the uniformity allows for efficient sampling and evaluation of latent variables, decreasing the overall computational cost without compromising the model’s ability to generalize to unseen data. Robust learning is maintained because the uniform prior encourages exploration of the entire latent space, preventing the model from becoming overly reliant on specific regions and thus improving its resilience to noise and variations in input data.

Echoes of Reality: Validation and Impact

The developed methodology consistently yielded gains in both audio and image generation, representing a notable advancement in generative modeling. Rigorous testing across diverse datasets showcased an ability to synthesize higher-fidelity content compared to existing techniques. This improvement isn’t merely quantitative; evaluations reveal a perceptible increase in perceptual quality, meaning the generated audio and images are not only closer to the original data based on objective metrics, but also more naturally perceived by listeners and viewers. The approach effectively addresses common artifacts and distortions often associated with generative models, resulting in outputs that are demonstrably more realistic and aesthetically pleasing, paving the way for applications demanding high-quality synthesized media.

Rigorous evaluation employing established perceptual quality metrics – including STOI for audio, PESQ for speech, and LPIPS for both modalities – demonstrates a significant enhancement in generated content. Notably, image quality, as quantified by Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR), reached 24.19 with a kernel size of 1024, representing the highest performance attained throughout the experimental process. This result indicates a marked improvement in visual fidelity and detail preservation. The achieved scores across these metrics collectively confirm the method’s ability to produce outputs that are not only technically accurate but also perceptually pleasing, offering a substantial advancement in generative model performance.

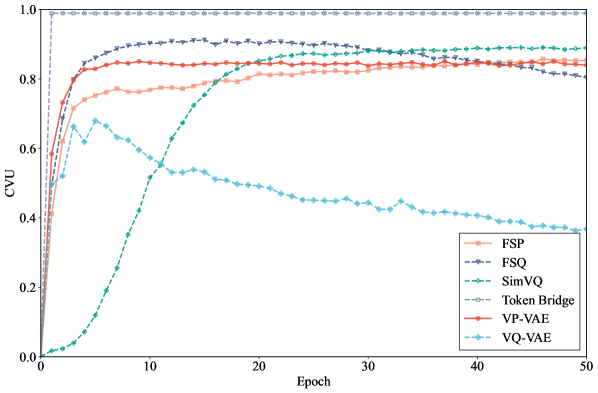

Evaluations reveal a compelling synergy between structural fidelity and perceptual quality; the approach achieves a Structural Similarity Index (SSIM) of 0.778 with a codebook size of 4096, indicating strong preservation of image details. Critically, this performance is coupled with a competitive Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity (LPIPS) score of 0.21, suggesting a high degree of perceptual realism. Unlike conventional Vector Quantized-Variational Autoencoders (VQ-VAE) which often suffer from codebook instability, this method maintains a stable codebook valid usage (CVU) of 0.88. Complementing these visual results, the approach also demonstrates exceptional audio quality, attaining a Short-Time Objective Intelligibility (STOI) score of 0.9225 with a codebook size of 16384, positioning it as a leading performer in objective audio evaluations.

The pursuit of discrete representation learning, as detailed in this work, inherently involves a dance with instability. VP-VAE attempts to navigate this through adaptive vector perturbation, effectively re-framing quantization as a controlled disturbance within the latent space. This echoes the sentiment expressed by Carl Friedrich Gauss: “I prefer a beautiful model to a complex one.” The elegance of VP-VAE lies in its simplification – by decoupling representation learning from direct codebook optimization, it seeks a more stable, and therefore ‘beautiful,’ solution. The method’s success stems from recognizing that imposing order – or, in this case, discrete codes – requires a nuanced understanding of the underlying perturbations and a willingness to test the boundaries of conventional quantization techniques.

What Breaks Next?

The VP-VAE proposes a fascinating, if subtle, shift: treat the quantization step not as an optimization target, but as a controlled disturbance. This decoupling is a useful provocation. It sidesteps the notorious codebook collapse, certainly, but it merely relocates the problem. One suspects the true instability doesn’t reside within the codebook itself, but in the very act of forcing a continuous space into discrete bins. Future work should rigorously examine the information lost – or, more interestingly, the information created – by this enforced discontinuity. Is the resulting latent space truly a useful representation, or merely a convenient compression?

The current framework relies on perturbation as a corrective measure. Yet, perturbation is, at its core, a form of ignorance – a brute-force attempt to explore a space without true understanding. A more elegant solution would predict, rather than react to, the consequences of quantization. Could adversarial training, or perhaps techniques borrowed from non-parametric density estimation, allow a model to anticipate and mitigate the distortions inherent in discrete representation learning?

Ultimately, the success of VP-VAE, or its successors, will hinge not on achieving marginal gains in reconstruction error, but on demonstrating a genuinely novel capability unlocked by this alternative approach. The field requires a demonstration that this isn’t simply a more stable way to compress data, but a method for discovering and exploiting previously inaccessible structure within it. Only then will the perturbation become illumination.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.17133.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Poppy Playtime Chapter 5: Engineering Workshop Locker Keypad Code Guide

- Jujutsu Kaisen Modulo Chapter 23 Preview: Yuji And Maru End Cursed Spirits

- God Of War: Sons Of Sparta – Interactive Map

- 8 One Piece Characters Who Deserved Better Endings

- Who Is the Information Broker in The Sims 4?

- Poppy Playtime 5: Battery Locations & Locker Code for Huggy Escape Room

- Mewgenics Tink Guide (All Upgrades and Rewards)

- Pressure Hand Locker Code in Poppy Playtime: Chapter 5

- Poppy Playtime Chapter 5: Emoji Keypad Code in Conditioning

- I Used Google Lens to Solve One of Dying Light: The Beast’s Puzzles, and It Worked

2026-02-21 13:54