Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research delves into the behavior of localized energy concentrations-Q-balls and Q-shells-within an extended theoretical framework.

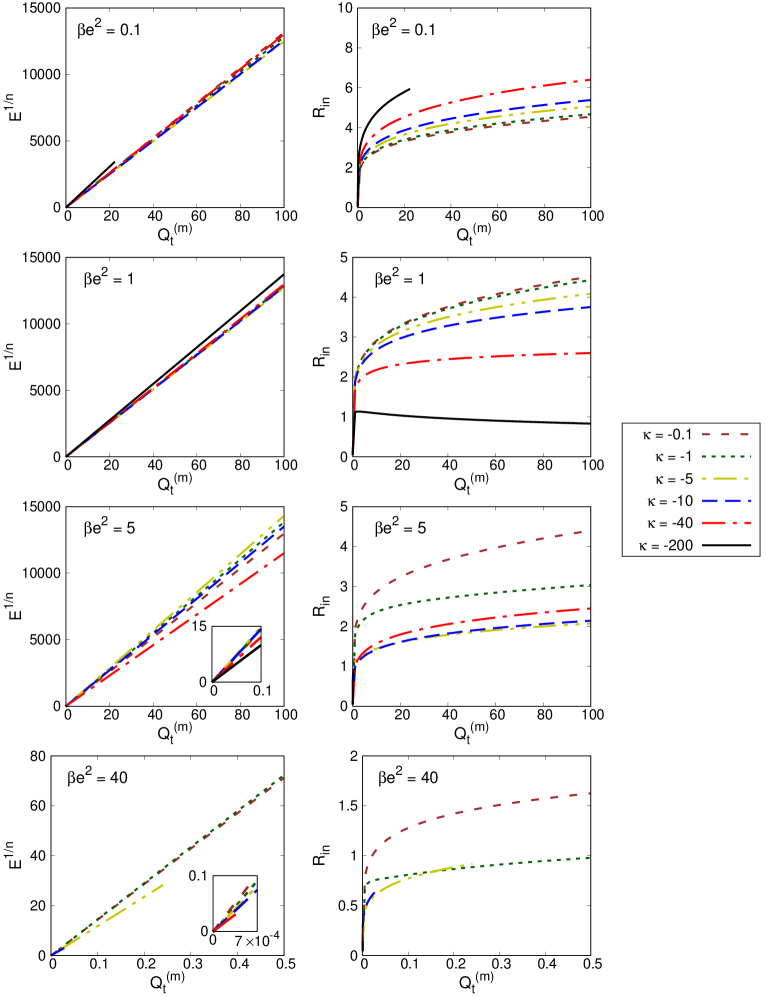

This study investigates the impact of quartic interactions on the compactness and stability of Q-ball and Q-shell solutions within a $CP^N$ Skyrme-Faddeev model.

Despite the well-established existence of finite-energy compact Q-ball and Q-shell solutions in CP^N models with analytic potentials, their behavior within more complex Lagrangian frameworks remains an open question. This work, ‘Compact Q-balls and Q-shells within a $CP^N$ Skyrme-Faddeev type model’, investigates these non-topological solitons within an extended Skyrme-Faddeev model incorporating quartic derivative terms, revealing that harmonic time dependence and these quartic terms independently circumvent Derrick’s scaling argument. We find that these interactions significantly modify energy density profiles and influence the stability of resulting compactons, specifically altering the E(Q) relationship between energy and Noether charge. How might these findings inform the construction of more realistic models of compact boson stars and their astrophysical implications?

The Illusion of Stability: Confining Energy in a Chaotic Universe

Many physical systems are best represented not by waves that extend indefinitely, but by disturbances that are sharply confined in space. Traditional soliton solutions, while remarkably stable due to their topological properties, often present a challenge in these scenarios, as they typically lack this finite spatial extent; their tails, though diminishing, theoretically stretch to infinity. This limitation hinders their application in modeling phenomena where localization is paramount, such as certain types of pulse propagation or the behavior of defects in condensed matter. Consequently, researchers have been driven to explore alternative wave-like structures – those that not only maintain stability but also exhibit a definitive boundary, effectively confining the energy within a finite region. The pursuit of such localized solutions has led to investigations beyond the conventional framework of topological stability, opening avenues for exploring more complex and nuanced wave dynamics.

Unlike traditional solitons which theoretically extend infinitely in space, compactons present a strikingly different behavior – they are finite, localized disturbances. This characteristic arises from a unique mathematical property: at their boundaries, not only does the field itself diminish to zero, but so too does its rate of change, the derivative. This ‘vanishing derivative’ condition is crucial; it prevents the usual dispersive spreading that plagues many wave-like solutions and ensures the compacton remains truly localized, offering a compelling advantage in modeling physical phenomena where finite-sized disturbances are essential. The consequence is a wave packet that propagates without changing shape or dispersing, maintaining a definitive spatial boundary – a feature absent in many conventional wave solutions and opening new avenues for describing complex systems.

The emergence of compacton solutions necessitates a departure from conventional mathematical approaches centered on topological stability. While solitons are typically characterized by their robustness stemming from conserved topological charges, compactons derive their finite extent from a delicate balance of nonlinear and dispersive effects – a realm where traditional topological arguments fall short. Investigating these solutions requires advanced techniques in nonlinear analysis, often involving modified Korteweg-de Vries equations and the exploration of higher-order nonlinearities. The mathematical framework must account for the precise conditions under which these localized structures can form and propagate, demanding careful consideration of dispersion relations, stability analyses, and the interplay between different spectral components – all to fully characterize their unique behavior and potential applications in modeling wave phenomena.

The Lagrangian Framework: A Description, Not a Foundation

The Lagrangian density, denoted as \mathcal{L}, fully describes the dynamics of a scalar field \phi(x). It is constructed as the difference between the kinetic energy term and the potential energy term. For a scalar field, the kinetic energy is typically expressed as \frac{1}{2} \partial_{\mu} \phi \partial^{\mu} \phi, representing the energy associated with the field’s time and spatial derivatives. The potential energy, V(\phi), defines the field’s inherent energy based on its value and governs its self-interactions. The total Lagrangian is therefore given by \mathcal{L} = \frac{1}{2} \partial_{\mu} \phi \partial^{\mu} \phi - V(\phi). Applying the Euler-Lagrange equation to this Lagrangian yields the field equation, which dictates the time evolution and spatial behavior of the scalar field.

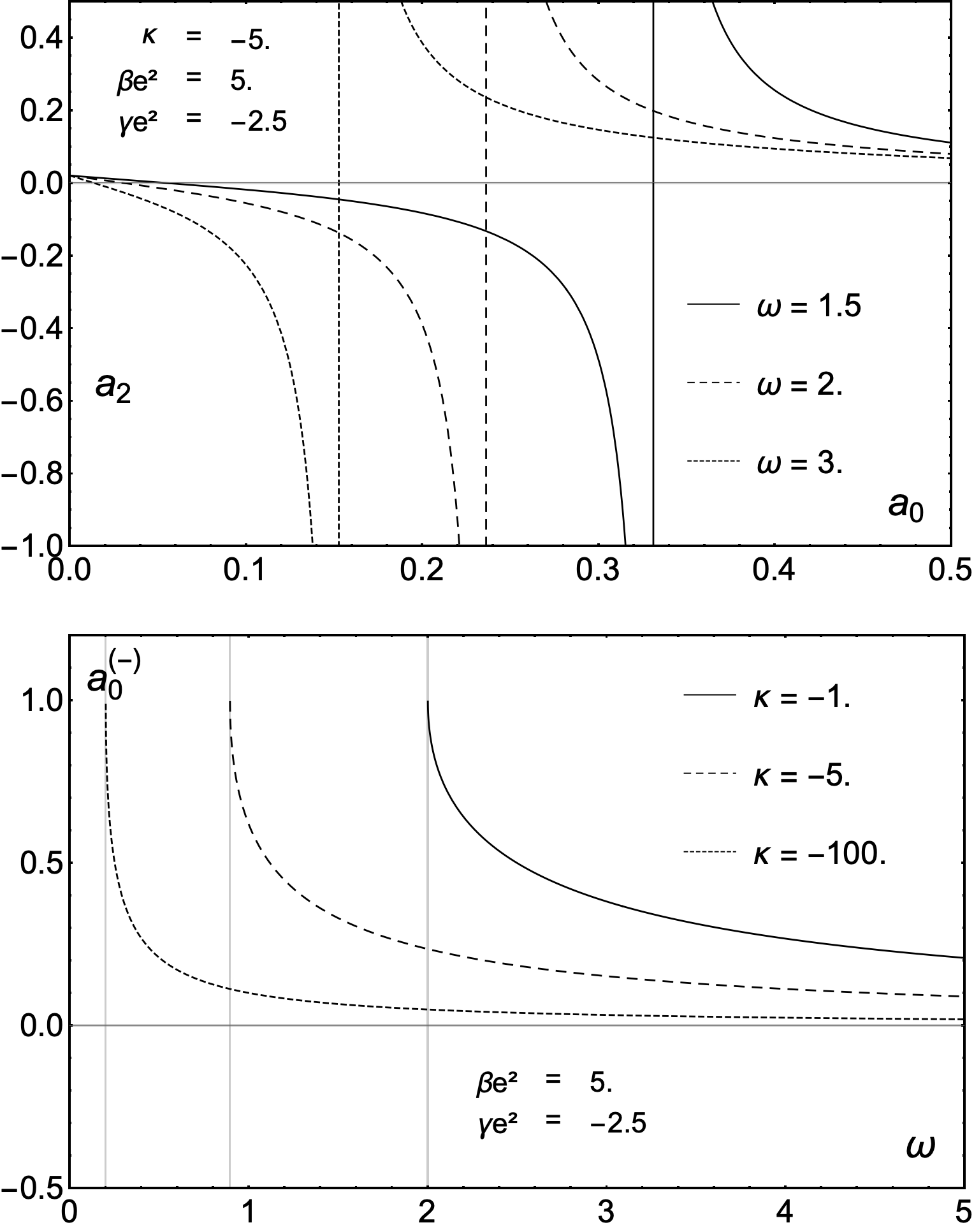

The inclusion of quartic terms, expressed as \lambda \phi^4 , within the Lagrangian density fundamentally alters the field’s self-interaction. These terms represent a four-point interaction, impacting the energy density and, consequently, the effective potential experienced by the field. A positive λ value generally promotes instability and can lead to spontaneous symmetry breaking, while a negative value can enhance stability but introduce new types of solutions. The presence of these interactions is critical in determining the properties of compact solutions such as solitons or Q-balls, specifically influencing their size, mass, and overall stability against perturbations. Modifications to the quartic term’s coefficient directly affect the binding energy and the conditions under which these localized structures can exist.

Spherical harmonics, denoted as Y_{l}^{m}(\theta, \phi), provide a complete and orthonormal basis for functions defined on the surface of a sphere. Their application to scalar field analysis arises from the inherent spherical symmetry present in many physical systems. By expanding the field’s angular dependence in terms of these harmonics, the partial differential equation governing the field’s behavior can be decomposed into a series of ordinary differential equations, one for each l and m value. This simplification significantly reduces the complexity of the problem, allowing for analytical or numerical solutions that would otherwise be intractable. The quantum numbers l and m define the total angular momentum and its z-component, respectively, and determine the symmetry properties of each harmonic component of the field.

Mapping the Boundaries: Extracting Solutions from the Radial Equation

The radial equation is a second-order ordinary differential equation obtained through a variational approach utilizing the Lagrangian formalism. Specifically, applying the Euler-Lagrange equation to the Lagrangian, which describes the energy of the field, yields the radial equation that governs the behavior of the field as a function of radial distance. This equation dictates how the field varies spatially and is fundamental in determining solutions that satisfy boundary conditions, particularly those defining compactness. The form of the radial equation depends on the specific Lagrangian and the field in question, but its solution, denoted as a radial function f(R), directly determines the spatial distribution and overall characteristics of the field.

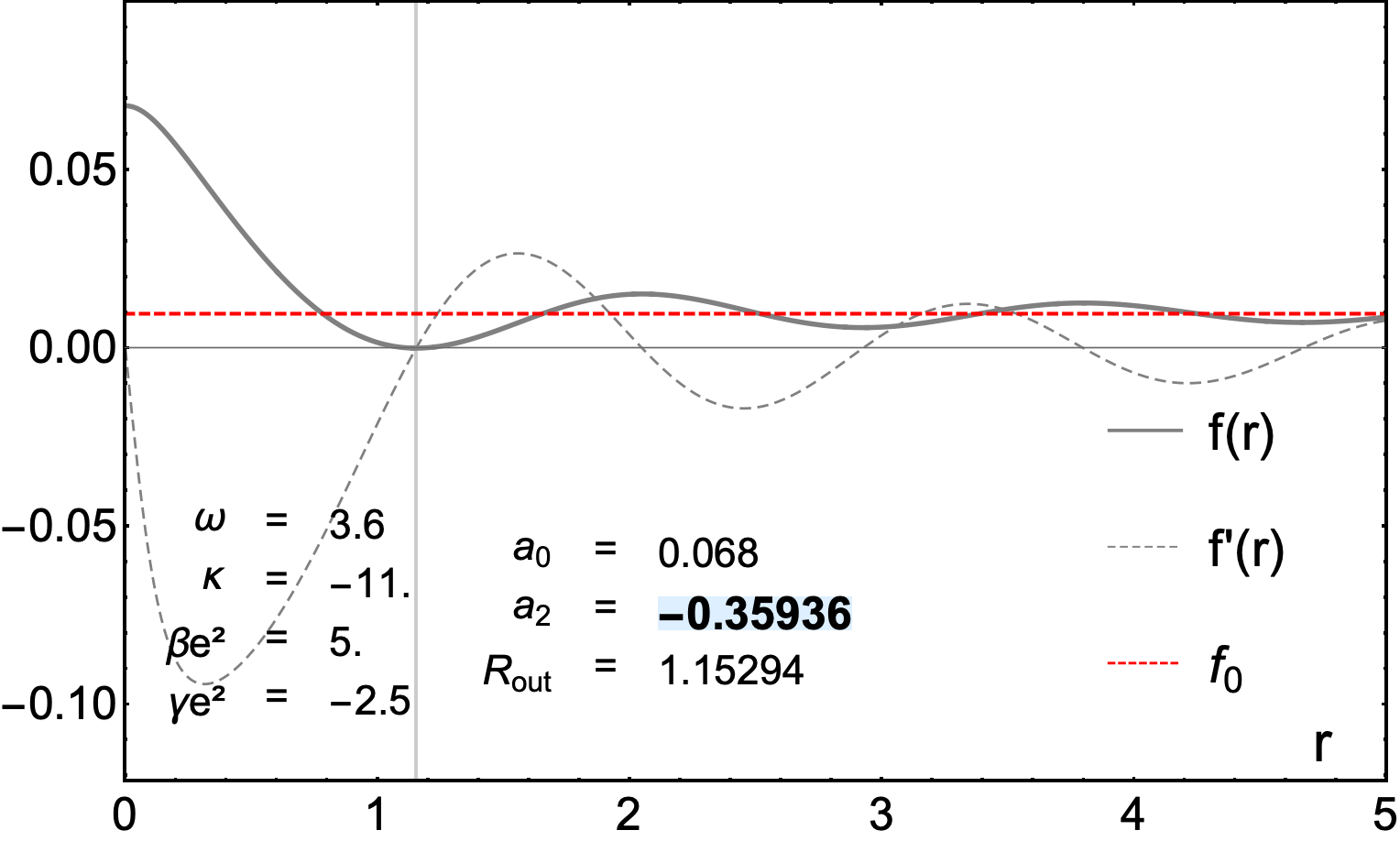

A power series expansion of the radial function, f(r) = \sum_{n=0}^{\in fty} a_n r^n, provides an analytical solution applicable when the potential allows. This method is particularly useful for analyzing the function’s behavior close to the origin (r = 0), where the series converges if the coefficients a_n are appropriately bounded. The coefficients are determined by substituting the series expansion into the radial equation and solving the resulting recurrence relation. While providing an approximate solution, the power series method reveals key characteristics such as the singularity at the origin and allows for the determination of the function’s derivatives and integrals without direct solution of the differential equation.

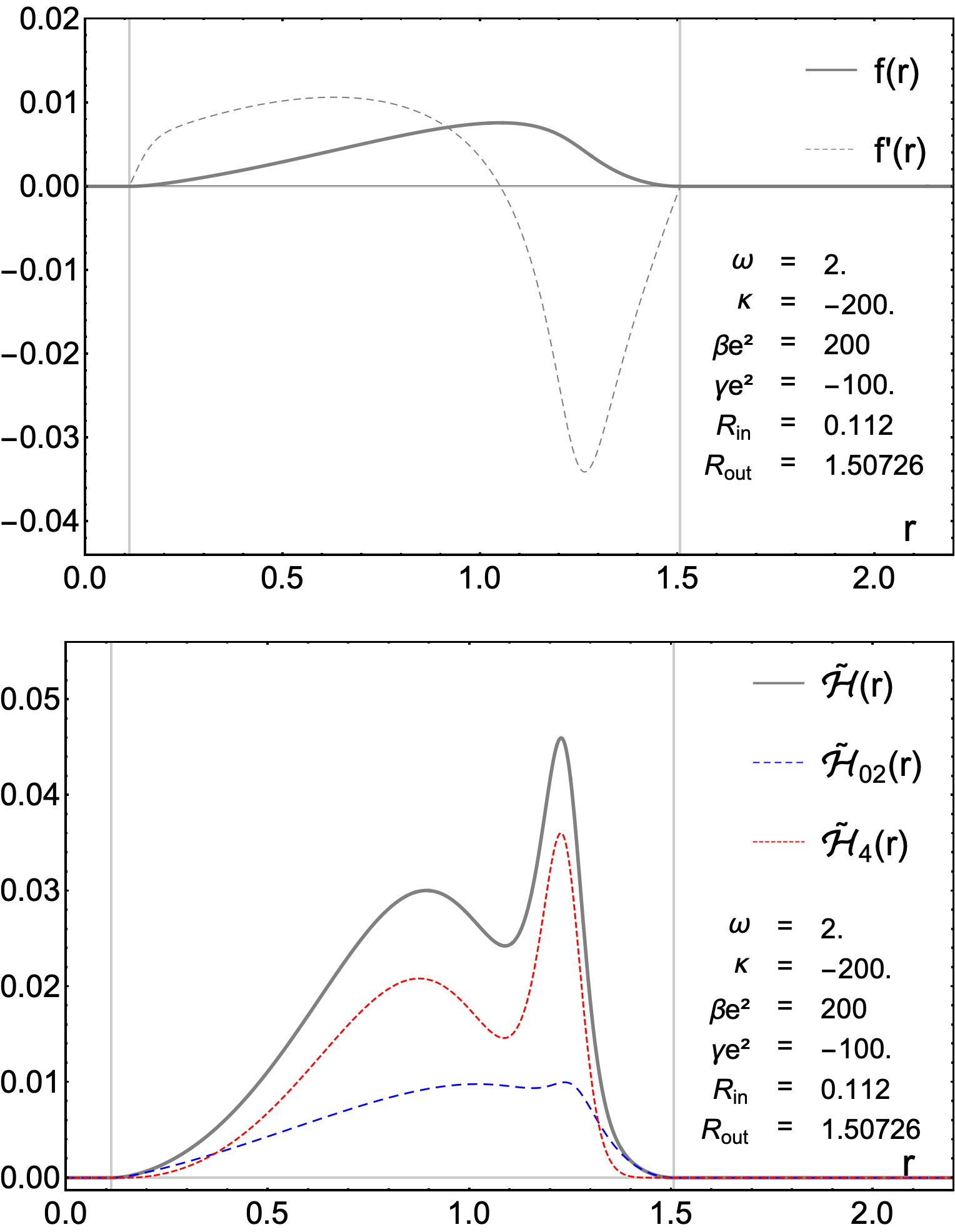

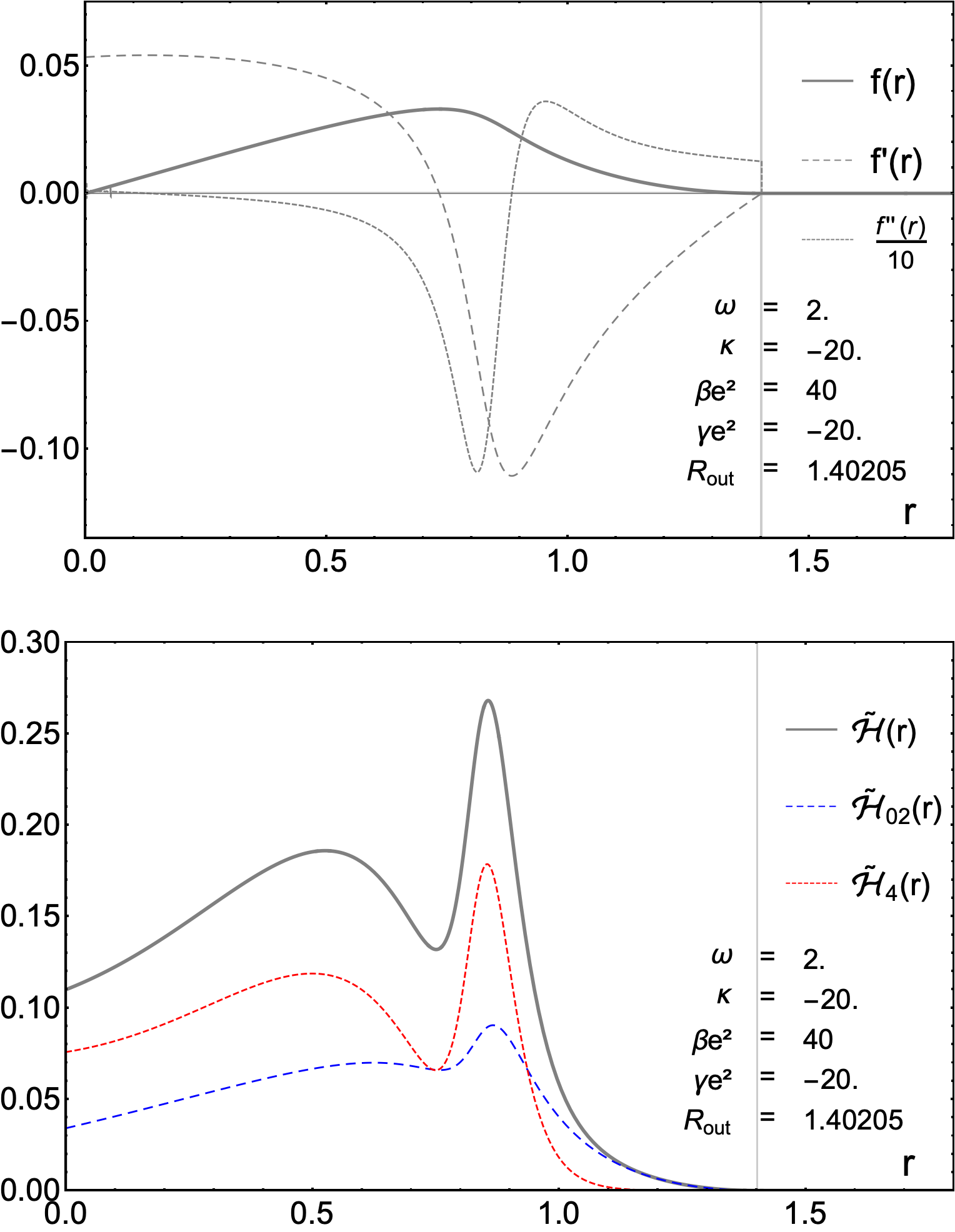

The shooting method is a numerical technique used to solve the radial equation by iteratively refining initial conditions. This approach involves integrating the radial equation from an initial point – typically near the origin – and adjusting the initial value of the radial function f(0) and its derivative f'(0) until the solution satisfies specified boundary conditions at an outer radius, R_{out}. Specifically, the values of the initial parameters are adjusted to force both the radial function f(R_{out}) and its first derivative f'(R_{out}) to equal zero at R_{out}, effectively defining a valid solution to the radial equation and establishing the spatial extent of the field.

Q-balls and Q-shells: Impermanence Masquerading as Stability

Q-balls are spatially localized, finite-energy soliton-like configurations arising in field theories possessing a conserved U(1) Noether charge. Unlike topological solitons which rely on topological boundary conditions for stability, Q-balls are non-topological, meaning their stability stems directly from the minimization of energy given a fixed Noether charge. This is achieved when the energy E scales with the Noether charge Q as E \sim Q^{\alpha}, where \alpha > 1 ensures that decay into free particles carrying the Noether charge is energetically unfavorable, thus providing a stable, localized solution. The Noether charge effectively acts as a “winding number” preventing the solution from unraveling, even without topological protection.

Q-shells represent an extension of soliton concepts by incorporating a spatially dependent structure characterized by a hollow spherical interior. Unlike traditional solitons which are typically compact, Q-shells possess a finite radius defining an inner void, and a non-zero field value within that space. This internal cavity differentiates Q-shells, requiring a more complex treatment of their field configurations and stability criteria compared to uniformly distributed solitons or Q-balls. The existence of this hollow region introduces additional degrees of freedom in the solution, and modifies the energy-charge relationship necessary to maintain stability; while still governed by the principle of a conserved Noether charge, the energy E scales with the charge Q and a parameter δ such that E \sim Q\delta, where δ accounts for the altered spatial distribution.

The stability of both Q-balls and Q-shells is fundamentally determined by the relationship between their energy, E, and the conserved Noether charge, Q. This relationship is expressed as E \sim Q\delta, where δ represents a dimensionless coefficient. For a solution to be stable and prevent decay into free particles, this coefficient must be less than one (\delta < 1). If δ were greater than or equal to one, the energy would scale at least linearly with the charge, allowing for unstable configurations susceptible to fragmentation and dissolution, as the Noether charge would not sufficiently lower the energy to create a bound state.

The ESF Model: A Framework for Predicting Inevitable Decay

The ESF model represents a significant advancement in the theoretical study of non-topological solitons, specifically compact Q-balls and Q-shells exhibiting extended dynamical behavior. Building directly upon the established CPN model, it introduces crucial modifications that allow for a more detailed and nuanced exploration of these complex objects. This framework isn’t simply a refinement; it provides the mathematical tools necessary to investigate the intricate interplay between energy density and spatial distribution within these compactons. By incorporating additional parameters and allowing for a broader range of potential interactions, the ESF model facilitates the analysis of stability, oscillation modes, and ultimately, the potential role these structures might play in various high-energy physics scenarios, moving beyond the limitations of simpler models and opening avenues for predicting their behavior in more realistic conditions.

The ESF model distinguishes itself through the strategic inclusion of quartic terms and a carefully defined potential within its mathematical framework. These additions move beyond simpler models by allowing for a more detailed and nuanced exploration of the solutions’ characteristics – specifically, how these compact Q-balls and Q-shells behave under varying conditions. The potential, coupled with the quartic terms, introduces complexities that reflect the self-interaction of the scalar field, enabling researchers to investigate the stability, shape, and dynamics of these non-topological solitons with greater precision. This refined approach provides a more realistic and comprehensive understanding of their properties, potentially revealing subtle behaviors previously obscured by less sophisticated models and opening avenues for predicting their existence and characteristics in more complex theoretical landscapes – a capability crucial for bridging the gap between theoretical predictions and potential observational evidence.

The ESF model furnishes a platform to investigate the physical consequences of compactons – localized, extended solitons – within diverse theoretical landscapes. Researchers can now probe how these structures behave and interact, guided by key parameters such as b_2 = \mu^2/16 and b_3 = \mu^2/(24*R_{out}), which dictate the shape and stability of the compacton solutions. These coefficients, intrinsically linked to the model’s potential, allow for precise control over the system’s characteristics and enable explorations into areas like non-perturbative effects, soliton collisions, and potential applications in areas beyond standard model physics. Future studies employing this framework promise to illuminate the role of compactons in complex dynamical systems and offer insights into the fundamental nature of soliton phenomena.

The pursuit of stable, localized solutions within field theories, as demonstrated by this study of Q-balls and Q-shells, feels less like construction and more like observing a natural phenomenon. The model, with its quartic interactions, doesn’t grant stability; it merely reveals the conditions under which it emerges. It’s a delicate balance, a fleeting arrangement of energy density. As Marie Curie once noted, “Nothing in life is to be feared, it is only to be understood.” This sentiment resonates deeply; the work doesn’t impose order, but seeks to decipher the inherent properties that allow these compact structures to briefly resist the inevitable decay towards lower energy states, observing rather than commanding their existence.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The persistence of compactness, even within models deliberately constructed to allow for its dissolution, suggests a fundamental principle at play-less a matter of mathematical convenience and more a consequence of the system seeking its own minimal energy state. The quartic interactions explored here do not prevent decay, merely sculpt its form. Monitoring this decay, then, is the art of fearing consciously; each unraveling is not a bug, but a revelation of the model’s true boundaries.

Future work must address the limitations of static solutions. The true test of these configurations lies in their dynamics – how they respond to perturbations, how they interact, and ultimately, how they fail. A complete understanding demands a move beyond idealized scenarios, embracing the inherent instability of complex systems. True resilience begins where certainty ends.

Furthermore, the connection to physical systems remains largely speculative. Translating these mathematical constructions into empirically verifiable predictions will require confronting the messy realities of quantum field theory and the formidable challenges of non-perturbative calculations. The search for compactons may not yield a new particle, but a new way of understanding the language of stability itself.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.15276.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Enshrouded: Giant Critter Scales Location

- All Carcadia Burn ECHO Log Locations in Borderlands 4

- All Shrine Climb Locations in Ghost of Yotei

- Best ARs in BF6

- Best Finishers In WWE 2K25

- Top 8 UFC 5 Perks Every Fighter Should Use

- Top 10 Must-Watch Isekai Anime on Crunchyroll Revealed!

- Scopper’s Observation Haki Outshines Shanks’ Future Sight!

- Poppy Playtime 5: Battery Locations & Locker Code for Huggy Escape Room

- How to Unlock & Visit Town Square in Cookie Run: Kingdom

2026-02-18 13:23