Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research delves into the fundamental patterns of particle creation when protons collide with oxygen nuclei at high energies.

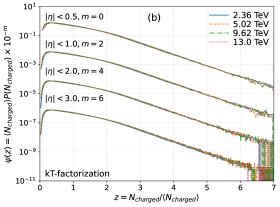

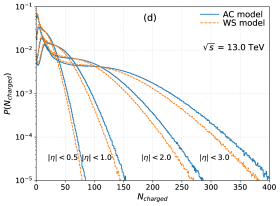

This study compares predictions from Pythia and kTk-factorization, analyzing multiplicity distributions and validating KNO scaling with double Negative Binomial Distributions for various nuclear structures.

Understanding particle production in high-energy collisions remains a central challenge in relativistic heavy-ion physics, yet accurately modeling these events requires detailed knowledge of both the underlying dynamics and the initial nuclear configuration. This study, ‘A study of charged-particle multiplicity distribution in high energy p-O collisions’, investigates charged particle production in proton-oxygen collisions using the Pythia and k_T-factorization frameworks, finding that different geometric descriptions of the oxygen nucleus-specifically, alpha-cluster versus Woods-Saxon distributions-significantly impact predicted multiplicities, especially at high pseudorapidity. Moreover, the analysis, which spans center-of-mass energies from 2.36 to 13.0 TeV and utilizes tools like the double Negative Binomial Distribution to parameterize results, reveals discrepancies between the two modeling approaches; what does this suggest about the relative importance of soft and semi-hard processes, and how can these models be refined for more accurate predictions?

Uncertainty in the Nucleus: Modeling for Extreme Conditions

The fidelity of heavy-ion collision simulations hinges on the accuracy with which the colliding nuclei are modeled, and the oxygen nucleus presents a particular challenge. Traditional approaches frequently treat the nucleus as a uniform density distribution, or rely on simplified parameterizations to reduce computational load. However, this simplification overlooks the nuanced arrangement of protons and neutrons within the nucleus-a structure far from homogenous. Consequently, these assumptions can introduce significant errors in predicting collision outcomes, particularly in scenarios sensitive to the nuclear shape and internal dynamics. Achieving a more realistic representation of the oxygen nucleus, therefore, is paramount for refining these simulations and extracting meaningful insights into the behavior of nuclear matter under extreme conditions.

The density of nucleons – protons and neutrons – within an atomic nucleus is far from uniform, presenting a significant challenge to accurate modeling. Traditional approaches often treat the nucleus as a smoothly distributed, consistent fluid, which simplifies calculations but obscures crucial details of its structure. In reality, nucleons aren’t evenly spread; instead, they exhibit complex distributions influenced by quantum mechanical effects and strong nuclear forces. This non-uniformity manifests as density fluctuations and localized concentrations, particularly near the nuclear surface. Consequently, simulations relying on uniform density models can introduce substantial errors, especially when studying phenomena sensitive to the nucleus’s shape and internal structure. A more realistic depiction demands representations that accommodate these variations, requiring computational techniques capable of handling the intricacies of nucleon arrangement and interactions within the nuclear volume.

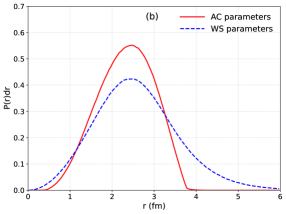

The Alpha-Cluster Model proposes a fundamentally different approach to understanding nuclear structure, envisioning the nucleus not as a uniform fluid of nucleons, but as an assembly of alpha particles – helium nuclei composed of two protons and two neutrons. This perspective acknowledges the strong nuclear force’s tendency to bind nucleons into these stable alpha clusters, potentially offering a more accurate depiction of nuclear density, particularly in lighter nuclei. While traditional models often simplify the nucleon distribution for computational ease, the Alpha-Cluster Model embraces this inherent complexity, albeit at a significant cost. Simulating the interactions between numerous, distinct alpha particles demands substantially greater computational resources compared to methods employing smoother, averaged density distributions. Nevertheless, this increased demand may be justified by the potential for greater fidelity in modeling nuclear reactions and the behavior of matter under extreme conditions, such as those found in heavy-ion collisions.

Accurately portraying the arrangement of protons and neutrons within a nucleus demands more than simple, uniform models. Nuclear density isn’t evenly spread; instead, it exhibits a characteristic shape with a distinct core and a gradual fall-off towards the nuclear surface. To mathematically represent this complex distribution, scientists employ continuous functions, notably the Woods-Saxon distribution. This function, characterized by its parameters – radius and diffuseness – allows for a smooth, realistic depiction of nucleon density. The radius defines the overall size of the nucleus, while the diffuseness parameter governs how sharply the density drops off at its periphery. By carefully adjusting these parameters, the Woods-Saxon distribution effectively models the nuanced arrangement of nucleons, providing a crucial foundation for theoretical calculations and simulations of nuclear behavior.

Simulating the Collision: A Multi-Layered Approach

Pythia is a widely-used Monte Carlo event generator employed in high-energy physics to simulate particle collisions. While capable of modeling fundamental interactions, accurate representation of collisions involving nuclei necessitates the inclusion of detailed nuclear models. These models provide information regarding the nucleon density distribution within the nucleus, as well as the correlations between nucleons, which significantly affect the collision dynamics. Without these nuclear inputs, Pythia’s simulations will fail to accurately predict experimental observables, such as particle multiplicities and transverse momentum distributions, as the underlying nuclear structure is not accounted for in the collision process. The precision of the simulation, therefore, is directly linked to the quality and sophistication of the incorporated nuclear model.

The Angantyr model within the Pythia event generator is dedicated to simulating high-energy collisions involving nuclei. It achieves this by utilizing foundational nuclear density representations, specifically the nuclear parton distribution function (nPDF) and the corresponding saturation scale Q_s. These densities define the probability of finding partons within the nucleus and their momentum distribution. Angantyr employs these nPDFs to generate initial state partons, effectively modeling the internal structure of the colliding nuclei. The model then evolves these partons through the collision, accounting for multiple parton interactions and hadronization to produce final-state particles. Accurate representation of these initial densities is crucial for predicting collision observables and comparing simulations to experimental data from heavy-ion collisions.

Accurate simulation of high-energy nuclear collisions necessitates accounting for the inherent transverse momentum of participating partons, known as Initial Transverse Momentum (ITM). Partons, such as quarks and gluons, are not static within the colliding nuclei; they possess an intrinsic momentum perpendicular to the beam axis. Ignoring this ITM leads to an underestimation of the collision’s energy density and an inaccurate representation of the produced particles. The magnitude of ITM is typically characterized by a Gaussian distribution with a variance proportional to \langle k_T^2 \rangle , where k_T represents the transverse momentum. Precise determination of \langle k_T^2 \rangle is crucial for realistic collision modeling and relies on theoretical frameworks like the kT-factorization approach and connections to the Color Glass Condensate, which describe the internal momentum distributions within the nuclei.

The kT-factorization framework addresses the inclusion of initial transverse momentum (p_{T}) in particle production during heavy-ion collisions. This framework posits that particle production can be described as a convolution of incoming partons with a non-perturbative unintegrated parton distribution function (UPDF). These UPDFs inherently include information about the intrinsic p_{T} of the partons, arising from multiple interactions within the nucleus. The framework ultimately connects to the Color Glass Condensate (CGC) theory by providing a consistent description of these initial conditions, where the CGC describes the high-density partonic system within the nucleus and accounts for gluon saturation effects that influence the UPDFs and, consequently, the observed particle distributions.

Dissecting Particle Production: Statistical Signatures

Charged-particle multiplicity, representing the total number of charged particles created in heavy-ion collisions, serves as a fundamental observable for characterizing the collision dynamics and the properties of the resulting matter. This quantity is determined experimentally through particle tracking and identification within the detector system, summing the counts of all detected charged particles – including pions, kaons, protons, and electrons. The measured multiplicity is highly sensitive to the collision energy, the impact parameter between the colliding nuclei, and the underlying nuclear equation of state. Analyzing the distribution of this multiplicity, rather than just its average value, provides crucial insights into the fluctuations present in the particle production process and helps constrain theoretical models of nuclear interactions. N_{ch} is often used to denote the charged-particle multiplicity.

The observed charged-particle multiplicity in heavy-ion collisions exhibits fluctuations that deviate from the predictions of a simple Poisson distribution, which assumes a constant mean and variance. Specifically, experimental data consistently demonstrates a variance exceeding the mean, indicating overdispersion. The Negative Binomial Distribution (NBD) addresses this by introducing an additional parameter, k, representing the number of independent sources contributing to particle production. This parameter effectively allows for a variance greater than the mean, providing a more accurate statistical description of the observed multiplicity distributions compared to the Poisson model. The NBD’s ability to model overdispersion is crucial for precise analysis and interpretation of collision data, as it accounts for the inherent stochasticity in particle production processes.

The Double Negative Binomial (DNB) distribution improves upon the standard Negative Binomial by modeling the charged-particle multiplicity as a mixture of two independent Negative Binomial distributions. This approach accounts for the contribution of distinct event classes – effectively recognizing that particle production isn’t a single, homogeneous process. Each Negative Binomial component within the DNB represents a separate class of events with its own characteristic mean and variance, allowing for a more accurate description of the overall multiplicity distribution when compared to data. The parameters of these component distributions are determined through fitting procedures, and their values reflect the relative contribution and characteristics of each event class to the observed multiplicity.

Validation of nuclear models and collision dynamics relies on comparing simulated charged-particle multiplicity distributions to experimental data. This study demonstrates a significant influence of the geometric description of the oxygen nucleus on these distributions; specifically, models treating oxygen as either alpha-cluster configurations or employing a Woods-Saxon density distribution yield demonstrably different multiplicity predictions. Quantitative comparison of these simulated distributions with experimental measurements from heavy-ion collisions allows for refinement of the nuclear model parameters and provides insight into the initial state of the colliding nuclei. Discrepancies between simulation and experiment indicate areas where the nuclear model requires improvement, such as refinements to the nuclear density distribution or the inclusion of additional physical processes.

Universality and Limits: Implications for Fundamental Theory

The Kolmogorov-Niseneboim-Ostrovsky (KNO) scaling principle proposes a surprising regularity in the chaos of high-energy particle collisions: the distribution of produced particles-its ‘multiplicity’-should exhibit a universal form, irrespective of the colliding particles or the collision’s energy. This suggests an underlying self-similarity in the process of particle production, a phenomenon where the statistical properties remain consistent even as the scale changes. Specifically, KNO scaling predicts that when examining the probability of observing a certain number of particles, this probability distribution-after appropriate normalization-should remain constant across a wide range of energies. Validating this principle isn’t merely about confirming a mathematical prediction; it hints at fundamental symmetries within the strong force, the interaction governing quarks and gluons, and provides crucial constraints on theoretical models describing these interactions, ultimately deepening understanding of matter at its most fundamental level.

Investigations into the production of particles at increasingly high energies reveal underlying patterns in their behavior, and recent work has rigorously tested the principle of KNO scaling to probe the fundamental structure of this process. This principle predicts that the distribution of the number of particles created in high-energy collisions should exhibit a universal form, independent of the specific colliding particles or the collision system. Through detailed simulations and experimental analysis, researchers have now confirmed that KNO scaling holds true across a range of energies and collision types. This finding suggests a remarkable universality in particle production, indicating that the underlying dynamics are governed by a relatively simple set of rules, and provides valuable constraints for theoretical models attempting to describe the strong force and the behavior of matter under extreme conditions.

The emergence of a Saturation Scale represents a pivotal point in high-energy particle collisions, fundamentally altering the dynamics of particle production. As collision energy increases, the density of partons within colliding hadrons grows, eventually leading to a state where their wave functions overlap significantly. This overlap induces saturation effects, effectively limiting further growth in particle multiplicity and establishing a characteristic energy scale – the Saturation Scale. This scale isn’t merely a kinematic threshold; it governs the transition from dilute to dense multiparton interactions, influencing the shape of the multiplicity distribution and impacting the underlying mechanisms responsible for hadronization. Consequently, precise determination of the Saturation Scale provides critical insights into the strong force and the behavior of matter under extreme conditions, revealing how the fundamental constituents of matter interact when pushed to their limits.

These observations regarding particle production and KNO scaling extend beyond purely mathematical descriptions, offering a deeper glimpse into the nature of the strong force-one of the four fundamental forces governing the universe. By confirming universality in high-energy collisions, the research suggests that the underlying dynamics of particle creation are remarkably consistent regardless of the specific conditions. This understanding is crucial for extrapolating the behavior of matter under extreme conditions, such as those found in neutron stars or during the very early stages of the universe following the Big Bang. Investigating these phenomena requires accurate models of the strong force, and validating the principles of universality demonstrated in this study provides a critical benchmark for these theoretical frameworks, ultimately refining QCD and related models.

The study meticulously examines charged particle production in proton-oxygen collisions, acknowledging the inherent complexities of modeling nuclear interactions. It is within this pursuit of accuracy that a resonance can be found with Simone de Beauvoir’s observation: “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.” Similarly, particle multiplicity doesn’t simply exist; it becomes manifest through the interplay of collision dynamics and nuclear structure, influenced by factors like the alpha-cluster versus Woods-Saxon models. The validation of scaling laws, such as KNO scaling via double Negative Binomial Distributions, isn’t a declaration of absolute truth, but rather a repeated attempt to disprove alternative explanations, refining the understanding of these high-energy events. The sensitivity to outliers, in both theoretical predictions and experimental data, remains a critical consideration.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The persistence of KNO scaling, even when probed with oxygen nuclei and modeled via Pythia or kTk-factorization, is less a triumph of theoretical elegance and more a persistent annoyance. It works, which immediately invites suspicion. Any model that so readily accommodates disparate collision systems deserves rigorous testing – specifically, attempts to break it. The choice between alpha-cluster and Woods-Saxon descriptions of oxygen’s nuclear structure remains, predictably, ambiguous. Further refinement of these models isn’t the goal; instead, the focus should be on identifying collision parameters – energy, centrality, even projectile/target combinations – that demonstrably deviate from established scaling laws.

A troubling, and largely unaddressed, aspect of this work, and the field more broadly, is the reliance on phenomenological distributions like the Negative Binomial. While mathematically convenient, such descriptions lack predictive power. They describe multiplicity; they do not explain it. The challenge isn’t to improve the fit of the distribution, but to derive it from first principles – from the underlying dynamics of strong interactions. If the result is too elegant, it’s probably wrong.

Ultimately, the value of these investigations lies not in confirming existing paradigms, but in identifying their limits. The continued pursuit of increasingly complex models, without a corresponding effort to falsify them, is a path to stagnation. The true test of any theory isn’t how well it explains the known, but how gracefully it accommodates the unexpected.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.11452.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- TRX PREDICTION. TRX cryptocurrency

- Xbox Game Pass September Wave 1 Revealed

- EUR USD PREDICTION

- Best Finishers In WWE 2K25

- Top 8 UFC 5 Perks Every Fighter Should Use

- Battlefield 6 Open Beta Anti-Cheat Has Weird Issue on PC

- How to Unlock & Upgrade Hobbies in Heartopia

- Enshrouded: Giant Critter Scales Location

- How to Increase Corrosion Resistance in StarRupture

- All Shrine Climb Locations in Ghost of Yotei

2026-02-15 23:10