Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new theoretical model details how the interplay of confinement and chiral symmetry breaking shapes phase transitions within a hidden sector governed by dark QCD.

This work investigates Z(3) metastable bubble nucleation and its coupling with chiral order parameters across a finite-temperature dark-QCD deconfinement transition.

Understanding the interplay between confinement and chiral symmetry breaking remains a central challenge in non-perturbative quantum chromodynamics. This is addressed in ‘Z(3) Metastable Bubbles and Chiral Dynamics Across a Dark-QCD Deconfinement Transition’, which develops a theoretical framework to explore these dynamics within a dark QCD sector exhibiting an explicit Z(3) structure. The analysis reveals how the coupling between the Z(3) Polyakov loop and chiral order parameters governs the formation of domain walls and the nucleation of metastable bubbles, providing a pathway from vacuum structure to finite-temperature behavior. Could this framework offer new insights into the cosmological implications of dark sector phase transitions and their potential observational signatures?

The Allure of Impermanence: Navigating Metastable States

Numerous physical systems don’t simply settle into a single, lowest-energy state; instead, they frequently inhabit metastable states – temporary conditions of relative stability perched atop energy barriers. Imagine a ball resting in a shallow dip on a hillside; it’s stable for a time, but a sufficient disturbance could push it over the crest, allowing it to roll downhill to a state of true equilibrium. This phenomenon isn’t limited to classical mechanics; it’s pervasive in fields like materials science, where supercooled liquids retain a disordered structure despite being thermodynamically unstable, and in particle physics, where the universe’s vacuum itself might not be in its absolute lowest energy configuration. The height of these energy barriers, and the probability of overcoming them via quantum tunneling or thermal fluctuations, determine the lifetime of these metastable states, shaping the behavior of the system over time and influencing its ultimate fate.

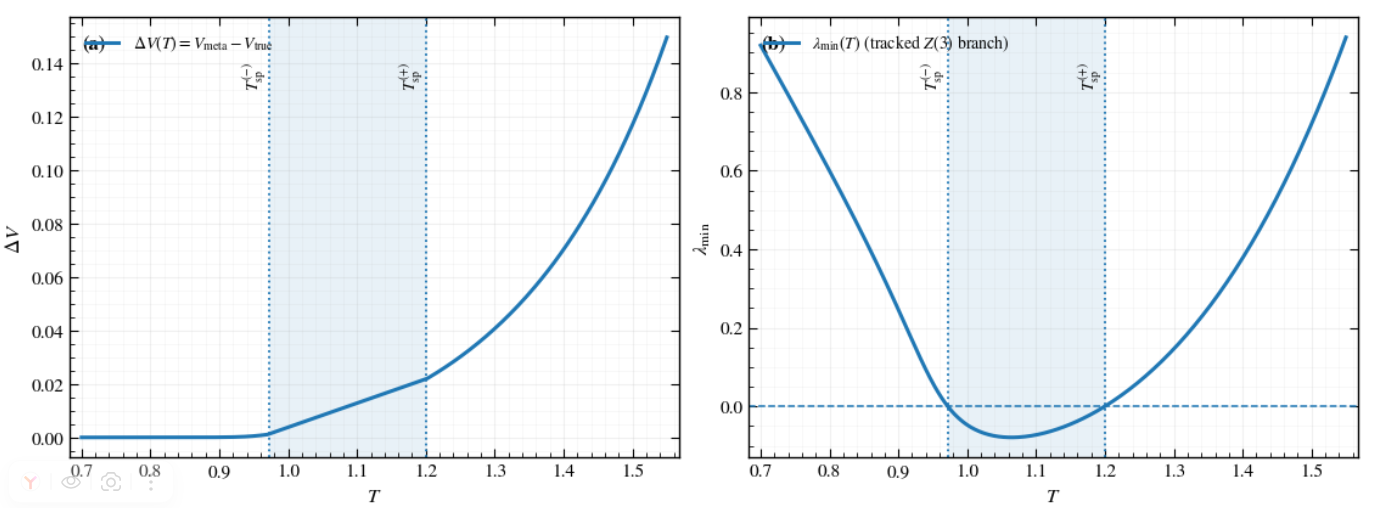

Predicting when a system will shift from a metastable state to a truly stable one hinges on precisely defining the ‘Metastability Window’ – the range of conditions where a false vacuum persists. This window isn’t simply a fixed boundary; it’s a dynamic region shaped by factors like temperature, pressure, and quantum tunneling effects. Within this window, a system appears stable, but it remains vulnerable to decay via the formation of bubbles of true vacuum. Calculations focused on identifying the limits of this window are therefore vital, as they determine the lifespan of the metastable state and the likelihood of a phase transition. A narrowing window signals an increased risk of decay, potentially triggering a dramatic shift in the system’s fundamental properties, while a wider window suggests greater longevity and resilience. The ability to accurately map this landscape is thus central to understanding phenomena ranging from the decay of exotic particles to the ultimate fate of the universe.

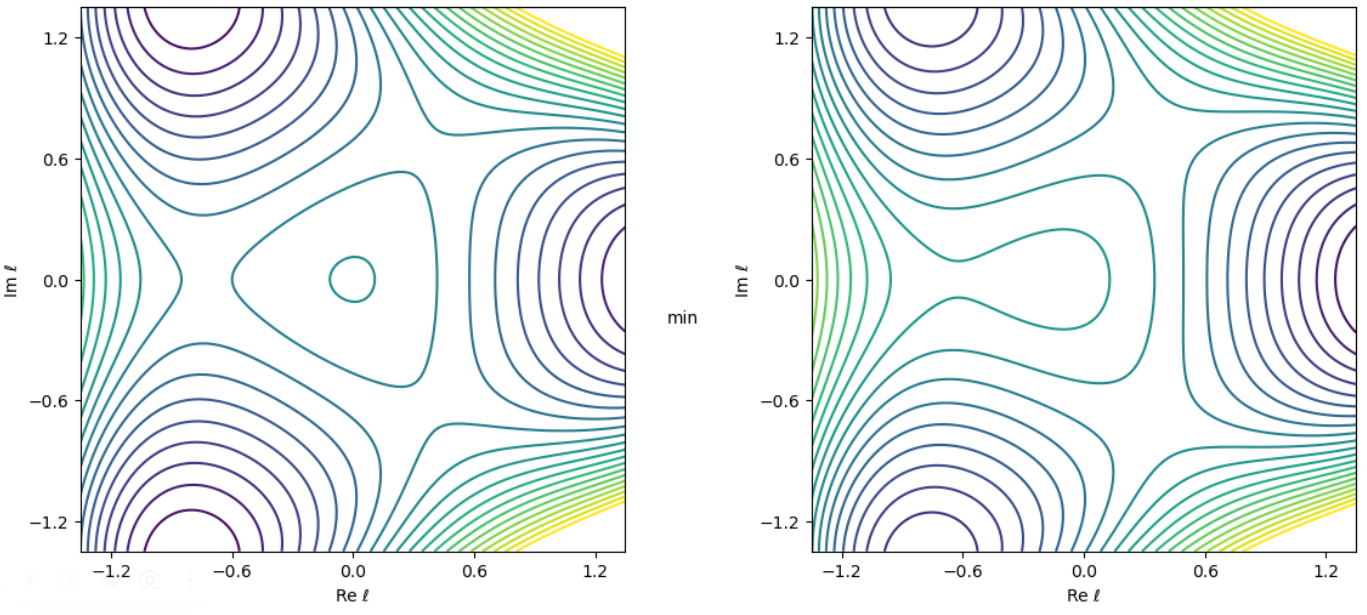

The stability of any given physical state hinges on its free energy – a thermodynamic potential that balances internal energy with the tendency to minimize that energy through configuration. Essentially, a system will naturally gravitate towards states with the lowest possible free energy. Identifying the minima of this free energy landscape is therefore paramount; these minima represent the most stable configurations the system can adopt. However, the landscape isn’t always simple. It can feature numerous local minima – metastable states separated from the true, global minimum by energy barriers. F = U - TS, where F is free energy, U is internal energy, T is temperature, and S is entropy, illustrates this relationship. Determining these minima isn’t merely an academic exercise; it allows prediction of phase transitions and the likelihood of a system tunneling through an energy barrier to reach a lower, more stable state – a crucial consideration in fields ranging from cosmology to materials science.

Modeling Transitions: The Effective Landau-Ginzburg Approach

The Effective Landau-Ginzburg theory is a field-theoretic approach used to model phase transitions, particularly in condensed matter and high-energy physics. It posits that the free energy of a system near a critical point can be expressed as a functional expansion in terms of an order parameter and its gradients. This allows for the description of both first and second-order phase transitions, and importantly, captures the collective behavior arising from the interactions between numerous degrees of freedom. Unlike microscopic models, the Landau-Ginzburg theory focuses on the macroscopic properties near the transition, effectively integrating out the short-wavelength fluctuations and providing a simplified, yet accurate, description of the system’s dynamics. The power of this approach lies in its ability to predict critical exponents and the overall behavior of the system without requiring detailed knowledge of the underlying microscopic interactions.

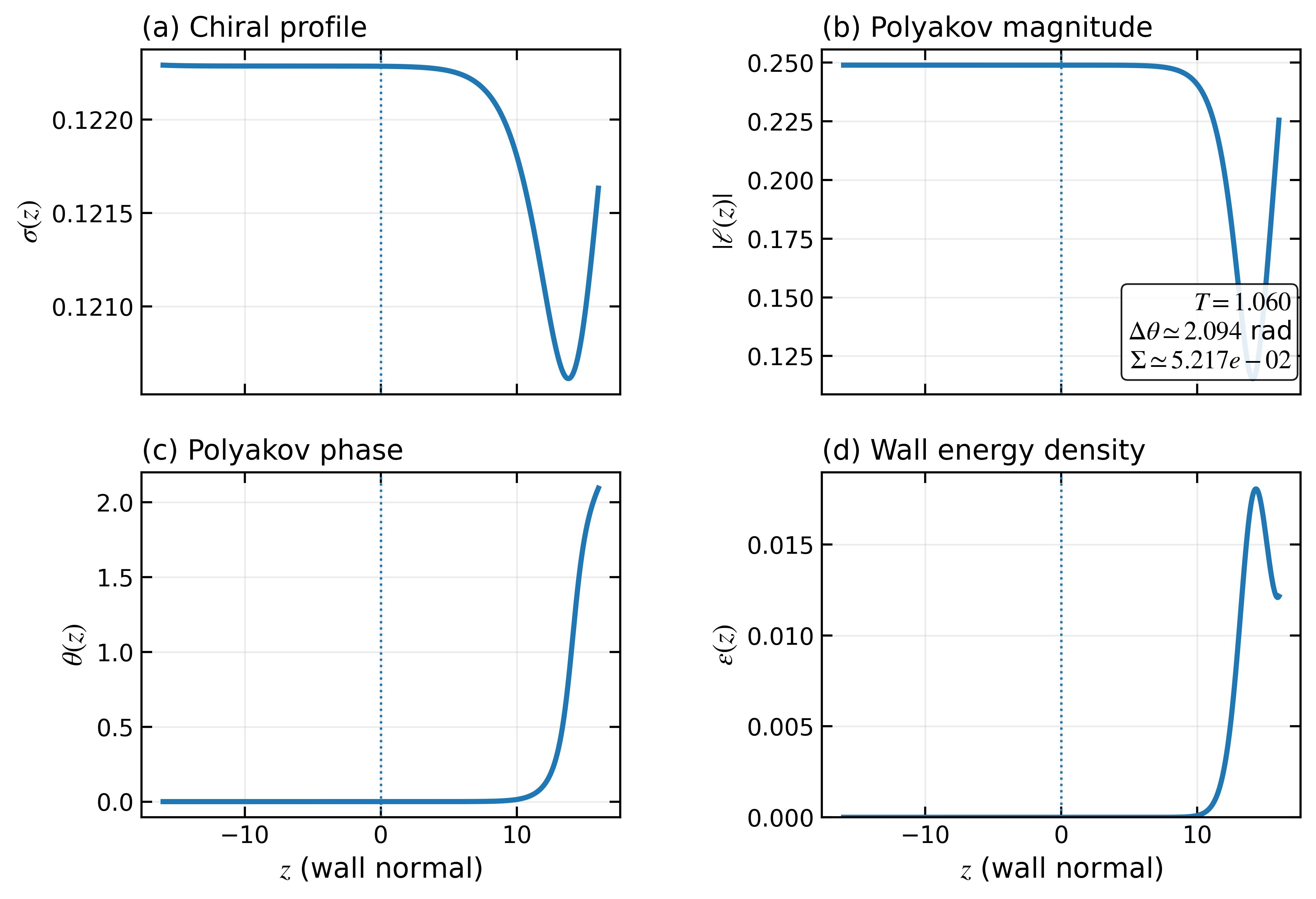

The Effective Landau-Ginzburg theory employs the chiral condensate, \langle \bar{\psi} \psi \rangle, and the Polyakov loop, \mathcal{P} = \text{Tr}[T \exp(i \in t_0^\beta d\tau A_4(\tau))] , as primary order parameters to characterize the dynamics of phase transitions. The chiral condensate quantifies the spontaneous breaking of chiral symmetry and the formation of quark-antiquark pairs, while the Polyakov loop serves as an indicator of confinement/deconfinement transition in gauge theories. These parameters are not merely static values; their fluctuations and interplay define the system’s behavior near critical points, providing a means to model the complex interplay between different degrees of freedom and predict the resulting phase structure.

The Z(3) symmetry, a discrete symmetry, fundamentally constrains the behavior of the Polyakov loop, which serves as an order parameter for quark confinement. This symmetry dictates that the Polyakov loop transforms under Z(3) transformations, resulting in three degenerate minima in the effective potential. Consequently, the system exhibits three distinct symmetry-breaking patterns, each corresponding to a different vacuum state. The presence of this symmetry, and its potential breaking, directly impacts the confinement/deconfinement phase transition and the overall symmetry structure of the strongly coupled system, influencing the properties of hadrons and the quark-gluon plasma.

The backreaction effect describes the mutual influence between the chiral condensate, \langle \bar{\psi} \psi \rangle, and the Polyakov loop, \langle W \rangle, on the effective potential governing the phase transition. This interaction isn’t simply a static coupling; the expectation value of the chiral condensate directly modifies the potential experienced by the Polyakov loop, and vice versa. Specifically, fluctuations in the chiral condensate contribute to the potential terms influencing the Polyakov loop’s behavior, altering its minima and thus the transition temperature. Conversely, the Polyakov loop’s expectation value modifies the potential felt by the chiral condensate, impacting its own condensation. This bi-directional modification introduces non-trivial dynamics and alters the symmetry breaking pattern compared to scenarios where these order parameters are treated independently, leading to a richer phase diagram and potentially new phases of matter.

From Instability to New Phases: The Birth of Bubbles

Bubble nucleation is a common mechanism for first-order phase transitions, observed in systems undergoing liquid-gas, liquid-solid, or even magnetic transformations. This process involves the spontaneous formation of a new, thermodynamically favored phase as discrete, spatially localized bubbles within the pre-existing phase. These bubbles initially form as fluctuations, and their growth is dependent on overcoming an energy barrier. The appearance of bubbles indicates that the system is transitioning from a metastable or unstable state to a lower-energy phase. This nucleation pathway avoids the need for a simultaneous, system-wide transition and allows the new phase to expand gradually, ultimately consuming the original phase.

Bubble nucleation is thermodynamically driven by the system’s tendency to minimize its free energy. The formation of a new phase within the old is energetically favorable due to the reduction in volume free energy \Delta F_v associated with the phase transition. However, creating an interface between the new and old phases incurs an energetic cost proportional to the surface tension γ and the surface area A of the bubble. Consequently, bubble formation requires overcoming an energy barrier where the decrease in free energy from volume changes must exceed the increase in free energy due to surface tension; this balance dictates whether a stable nucleus will form and grow, or dissolve back into the parent phase.

The nucleation barrier represents the minimum energy input required to overcome the energetic penalty associated with forming the initial seed of a new phase. This barrier arises from the surface tension at the interface between the new and old phases; creating any initial volume of the new phase necessitates generating this interface, which costs energy proportional to its area. Only fluctuations exceeding the height of this barrier – statistically less probable events – will result in a stable nucleus capable of sustained growth. The magnitude of the nucleation barrier is influenced by both the thermodynamic properties of the materials involved and the environmental conditions, such as temperature and pressure, and can be quantified using models based on classical nucleation theory, often expressed as \Delta G^* = \frac{16\pi \gamma^3}{3\Delta G_v^2} , where γ is the interfacial tension and \Delta G_v is the volume free energy change.

The metastability window defines the range of thermodynamic conditions – specifically, temperature and pressure – where a new phase can nucleate but is not yet fully stable. Within this window, the system exists in a locally stable, yet not globally minimal, energy state. Nucleation is favored when the system is sufficiently far from equilibrium, exceeding the nucleation barrier, but before reaching a point where the new phase becomes thermodynamically preferred and grows rapidly without an energy barrier. The size of the metastability window is determined by the free energy difference between the initial and final phases and is inversely proportional to the magnitude of the surface tension; a larger free energy difference or lower surface tension broadens the window, increasing the likelihood of nucleation at a given condition.

Quantifying the Transition: Critical Radius and the Euclidean Path

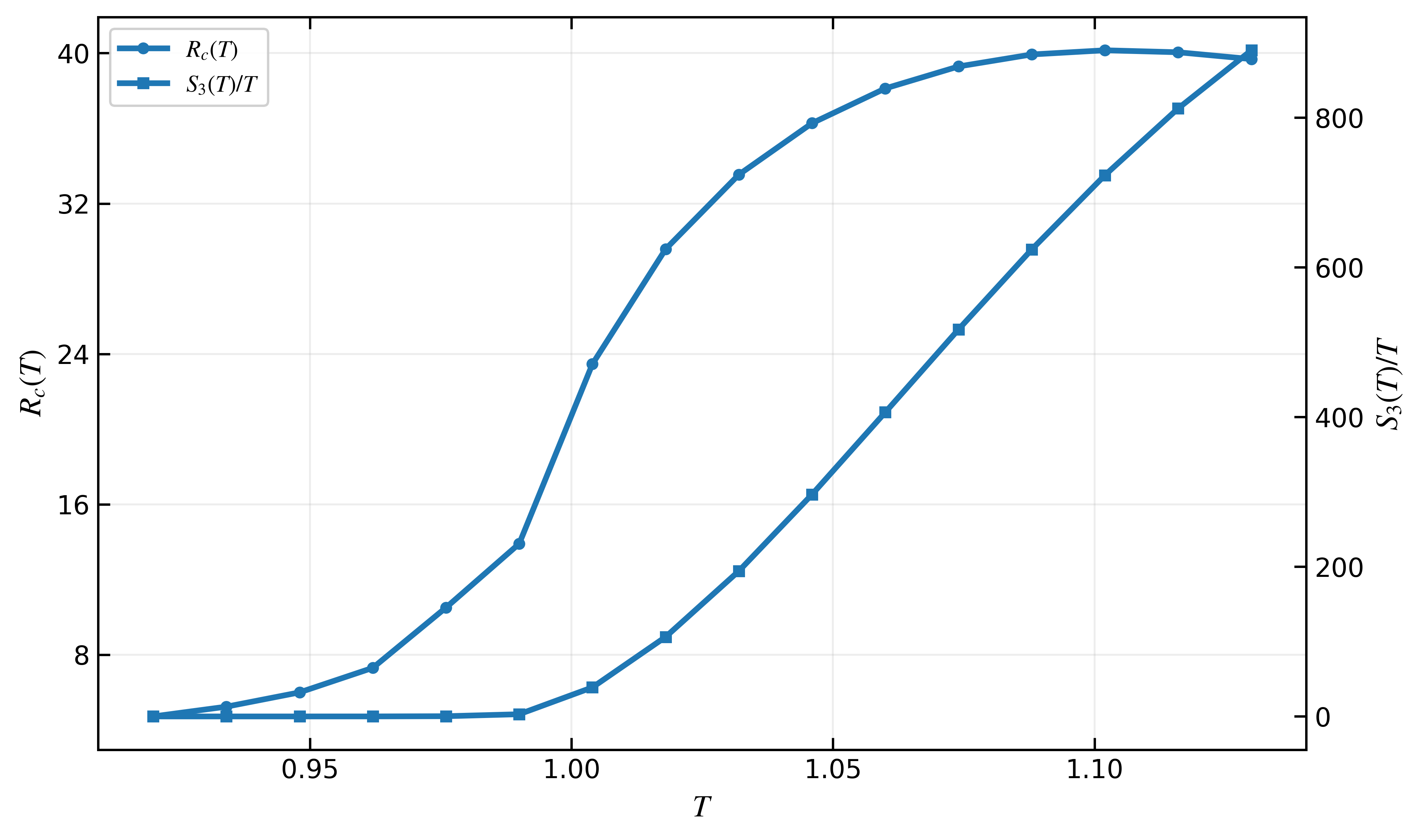

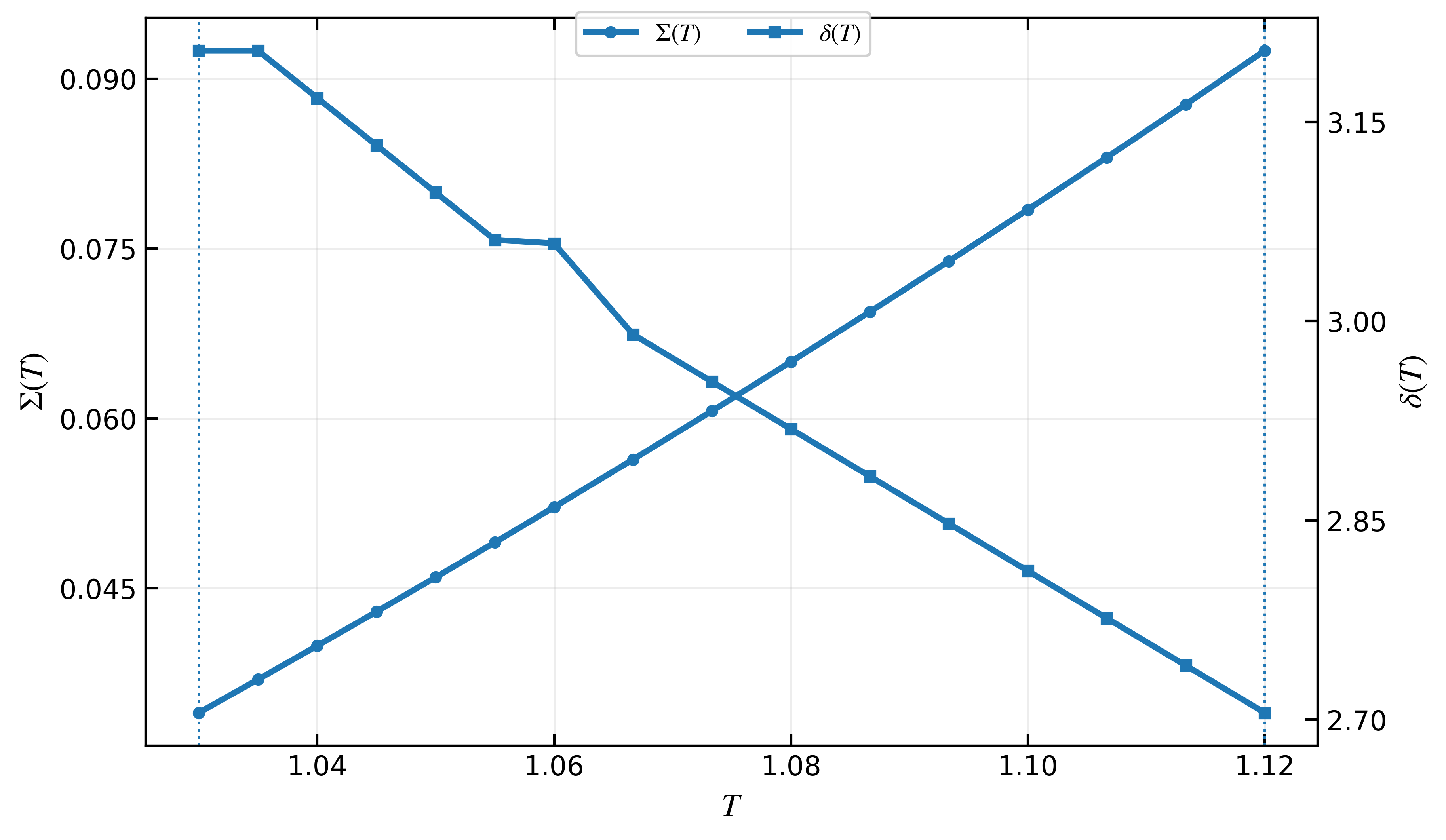

The stability of a newly forming phase within another hinges on achieving a critical size, encapsulated by the ‘Critical Radius’ – a fundamental parameter in understanding phase transitions. Defined as R_c(T) = 2\Sigma(T)/\Delta V(T), this radius represents the minimum bubble size necessary for continued growth, as opposed to shrinking and disappearing. Crucially, this value isn’t arbitrary; it’s directly proportional to the surface tension \Sigma(T) and inversely proportional to the volume difference \Delta V(T). A higher surface tension requires a larger radius to overcome the energetic cost of creating an interface, while a larger volume difference – a greater density contrast – facilitates growth at smaller radii. Therefore, the Critical Radius provides a quantifiable threshold; bubbles smaller than this value are energetically unfavorable and will collapse, while those exceeding it are poised for stable expansion, driving the overall phase transformation.

The spinodal criterion marks a critical turning point in phase transitions, identifying the precise conditions where a system shifts from a state of stable, though improbable, bubble formation to one of spontaneous decay. This criterion is mathematically defined by the vanishing of the smallest eigenvalue of the Hessian matrix, a measure of the system’s curvature in its free energy landscape. Below the spinodal temperature, even minute fluctuations can trigger growth, as the system becomes inherently unstable against perturbations; nucleation is no longer required. Consequently, the transition mechanism changes dramatically – from one governed by e^{-S_3/T} – where S_3 represents the nucleation action and exponential suppression dominates – to one driven by the unrestricted growth of existing fluctuations, bypassing the energy barrier associated with initial bubble formation. This shift signifies a fundamental change in the kinetics of the transition, impacting the rate and morphology of the emerging phase.

The Euclidean bounce calculation offers a rigorous method for determining the prefactor within the rate equation governing bubble nucleation, thereby providing a complete quantification of the phase transition. This technique involves solving a third-order differential equation – a ‘bounce’ – in Euclidean space, effectively modeling the path of a bubble from an infinitely small size to a critical radius where it becomes stable. The resulting solution yields the prefactor, which accounts for factors beyond the exponential suppression of the nucleation rate, such as the bubble’s surface area and the energy cost associated with its formation. By accurately calculating this prefactor, researchers gain a more precise understanding of how quickly a new phase will emerge from a metastable state, offering valuable insights into diverse phenomena ranging from cosmological phase transitions to the formation of precipitates in materials science. The calculation’s success relies on finding the trajectory that minimizes the action, S_3, allowing for a determination of the probability of bubble formation at a given temperature.

The rate at which a new phase emerges within a system isn’t simply a matter of reaching a critical temperature; it’s governed by an exponential suppression factor, precisely quantified by the ‘Nucleation Action’. This action, expressed as S_3(T)/T \approx (16\pi/3)\Sigma(T)^3/(T\Delta V(T)^2), reveals how strongly surface tension, \Sigma(T), and the change in volume, \Delta V(T), resist the formation of a new, stable phase. A larger nucleation action signifies a greater energy barrier, drastically reducing the probability of bubble formation and slowing the transition process; conversely, a smaller action facilitates rapid phase change. This calculation isn’t merely theoretical, offering a pathway to predict the longevity of metastable states and providing crucial insight into phenomena ranging from the boiling of liquids to the formation of new universes in the early cosmos.

Precise calculations of critical radii, nucleation actions, and the spinodal criterion offer a significantly refined understanding of how phase transitions occur and subsequently influence the long-term stability of physical systems. These aren’t merely theoretical exercises; they provide quantitative predictions for transition rates, allowing researchers to model and anticipate behavior in diverse scenarios – from the formation of bubbles in boiling liquids to the decay of metastable materials. The ability to determine, for example, the prefactor in bubble nucleation rates via a S_3(T)/T calculation, or to pinpoint instability through the spinodal criterion, moves beyond qualitative descriptions toward a predictive capability crucial for materials science, cosmology, and beyond. By establishing a firm mathematical framework, these calculations offer insights into the delicate balance between surface tension, volume changes, and thermal fluctuations that govern the evolution of these systems over time.

Beyond Uniformity: The Landscape of Domain Walls

The theoretical framework, initially focused on uniform vacuum states, possesses the capacity to describe more complex, non-uniform configurations through the introduction of ‘domain walls’. These walls aren’t simply boundaries, but rather interfaces separating distinct regions where the vacuum expectation value – the lowest energy state of a field – differs. Imagine a landscape with multiple valleys; a domain wall represents the boundary between these valleys, each representing a different stable vacuum. Mathematically, these walls arise as solutions to the Effective Landau-Ginzburg Theory, allowing for the prediction of their properties like tension and stability. This extension is crucial because many physical systems, from condensed matter physics to cosmology, exhibit such non-uniformity, and understanding these domain walls provides insights into the system’s overall behavior and potential phase transitions.

The existence of domain walls, boundaries separating distinct vacuum states, isn’t merely a theoretical prediction but a demonstrable consequence of the Effective Landau-Ginzburg Theory. This theory, a cornerstone of condensed matter physics and increasingly relevant to cosmology, provides the mathematical framework for understanding how these walls emerge as stable, albeit localized, solutions to the equations governing the system’s energy. Specifically, the solutions reveal that domain walls arise when the system minimizes its energy by transitioning between different vacuum expectations, creating an interfacial region where the order parameter varies continuously. This connection is crucial because it allows physicists to predict the properties of domain walls – such as their tension and stability – directly from the parameters of the Landau-Ginzburg free energy functional, offering a powerful tool for analyzing systems exhibiting complex, non-uniform configurations and potentially unlocking insights into phenomena ranging from superconductivity to the early universe.

The investigation of complex configurations, particularly those involving domain walls, offers a powerful lens through which to examine systems exhibiting intricate internal structures. These aren’t merely abstract mathematical curiosities; they represent genuine possibilities for how energy can be distributed within a field, leading to potentially stable, yet non-uniform, states. By meticulously mapping these configurations, researchers gain insights into the collective behavior of constituent parts and the emergence of macroscopic properties. Such analysis transcends simple, homogeneous models, enabling a deeper understanding of phenomena ranging from the behavior of materials with complex magnetic ordering to the formation of topological defects in the early universe. The ability to characterize these internal landscapes promises a more nuanced and accurate portrayal of systems far removed from idealized uniformity, potentially unlocking new avenues for both theoretical advancement and practical application.

The established framework, demonstrating the behavior of complex systems through domain walls and non-uniform configurations, presents a compelling pathway for investigation across diverse scientific fields. Researchers anticipate applying these principles to model phenomena ranging from the intricacies of condensed matter physics – such as the behavior of exotic materials and phase transitions – to the large-scale structure of the universe itself. Cosmological applications include exploring the formation of topological defects during phase transitions in the early universe and potentially providing new insights into dark matter and dark energy. Furthermore, this adaptable framework holds promise for advancements in materials science, potentially enabling the design of novel materials with tailored properties by controlling domain wall configurations at the nanoscale. The versatility of this approach suggests a broad impact, extending beyond theoretical exploration into tangible advancements in various scientific disciplines.

The study of dark QCD and its deconfinement transition reveals a fascinating interplay between symmetry breaking and the emergence of topological structures. It observes how Z(3) metastability influences bubble nucleation, subtly shaping the landscape of chiral dynamics. As Pyotr Kapitsa once noted, “It is in the process of decay that one finds the most beautiful forms.” This sentiment resonates deeply with the findings; the transition isn’t simply about breaking symmetry, but about how that breaking manifests-the graceful evolution of confinement-related structures and the formation of domain walls. The researchers don’t attempt to accelerate the process, but rather carefully map its features, recognizing that observing the intricacies of decay provides the most profound insights into the underlying physics.

What Lies Ahead?

The presented framework, while detailing a coupling between confinement and chiral transitions within a dark QCD sector, inevitably highlights the provisional nature of such constructions. Every abstraction carries the weight of the past; the imposed Z(3) symmetry, for instance, represents a choice-a simplification-that may obscure more fundamental dynamics. Future work must confront the limitations inherent in discretizing continuous symmetries, exploring the effects of subleading operators and potential symmetry restoration at higher energies. The resilience of the model hinges on its capacity to accommodate deviations from idealized conditions.

A pressing challenge lies in extending these theoretical insights to genuinely dynamical scenarios. Static bubble nucleation barriers, however well-defined, are merely snapshots of a complex evolution. Understanding the time-dependent interplay between domain wall formation, bubble collapse, and the generation of potentially observable signatures requires tackling the non-equilibrium dynamics of these systems – a notoriously difficult undertaking. The slow burn of gradual change, rather than abrupt phase transitions, may prove the more persistent feature of a dark sector.

Ultimately, the value of this work rests not in definitive answers, but in the questions it provokes. The model provides a lens through which to view the intricate dance between confinement and chiral symmetry breaking. However, any attempt to map this theoretical landscape onto reality must acknowledge that all systems decay-the question is whether they age gracefully, or succumb to unforeseen instabilities. Only slow change preserves resilience.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.15342.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Xbox Game Pass September Wave 1 Revealed

- TRX PREDICTION. TRX cryptocurrency

- EUR USD PREDICTION

- Best Finishers In WWE 2K25

- Top 8 UFC 5 Perks Every Fighter Should Use

- How to Increase Corrosion Resistance in StarRupture

- Enshrouded: Giant Critter Scales Location

- How to Unlock & Upgrade Hobbies in Heartopia

- Battlefield 6 Open Beta Anti-Cheat Has Weird Issue on PC

- Sony Shuts Down PlayStation Stars Loyalty Program

2026-01-24 07:29