Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have developed a novel coding approach to classify and understand the complex stationary states of Bose-Einstein condensates trapped in one-dimensional quasiperiodic lattices.

A symbolic dynamics method provides a framework for analyzing the solutions of the Gross-Pitaevskii equation in quasiperiodic potentials, revealing connections to Anderson localization.

Understanding the behavior of quantum systems in disordered environments remains a significant challenge, particularly when traditional analytical methods fail. This is addressed in ‘Towards the complete description of stationary states of a Bose-Einstein condensate in a one-dimensional quasiperiodic lattice: A coding approach’, which proposes a novel framework for characterizing stationary states within such systems. The authors demonstrate a one-to-one correspondence between these states and bi-infinite sequences, effectively establishing a “coding” approach for their classification and analysis. Could this method provide a pathway towards a more complete understanding of Anderson localization and other complex phenomena in quasiperiodic potentials?

The Perilous Dance with Aperiodicity

The Gross-Pitaevskii Equation, a cornerstone for describing the behavior of Bose-Einstein condensates and other quantum systems, encounters significant hurdles when applied to quasiperiodic potentials. Unlike the relative simplicity of purely periodic landscapes, quasiperiodic arrangements – characterized by order without strict repetition – introduce a level of complexity that overwhelms conventional numerical and analytical techniques. Standard methods, designed for predictable, repeating patterns, struggle to accurately resolve the intricate interplay between order and disorder inherent in these systems. This difficulty stems from the equation’s sensitivity to small perturbations and the resulting instability in long-term calculations; the solutions can become erratic and diverge rapidly, hindering the ability to predict system behavior. Consequently, researchers are compelled to develop novel computational strategies and theoretical frameworks capable of navigating the unique challenges posed by these aperiodic, yet structured, potentials.

Quasiperiodic potentials represent a fascinating departure from the predictable landscapes of purely periodic systems, introducing a delicate balance between order and disorder that significantly complicates theoretical and computational investigations. While periodic potentials allow for the application of powerful mathematical tools like Bloch’s theorem, quasiperiodic arrangements – characterized by a lack of strict translational symmetry – invalidate these approaches. This absence of symmetry doesn’t result in complete randomness, however, but rather a complex interference pattern that creates a unique spectral fingerprint. Consequently, analytical solutions to the Schrödinger equation become exceedingly difficult to obtain, and numerical methods often struggle with instability due to the intricate interplay between constructive and destructive interference. The resulting wavefunctions exhibit behaviors distinct from both perfectly ordered and entirely chaotic systems, demanding specialized techniques to accurately model and predict their properties.

The investigation of solutions within quasiperiodic systems provides a critical framework for understanding Anderson Localization, a phenomenon where wave functions-describing the probability of finding a particle-become increasingly confined to specific regions of space. Unlike materials with perfect periodicity where waves propagate freely, quasiperiodic potentials introduce a delicate balance between order and disorder, leading to interference effects that dramatically alter wave behavior. This confinement isn’t due to external boundaries, but rather an intrinsic property of the disordered potential itself; the particle effectively creates its own localized ‘trap’. Modeling this localization accurately requires a deep understanding of how solutions to the governing equations, such as the Gross-Pitaevskii equation, respond to these complex, aperiodic landscapes, offering insights into diverse physical systems ranging from cold atoms in optical lattices to the electronic properties of disordered materials.

Decoding the Chaos: A Symbolic Approach

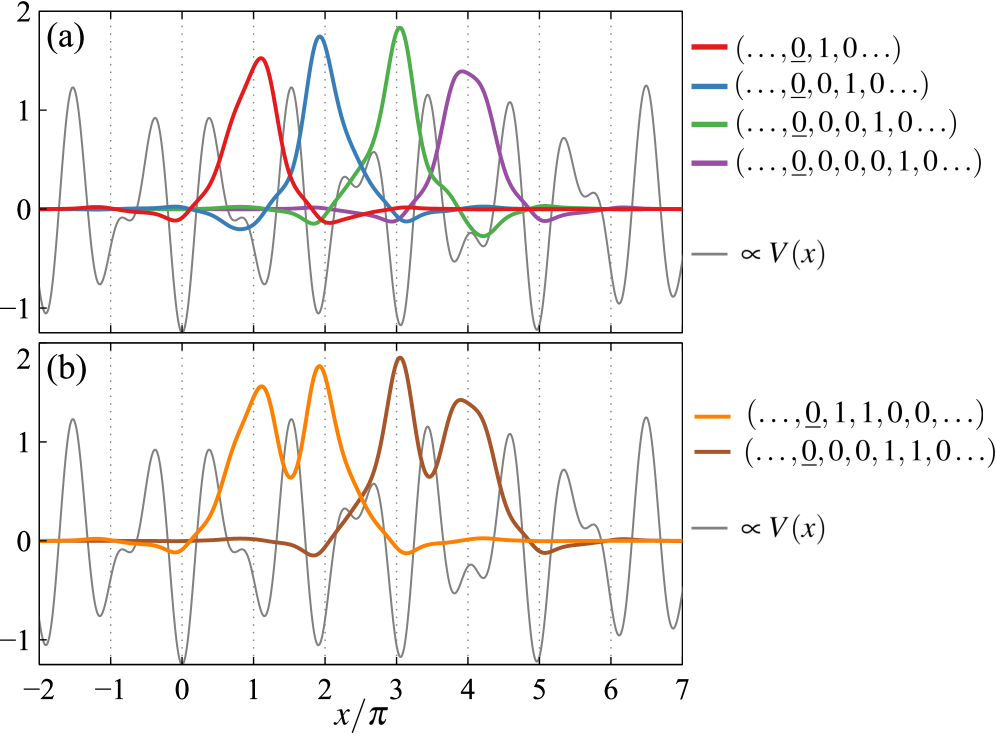

The Coding Approach leverages Symbolic Dynamics to categorize solutions by representing them as bi-infinite sequences. This involves defining a finite set of symbols that correspond to qualitative features of the solution’s behavior, such as its sign or rate of change within defined intervals. By tracking the sequence of these symbols as the independent variable evolves, each solution is uniquely encoded. This transformation allows for the analysis of continuous solution spaces through the discrete properties of their corresponding sequences, providing a systematic method for classification and differentiation.

The classification of solutions as either ‘Regular’ or ‘Singular’ is achieved through the analysis of their corresponding bi-infinite sequences generated by Symbolic Dynamics. Specifically, sequences representing solutions exhibiting unbounded behavior – those that extend infinitely without limit – are systematically filtered out. This filtering process relies on identifying sequence patterns indicative of divergence or instability within the underlying differential equation or system. By removing these unbounded sequences, the remaining sequences are definitively categorized as representing ‘Regular Solutions,’ which are bounded and well-defined over the relevant domain. This method provides a clear and computationally efficient distinction between solution types based purely on the characteristics of their symbolic representations.

Establishing a bijective mapping between the solution space of a continuous dynamical system and the set of corresponding bi-infinite symbolic sequences allows for the transformation of a continuous classification problem into a discrete one. This conversion facilitates robust classification because discrete sequences are less susceptible to numerical errors and computational limitations inherent in analyzing continuous functions. Specifically, identifying patterns and properties within these sequences-such as periodicity or the presence of specific motifs-becomes a reliable method for categorizing solutions. This approach avoids the challenges associated with directly analyzing potentially unstable or ill-defined continuous behaviors, offering a computationally efficient and numerically stable classification scheme.

Taming the Boundaries: Lipschitz Continuity and Stable Islands

The stability of domains containing ‘Regular Solutions’ is directly contingent upon the Lipschitz continuity of the curves defining their boundaries. Lipschitz continuity, in this context, ensures that the rate of change of the boundary curves is bounded; this is quantified by the Lipschitz constant, denoted as γ. Specifically, for a curve γ, Lipschitz continuity implies that the absolute value of the slope is less than or equal to γ for all points on the curve. A smaller γ value indicates a smoother, more constrained boundary and, consequently, a more stable solution domain. The value of γ therefore serves as a quantifiable metric for assessing the stability of a ‘Regular Solution’ domain, with lower values correlating to increased stability.

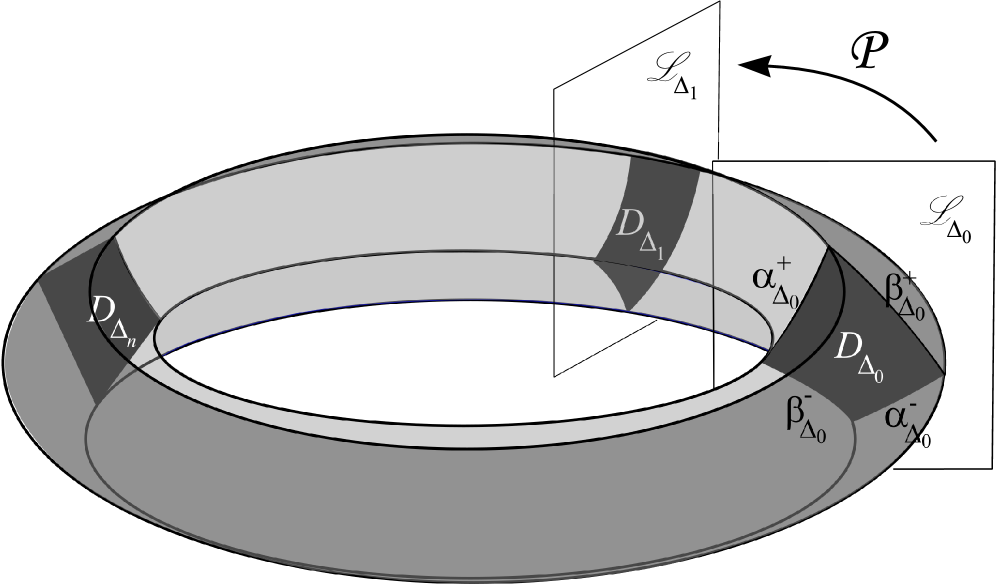

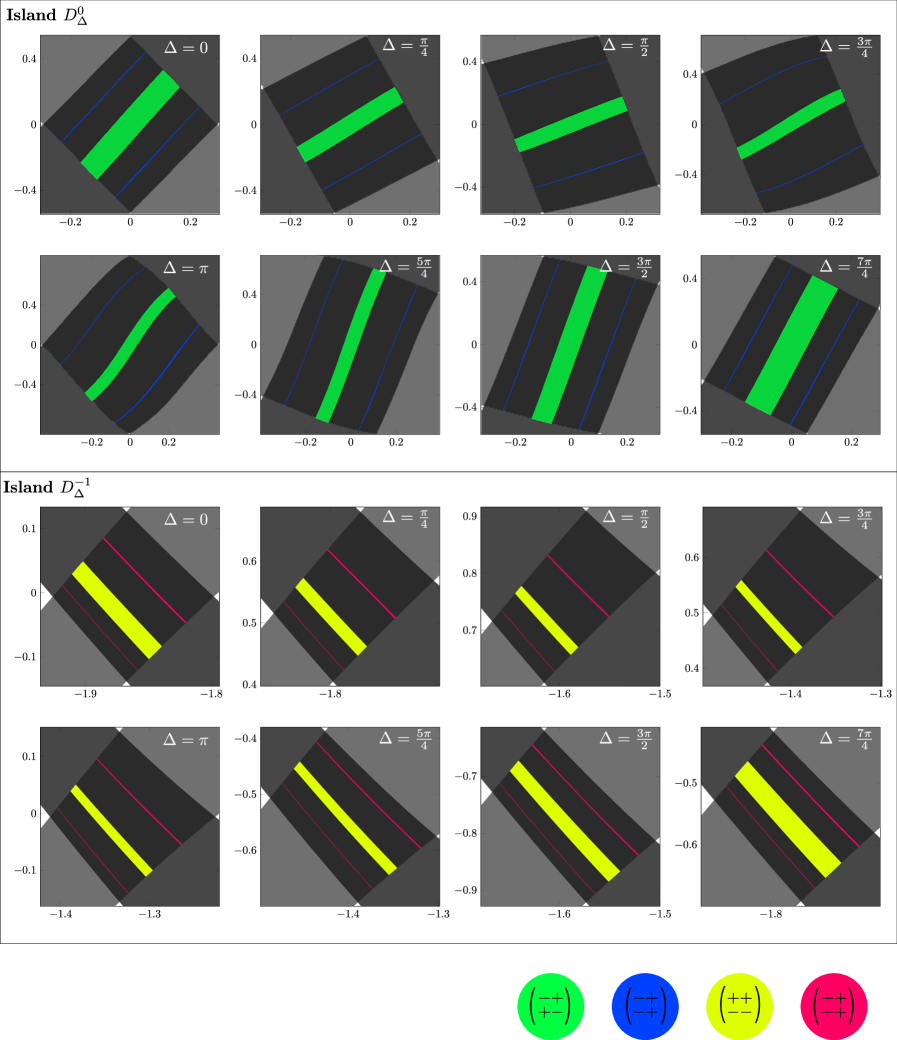

A γ-Island represents a region of stability in solution domains, formally defined by boundaries composed of monotonic γ-Lipschitz curves. These curves adhere to a Lipschitz condition, meaning the rate of change of the function defining the curve is bounded by the constant γ. Monotonicity ensures the curve consistently increases or decreases within the island’s boundary, preventing oscillations or reversals. Mathematically, a curve f is γ-Lipschitz if |f(x) - f(y)| \le \gamma |x - y| for all x and y within the domain. The γ value therefore directly quantifies the smoothness and stability of the island’s boundary, with lower values indicating more stable, less fluctuating boundaries.

A γ-Donut is defined as a continuous deformation of a γ-Island, expanding the concept of stable solution domains beyond strictly bounded regions. This deformation allows for the characterization of solution stability even when boundaries are not closed or exhibit gradual transitions. Mathematically, a γ-Donut maintains the γ-Lipschitz continuity property throughout its deformation, ensuring that the rate of change of the solution within the domain remains bounded. By allowing for continuous variations in shape and size while preserving the γ parameter, γ-Donuts provide a more generalized and comprehensive framework for analyzing the stability of solutions compared to the restrictive definition of γ-Islands.

Validating the Model: Numerical Checks and Spectral Signatures

Numerical verification of solution stability within the identified γ-Islands is achieved through the application of the Poincaré Map and the Linearization Matrix. The Poincaré Map reduces the continuous dynamical system to a discrete map, allowing for iterative tracking of trajectories and identification of stable or unstable fixed points. Simultaneously, the Linearization Matrix, derived from the Jacobian of the system, provides local stability information around these points; its eigenvalues determine whether nearby trajectories converge towards or diverge from the fixed point. Specifically, eigenvalues with magnitudes less than one indicate local stability, confirming the robustness of the solution within the γ-Island. This combined approach enables a computationally efficient method for validating the persistence of these solutions and characterizing their sensitivity to initial conditions.

The verification of stability within identified γ-Islands is streamlined through the application of Strip Mapping Theorems. These theorems establish a relationship between the local dynamics and the width of stable and unstable strips in phase space. Quantification of strip thickness is achieved using the parameters dh(H) and dv(V), representing the half-width of the stable and unstable strips, respectively, as functions of the action variables H and V. By precisely determining these values, the theorems allow for a simplification of the stability analysis, reducing the computational complexity required to confirm the persistence of solutions within the γ-Islands and providing a rigorous, quantifiable metric for assessing stability.

The energy spectrum derived from numerical simulations exhibits characteristics consistent with quasiperiodic systems, specifically a fractal spectrum and the presence of mobility edges. The fractal nature of the spectrum, observed as a non-integer scaling dimension, indicates a complex distribution of states and a departure from the discrete spectra found in periodic systems. Mobility edges – points in the energy spectrum separating localized and extended states – are identified by analyzing the level repulsion statistics and the spatial distribution of wavefunctions. The localization length diverges at these edges, signifying a transition in the nature of electronic states and impacting transport properties within the quasiperiodic lattice. These spectral features confirm the non-trivial topological properties and unique behavior expected of quasiperiodic systems, differing significantly from both periodic and truly disordered materials.

The pursuit of complete descriptions, as this paper outlines for Bose-Einstein condensates in quasiperiodic lattices, feels…predictable. It’s a lovely bit of coding, establishing correspondences between solutions and bi-infinite sequences, but one can’t help but suspect it’s merely a more elaborate way to describe the same fundamental chaos. As Albert Einstein once said, ‘The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results.’ This work, while mathematically sound, feels like a refinement of existing analytical tools, a prettier wrapper around the inherent unpredictability of complex systems. It’s a new lens, certainly, but the underlying mess remains. Everything new is just the old thing with worse docs.

Beyond the Symbolic Dance

The correspondence established between solutions of the Gross-Pitaevskii equation in quasiperiodic lattices and these bi-infinite sequences is, predictably, neat. It allows for classification, a comfortingly familiar activity in any field. However, the practical implications of knowing which sequence corresponds to which stationary state remain to be seen. The truly interesting behavior-dynamics, instability, the inevitable breakdown of these ‘stationary’ states under any realistic perturbation-is, as always, left for another paper. One suspects that the elegance of the coding approach will be most useful when confronting the messiness of real-world systems.

The claim of insight into Anderson localization, while intriguing, feels…familiar. Every few years, a new framework promises to ‘finally’ explain localization, only for production to reveal edge cases and unforeseen interactions. The authors rightly focus on one dimension; scaling this to higher dimensions, where analytical solutions become exponentially harder to obtain, will likely expose limitations. The real challenge won’t be finding sequences that fit the theory, but explaining why the system consistently chooses the ones it does-or, more likely, why it doesn’t.

Future work will undoubtedly involve exploring different lattice potentials and interaction strengths. The search for ‘universal’ sequences, those that appear across a wide range of parameters, is a natural next step. It would be more surprising, however, if these sequences didn’t eventually succumb to the same fate as all elegant models: becoming a specialized tool, useful within a narrow regime, but ultimately insufficient to capture the full complexity of the physical world.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.17172.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Poppy Playtime Chapter 5: Engineering Workshop Locker Keypad Code Guide

- Jujutsu Kaisen Modulo Chapter 23 Preview: Yuji And Maru End Cursed Spirits

- God Of War: Sons Of Sparta – Interactive Map

- 8 One Piece Characters Who Deserved Better Endings

- Who Is the Information Broker in The Sims 4?

- Poppy Playtime 5: Battery Locations & Locker Code for Huggy Escape Room

- Pressure Hand Locker Code in Poppy Playtime: Chapter 5

- Mewgenics Tink Guide (All Upgrades and Rewards)

- Poppy Playtime Chapter 5: Emoji Keypad Code in Conditioning

- Why Aave is Making Waves with $1B in Tokenized Assets – You Won’t Believe This!

2026-02-22 18:19