Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have developed and analyzed function-correcting codes designed to ensure accuracy even when dealing with Boolean functions where outputs are heavily skewed.

This review characterizes optimal codes for maximally-unbalanced Boolean functions, analyzing their distance matrix properties and the trade-offs between data and function error correction under hard and soft decoding strategies.

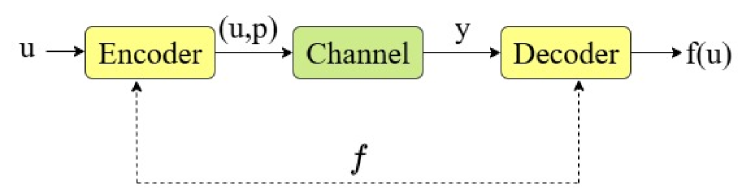

Reliable computation over noisy channels demands error correction strategies that prioritize function recovery over complete message reconstruction. This is the central challenge addressed in ‘Function Correcting Codes for Maximally-Unbalanced Boolean Functions’, where we investigate optimal single-error correcting codes designed for highly imbalanced Boolean functions. Our analysis reveals that the structure of these codes-specifically, their codeword distance matrices-significantly impacts error performance, leading to distinct trade-offs between correcting data errors and ensuring correct function evaluation. How can we best leverage code structure to optimize function recovery under varying decoding strategies and noise conditions?

Beyond Perfect Fidelity: Embracing Functional Resilience

Conventional error correction methodologies historically center on achieving bit-level fidelity, meticulously reconstructing the original data stream bit-by-bit. This approach, while robust for data storage and transmission, can be unnecessarily rigid when the ultimate goal isn’t perfect replication, but rather the successful execution of an intended function. Consider a control system: a slightly altered bit representing a temperature setpoint might still result in the desired heating outcome, rendering strict bit-level correction superfluous. This prioritization of exact data recovery often overlooks the inherent redundancy in many real-world applications, where multiple bit patterns can achieve the same functional result. Consequently, traditional codes can expend valuable resources correcting errors that have no practical impact on the overall system behavior, highlighting a disconnect between the means of correction and the desired end.

Consider applications ranging from medical diagnostics to autonomous vehicle control; in these scenarios, the precise bits representing sensor data or commands are less critical than the correct interpretation of that data. A slightly corrupted image might still be accurately identified as a stop sign, or a marginally imprecise measurement may still allow a life-saving dosage calculation. This prioritization of functional correctness over bit-level accuracy fundamentally alters the approach to error mitigation; it suggests that a system can remain reliably operational even with some degree of data corruption, provided the intended function – recognizing the sign, delivering the correct dose – is consistently achieved. This shift in focus necessitates coding schemes designed not simply to rebuild lost bits, but to guarantee the realization of the desired operational outcome, opening possibilities for robust systems operating in noisy or unreliable environments.

The demand for functional error correction arises from the limitations of conventional coding schemes, which primarily target bit-level accuracy without guaranteeing the successful execution of the intended operation. Consider applications where a slight deviation in data-a minor bit flip-doesn’t necessarily invalidate the overall purpose; a self-driving car, for example, needs to reliably interpret sensor data to act safely, not simply to record data perfectly. Therefore, codes designed to correct errors at a functional level prioritize the realization of the intended outcome, even if some underlying data corruption persists. This approach acknowledges that in many real-world scenarios, the effect of a message is more crucial than its precise form, paving the way for more robust and resilient systems capable of operating reliably despite noisy or imperfect data transmission.

Function Correcting Codes represent a significant departure from conventional error correction methods, which primarily aim to restore data to its exact original form. Instead of prioritizing bit-by-bit accuracy, these codes prioritize the successful execution of a desired function, even if the underlying data is imperfect. This paradigm shift acknowledges that in numerous real-world applications-such as control systems or machine learning-the ultimate goal isn’t flawless data transmission, but rather the reliable realization of a specific outcome. By encoding data in a way that guarantees the intended operation, even with some level of corruption, Function Correcting Codes enhance system robustness and offer a more practical approach to reliability, particularly in environments prone to noise or imperfect hardware. This focus on functional correctness opens doors to designing systems that are resilient not just to data errors, but to broader system imperfections as well.

Deconstructing Reliability: Building with Function in Mind

Systematic encoding is a fundamental principle in the construction of Function Correcting Codes (FCCs). This method ensures that the original message, or a direct representation of it, is explicitly included within the generated codeword. Unlike non-systematic codes where the message is obscured by encoding processes, systematic encoding maintains the message’s integrity as a recognizable subset of the codeword. This approach simplifies decoding procedures, as the message portion can be directly extracted, and allows for easier error detection and correction by focusing analysis on the added parity bits. The direct embedding of the message also facilitates code construction based on established encoding schemes and allows for predictable behavior during both transmission and recovery of the original data.

The Distance Requirement Matrix is fundamental to the construction of Function Correcting Codes, dictating the minimum Hamming distance necessary between all valid codewords. This matrix establishes a quantifiable threshold; if the Hamming distance between any two codewords falls below this threshold, the code will fail to correctly identify and resolve errors. Specifically, the matrix defines the number of differing bit positions required to distinguish each codeword from every other codeword in the code set, ensuring that any single-bit error or combination of errors within the defined error-correcting capability will result in a unique, identifiable codeword. The dimensions and values within the Distance Requirement Matrix directly correlate to the code’s error-correcting capacity (denoted as ‘t’) and the length of the codewords (denoted as ‘n’), effectively defining the code’s robustness against data corruption.

Maximally Unbalanced Boolean Functions are critical to enhancing Function Correcting Codes due to their specific pre-image characteristics. These functions, when used in code construction, ensure that each codeword has a unique pre-image, simplifying decoding processes and improving error detection capabilities. This uniqueness is achieved through the function’s property of producing an output of 0 for a significantly larger number of input combinations than 1. By leveraging this imbalance, codes can be designed to not only correct errors but also accurately identify the original message, even with multiple errors present, increasing the overall reliability and efficiency of the communication system. The degree of imbalance directly correlates with the code’s ability to distinguish between valid and invalid codewords.

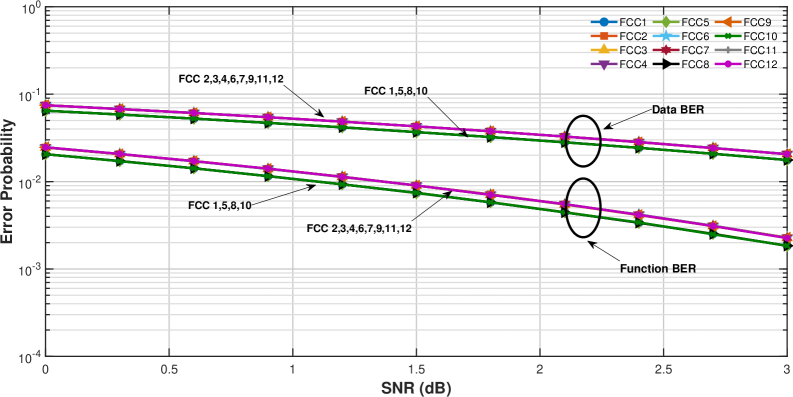

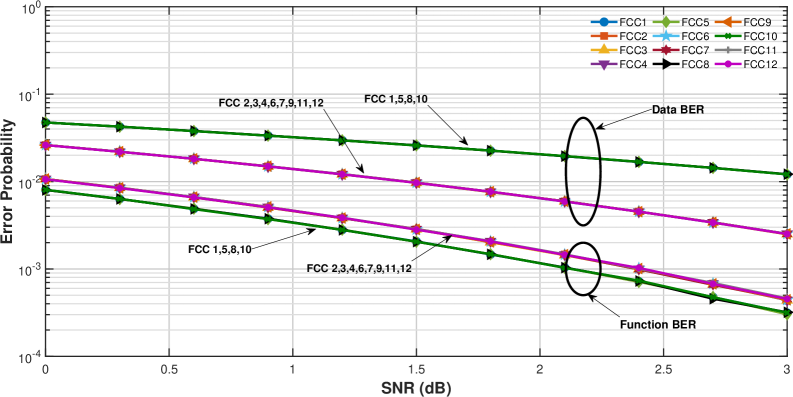

Analysis of the OR function within the framework of Function Correcting Codes has identified 12 distinct optimal Single-Error Correcting Function Correcting Codes (SEFCCs) achievable with a code length of k=2 and error-correcting capability of t=1. These codes represent the maximum possible number of codewords satisfying the criteria for single-error correction when applied to the OR function. Each of these 12 SEFCCs exhibits a minimum Hamming distance sufficient to uniquely identify and correct a single error within the codeword, ensuring accurate decoding of the original message. The specific configurations of these codes, detailing the codeword assignments, are detailed in accompanying documentation and represent a complete set of optimal solutions for this particular function and error-correction profile.

Decoding the Intent: Beyond Bit-Wise Correction

Decoding strategies in communication systems commonly utilize either hard-decision or soft-decision approaches, with performance significantly influenced by the prevailing noise characteristics of the transmission channel. Hard-decision decoding operates on quantized received signals, classifying them directly into the most probable transmitted bit. This method is effective in high signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) environments. Conversely, soft-decision decoding leverages the continuous amplitude of the received signal, providing more granular information and enabling more accurate decoding, particularly in low SNR scenarios where noise is substantial. The Additive White Gaussian Noise (AWGN) channel model is frequently used to analyze soft-decision performance. Consequently, while both methods achieve error correction, soft-decision decoding generally outperforms hard-decision decoding in noisy channels due to its ability to exploit subtle variations in the received signal.

Soft-decision decoding techniques offer performance gains over hard-decision decoding by utilizing the full information contained in the received signal, rather than simply classifying it as a 0 or 1. This is particularly effective when modeled using the Additive White Gaussian Noise (AWGN) channel, where the received signal is corrupted by Gaussian noise. Instead of discrete values, the decoder considers the continuous amplitude of the received signal, estimating the probability of each bit being a 0 or 1 based on its proximity to the decision boundary. This probabilistic approach allows the decoder to correct more errors, especially in low Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) conditions, as it can leverage partial information even when the signal is significantly degraded. The AWGN model provides a mathematically tractable framework for analyzing the performance of these decoders and optimizing decoding algorithms.

Hamming Distance is a fundamental metric used in error detection and correction within digital communication systems. It quantifies the number of bit positions at which two codewords differ. Specifically, it measures the minimum number of bit flips required to transform a received codeword into a valid codeword from the code’s library. A lower Hamming Distance indicates a greater similarity between the received signal and a valid codeword, suggesting a higher probability of correct decoding. Conversely, a higher Hamming Distance suggests a greater degree of error and potentially incorrect decoding. The calculation is performed bit-by-bit, and the resulting integer value provides a direct measure of the dissimilarity between the signals.

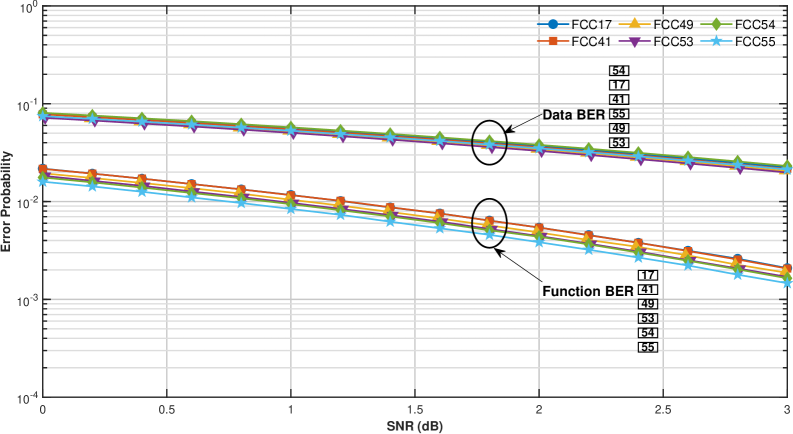

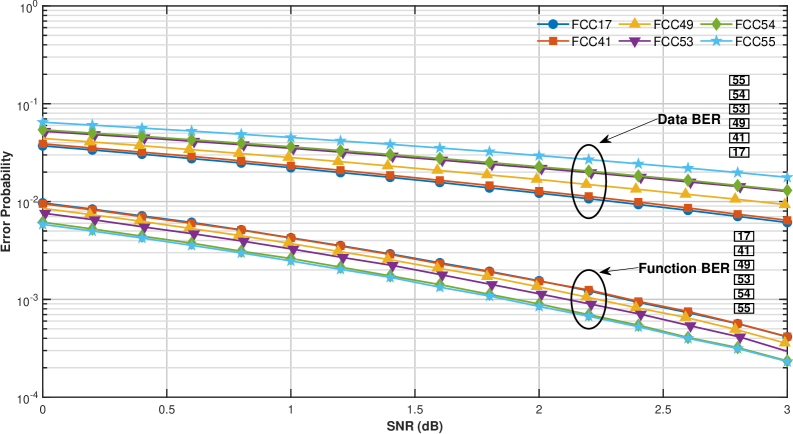

For a code with k=3 and designed to correct t=1 error, the analysis of Free Composition Codes (FCCs) reveals a complex codeword space. A total of 432 valid FCCs were examined, from which only 55 distinct distance matrices were identified. This indicates a significant reduction in the diversity of achievable codeword structures when considering the constraints of a single error correction capability and a block length of 3. The limited number of unique distance matrices, despite the large number of valid FCCs, suggests redundancy in the error correction capabilities offered by different code constructions within these parameters, and highlights the challenge of efficiently exploring the design space for optimal codes.

In soft-decision decoding schemes, the performance relationship between codeword distance matrices and bit error rates (BER) is quantifiable. Specifically, a higher sum of values along the upper-diagonal of the codeword distance matrix correlates with a lower Data BER, indicating improved performance in recovering the transmitted data bits. Conversely, a higher sum of values in the first row of the codeword distance matrix correlates with a lower Function BER, reflecting improved reliability in the decoded functional output. These correlations arise from the weighting of bit errors during the decoding process, where diagonal and first-row elements effectively represent the sensitivity of the decoding algorithm to specific error patterns.

Beyond Reproduction: Towards Inherently Robust Systems

Single-Error Correcting Function Correcting Codes represent a practical refinement of broader functional coding principles, specifically engineered to mitigate the impact of isolated errors during data transmission or storage. While traditional error correction focuses on restoring exact bit sequences, these codes prioritize the preservation of the intended function even if some bits are altered. This is achieved through a deliberate code construction that allows the receiver to reliably reconstruct the original functional output despite the presence of a single bit error. The codes accomplish this by introducing redundancy in a manner that maps multiple bit patterns to the same functional value, effectively creating a ‘tolerance’ for minor data corruption. This approach differs from standard Hamming codes or Reed-Solomon codes, which aim for precise bit recovery, and instead focuses on ensuring the overall computation or operation remains valid, proving particularly valuable in applications where resilience to minor data flaws is paramount.

Employing single-error correcting function codes in conjunction with Binary Phase-Shift Keying (BPSK) modulation offers a compelling strategy for bolstering communication reliability, particularly within challenging, noisy environments. BPSK, a simple yet effective modulation technique, represents data as phases of a carrier signal; however, these phases are susceptible to corruption during transmission. The function codes, designed to preserve the intended function of the data rather than exact bit replication, provide resilience against these errors. By strategically encoding information, these codes allow the receiver to correctly reconstruct the intended function even if a single bit is flipped due to noise. This combination is especially valuable in applications where the logical outcome of a computation is paramount, such as control systems or sensor networks, where a slightly corrupted value could lead to incorrect actions – and where ensuring functional correctness outweighs the need for perfect data recovery.

Continued advancements in functional coding rely heavily on refining both code construction and the algorithms used to interpret them. Researchers are actively exploring novel mathematical frameworks to design codes that not only correct errors but also minimize the computational complexity of decoding, a crucial factor for real-time applications. This includes investigating adaptive coding schemes that tailor the code’s structure to the specific characteristics of the communication channel or storage medium. By optimizing these elements, future codes promise to achieve significantly higher levels of functional reliability – ensuring that systems continue to operate correctly even in the presence of substantial noise or data corruption, and potentially exceeding the limitations of traditional error-correcting methods focused solely on bit-perfect reproduction.

Traditional communication and data storage prioritize accurate bit reproduction, assuming errors corrupt the entire message. However, a fundamentally different approach focuses on preserving the function of the information, even if some bits are altered. This paradigm shift is particularly valuable in applications where the overall result matters more than exact data fidelity – consider control systems, where a slightly imprecise signal is acceptable if the intended action is performed, or biological data storage, where approximate genetic information can still encode viable traits. By designing codes that guarantee functional correctness despite errors, systems can achieve unprecedented robustness and reliability, opening doors to resilient infrastructure and innovative data architectures that tolerate noise and degradation without losing essential operational capability.

The pursuit of optimal function-correcting codes, as detailed in this work, inherently embodies a spirit of controlled disruption. It isn’t enough to simply use a Boolean function; one must dissect its imbalances, probe its error-correcting capabilities, and ultimately, redefine its limits. This resonates with the insight of Henri Poincaré: “Mathematics is the art of giving reasons.” The paper’s rigorous analysis of distance matrices and decoding strategies isn’t merely about finding codes, but about understanding the fundamental relationship between data integrity and functional correctness – a reasoned exploration of the possible, achieved by questioning the assumed.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The pursuit of function-correcting codes, as demonstrated by this work, inevitably bumps against the inherent messiness of real-world data. Perfect correction, even for maximally-unbalanced functions, remains a theoretical ideal. The tidy distance matrices explored here offer insight, yet nature rarely cooperates with such elegant arrangements. Future investigations should deliberately introduce asymmetry – explore codes designed not for all errors, but for the likely errors encountered in specific, messy systems. Consider the performance hit when attempting universal correction, versus tailored resilience.

A particularly intriguing fault line lies in the interplay between hard and soft-decision decoding. The analysis reveals a trade-off, predictably, but the cost of that trade-off is surprisingly sensitive to the specific function being corrected. This suggests a path toward adaptive coding schemes – systems that dynamically adjust their correction strategy based on the function’s characteristics and the observed error distribution. It’s a move away from brute-force correction, towards a more nuanced, and ultimately, more efficient approach.

Ultimately, this work highlights a principle often overlooked: understanding a system isn’t about building something that never fails, but about understanding how it fails, and designing for graceful degradation. The most robust systems aren’t necessarily the most perfect; they are the ones that reveal their weaknesses most clearly, allowing for iterative improvement – a process far more honest, and arguably more effective, than striving for an unattainable ideal.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.10135.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- God Of War: Sons Of Sparta – Interactive Map

- Epic Games Store Free Games for November 6 Are Great for the Busy Holiday Season

- How to Unlock & Upgrade Hobbies in Heartopia

- Battlefield 6 Open Beta Anti-Cheat Has Weird Issue on PC

- Someone Made a SNES-Like Version of Super Mario Bros. Wonder, and You Can Play it for Free

- Sony Shuts Down PlayStation Stars Loyalty Program

- EUR USD PREDICTION

- The Mandalorian & Grogu Hits A Worrying Star Wars Snag Ahead Of Its Release

- One Piece Chapter 1175 Preview, Release Date, And What To Expect

- Overwatch is Nerfing One of Its New Heroes From Reign of Talon Season 1

2026-01-18 04:50