Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers demonstrate a practical attack that could isolate Ethereum nodes and disrupt network consensus after the Merge.

This review details the feasibility of eclipse attacks on Ethereum’s post-Merge peer-to-peer network, leveraging vulnerabilities in Discv4 node discovery.

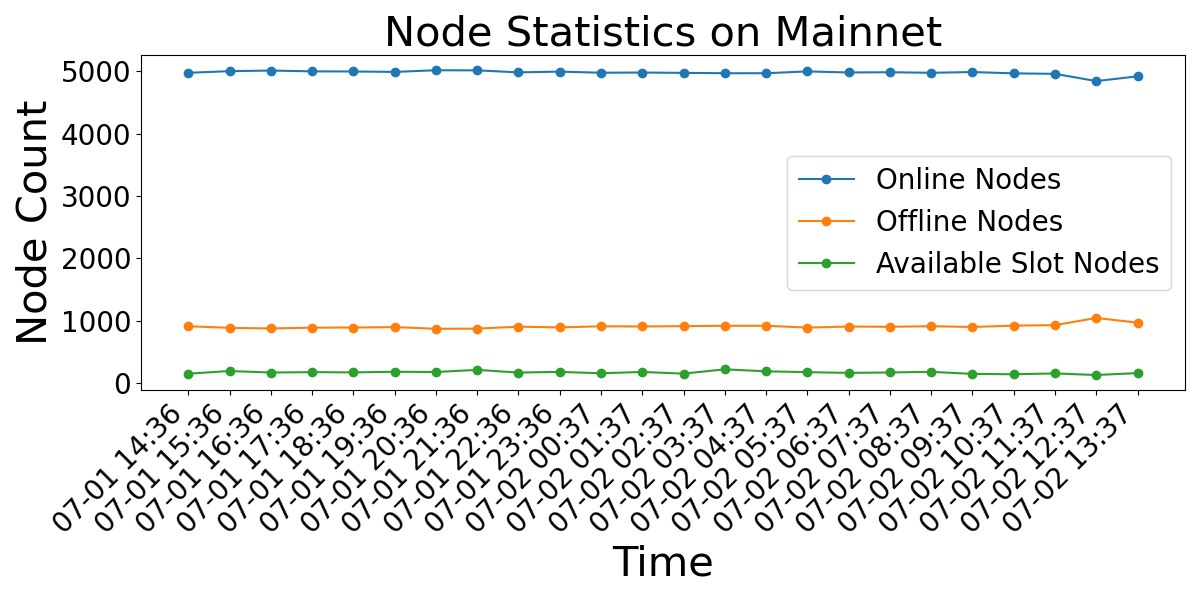

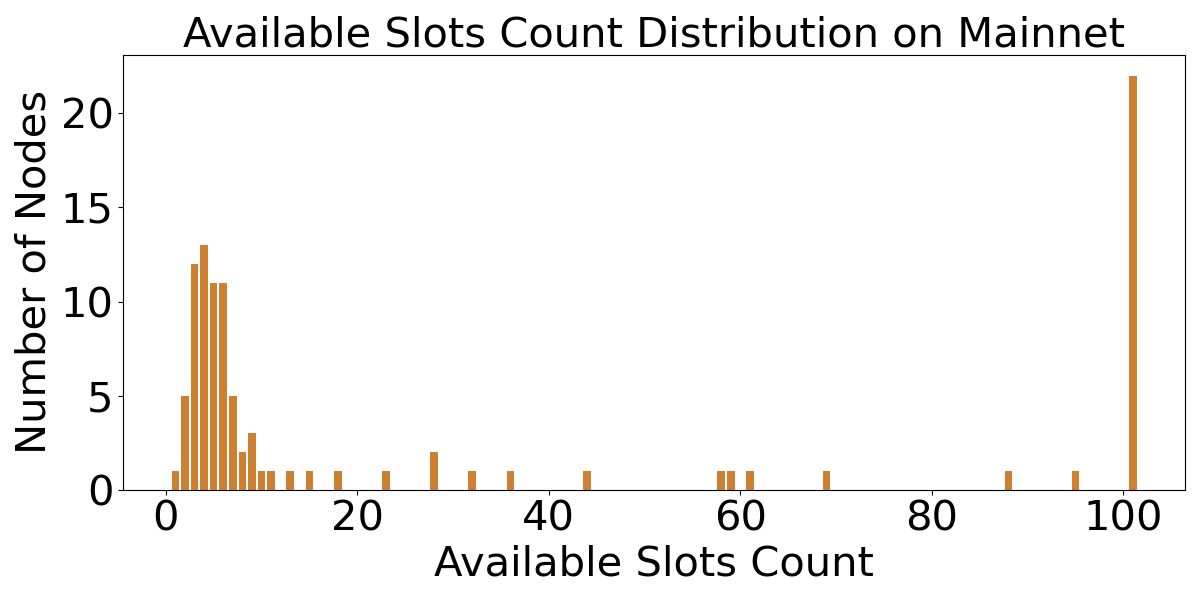

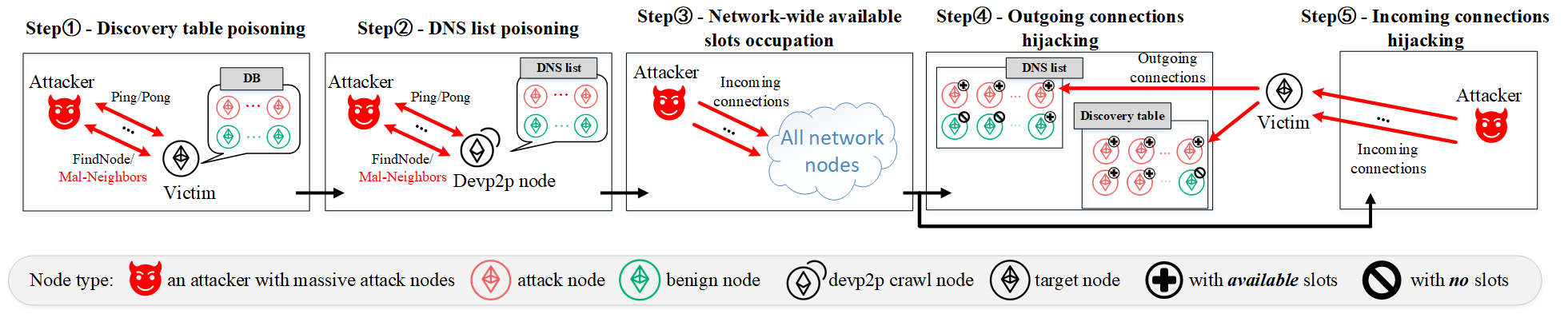

While blockchain networks are designed for resilience, vulnerabilities in peer-to-peer connectivity can undermine their security assumptions. This paper, ‘Eclipse Attacks on Ethereum’s Peer-to-Peer Network’, presents the first end-to-end implementation of an eclipse attack targeting Ethereum’s post-Merge execution layer, demonstrating the practical isolation of targeted nodes through manipulation of discovery and connection management. Our research reveals that over 80% of public Ethereum nodes lack sufficient capacity to resist such attacks, achieved via DNS poisoning requiring only 28 IP addresses and a novel slot hijacking technique. Does this widespread susceptibility necessitate a re-evaluation of Ethereum’s network security protocols and the robustness of its decentralized architecture?

The Evolving Foundation: From Proof-of-Work to Proof-of-Stake

Ethereum, in its earliest iterations, relied on Proof-of-Work to establish a secure and decentralized network. This mechanism demanded that miners compete to solve complex cryptographic puzzles – essentially, computationally intensive mathematical problems – to validate transactions and add new blocks to the blockchain. The first miner to successfully solve the puzzle broadcasted their solution to the network, and if verified by other participants, earned the right to add the block and receive newly minted ether as a reward. This process, while robust, required significant energy expenditure as miners invested in increasingly powerful hardware to maintain a competitive edge. The sheer computational effort served as the network’s primary defense against malicious actors, making it costly and difficult for anyone to attempt to manipulate the blockchain; however, it also presented limitations in terms of scalability and environmental sustainability, ultimately driving the need for alternative consensus mechanisms like Proof-of-Stake.

Ethereum’s move to Proof-of-Stake represents a significant architectural overhaul designed to address the limitations of its original Proof-of-Work system. Instead of miners competing to solve complex cryptographic puzzles, PoS relies on validators who ‘stake’ their existing Ether as collateral to participate in the consensus process. This fundamentally alters how the network achieves agreement and secures transactions. By eliminating the need for energy-intensive computation, PoS dramatically reduces Ethereum’s energy consumption-a key driver for the change. Furthermore, PoS is intended to enhance scalability; the system allows for a greater number of transactions to be processed efficiently, as validation isn’t constrained by computational power but rather by the amount of Ether staked and the validator’s operational reliability. This approach not only lowers the barrier to participation but also positions Ethereum for broader adoption and sustained growth.

The move from Ethereum’s original Proof-of-Work system to Proof-of-Stake represents a significant departure from traditional blockchain security models. While PoW relies on computational power to deter attacks – making them prohibitively expensive – PoS introduces a different set of vulnerabilities centered around validator behavior and stake distribution. Previously, an attacker needed to control over 50% of the network’s hashing power; now, acquiring 33.5% of the staked Ether could potentially allow for manipulation, though economic penalties are designed to disincentivize such actions. Furthermore, the long-range attack problem, where attackers attempt to rewrite blockchain history from a distant point, and the potential for correlated failures among validators represent novel challenges demanding ongoing research and mitigation strategies. This paradigm shift necessitates a reassessment of established security protocols and the development of innovative approaches to ensure the continued integrity and resilience of the Ethereum network.

The Beacon Chain represents a pivotal architectural component in Ethereum’s transition to Proof-of-Stake, functioning as the coordinating force for network consensus. Unlike Proof-of-Work, where miners competed to solve cryptographic puzzles, Proof-of-Stake relies on validators who ‘stake’ their Ether as collateral to participate in block creation and attestation. The Beacon Chain manages these validators, randomly assigning them duties and tracking their performance – rewarding honest behavior and penalizing malicious actions. It doesn’t directly process all Ethereum transactions; instead, it oversees the consensus process and coordinates a network of shard chains – parallel databases that collectively increase the network’s capacity. This centralized coordination, achieved through the Beacon Chain’s complex algorithms and validator management, ensures the integrity and security of the Ethereum network while dramatically reducing its energy consumption and paving the way for enhanced scalability.

The Network’s Visibility: Peer Discovery and the Eclipse Threat

Ethereum nodes utilize peer discovery protocols to establish and maintain network connectivity, a process essential for participation in the blockchain. Discv4 is a prominent example, serving as the current standard for node discovery within the Ethereum network. These protocols enable nodes to locate and connect with peers, facilitating data exchange – including block propagation and transaction verification – necessary for consensus. Without successful peer discovery, a node cannot effectively synchronize with the network, validate transactions, or participate in block creation, leading to isolation and ultimately, exclusion from the Ethereum ecosystem. The functionality relies on nodes broadcasting information about themselves and receiving similar broadcasts from others, building a dynamic map of available peers.

Discv4, the peer discovery protocol used by Ethereum nodes, initiates connection establishment via User Datagram Protocol (UDP) broadcasts. These broadcasts are used to locate potential peers within the network. The process relies heavily on DNS lists, which provide initial sets of node addresses. Upon receiving UDP responses, nodes populate and maintain a Discovery Table, a local cache of known peer information including IP addresses and supported network protocols. This table is dynamically updated as nodes exchange information, forming the basis for a node’s view of the network topology and influencing subsequent connection attempts. Efficient management of the Discovery Table is critical for network participation and responsiveness.

The Eclipse Attack poses a substantial risk to Ethereum node operation by enabling an adversary to dictate the network view of a targeted node. This is achieved by controlling the peers with which the victim node connects, effectively isolating it from the honest majority of the network. An attacker accomplishes this by manipulating the node’s incoming peer list, ensuring that the victim primarily, or exclusively, connects to attacker-controlled nodes. This control allows the attacker to feed the victim false or manipulated information about the blockchain state, potentially leading to consensus failures or denial-of-service conditions, as the victim operates on a distorted view of the network.

Attackers can manipulate a victim node’s network view by exploiting weaknesses in the Discv4 protocol’s peer discovery process. Specifically, manipulation of DNS lists used for initial node discovery allows attackers to advertise malicious nodes as peers. Simultaneously, attackers populate the victim’s Discovery Table – a local cache of known peers – with addresses they control. Our research demonstrates the practical feasibility of this eclipse attack; we successfully targeted nodes and established control over their peer connections by exploiting these vulnerabilities in discovery and connection mechanisms. This control allows the attacker to selectively filter or modify the information the victim node receives from the wider Ethereum network.

Fortifying the Network: Mitigating Eclipse Attacks

Eclipse attack success is frequently correlated with network configurations that lack dynamism and constrained incoming connection capacities. Static peer configurations, where a node consistently connects to the same peers, create predictable network topologies that attackers can exploit to isolate the target. Limited incoming connection capacity exacerbates this vulnerability; if a node has insufficient bandwidth or a low maximum connection limit, an attacker can more easily saturate available connections with malicious peers, effectively eclipsing legitimate connections. Observed data from the Sepolia testnet demonstrates this constraint, with nodes maintaining only approximately 30% of available connection slots compared to 3% on the mainnet, indicating a significantly reduced capacity to resist such attacks in constrained environments.

IP-Based Admission Limits and Incoming Connection Limits function as network-level defenses against Eclipse Attacks by restricting the rate and source of connection attempts to a node. IP-Based Admission Limits operate by tracking the number of connections originating from a single IP address; exceeding a pre-defined threshold results in subsequent connections from that IP being dropped. Incoming Connection Limits, conversely, enforce a maximum total number of concurrent connections a node will accept, regardless of origin. These limits prevent an attacker from overwhelming a node’s resources with a large volume of malicious peers, mitigating the risk of successfully establishing a compromised network view. Effective configuration of these limits requires balancing security with legitimate network participation, as overly restrictive settings can inadvertently block valid connections.

Eclipse attacks are complicated by advanced variants that go beyond simple flooding. The False Friends Attack involves malicious nodes advertising themselves with legitimate-appearing network identifiers and relaying false information about peer connectivity, disrupting the targeted node’s view of the network topology. The Connection Reset Attack actively interferes with established TCP connections by sending forged RST (reset) packets, forcing the victim node to repeatedly re-establish connections and increasing the attacker’s opportunity to control the peer set. These attacks necessitate defense strategies that move beyond basic rate limiting and incorporate robust peer verification and connection integrity checks.

Ethereum Node Records (ENR) are utilized within the Discv4 protocol to improve peer verification and establish trust between nodes. ENR provides a standardized method for nodes to advertise their network capabilities and identify themselves, reducing the risk of connecting to malicious peers. Analysis of network capacity on the Sepolia testnet revealed that nodes maintain approximately 30% of available connection slots, significantly higher than the 3% observed on the mainnet. This limited connection capacity on mainnet underscores the importance of efficient peer discovery and robust admission control mechanisms to prevent denial-of-service attacks and maintain network stability, while the higher capacity on Sepolia suggests potential scalability considerations for test environments.

Beyond Resilience: The Importance of Client Diversity

The foundation of a secure Ethereum network rests not on a single, monolithic client, but on the deliberate cultivation of diversity among them. Clients like Geth and Prysm, each built with different codebases and architectural approaches, act as crucial safeguards against unforeseen vulnerabilities. Should a flaw be discovered in one client, the network as a whole remains operational because other clients, unaffected by that specific issue, continue to validate transactions and maintain the blockchain. This redundancy dramatically reduces the risk of systemic failure and ensures the ongoing integrity of the network, functioning as a distributed defense mechanism against both known and, crucially, unknown threats. A homogenous network, conversely, presents a single point of failure, inviting potentially catastrophic consequences from a successful exploit.

An Eclipse Attack, while disruptive in itself, represents a significant stepping stone for more damaging exploits on the Ethereum network. Successful isolation of a node through manipulated peer connections allows an attacker to control the information that node receives, effectively creating a false reality. This manipulated view can then be leveraged to broadcast invalid transactions – appearing legitimate to the isolated node – and potentially execute double-spending attacks by confirming a transaction on the manipulated node while simultaneously attempting to reverse it on the broader network. Furthermore, attackers can exploit this control to manipulate smart contract interactions, triggering unintended consequences or siphoning funds by presenting a distorted state of the contract to the isolated node. The ability to dictate perceived blockchain state opens doors to a range of sophisticated attacks far exceeding simple denial of service, posing a critical threat to the integrity and security of decentralized applications.

The long-term viability of decentralized applications hinges directly on the robustness and security of the Ethereum network itself. As the foundational layer for a rapidly expanding ecosystem of decentralized finance, non-fungible tokens, and various Web3 innovations, Ethereum’s reliability is paramount. Any systemic weakness or vulnerability not only jeopardizes user funds and data but also erodes trust in the broader decentralized movement, potentially stifling innovation and hindering widespread adoption. A secure network fosters confidence among developers and users, encouraging continued investment and experimentation, while repeated security breaches can lead to regulatory scrutiny and a loss of public faith, ultimately limiting the potential of this transformative technology. Therefore, prioritizing network security isn’t merely a technical imperative; it’s a crucial factor in unlocking the full potential of decentralized applications and realizing a truly decentralized future.

Ongoing network security demands more than reactive measures; proactive monitoring and refined security protocols are paramount to addressing the ever-changing landscape of potential threats. Recent experimentation highlights the effectiveness of sophisticated attack vectors, demonstrating a concerning 95% success rate in hijacking outgoing connections under controlled conditions and achieving a 50% database pre-filling rate. These findings, coupled with observations that over 80% of incoming slots on the Sepolia testnet are consistently occupied, reveal a significant vulnerability for nodes operating near capacity. Such data underscores the need for continuous threat intelligence gathering, rigorous testing of security measures, and adaptive protocols designed to mitigate the risks posed by increasingly complex attacks and ensure the sustained stability of the Ethereum network.

The pursuit of robust network security often leads to elaborate designs, a tendency this study subtly mocks. It demonstrates how, despite the complexities of Ethereum’s post-Merge peer-to-peer network, a surprisingly straightforward eclipse attack remains viable. The researchers didn’t need to breach cryptographic protocols; they exploited inherent weaknesses in node discovery-specifically, the Discv4 mechanism-to isolate nodes. As Henri Poincaré observed, “It is better to have a few habits than many theories.” The elegance of this attack lies not in its sophistication, but in its simplicity, proving that sometimes, the most effective solutions are those stripped of unnecessary complexity. They called it a framework to hide the panic, but the panic was always about overcomplicating the core principles.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The demonstrated feasibility of an eclipse attack against Ethereum’s post-Merge network isn’t a revelation of fragility, but a necessary clarification. Security isn’t the absence of vulnerability, but the cost of exploitation. This work distills the problem to its essence: node discovery, specifically Discv4, remains a critical, and potentially economical, attack surface. The question isn’t whether attacks are possible, but whether they are worth executing, given the resources required versus the potential disruption.

Future inquiry should not focus on complex defenses, but on simplifying the discovery process itself. Reducing the reliance on peer-to-peer signaling, and perhaps incorporating a minimal, verifiable source of node addresses, offers a more direct, and therefore more intelligent, path toward resilience. The pursuit of perfect security is a fool’s errand; the aim should be sufficient security, achieved with minimal complexity.

Ultimately, this research serves as a reminder. Networks aren’t static fortresses, but dynamic systems. Security isn’t a destination, but a continuous process of reduction-stripping away unnecessary layers until only the essential defenses remain. The most effective security is often the most elegantly simple.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.16560.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- All Carcadia Burn ECHO Log Locations in Borderlands 4

- Enshrouded: Giant Critter Scales Location

- Best Finishers In WWE 2K25

- Best ARs in BF6

- Top 10 Must-Watch Isekai Anime on Crunchyroll Revealed!

- Poppy Playtime 5: Battery Locations & Locker Code for Huggy Escape Room

- All Shrine Climb Locations in Ghost of Yotei

- Top 8 UFC 5 Perks Every Fighter Should Use

- Keeping Agents in Check: A New Framework for Safe Multi-Agent Systems

- Scopper’s Observation Haki Outshines Shanks’ Future Sight!

2026-01-26 20:06