Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new approach to constructing gravitational wave signals significantly speeds up data analysis by efficiently building the necessary mathematical basis.

This work introduces a multibanding strategy for reduced order quadrature techniques to accelerate parameter estimation in gravitational wave inference.

Efficiently estimating parameters from gravitational wave signals requires navigating a computationally expensive likelihood calculation; this is particularly true for longer signals and complex models. In this work, ‘Multibanded Reduced Order Quadrature Techniques for Gravitational Wave Inference’, we present a modified construction strategy for reduced-order quadrature (ROQ) bases, leveraging multiband waveforms to accelerate the basis search without sacrificing accuracy. This approach yields a 20-30% reduction in basis size and a tenfold decrease in construction time using the \texttt{IMRPhenomXAS\_NRTidalV3} waveform model. Will these techniques unlock even faster and more accurate parameter estimation for forthcoming gravitational wave observatories and complex astrophysical scenarios?

Decoding the Cosmos: The Challenge of Gravitational Wave Detection

The detection of gravitational waves hinges on a computationally demanding process of waveform matching. Incoming signals, ripples in spacetime predicted by Einstein’s theory of general relativity, are incredibly faint and buried within noise. Identifying these signals requires comparing them to a vast library of theoretically predicted waveforms, each representing a different possible astrophysical event – such as the collision of two black holes or neutron stars. This comparison isn’t simple; the observed signal must be precisely aligned in time and amplitude with the theoretical template to confirm a detection. The complexity arises because these waveforms aren’t static; they evolve over time and are sensitive to numerous parameters defining the source, including its mass, spin, and distance. Effectively, the search becomes a high-dimensional needle-in-a-haystack problem, necessitating immense computational resources and sophisticated algorithms to sift through the data and confidently identify genuine gravitational wave events.

The pursuit of gravitational waves is hampered by an inherent complexity: the sheer number of variables defining a detectable signal. Each gravitational wave event is characterized by parameters like the masses of the colliding objects, their spins, the distance to the source, and the angle of observation – creating a multi-dimensional ‘parameter space’ that traditional computational methods struggle to navigate efficiently. As the number of dimensions increases, the computational cost of searching this space grows exponentially, demanding ever more processing power to identify potential matches between observed signals and theoretical predictions. This ‘curse of dimensionality’ necessitates innovative approaches, such as reduced-order modeling and machine learning techniques, to effectively extract meaningful information from the deluge of data and unlock the secrets hidden within these ripples in spacetime.

The precision with which gravitational waves can be detected hinges on accurately determining the intrinsic parameters of the merging black holes or neutron stars that create them. Key quantities like chirp mass – a combination of the masses of the two objects – mass ratio, and the magnitude and direction of their spins, profoundly affect the observed waveform. However, each of these parameters exists within a multi-dimensional space, and fully exploring this space to find the best-fit values is a computationally demanding task. The complexity arises because even small uncertainties in these parameters can significantly alter the predicted signal, requiring extensive calculations to ensure a reliable match with detector data. Consequently, researchers are continually developing innovative algorithms and employing advanced computational resources to efficiently navigate this high-dimensional parameter space and extract the most precise astrophysical information from these fleeting cosmic events.

Accelerating Discovery: Reduced Order Quadrature for Gravitational Wave Inference

Reduced Order Quadrature (ROQ) accelerates likelihood evaluations by representing complex functions with fewer frequency samples than traditional methods. This reduction in sampling points directly translates to computational savings, as the evaluation of the likelihood function – a core operation in many statistical inference tasks – becomes less demanding. By approximating the original function with a reduced set of basis functions derived from strategically chosen frequencies, ROQ minimizes the computational cost associated with high-dimensional integration, which is inherent in likelihood calculations. This approach is particularly beneficial when dealing with computationally intensive models or large datasets where frequent likelihood evaluations are required.

Effective Reduced Order Quadrature (ROQ) relies on the careful construction of its basis functions to accurately represent the underlying probability distributions. Multibanding is a key technique employed in this construction, involving the partitioning of the frequency domain into multiple, non-overlapping bands. This allows for localized optimization of frequency resolution within each band, concentrating computational effort where it is most needed to capture essential spectral features. By adaptively refining resolution based on band-specific characteristics, multibanding minimizes the number of frequency samples required to achieve a desired level of accuracy, directly impacting the efficiency of likelihood evaluations and overall inference speed.

The PyROQ code is a Python package designed to facilitate the construction and application of reduced order quadrature (ROQ) bases for accelerated inference. It provides functions for generating these bases using techniques such as multibanding, allowing users to control frequency resolution and basis size. The library includes tools for efficiently evaluating likelihood functions with the constructed bases, and supports both linear and more complex basis types. PyROQ is designed to be integrated into existing probabilistic programming workflows, offering a practical means to implement ROQ-based acceleration without requiring substantial modifications to underlying models or inference procedures.

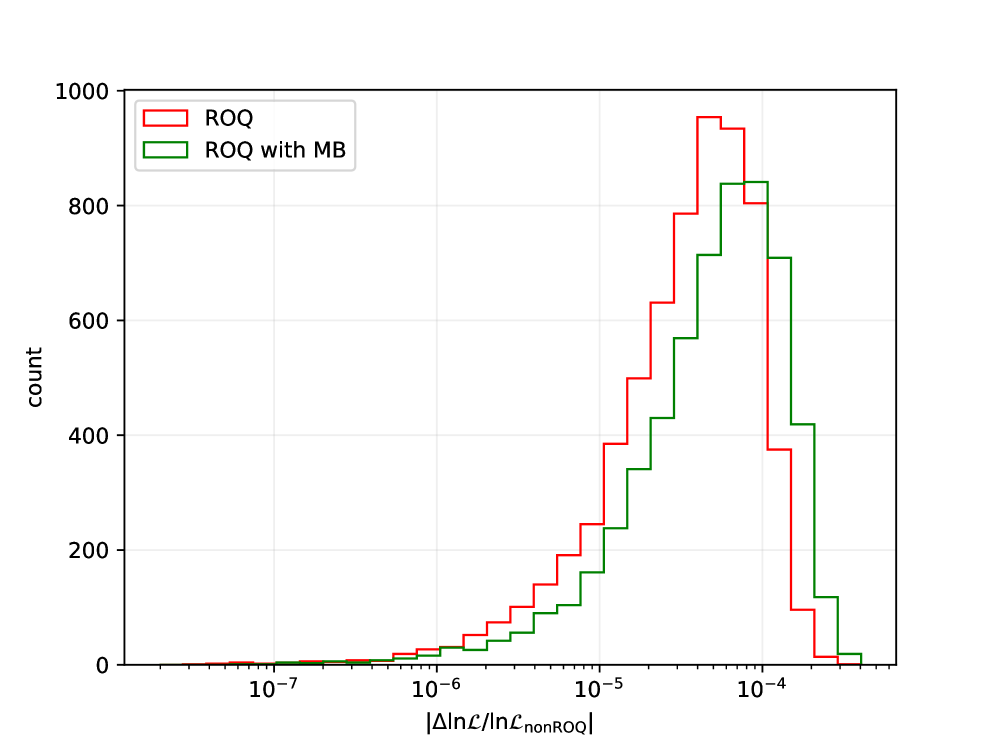

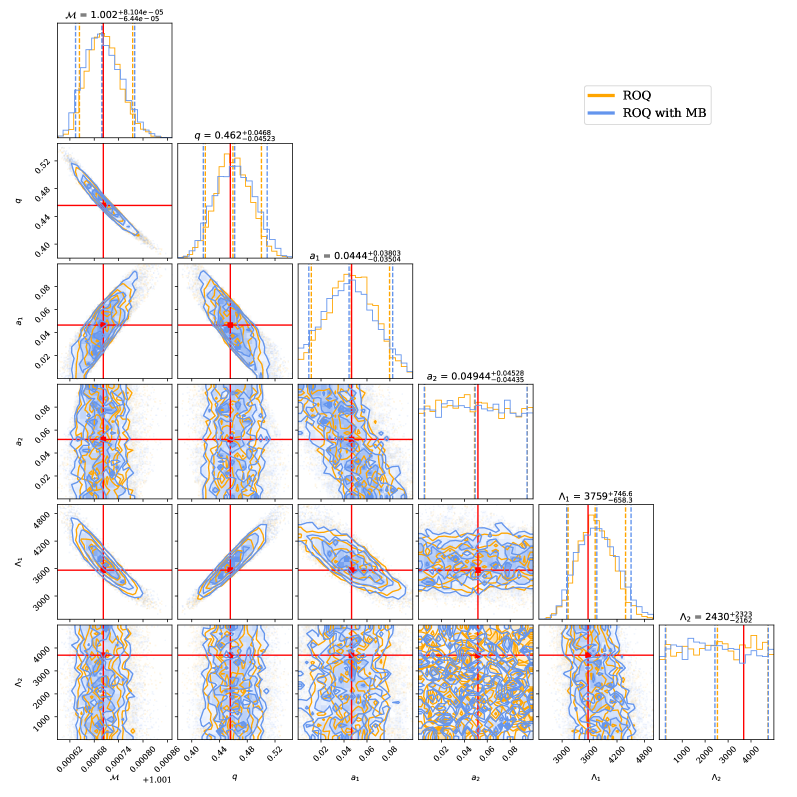

A modified Reduced Order Quadrature (ROQ) construction strategy demonstrably improves performance metrics compared to the standard PyROQ implementation. Specifically, this approach achieves a 30% reduction in basis size while simultaneously realizing a 13x speedup in basis construction time. These gains are observed when utilizing linear bases; performance with other basis types may vary. This enhanced efficiency stems from optimized likelihood function evaluation within the ROQ construction process, enabling faster computation with a smaller basis set.

Bayesian Frameworks and Waveform Fidelity: The Foundation of Precise Inference

Bayesian parameter estimation is a statistical method used to determine the values of source parameters, such as mass and spin, given observational data. This process begins with defining a prior probability distribution representing existing knowledge or assumptions about these parameters. This prior is then combined with the likelihood function, which quantifies the compatibility of the observed data with different parameter values. The resulting posterior probability distribution, calculated using Bayes’ theorem P(\theta|d) \propto P(d|\theta)P(\theta), represents the updated knowledge of the parameters after considering the data, where θ represents the parameters, d represents the data, P(\theta) is the prior, and P(d|\theta) is the likelihood. By sampling from this posterior distribution, credible intervals can be established, providing a range of plausible values for each source parameter and quantifying the uncertainty in their estimation.

The BILBY framework is a Python package designed for performing Bayesian inference, specifically for gravitational wave data analysis. It automates the likelihood calculation, prior definition, and sampling processes required for parameter estimation. BILBY integrates with various sampling algorithms, with Dynesty being a particularly effective choice due to its implementation of dynamic nested sampling. This allows for efficient exploration of the parameter space and robust estimation of credible intervals. Furthermore, BILBY provides tools for handling data conditioning, noise modeling, and the generation of posterior probability distributions, streamlining the process of comparing theoretical waveforms to detector observations and quantifying the uncertainties in estimated source parameters.

Accurate gravitational waveform modeling is critical for Bayesian parameter estimation, and the IMRPhenomXAS_NRTidalv3 model represents a state-of-the-art approach for simulating signals from merging compact binaries. This model incorporates post-Newtonian approximations to general relativity, extended to include tidal effects from neutron star deformation, and is specifically designed for signals detected by ground-based interferometers. IMRPhenomXAS_NRTidalv3 provides a frequency-domain waveform that accurately represents the signal’s amplitude and phase evolution throughout the inspiral, merger, and ringdown phases, enabling a robust comparison with detector data. The model’s accuracy directly impacts the precision with which source parameters – such as component masses, spins, and distance – can be inferred from observed gravitational wave signals.

The overlap integral provides a quantitative measure of the correlation between a gravitational wave signal model and detector data, effectively determining how well the model explains the observed signal. Calculated as 4\Re \in t_0^\in fty \frac{h^<i>(f)h(f)}{S_n(f)} df , where h(f) represents the Fourier transform of the waveform, h^</i>(f) is its complex conjugate, and S_n(f) denotes the power spectral density of the detector noise, the integral assesses the degree of alignment between the signal and data in the frequency domain. A higher overlap value indicates a greater similarity, with the maximum possible overlap of 1 representing a perfect match, while values approaching 0 indicate minimal correlation; the sensitivity of parameter estimation is directly influenced by the magnitude of this overlap.

Unveiling the Cosmos: The Broader Implications and Future of Gravitational Wave Astronomy

Recent computational breakthroughs are revolutionizing the study of binary systems – pairings of objects like neutron stars and black holes locked in a cosmic dance. These advancements allow researchers to model the complex interactions within these systems with unprecedented detail, moving beyond simplified approximations. By simulating the gravitational waves emitted as these objects spiral inward and ultimately collide, scientists can now scrutinize the properties of incredibly dense matter found within neutron stars, and rigorously test the predictions of general relativity in extreme environments. This detailed modeling isn’t just about confirming existing theories; it opens the door to potentially discovering new physics by revealing subtle deviations from expected behavior, ultimately refining humanity’s understanding of the universe’s most enigmatic objects.

The precise measurement of tidal deformability in compact objects like neutron stars offers a unique window into the behavior of matter at extreme densities, far beyond what can be replicated in terrestrial laboratories. As two neutron stars spiral inward before merging, their immense gravity warps spacetime, and each star subtly deforms under the influence of the other’s gravitational field – this is tidal deformation. The degree of this deformation is directly linked to the equation of state, which describes the relationship between pressure and density within the neutron star. By analyzing gravitational waves emitted during such mergers, scientists can infer the tidal deformability and, consequently, constrain the possible equations of state, potentially revealing the composition and fundamental properties of matter at densities exceeding 10^{17} \text{ kg/m}^3. This provides crucial insights into the nature of dense matter, helping to determine if neutron stars contain exotic forms of matter, such as quarks or hyperons, and ultimately refining models of stellar structure and evolution.

The precision gained through enhanced parameter estimation is fundamentally reshaping the landscape of gravitational wave astronomy, offering unprecedented opportunities to rigorously test the predictions of Einstein’s general relativity. By more accurately determining the intrinsic properties of merging compact objects-such as mass, spin, and distance-scientists can subject the theory to increasingly stringent tests in extreme gravitational regimes. Deviations from general relativity, however subtle, could manifest as inconsistencies in these parameters, potentially signaling the presence of new physics beyond the Standard Model. This includes exploring alternative theories of gravity, searching for evidence of extra dimensions, or even constraining the properties of dark matter and dark energy, making gravitational wave analysis a powerful tool for fundamental discovery.

The computational method detailed in this research achieves a remarkably low likelihood error – less than 7 x 10-3 when compared to full likelihood calculations – validating the accuracy of the reduced-order quadrature technique. This precision is not merely academic; it directly translates to significantly faster and more efficient gravitational wave analysis. By streamlining the complex calculations required to interpret signals from cataclysmic cosmic events, researchers can now explore a greater volume of data and, crucially, conduct more comprehensive tests of fundamental physics, including general relativity and the behavior of matter at extreme densities. The demonstrated efficiency paves the way for real-time gravitational wave detection and a deeper understanding of the universe’s most enigmatic phenomena.

The presented work on multibanded reduced order quadratures directly addresses the computational demands of gravitational wave inference. It’s a pragmatic step toward efficiently navigating complex parameter spaces-a necessity when dealing with the sheer volume of data these signals generate. This pursuit of scalable computation without careful consideration of underlying assumptions echoes a broader concern. As Ralph Waldo Emerson stated, “Do not go where the path may lead, go instead where there is no path and leave a trail.” The research doesn’t simply follow established methods but forges a new path, acknowledging the need for innovation in waveform construction and likelihood approximation to achieve faster, more accurate Bayesian inference. However, scalability must be paired with a rigorous understanding of the approximations inherent in reducing the basis size-otherwise, acceleration becomes directionless.

What Lies Ahead?

The acceleration of gravitational wave inference, as demonstrated by this work, is not merely a technical achievement. It is a sharpening of the lens through which humanity observes the universe-and, crucially, a magnification of the biases embedded within the observational process. Every reduction in computational cost, every streamlined algorithm, necessitates a corresponding interrogation of the assumptions made in its construction. The promise of rapidly surveying the cosmos carries the implicit responsibility of acknowledging the worldview encoded in each waveform model, each likelihood approximation.

Future investigations should not focus solely on further algorithmic efficiency. The true challenge resides in developing robust methods for quantifying and mitigating the systematic errors inherent in these approximations. Multibanding, while effective for signal representation, does not inherently address the problem of model inadequacy. Indeed, it may exacerbate it by allowing researchers to explore wider parameter spaces with potentially flawed foundations. A parallel effort must be devoted to validation techniques-independent checks on the fidelity of these increasingly complex simulations.

The speedups achieved through reduced order quadrature are, in a sense, a distraction. The more profound question is not how quickly can signals be processed, but what is being sought within those signals. The construction of these inference pipelines is not a neutral act; it defines the boundaries of what is considered ‘signal’ and what is dismissed as ‘noise’. Privacy interfaces are forms of respect, and similarly, transparent model building is an acknowledgement of the inherent limitations of any observational science.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.09819.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- God Of War: Sons Of Sparta – Interactive Map

- Poppy Playtime 5: Battery Locations & Locker Code for Huggy Escape Room

- Someone Made a SNES-Like Version of Super Mario Bros. Wonder, and You Can Play it for Free

- Overwatch is Nerfing One of Its New Heroes From Reign of Talon Season 1

- Poppy Playtime Chapter 5: Engineering Workshop Locker Keypad Code Guide

- Why Aave is Making Waves with $1B in Tokenized Assets – You Won’t Believe This!

- One Piece Chapter 1175 Preview, Release Date, And What To Expect

- Meet the Tarot Club’s Mightiest: Ranking Lord Of Mysteries’ Most Powerful Beyonders

- Bleach: Rebirth of Souls Shocks Fans With 8 Missing Icons!

- All Kamurocho Locker Keys in Yakuza Kiwami 3

2026-01-17 03:33