Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new study reveals how inaccuracies in speech-to-text transcription can significantly hinder understanding of spoken code, especially for learners and in multilingual settings.

Researchers propose a speech-driven framework combining automatic speech recognition with large language model refinement to improve code accessibility and accuracy.

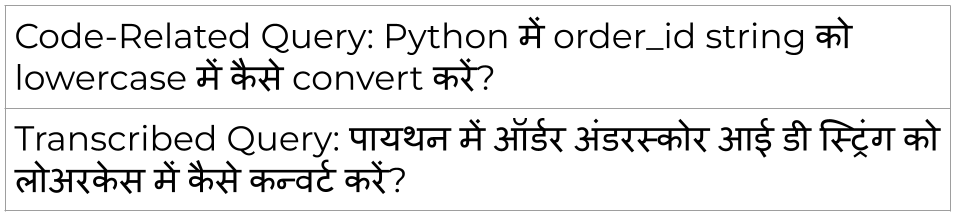

While voice interfaces promise more inclusive access to programming tools, current speech-to-text systems often struggle with the unique challenges of code-related queries. This work, ‘Lost in Transcription: How Speech-to-Text Errors Derail Code Understanding’, introduces a multilingual speech-driven framework that leverages large language models to refine automatic speech recognition output and improve code understanding across multiple Indic languages and English. Our findings demonstrate that LLM-guided refinement significantly mitigates the impact of transcription errors on downstream tasks like code question answering and retrieval. How can we further adapt speech interfaces to robustly handle the complexities of code and empower a more diverse range of developers?

The Illusion of Seamless Interaction

For decades, interacting with computers to create code has fundamentally depended on text-based systems – keyboards, text editors, and command-line interfaces. This reliance presents significant obstacles for individuals new to programming, who must simultaneously learn both the logic of coding and the mechanics of precise text input. Beyond novices, this traditional approach also excludes those who might prefer, or be more efficient with, spoken communication. The barrier isn’t merely about physical access; it’s a cognitive load that demands attention be divided between conceptualizing an algorithm and accurately translating it into written syntax. Consequently, a substantial portion of potential programmers, or those seeking more intuitive methods, are effectively locked out of directly expressing their computational ideas, hindering broader participation in the creation of technology.

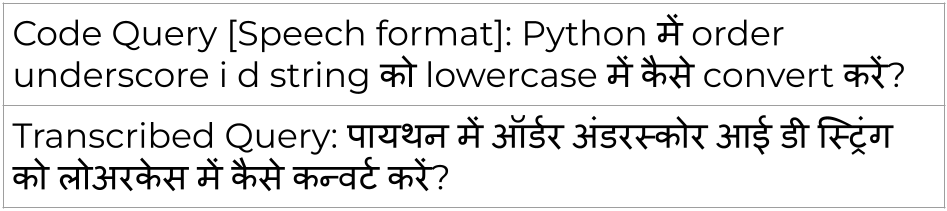

The precision of converting spoken language into text is paramount when interacting with code, yet conventional Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) systems frequently falter in this domain. Standard ASR models, trained on general language corpora, often lack familiarity with the specialized vocabulary and strict grammatical rules inherent in programming languages. This unfamiliarity manifests as higher Word Error Rates when transcribing code-related terms – keywords, function names, and syntax – compared to natural language. The challenge isn’t simply recognizing words, but accurately interpreting sequences that hold specific meaning within a coding context, making reliable speech-to-code transcription a uniquely difficult task for typical ASR technology.

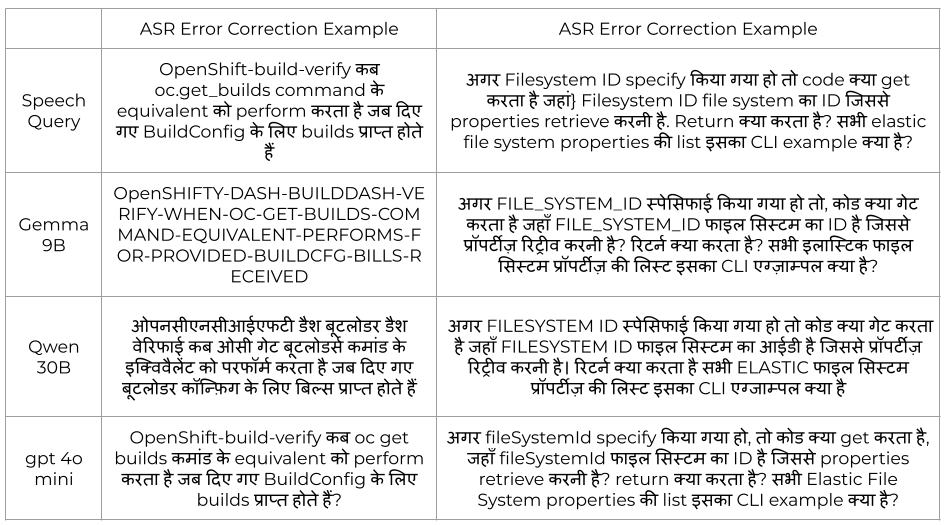

Effective speech-driven coding interfaces demand more than simply converting spoken words to text; they require a system capable of understanding and correcting the unique language of code. Initial speech recognition, while improving, frequently misinterprets technical terms and precise syntax, leading to errors that hinder usability. Recent advancements demonstrate that integrating Large Language Models (LLMs) to refine these transcriptions specifically for code-related content significantly improves accuracy. This post-processing step, leveraging the LLM’s understanding of programming languages, has demonstrably reduced Word Error Rates by over 20%, creating a more reliable and intuitive experience for developers who prefer or require voice-based interaction with their code.

The Framework: A Pragmatic Approach

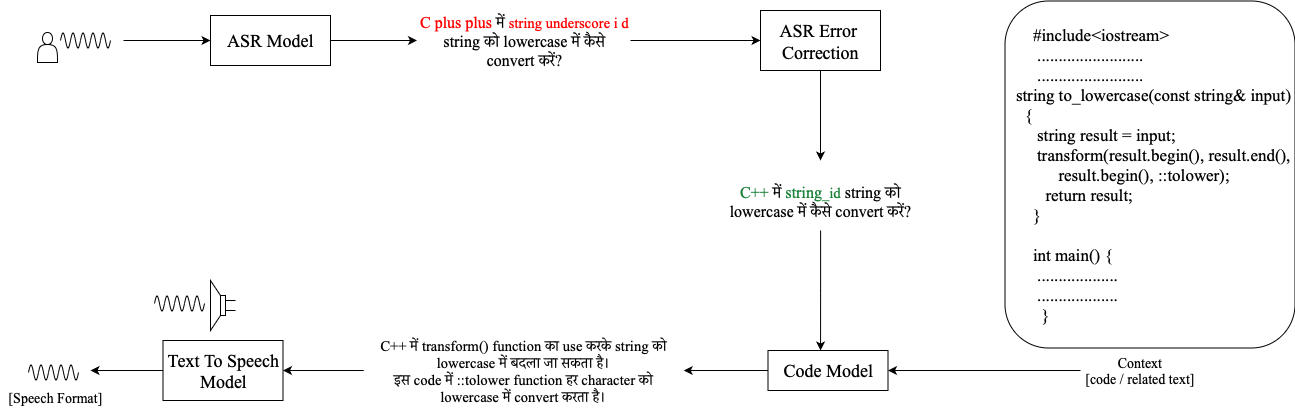

The Speech-Driven Framework enables developers to interact with code using spoken language. This system accepts natural language queries as input and translates them into commands executable within a development environment. The core functionality centers on converting vocalizations into actionable code operations, such as navigating files, executing functions, and modifying code blocks. This hands-free approach aims to improve developer efficiency and accessibility by removing the need for traditional input methods like keyboards and mice, particularly beneficial in situations where these methods are impractical or impossible to use.

The Speech-Driven Framework incorporates a Code-Aware Transcription Refinement process following Automatic Speech Recognition (ASR) to improve the accuracy of code-related spoken input. This process leverages Large Language Models (LLMs) specifically trained to identify and correct transcription errors common in programming terminology. By applying LLM-based refinement, the framework achieves a 19.9% Word Error Rate (WER) on code-related queries, representing a significant improvement over standard ASR systems when dealing with technical vocabulary and syntax.

The Speech-Driven Framework incorporates multilingual programming support, enabling code interaction via spoken commands in multiple languages beyond English. This functionality expands accessibility to developers and learners who may not be proficient in English, or who prefer to utilize their native language for coding tasks. The system currently supports transcription and interpretation of spoken code commands in Spanish, Mandarin, and German, with ongoing efforts to integrate additional languages based on user demand and linguistic data availability. This broader language support facilitates a more inclusive development environment and promotes wider adoption of voice-driven coding tools.

Evidence: A Numbers Game, Ultimately

Code Retrieval and Question Answering serve as primary evaluation methods for the framework, directly reflecting its utility in interactive code exploration scenarios. These downstream tasks assess the system’s ability to accurately identify relevant code snippets given a natural language query, and to provide concise answers based on code content. Successful performance in these areas indicates the framework’s effectiveness in supporting developers during tasks such as code understanding, debugging, and modification. The framework is designed to facilitate a more fluid and efficient interaction between developers and codebases, and these tasks provide quantifiable metrics for measuring that improvement.

Performance benchmarking utilizes established datasets – CodeSearchNet, CoRNStack, and CodeQA – to quantitatively assess the system’s accuracy and efficiency in code retrieval tasks. Evaluations, conducted with refined queries, demonstrate a Recall@5 metric of 90%, indicating that 90% of the time, a relevant code snippet is present within the top 5 retrieved results. This metric provides a standardized measure of the system’s ability to identify and return pertinent code examples based on a given query, facilitating objective comparison with other models and tracking performance improvements.

Performance comparisons were conducted against several established models – Whisper, Indic-Conformer, Qwen-3-Omni-Flash, and Phi-4-multimodal-instruct – to evaluate the proposed framework. Results indicate a superior performance, as measured by a Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR) of 83.78% when evaluating the top 5 retrieved results (k=5). The MRR metric assesses the average inverse rank of the first relevant document, providing a standardized measure of retrieval effectiveness across the tested models and datasets.

The Illusion of Progress, and What Comes Next

A novel speech-driven framework is poised to democratize programming by allowing individuals to interact with code using everyday language. Traditionally, learning to code requires mastering specific syntax and commands, presenting a significant hurdle for many potential developers. This system bypasses that requirement, interpreting spoken instructions and translating them into functional code or modifications. The implications are substantial; aspiring programmers can now conceptualize and build software without the initial frustration of complex coding languages, fostering creativity and innovation. This approach not only lowers the barrier to entry but also opens doors for individuals with limited typing skills or those who prefer verbal communication, potentially unlocking a wider pool of talent in the field of computer science.

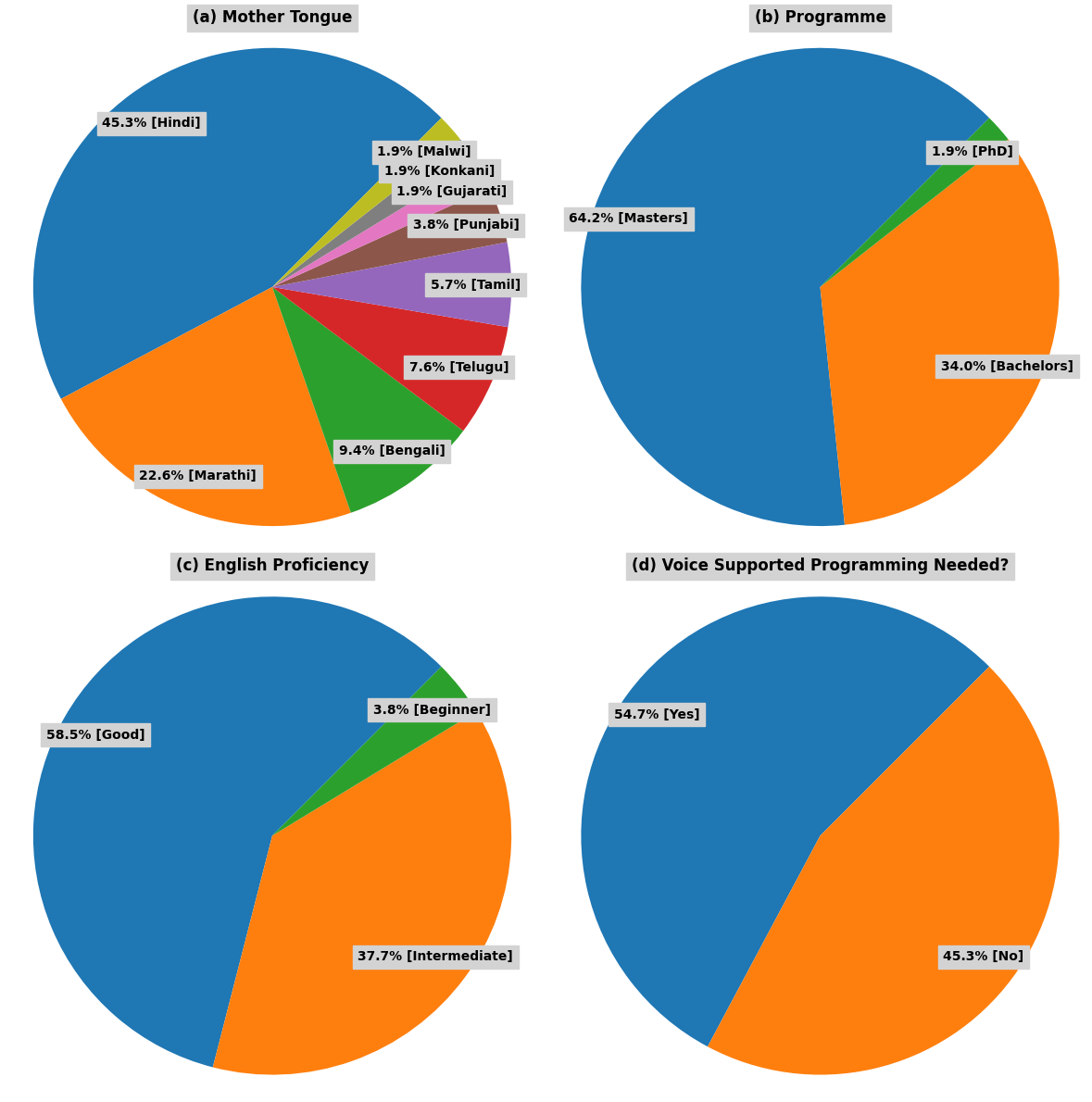

The framework’s capacity to process and generate code in low-resource languages-those with limited digital resources and fewer available datasets-represents a significant step towards democratizing programming access worldwide. Historically, programming education and collaborative development have been heavily skewed towards languages like English, creating barriers for individuals and communities where these languages are not prevalent. By extending functionality to encompass a wider range of languages, the framework unlocks opportunities for participation from previously excluded populations, fostering a more inclusive and globally representative programming landscape. This broadened reach not only facilitates learning but also encourages the development of localized applications and solutions tailored to the specific needs of diverse communities, ultimately driving innovation on a global scale.

Further development of this speech-driven programming framework centers on integrating multimodal learning, allowing the system to process information beyond just spoken language – potentially incorporating visual cues like diagrams or handwritten code sketches. This expansion aims to create a more intuitive and versatile interface for programmers of all skill levels. Simultaneously, research is being directed toward leveraging the framework’s capabilities for automated code generation, where natural language instructions are directly translated into functional code, and for intelligent debugging assistance, where the system can identify and suggest corrections for errors based on spoken descriptions of the problem – ultimately streamlining the software development process and fostering innovation.

The pursuit of seamless speech-to-text integration with code understanding, as detailed in this framework, feels predictably optimistic. It’s a valiant attempt to bridge the gap between natural language and machine execution, yet one can’t help but anticipate the inevitable cascade of errors that production will introduce. As Vinton Cerf observed, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” The ‘magic’ of translating spoken instruction into functional code, however, quickly reveals its limitations. The paper’s focus on multilingual programming and refining ASR specifically for code is commendable, but architecture isn’t a diagram; it’s a compromise that survived deployment. The inevitable drift from ideal transcription to practical, usable code is not a failure, merely an acknowledgment that everything optimized will one day be optimized back.

What’s Next?

The pursuit of speech-driven code understanding, as demonstrated, inevitably bumps against the limitations of automatic speech recognition. Refinement via large language models offers marginal gains, but primarily addresses symptoms, not the core issue: ASR systems aren’t designed for the precise vocabulary and syntax of programming languages. Expect a proliferation of ‘code-aware’ ASR models – more complexity layered onto existing systems, and thus, more points of failure. The promise of multilingual accessibility is admirable, but the reality will be uneven performance across languages, with the usual power imbalances replicated in algorithmic form.

This work highlights a familiar pattern. A theoretically elegant solution – direct speech-to-code – is quickly burdened by the messiness of real-world input. The field will likely fragment. Some will chase ever-more-sophisticated ASR, others will focus on error correction at the LLM level, and a pragmatic few will accept that some level of manual intervention is unavoidable. If code looks perfect after voice input, it’s a strong indication no one has actually tried to compile it.

The long game isn’t about eliminating transcription errors; it’s about minimizing their impact. Expect research to shift toward robust parsing techniques that can gracefully handle noisy input, and towards tools that provide intelligent suggestions and automated fixes. Ultimately, this work serves as a reminder that ‘MVP’ doesn’t mean ‘minimum viable product’; it means ‘minimum viable…patchwork’.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.15339.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Enshrouded: Giant Critter Scales Location

- All Carcadia Burn ECHO Log Locations in Borderlands 4

- Best Finishers In WWE 2K25

- Poppy Playtime 5: Battery Locations & Locker Code for Huggy Escape Room

- Top 10 Must-Watch Isekai Anime on Crunchyroll Revealed!

- Top 8 UFC 5 Perks Every Fighter Should Use

- Best Anime Cyborgs

- All Shrine Climb Locations in Ghost of Yotei

- Best ARs in BF6

- Keeping Agents in Check: A New Framework for Safe Multi-Agent Systems

2026-01-25 01:48