Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals an unexpected slowdown in the coarsening process of charge-density waves, challenging conventional understanding of how materials evolve over time.

Suppressed coarsening dynamics are observed in the Holstein chain, driven by diffusive kink motion and reduced defect annihilation in a hybrid quantum-classical system.

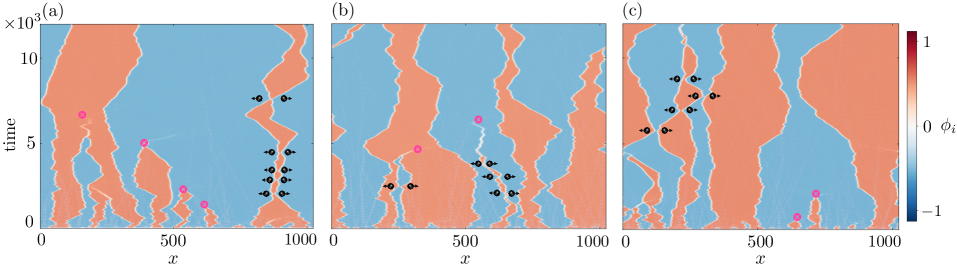

Conventional descriptions of defect dynamics often assume coarsening processes governed by either ballistic annihilation or classical diffusion, yet these fail to capture the nuanced behavior of isolated, hybrid quantum-classical systems. This research, titled ‘Suppressed coarsening after an interaction quench in the Holstein chain’, investigates nonequilibrium dynamics following a sudden change in interaction strength within a semiclassical model exhibiting charge-density-wave order. We demonstrate that such quenches lead to an intermediate regime characterized by suppressed coarsening-anomalous kink dynamics with a scaling exponent of t^{-1/3}-resulting from diffusive kink motion induced by the electronic degrees of freedom acting as an effective internal bath. How do these findings reshape our understanding of defect kinetics and the interplay between quantum coherence and classical dissipation in isolated systems far from equilibrium?

Unveiling Emergent Order: The Dance of Charge Density Waves

Charge-density waves, or CDWs, exemplify a remarkable state of matter where electrons spontaneously organize, creating a periodic modulation of the electron density within a material. This isn’t a simple static arrangement; rather, it emerges from the delicate interplay between the electrons and the atomic lattice itself. Electrons, attempting to minimize their energy, interact with the vibrations of the atoms – the lattice – leading to a distortion of the normally regular atomic structure. This cooperative effect results in a new, lower-energy state characterized by the traveling wave of charge density. The phenomenon isn’t limited to one-dimensional systems, though it is most easily visualized there; it occurs in various materials, and understanding these emergent patterns is vital for tailoring materials with specific electrical and thermal properties. Essentially, the material reorganizes itself at a fundamental level, showcasing a collective behavior not present in its individual components.

The ability to manipulate charge-density waves (CDWs) holds significant promise for tailoring material characteristics. These subtle, periodic modulations of electron density aren’t merely static features; their formation and evolution are dynamic processes directly influencing a material’s conductivity, optical properties, and even its mechanical behavior. Researchers are actively investigating methods to control CDW phases – pinning, sliding, or suppressing their formation – to engineer materials with specific functionalities. For instance, inducing a CDW phase transition can create low-friction surfaces, while controlling CDW motion offers a pathway towards novel electronic devices. Ultimately, a deeper understanding of these dynamics enables the design of materials with properties optimized for applications ranging from energy storage and conversion to advanced sensing technologies.

The conventional theoretical frameworks used to describe charge-density wave (CDW) formation frequently fall short when addressing the intricacies of their dynamic behavior. These materials exhibit collective electronic phenomena occurring across multiple timescales – from the rapid modulation of electron density to the slower, more gradual rearrangements of the atomic lattice. Existing models often treat these processes as either instantaneous or completely decoupled, failing to capture the crucial feedback loops and resonant interactions that govern CDW evolution. This simplification obscures the emergence of complex behaviors, such as CDW pinning, sliding, and phase transitions, limiting the ability to predict and control material properties. A more nuanced understanding, incorporating the interplay between these timescales, is therefore essential for unlocking the full potential of CDW materials in advanced technologies.

Kinks and the Arrest of Domain Growth: The Obstacles to Order

Charge density wave (CDW) dynamics are significantly impacted by the presence of kinks, which are topological defects forming within the CDW structure. These kinks represent localized disruptions in the periodic modulation of the electronic density and function as mobile obstacles to the movement of domain walls. As domain walls attempt to sweep through the material, they encounter these kinks, resulting in scattering and impeding their progress. The density and mobility of these kinks directly influence the rate of domain wall motion and, consequently, the overall kinetics of CDW formation and evolution. This interaction is not simply a physical barrier; the kinks themselves possess momentum and can be excited, further complicating the CDW dynamics and contributing to non-equilibrium behavior.

Domain coarsening, the process by which smaller charge density wave (CDW) domains are absorbed by larger ones, is regulated by the movement of kinks – topological defects within the CDW lattice. Kink motion isn’t solely free propagation; it consists of alternating periods of ballistic travel – unimpeded movement at the Fermi velocity – and elastic scattering events. These scattering events occur when kinks collide with impurities, defects, or other kinks, altering their direction and slowing domain wall velocity. The rate of domain coarsening is therefore directly proportional to the mean free path between scattering events and the kink velocity during ballistic phases; increased scattering frequency or reduced velocity leads to slower coarsening, while longer mean free paths and higher velocities accelerate the process. This interplay defines the time-dependent reduction in domain boundary area and the ultimate stabilization of the CDW structure.

Under specific conditions, the immobilization of kinks within a Charge Density Wave (CDW) lattice results in an arrested CDW state. This occurs when the energy landscape prevents kink motion, effectively pinning these topological defects. Consequently, domain wall propagation is inhibited, preventing further domain coarsening and halting the overall growth of CDW domains. This arrested state represents a unique material configuration characterized by stable, immobile CDW domains and a consequent deviation from typical CDW dynamics; it’s observed when parameters such as temperature or applied electric field reach thresholds that favor kink pinning over propagation.

Simulating Complexity: The Ehrenfest Framework for Non-Adiabatic Dynamics

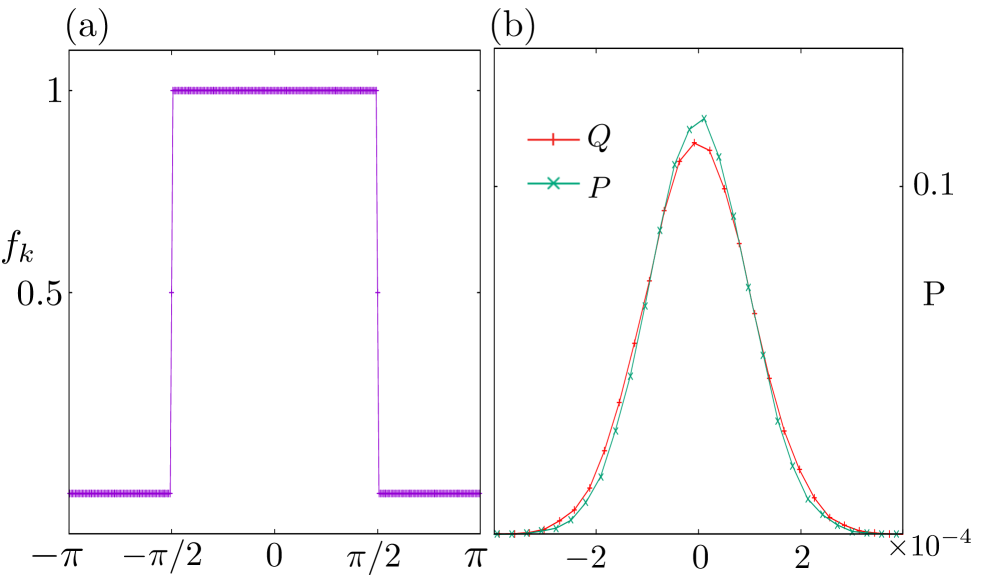

The Ehrenfest nonadiabatic framework simulates the Holstein model by treating electronic and lattice degrees of freedom as coupled but distinct systems. This approach utilizes classical equations of motion for both the electrons and the phonons, incorporating a coupling term that allows for energy transfer between them without assuming a strict adiabatic separation. Specifically, the framework calculates the time evolution of the electronic and lattice variables by iteratively solving equations derived from the Hamiltonian, effectively averaging over nuclear motion to determine the electron dynamics and vice-versa. This allows for the investigation of situations where the Born-Oppenheimer approximation breaks down, particularly when the electronic and nuclear motions are strongly coupled, which is critical for modeling charge density wave (CDW) phenomena and other non-equilibrium dynamics.

Non-dissipative dynamics, within the context of charge density wave (CDW) systems, refer to the coherent evolution of the system without energy loss to external degrees of freedom. This is critical for observing long-lived phenomena such as the sustained oscillation of CDW phases and the propagation of domain walls. Unlike dissipative processes which lead to damping and decay, non-dissipative dynamics allow for the emergence of collective behaviors over extended timescales. Accurate modeling of these dynamics necessitates accounting for the interplay between electronic and lattice motion without introducing artificial damping mechanisms, enabling the simulation of kink propagation, domain growth, and the observation of coherent effects governed by the electron-phonon coupling strength λ.

The nonadiabaticity parameter, denoted as r, is central to accurately modeling charge density wave (CDW) dynamics within the Holstein model. This parameter quantifies the relative strength of the electronic and lattice timescales, directly influencing the evolution of topological defects known as kinks. A higher value of r indicates a stronger coupling between electrons and phonons, leading to more pronounced kink dynamics and a greater impact on CDW domain growth. Specifically, r is directly proportional to the electron-phonon coupling strength λ, which governs the overall strength of the electron-lattice interaction; thus, precise control and consideration of r is essential for simulating and predicting the CDW system’s behavior, including domain wall motion and the emergence of long-lived collective phenomena.

Beyond Equilibrium: Prethermalization and the Slow Dance of Coarsening

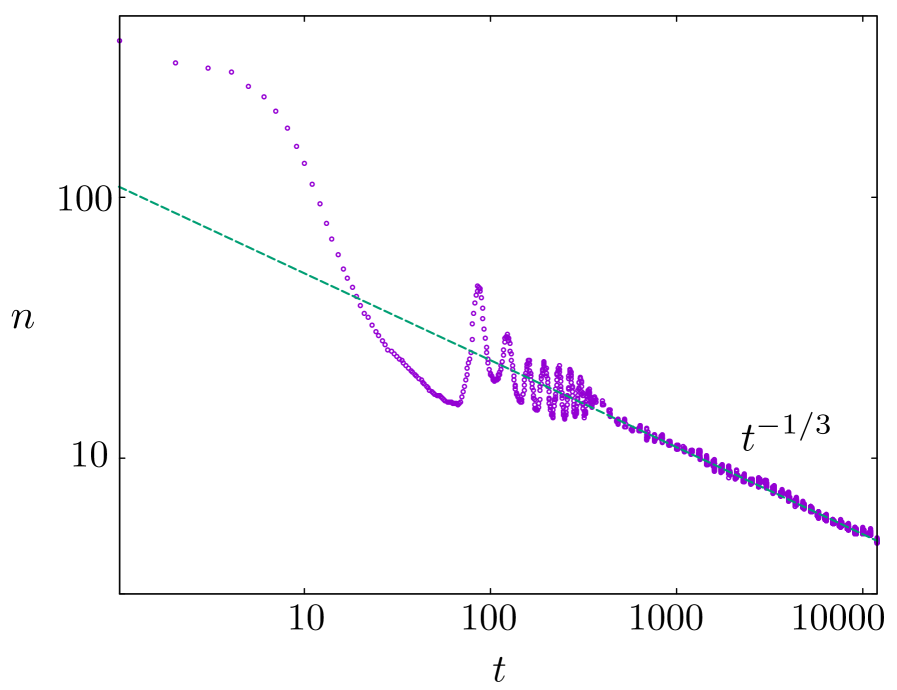

The evolution of topological defects, specifically kinks, within the system doesn’t immediately lead to thermal equilibrium; instead, the dynamics, accurately described by the Ehrenfest framework-a quantum-like approach for classical systems-generate a distinct prethermalized state. This intermediate stage arises because the kink dynamics are largely non-dissipative, meaning energy isn’t rapidly lost to heat, allowing coherent oscillations in the density of these defects to persist for extended periods. Consequently, the system temporarily halts the typical coarsening process-where domains grow and defects diminish-exhibiting behaviors that differ significantly from those predicted by standard diffusive models. This prethermalization acts as a stepping stone, delaying the approach to true equilibrium and revealing a richer, more complex transient behavior before eventual thermalization occurs.

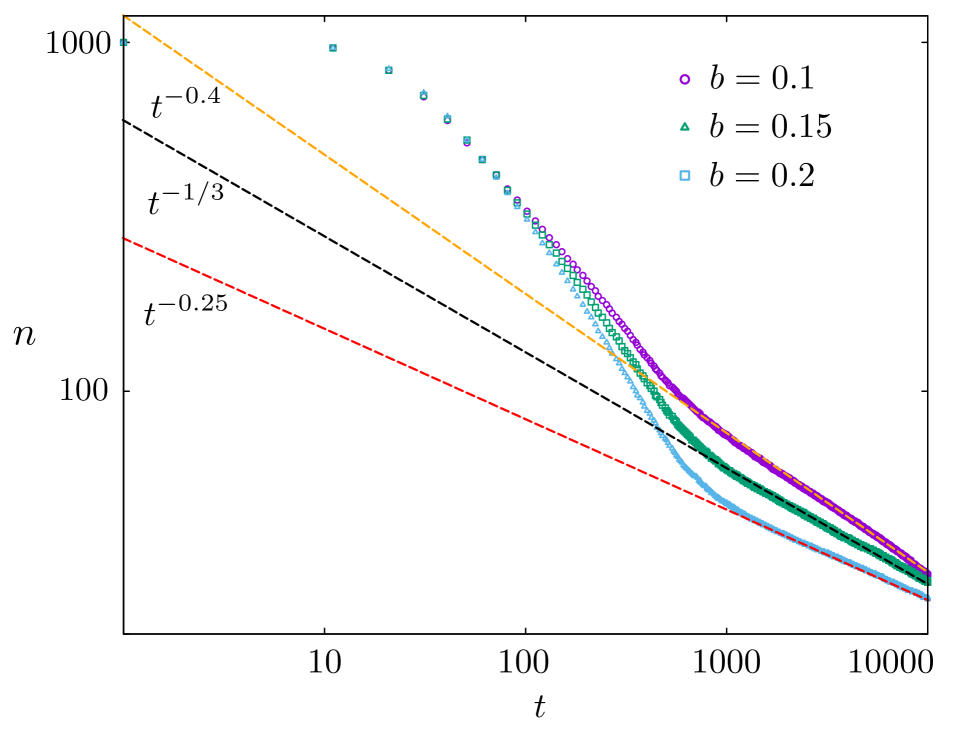

The system’s evolution doesn’t immediately settle into a stable, equilibrium state; instead, it first enters a prethermalized phase marked by persistent, oscillatory behavior in the density of kinks – localized defects separating regions of differing order. This isn’t merely a temporary fluctuation; these oscillations endure for a considerable time, influencing the overall domain growth. Notably, the domains don’t expand at the rate predicted by traditional diffusion-based models. Instead, the characteristic length scale of these domains grows as L(t) \sim t^{1/3}, and the kink density diminishes as n(t) \sim t^{-1/3}. This unconventional algebraic scaling, significantly slower than the expected t^{-1/2} rate, provides strong validation for the theoretical framework describing these non-equilibrium dynamics and highlights a fundamentally different coarsening mechanism at play.

Analysis reveals an unconventional dynamic in domain growth and kink behavior, demonstrating that the characteristic length, representing the typical domain size, scales with time as L(t) \sim t^{1/3}. Simultaneously, the density of kinks – topological defects separating domains – diminishes according to n(t) \sim t^{-1/3}. This observed 1/3 power-law scaling for both domain growth and defect annihilation signifies a markedly slower coarsening process when compared to the standard diffusive behavior characterized by a 1/2 exponent. These findings not only validate the theoretical model employed, but also suggest a fundamentally different mechanism governing the system’s evolution towards equilibrium, highlighting a prolonged period of dynamic rearrangement before reaching a stable state.

The study of coarsening dynamics in the Holstein chain reveals a system resisting simple categorization. It’s a compromise between knowledge of quantum-classical hybrid systems and the convenience of established models. The observed suppression of annihilation-kinks diffusing without readily combining-doesn’t fit neatly into conventional descriptions of defect kinetics. As Paul Feyerabend noted, “Anything goes.” This isn’t a celebration of intellectual chaos, but rather an acknowledgement that clinging to a single, ‘optimal’ framework-even one grounded in solid physics-can obscure genuine phenomena. The researchers didn’t seek to prove a theory, but rather to meticulously document a deviation, highlighting the crucial role of uncertainty in advancing understanding.

Where Do the Errors Lead?

The observed suppression of coarsening isn’t, in itself, surprising. What’s notable is the way it manifests-a slowing dictated not by energetic barriers, but by the kinematics of defect diffusion. The model, while illuminating, remains a simplification. The Holstein chain, even in this hybrid quantum-classical formulation, abstracts away the inevitable disorder of real materials. Future work must address the influence of pinning potentials, not as perturbations, but as integral components of the coarsening landscape. One suspects the true complexity lies not in the presence of defects, but in their correlated errors-the subtle interplay between annihilation events that should occur and those that, for reasons not fully captured by the model, do not.

A critical limitation resides in the Ehrenfest dynamics employed. While computationally convenient, it skirts the fundamental question of quantum decoherence. How robust are these findings against a more rigorous treatment of quantum effects? Does the observed slowing represent a genuine departure from standard coarsening, or merely an artifact of the chosen classical approximation? The answer, predictably, will not be a single number, but a distribution of possibilities-a map of uncertainties.

Ultimately, the value of this work isn’t in confirming existing theories, but in highlighting their failures. It suggests a need to move beyond simple scaling laws and embrace the messy reality of defect kinetics. Wisdom, after all, isn’t about minimizing error, but about accurately quantifying it. The next step isn’t to refine the model, but to design experiments capable of exposing its inherent limitations.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.05815.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- God Of War: Sons Of Sparta – Interactive Map

- Epic Games Store Free Games for November 6 Are Great for the Busy Holiday Season

- How to Unlock & Upgrade Hobbies in Heartopia

- Battlefield 6 Open Beta Anti-Cheat Has Weird Issue on PC

- Someone Made a SNES-Like Version of Super Mario Bros. Wonder, and You Can Play it for Free

- Sony Shuts Down PlayStation Stars Loyalty Program

- EUR USD PREDICTION

- The Mandalorian & Grogu Hits A Worrying Star Wars Snag Ahead Of Its Release

- One Piece Chapter 1175 Preview, Release Date, And What To Expect

- Overwatch is Nerfing One of Its New Heroes From Reign of Talon Season 1

2026-02-08 15:59