Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new signature scheme, Eidolon, leverages the complexity of graph coloring to offer robust security in an era threatened by quantum computing and advanced machine learning.

Eidolon is a practical post-quantum signature scheme based on the k-colorability problem, demonstrating resistance to classical and machine learning attacks for moderate graph sizes.

The looming threat of quantum computing necessitates the development of cryptographic systems resilient to attacks beyond the capabilities of classical algorithms. This is addressed in ‘Eidolon: A Practical Post-Quantum Signature Scheme Based on k-Colorability in the Age of Graph Neural Networks’, which proposes a novel signature scheme grounded in the NP-complete k-colorability problem. The authors demonstrate, through empirical analysis against both classical solvers and custom graph neural networks, that well-constructed instances of this scheme exhibit resistance to cryptanalysis for graphs with n \geq 60. Does this work signal a viable path toward leveraging combinatorial hardness as a foundation for secure post-quantum cryptography, and what refinements are needed to scale these schemes to practical security levels?

The Inevitable Quantum Reckoning

The bedrock of modern digital security, public-key cryptography – encompassing protocols like RSA and Elliptic Curve Cryptography – faces an existential threat from the rapid advancement of quantum computing. These algorithms rely on the mathematical difficulty of certain problems for classical computers, such as factoring large numbers or solving the discrete logarithm problem; however,

The development of quantum-resistant cryptographic schemes centers on identifying mathematical problems that prove exceedingly difficult to solve, even with the immense computational power of a quantum computer. These algorithms aren’t merely resistant to known quantum attacks; they rely on problems considered intractable for any computer, classical or quantum. This pursuit isn’t about increasing computational cost, but about fundamentally shifting to problems where the effort required to break the encryption grows exponentially with the key size – a barrier that transcends mere processing power. Candidate solutions explore areas like lattice-based cryptography, code-based cryptography, and multivariate cryptography, each leveraging distinct mathematical structures to ensure long-term security against evolving computational threats. The underlying principle is to move beyond the vulnerabilities of current systems, such as integer factorization and the discrete logarithm problem, toward problems where no efficient solution is known or anticipated, effectively safeguarding data in a post-quantum world.

The development of quantum-resistant cryptography faces significant hurdles beyond simply identifying mathematically complex problems. While several promising post-quantum algorithms exist, translating these into practical, widely deployable systems proves challenging. Many candidates demand substantially larger key sizes and computational resources compared to current standards like RSA or ECC, impacting bandwidth, storage, and processing speeds – a critical concern for resource-constrained devices or high-throughput applications. Furthermore, ensuring both cryptographic strength and efficient implementation requires careful optimization, often involving trade-offs that necessitate thorough security analysis and performance testing. This balancing act – achieving robust security without sacrificing usability or scalability – remains a central obstacle to the seamless integration of post-quantum cryptography into existing infrastructure and a broad adoption across diverse technological landscapes.

Harnessing the Unsolvability of Graph Coloring

The kk-Colorability Problem, a variation of graph coloring, is a computationally difficult problem belonging to the class of NP-complete problems. This means that any problem in NP can be reduced to kk-Colorability in polynomial time, implying no known polynomial-time algorithm can solve it unless P=NP. In the context of post-quantum cryptography, this intractability is leveraged by constructing cryptographic schemes where the security relies on the difficulty of solving kk-Colorability. Specifically, the problem’s complexity provides a basis for creating one-way functions and trapdoor functions, essential components of modern cryptography, that are believed to be resistant to attacks from both classical and quantum computers. The underlying principle is that breaking the cryptographic scheme would necessitate solving an instance of the kk-Colorability Problem, which is currently considered computationally infeasible.

The computational hardness of the kk-Colorability Problem stems from its NP-completeness, meaning any efficient solution would imply P=NP, a widely believed impossibility. Specifically, determining if a graph can be colored with k colors, where k is a fixed integer greater than two, requires exploring a combinatorial search space that grows exponentially with the number of vertices. This inherent complexity renders both exact solutions and efficient approximation algorithms computationally expensive for even moderately sized graphs. Consequently, cryptographic schemes based on this problem offer a degree of resilience against attacks utilizing quantum computers, as known quantum algorithms, such as Grover’s algorithm and Shor’s algorithm, do not provide a polynomial speedup for NP-complete problems in general.

Direct implementation of the kk-Colorability Problem in cryptographic schemes necessitates meticulous design considerations beyond its inherent computational hardness. Naive constructions can introduce vulnerabilities stemming from predictable problem instances or algorithmic inefficiencies; for example, parameter selection significantly impacts both security and performance. Specifically, the size of the graph, the value of ‘k’, and the method of instance generation must be carefully chosen to prevent attacks exploiting structural weaknesses. Furthermore, practical implementation requires optimization of the underlying graph algorithms to minimize computational overhead and ensure acceptable execution times for key generation, encryption, and decryption processes, especially within resource-constrained environments.

Eidolon: A Signature Scheme Rooted in Complexity

Eidolon is a digital signature scheme designed to resist attacks from both classical and quantum computers. It is predicated on the computational hardness of the k-Colorability problem, a known NP-complete problem, offering a post-quantum security foundation. Specifically, the scheme constructs signatures based on solutions to instances of the k-Colorability problem, where finding a valid coloring is computationally difficult without the secret key. This approach contrasts with schemes relying on integer factorization or elliptic curve discrete logarithms, which are vulnerable to Shor’s algorithm on quantum computers. By grounding its security in a different mathematical problem, Eidolon aims to provide long-term signature security in a post-quantum cryptographic landscape.

Eidolon utilizes Zero-Knowledge Proofs (ZKPs) to demonstrate the validity of a signature without revealing the underlying secret information, specifically the graph coloring used in its construction. The Fiat-Shamir Transform is then applied to these ZKPs, converting the interactive proof system into a non-interactive signature scheme. This transformation involves hashing the challenges issued during the ZKP to create a deterministic signature. The resulting signature consists of commitments to the coloring and a proof of its validity, all derived from the transformed ZKP, enabling verification without requiring interaction with a prover and contributing to the scheme’s compact signature size of approximately 2576 bytes for n=200.

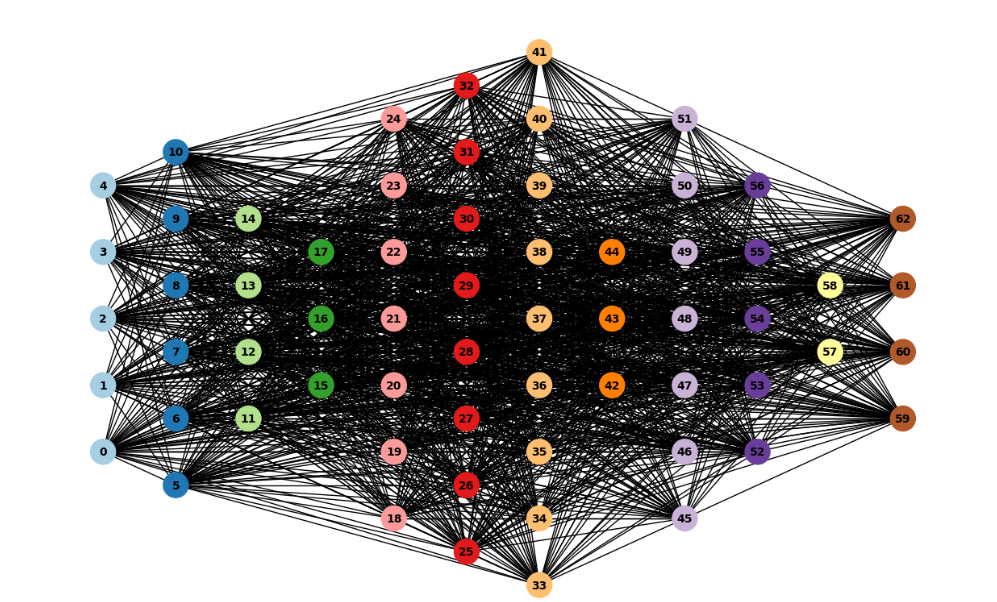

The ‘Quiet Solution’ within the Eidolon signature scheme refers to a specific graph coloring technique used to establish and verify signature integrity. This involves embedding a secret coloring – an assignment of colors to the vertices of a graph – such that the coloring satisfies certain constraints related to the kk-Colorability Problem. The secrecy of this coloring forms the core of the private key. During signature generation, a valid ‘Quiet Solution’ is used to create commitments, and the verifier can confirm the solution’s validity without knowing the coloring itself, relying on zero-knowledge proofs and Merkle tree verification to ensure the commitments correspond to a valid, secretly colored graph.

The Eidolon signature scheme employs Merkle Trees to verify the integrity of commitments made during the signing process, enabling efficient validation without requiring full disclosure of the underlying data. This is achieved by constructing a Merkle Tree from the commitments, allowing a verifier to check the validity of specific commitments through a logarithmic number of hash checks. For a parameter setting of n=200, the resulting signature size is approximately 2576 bytes, reflecting a balance between security and practical usability. This size includes the commitments, the Merkle root, and associated metadata necessary for verification.

The Necessary Foundations: Hiding, Binding, and Formal Proof

The efficacy of cryptographic schemes like Eidolon rests on two fundamental pillars: statistical hiding and computational binding. Statistical hiding ensures that a commitment reveals no information about the underlying value being committed, effectively concealing it from any observer without the unlocking key. This prevents an adversary from predicting the committed value, even with partial knowledge. Simultaneously, computational binding guarantees that once a signer commits to a value, they cannot later alter it – any attempt to do so would require infeasible computational effort. This property is not absolute, but rather relies on the computational hardness of certain problems, preventing forgery and ensuring the integrity of the signed message. Together, these principles establish a secure foundation, allowing parties to confidently engage in cryptographic protocols without fear of information leakage or malicious alteration.

The security guarantees of cryptographic schemes like Eidolon aren’t simply asserted, but are rigorously established through formalization and analysis within the Random Oracle Model (ROM). This model postulates a publicly available function that behaves like a truly random oracle – responding to each unique input with a random output. By proving security relative to this idealized function, cryptographers can confidently assess a scheme’s resistance to attack, even without knowing the exact implementation details of the underlying hash functions. Essentially, the ROM allows for a reductionist approach: if an attacker can break the scheme, that would imply a break in the random oracle itself – an impossibility. This methodology provides a strong, mathematical foundation, shifting the focus from the specific cryptographic primitives to the broader, abstract properties of secure commitment and signature schemes, and bolstering confidence in their practical deployment.

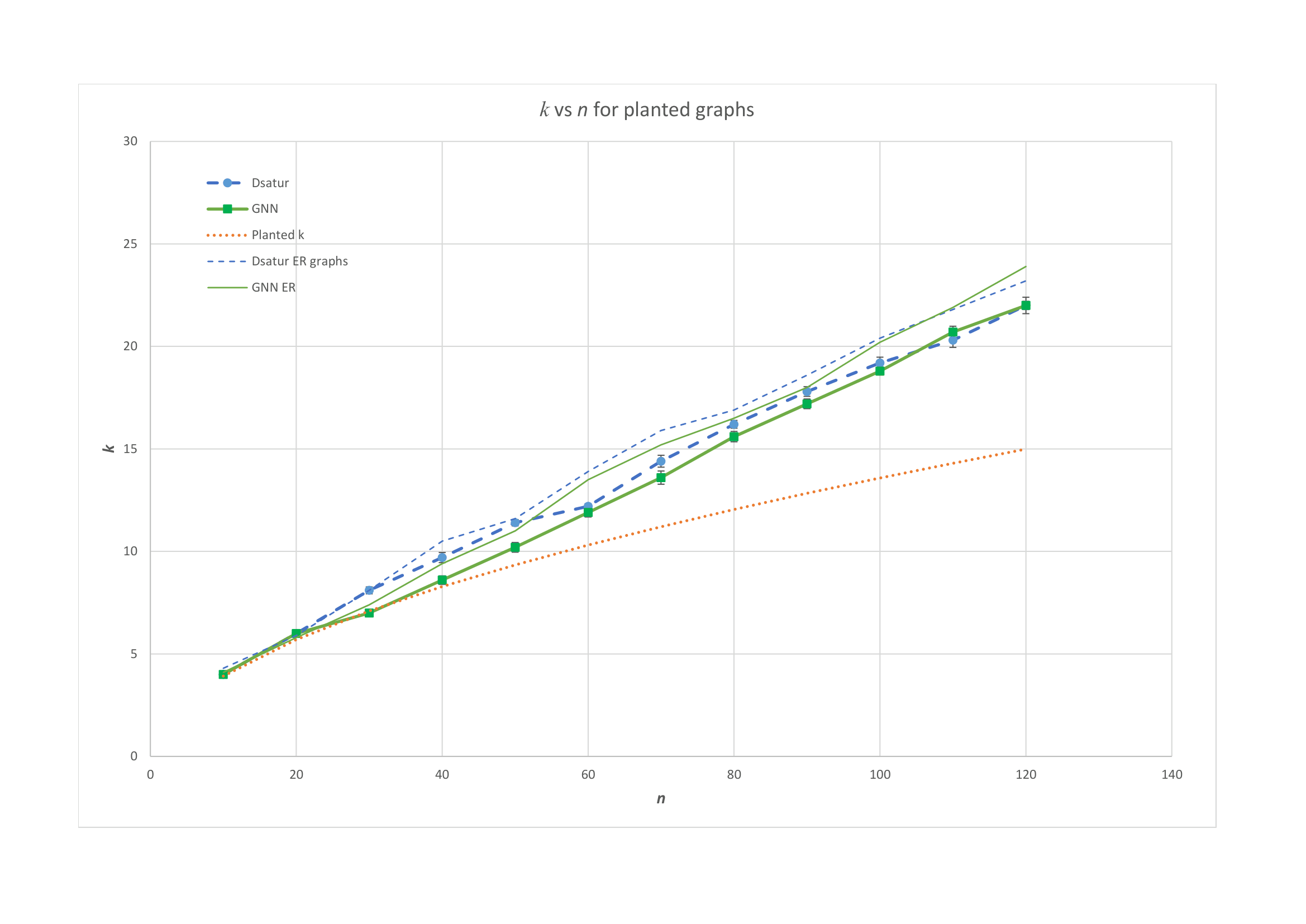

The integrity of digital signatures within Eidolon, and related cryptographic schemes, fundamentally relies on the collision resistance of its Merkle Tree construction; this prevents malicious actors from forging signatures by creating alternative paths to the same commitment. Recent empirical validation rigorously tested the difficulty of breaking this resistance, demonstrating that neither traditional computational solvers nor advanced graph neural networks could successfully recover a ‘planted coloring’ – a known solution embedded within the tree – for graphs containing 60 or more nodes. This finding provides strong evidence that forging signatures becomes computationally infeasible as the size of the Merkle Tree increases, bolstering the overall security of the system and affirming the practical robustness against current and foreseeable attack vectors. The inability of both classical and machine learning approaches to circumvent this security measure underscores the effectiveness of Merkle Trees in maintaining signature authenticity and preventing unauthorized modifications to digital records.

Looking Ahead: Verification, Neural Networks, and Pragmatic Optimization

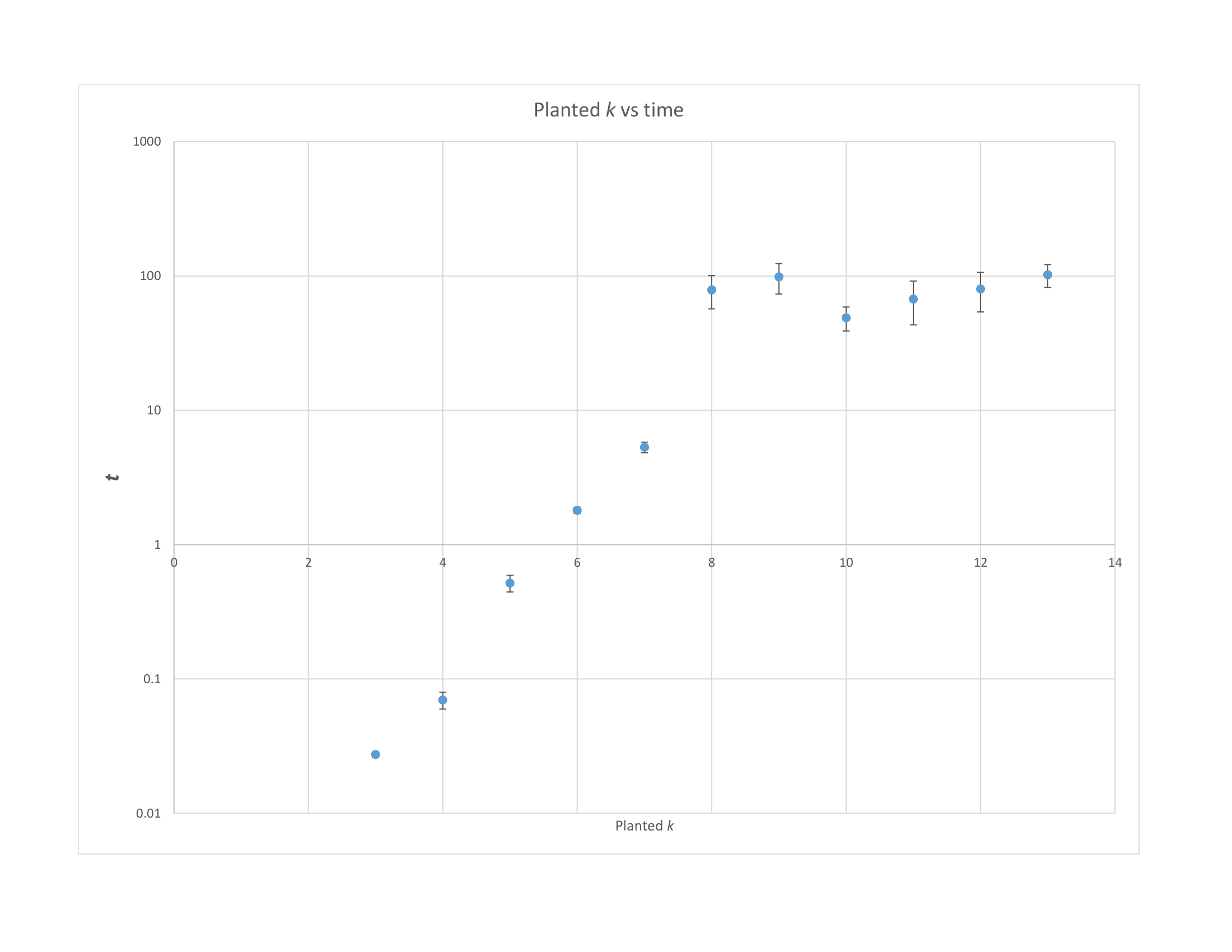

Although Integer Linear Programming (ILP) provides a rigorous method for analyzing the kk-Colorability problem – determining if a graph’s nodes can be colored with kk or fewer colors without adjacent nodes sharing a color – its computational demands quickly become prohibitive as graph size increases. The inherent complexity of ILP means the time required to find a solution grows exponentially with the number of nodes and edges, rendering it impractical for all but the smallest instances. Consequently, researchers are actively pursuing alternative verification methods, such as approximation algorithms and heuristics, that can provide reasonably accurate results in a fraction of the time, even if they lack the absolute certainty of an ILP solution. These methods prioritize scalability, enabling analysis of significantly larger and more complex graphs, despite potentially sacrificing provable optimality.

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) represent a fascinating duality in the context of the kk-Colorability problem. These networks, designed to learn representations of graph structures, demonstrate the potential to efficiently determine whether a graph can be colored with k colors – effectively ‘solving’ the problem for certain instances. However, the same learning capabilities that enable solutions also create a vulnerability; a sufficiently advanced GNN could potentially be ‘attacked’ to discover colorings that bypass established verification methods, suggesting a graph appears colorable when it isn’t. This paradoxical nature – the capacity to both prove and disprove colorability – highlights the need for careful consideration of GNN-based approaches, demanding research into both their robustness and the potential for adversarial manipulation within cryptographic schemes reliant on the kk-Colorability problem.

Continued investigation into cryptographic schemes like Eidolon demands a careful balancing act between several critical factors. While enhanced security is paramount, it cannot come at the expense of computational efficiency or practical implementation. Recent performance evaluations demonstrate that Graph Neural Network algorithms, when applied to graph coloring problems, achieve results comparable to the established DSatur algorithm for graphs exceeding sixty nodes (n>60) . This suggests a viable pathway for scalable solutions, but future work must rigorously analyze the trade-offs inherent in increasing security levels-particularly concerning computational overhead and the complexity of deployment in resource-constrained environments. Optimizing these factors will be crucial for realizing the full potential of Eidolon and similar schemes in real-world applications, ensuring both robust protection and practical feasibility.

The pursuit of cryptographic novelty feels… cyclical. This paper details Eidolon, a scheme built on the kk-colorability problem, hoping to withstand post-quantum threats. It’s a valiant effort, leveraging graph neural networks to enhance security, but one can’t help but observe a pattern. Every supposedly unbreakable system eventually yields to attack, whether through brute force, clever mathematics, or, as this research anticipates, machine learning. As Edsger W. Dijkstra observed, “It’s always possible to commit suicide with a paperclip.” The elegance of a theoretically sound system is often undone by the messy reality of implementation and the relentless ingenuity of those attempting to break it. Production, as always, will have the final say, revealing whether this particular ‘revolutionary’ approach merely adds to the ever-growing pile of tech debt.

What’s Next?

The elegance of framing signature security around graph coloring is… quaint. It evokes memories of simpler times, when a bash script could solve a problem before it ballooned into a distributed system. Of course, ‘moderate graph sizes’ are the operative words. Someone will inevitably attempt to scale this, and then the fun begins. They’ll call it AI and raise funding to ‘optimize’ the coloring process, conveniently ignoring the fundamental hardness assumptions. The documentation will lie again, promising performance that never materializes.

The reliance on zero-knowledge proofs and Merkle trees feels… familiar. Every ‘revolutionary’ scheme eventually reduces to building another layer on top of existing cryptographic primitives. The true challenge isn’t proving security in a lab; it’s surviving the entropy of production. Someone will discover a subtle side-channel leak, or a new attack vector on the graph construction itself. It’s not a matter of if, but when.

Perhaps the most interesting direction lies in exploring the interplay between the kk-colorability problem and the evolving landscape of Graph Neural Networks. Is it possible to leverage GNNs not to break the scheme, but to construct more efficient and provably secure instances? Or will we simply discover that GNNs are just another tool for accelerating the inevitable descent into tech debt-emotional debt with commits, really?

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.02689.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Poppy Playtime Chapter 5: Engineering Workshop Locker Keypad Code Guide

- God Of War: Sons Of Sparta – Interactive Map

- Jujutsu Kaisen Modulo Chapter 23 Preview: Yuji And Maru End Cursed Spirits

- Poppy Playtime 5: Battery Locations & Locker Code for Huggy Escape Room

- Who Is the Information Broker in The Sims 4?

- Poppy Playtime Chapter 5: Emoji Keypad Code in Conditioning

- Why Aave is Making Waves with $1B in Tokenized Assets – You Won’t Believe This!

- Pressure Hand Locker Code in Poppy Playtime: Chapter 5

- How to Unlock all Substories in Yakuza Kiwami 3

- All 100 Substory Locations in Yakuza 0 Director’s Cut

2026-02-04 07:50