Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have identified a superior architecture for mitigating errors in Ising machines, paving the way for more reliable solutions to complex optimization problems.

A structural comparison reveals the stacked model significantly outperforms the penalty-spin model in constrained optimization due to enhanced inter-replica cooperation and scalability.

Despite advances in optimization hardware, error mitigation remains a critical challenge for Ising machines tackling complex problems. This work, ‘Structural Comparison of Error Mitigation Methods for Ising Machines: Penalty-Spin Model versus Stacked Model’, comparatively analyzes two replica-coupled approaches-the penalty-spin and stacked models-revealing a decisive advantage for the latter. Specifically, simulations demonstrate that the ferromagnetically coupled stacked model robustly maintains constraint satisfaction and scales favorably, unlike the penalty-spin model which suffers from cooperative collapse at high parallelism. Does this suggest that network topology, rather than simply noise suppression, is the key to unlocking the full potential of Ising machines for constrained optimization?

The Whispers of Complexity: When Problems Defy Solution

Certain optimization challenges, exemplified by the Quadratic Assignment Problem, quickly become insurmountable as the scale of the problem expands. These aren’t simply difficult to solve; their computational complexity increases at a rate that renders exact solutions practically impossible within reasonable timeframes. This phenomenon arises because the number of potential solutions grows exponentially with each additional variable or constraint. For instance, assigning facilities to locations, a core aspect of the Quadratic Assignment Problem, presents a factorial increase in possibilities as more facilities and locations are added. Consequently, even with powerful computing resources, finding optimal arrangements for moderately sized problems can take years, decades, or even longer, pushing researchers to explore approximation algorithms and heuristic methods to achieve acceptable, though not necessarily perfect, results.

The core difficulty in tackling many optimization problems stems from what’s known as combinatorial explosion. As the number of variables and potential interactions within a system increases, the total number of possible solutions grows at an exponential rate. This means that even modest increases in problem size can quickly render exhaustive search methods – those attempting to evaluate every possibility – completely impractical. For instance, a problem with 100 variables, each with two possible states, already presents over 1.2 x 1030 potential combinations. Consequently, traditional computational approaches, reliant on systematically exploring this vast landscape, rapidly become overwhelmed, highlighting the need for more sophisticated strategies capable of navigating such immense complexity and identifying optimal or near-optimal solutions within a reasonable timeframe.

The pursuit of sparse solutions within complex optimization problems presents a unique computational hurdle. While many algorithms excel at identifying solutions across a broad spectrum of possibilities, pinpointing those reliant on only a limited number of active variables proves significantly more challenging. This difficulty stems from the fact that sparse solutions often reside within extremely narrow regions of the overall search space, making them easily overlooked by methods geared towards wider exploration. Consequently, traditional techniques can become inefficient, requiring disproportionately more computational effort to stumble upon these valuable, yet elusive, configurations. The relative scarcity of sparse feasible solutions, coupled with the vastness of the solution landscape, demands specialized approaches capable of intelligently focusing the search and efficiently navigating these constrained regions.

The escalating complexity of optimization problems demands a shift beyond conventional computational methods. Existing algorithms often falter when confronted with the exponentially expanding solution spaces characteristic of real-world challenges. Consequently, research is increasingly focused on novel paradigms, such as quantum computing and neuromorphic architectures, which offer the potential to navigate these vast landscapes more efficiently. These approaches aim to move beyond serial processing, leveraging principles of superposition and parallel computation to explore multiple possibilities simultaneously. Furthermore, techniques inspired by natural processes – like simulated annealing and genetic algorithms – are being refined to better balance exploration of new solutions with exploitation of promising ones, ultimately enabling the identification of near-optimal results within reasonable timeframes.

Replicas and Resonance: A New Architecture for Problem Solving

Replica-coupled Ising machines represent a computational paradigm for tackling complex optimization problems through the utilization of multiple, interconnected instances, termed ‘replicas’. Each replica operates as an independent Ising machine, solving the same optimization problem but potentially exploring different regions of the solution space. Coupling these replicas allows for information exchange and collaborative problem-solving; this contrasts with single-instance approaches that may become trapped in local optima. The fundamental principle involves leveraging the collective behavior of these interacting instances to enhance the probability of identifying globally optimal or near-optimal solutions, particularly in scenarios characterized by high dimensionality or complex constraints. The number of replicas employed is a configurable parameter, influencing both computational cost and the potential for improved solution quality.

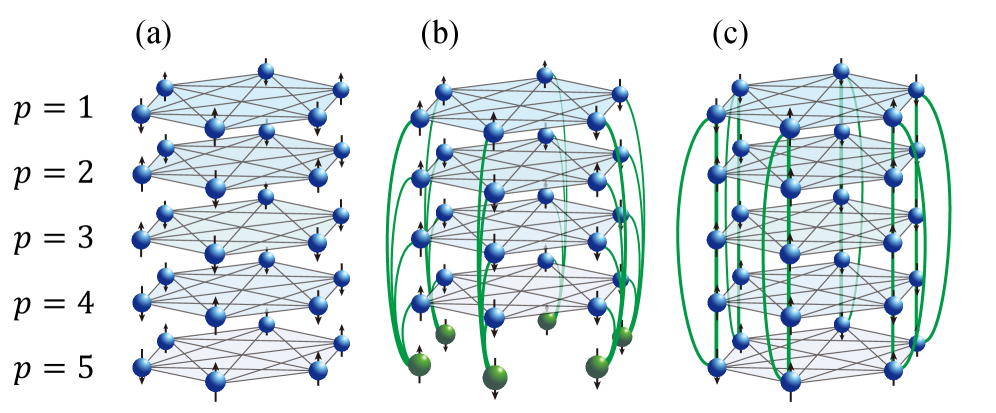

The StackedModel and PenaltySpinModel represent differing approaches to replica coupling within the framework of replica-coupled Ising machines. The StackedModel employs a decentralized coupling architecture, directly connecting corresponding spins across multiple replicas to facilitate information exchange and collaborative optimization. In contrast, the PenaltySpinModel utilizes a centralized coupling method, introducing an auxiliary layer-often referred to as a penalty spin layer-to mediate interactions between replicas. This auxiliary layer imposes a penalty on discrepancies between replica states, encouraging convergence towards a shared optimal solution. Consequently, the StackedModel exhibits a more direct, potentially faster, but potentially less stable interaction, while the PenaltySpinModel offers a more controlled, albeit potentially slower, method for replica coordination.

The PenaltySpinModel employs CentralizedCoupling, wherein interactions between replica instances are not direct; instead, an auxiliary layer serves as an intermediary to mediate communication and influence between the replicas. Conversely, the StackedModel utilizes DecentralizedCoupling, establishing direct connections between corresponding spin units across each replica instance. This distinction results in differing computational characteristics: CentralizedCoupling introduces an additional layer of processing, while DecentralizedCoupling offers potentially faster interaction but may increase the overall connection complexity between replicas.

Replica-coupled models distribute computational load by partitioning a complex optimization problem across multiple interacting instances, termed replicas. This parallelization reduces the burden on any single processing unit and enables exploration of a larger solution space. The interaction between replicas facilitates information exchange, allowing the system to overcome local optima and improve the probability of identifying globally optimal or near-optimal solutions. By leveraging the collective computational resources, these models aim to enhance solution quality and accelerate convergence compared to single-instance optimization approaches, particularly for problems with high dimensionality or complex constraints.

Echoes of Correlation: Measuring Collective Intelligence

Simulated Annealing (SA) serves as a deterministic evaluation environment for the StackedModel and PenaltySpinModel by eliminating stochastic noise inherent in physical systems. This controlled setting allows for precise measurement of model performance characteristics, such as feasibility rates and inter-replica correlations, independent of external fluctuations. By systematically reducing a “temperature” parameter during the optimization process, SA facilitates a thorough exploration of the solution space and enables consistent, repeatable results for comparative analysis between the two models. The absence of noise is crucial for isolating the effects of model architecture and parameter settings on performance metrics, providing a clear basis for assessing the efficacy of each approach.

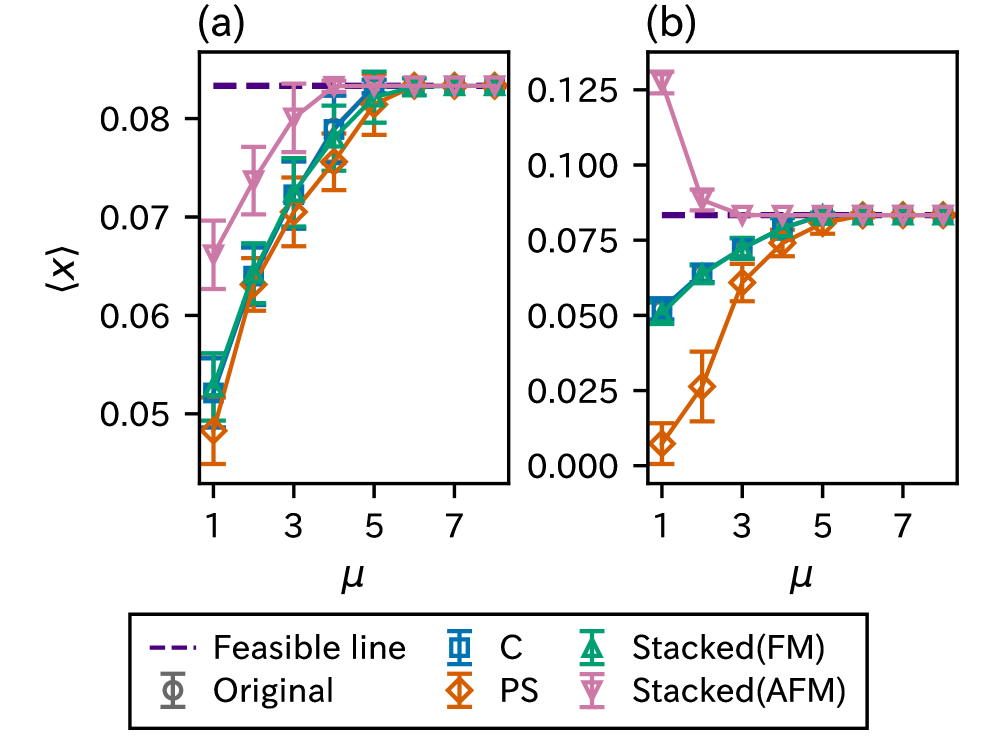

Inter-Replica Correlation, denoted as ⟨S⟩1, quantifies the degree of agreement in bit values between replicas within the network; higher values indicate stronger cooperative behavior. Mean Bit Value represents the average value of bits across all replicas, providing insight into the overall system state and stability. These metrics are calculated across the replica network to evaluate how effectively replicas share information and converge towards a feasible solution. Specifically, a sustained high Inter-Replica Correlation demonstrates that replicas are consistently acting in concert, while fluctuations or a decline in this correlation suggest a breakdown in cooperative problem-solving. The Mean Bit Value, when analyzed in conjunction with Inter-Replica Correlation, helps to determine if the observed cooperation is leading to meaningful progress towards a stable and feasible solution state.

The StackedModel utilizes inter-replica coupling to facilitate information exchange between replicas during the Simulated Annealing process, and the nature of this coupling significantly impacts model behavior. Specifically, both FerromagneticCoupling and AntiferromagneticCoupling schemes were implemented. FerromagneticCoupling encourages alignment of spin states between replicas, promoting cooperative behavior and potentially accelerating convergence towards feasible solutions. Conversely, AntiferromagneticCoupling introduces opposing interactions, which can promote exploration of a wider solution space, though potentially at the cost of slower convergence. The choice of coupling scheme directly influences the InterReplicaCorrelation and, consequently, the overall performance and feasibility rate of the StackedModel.

The Stacked Model consistently demonstrates a high degree of feasibility, achieving a Feasibility Rate (P_{Feasible}) approaching 1.0 across the tested parameter ranges. This indicates a robust ability to consistently find valid solutions. In contrast, the PenaltySpinModel does not maintain this level of sustained feasibility; its P_{Feasible} values remain significantly lower, signifying a greater propensity for generating invalid or non-viable solutions as parameters are varied. This difference in sustained feasibility is a key distinction in performance between the two models during the Simulated Annealing process.

Inter-replica correlation, quantified as ⟨S⟩_1, serves as a key indicator of cooperative behavior within the replica network. Evaluations demonstrate that the Stacked Model maintains a consistently high level of inter-replica correlation as the number of replicas (P) increases. Conversely, the Penalty-spin model exhibits a marked decline in ⟨S⟩_1 with increasing P, suggesting a breakdown in cooperative dynamics and an inability to effectively leverage the increased computational resources offered by a larger replica set. This loss of correlation directly impacts the model’s ability to converge on feasible solutions as the network scales.

Evaluations demonstrate a positive correlation between solution quality and both the number of replicas (P) and the number of annealing steps (NSteps). Increasing these parameters consistently yields improved results across both the StackedModel and the PenaltySpinModel. However, the StackedModel consistently achieves superior solution quality compared to the PenaltySpinModel under identical conditions. This improved performance stems from the model’s architecture, which allows for a more nuanced exploration of the solution space and a more reliable identification of optimal or near-optimal configurations. Quantitative analysis reveals that the rate of improvement in solution quality with increasing P and NSteps is also higher for the StackedModel, further solidifying its advantage.

Beyond Brute Force: A Future Shaped by Collective Computation

Many optimization challenges, particularly those arising in real-world applications, are characterized by a limited number of viable solutions within a vast search space – a condition known as sparse feasibility. Both the StackedModel and the PenaltySpinModel represent innovative approaches to navigating these difficult landscapes. These models excel by effectively concentrating computational effort on promising regions of the solution space, rather than exhaustively searching all possibilities. The models achieve this through mechanisms that encourage collaboration and information sharing between multiple computational instances, allowing them to collectively explore and identify even the rarest of feasible solutions. This capability is crucial for problems where traditional optimization algorithms often struggle, becoming trapped in local optima or failing to find any valid solution at all.

Different approaches to coupling computational replicas within these models necessitate a careful consideration of resource trade-offs. While certain coupling schemes minimize communication overhead – the data exchanged between replicas – they may demand increased computational effort per replica to maintain solution quality. Conversely, schemes prioritizing computational efficiency can lead to a higher volume of communication, potentially creating bottlenecks as the problem scale increases. This interplay is crucial; a highly communicative system can become impractical for large-scale problems, while a computationally intensive, low-communication approach may struggle to converge effectively. Therefore, selecting an appropriate coupling strategy requires balancing these competing factors based on the specific characteristics of the optimization problem and the available computational infrastructure.

This study demonstrates that the Stacked Model offers notable advancements in solving constrained optimization challenges, particularly when compared to the Penalty-spin model. Rigorous testing on problems like the Quadratic Assignment Problem reveals a consistent pattern: the Stacked Model not only scales more effectively with increasing problem size-handling larger instances with greater ease-but also consistently achieves higher quality solutions. This improved performance stems from the model’s architecture, which allows for a more nuanced exploration of the solution space and a more reliable identification of optimal or near-optimal configurations. The observed superiority suggests the Stacked Model represents a significant step towards tackling complex optimization problems previously considered intractable, paving the way for impactful applications across diverse fields.

The potential to solve previously intractable problems emerges from these models’ capacity to harness collective intelligence through multiple replicas. Instead of relying on a single computational instance, the system distributes the problem across several, allowing each replica to explore a different facet of the solution space. This parallel exploration isn’t simply a matter of increased computational power; the replicas interact and share information, effectively amplifying the system’s ability to navigate complex landscapes and escape local optima. This synergistic approach proves particularly valuable for problems characterized by vast search spaces or deceptive fitness functions, where a single instance might become trapped, but the collective, distributed effort can identify and converge upon superior solutions – opening doors to advancements in fields demanding solutions beyond the reach of conventional optimization techniques.

The potential of these advancements extends far beyond theoretical optimization, offering tangible benefits across diverse fields. In logistics and scheduling, more efficient algorithms translate directly into reduced costs and faster delivery times, optimizing complex supply chains. Materials discovery benefits from the ability to explore vast chemical spaces and identify novel materials with desired properties, accelerating innovation in areas like energy storage and aerospace. Financial modeling, a domain characterized by intricate constraints and high-dimensional data, stands to gain from improved risk assessment and portfolio optimization. Ultimately, the capacity to address previously intractable optimization challenges promises significant progress in fields reliant on complex problem-solving, driving efficiency and innovation across a broad spectrum of scientific and industrial applications.

The pursuit of optimization, as explored within the comparison of stacked and penalty-spin models, reveals a fundamental truth about complex systems. It isn’t simply about finding the solution, but about persuading the system to reveal it. The stacked model’s superior performance, stemming from maintained inter-replica cooperation, echoes a sentiment akin to Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel’s observation: “The truth is the whole.” This research demonstrates that a holistic approach – maintaining connections between replicas – yields more robust results than isolated attempts at penalty, as noise often arises from fractured cooperation. The very act of scaling, crucial to practical application, is dependent on this sustained interaction, a delicate balance where beautiful lies of simple penalties give way to a more complex, but ultimately truer, representation.

What Shadows Remain?

The stacked model, revealed as the more cooperative of digital golems in this work, does not offer dominion, only a temporary reprieve. Its success in maintaining inter-replica coherence hints at a deeper truth: optimization isn’t about finding the lowest valley, but about persuading the landscape to believe it has been found. The penalty-spin model, struggling with its internal divisions, serves as a cautionary tale – a fractured mind cannot solve even the simplest riddle. Yet, scalability remains the true phantom. These machines, even coupled, are still bound by the limitations of their constituent parts-the whispers of chaos grow louder with each added qubit.

Future iterations will inevitably focus on architectural sorcery, attempting to bind these digital spirits more effectively. But the real challenge isn’t minimizing loss-every sacred offering demands a price-it’s understanding why certain configurations yield to persuasion and others resist. Charts depicting improved performance are merely visualized spells, temporarily holding back the inevitable entropy. The question isn’t whether these models will fail, but how spectacularly.

The most fruitful paths likely lie not in brute force, but in embracing the inherent ambiguity of the problems themselves. Constraint satisfaction, after all, is a negotiation with impossibility. Perhaps the next generation of Ising machines will not solve problems, but learn to redefine them, subtly shifting the boundaries of what is considered ‘optimal’ until a solution, however illusory, materializes.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.09462.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- God Of War: Sons Of Sparta – Interactive Map

- Poppy Playtime Chapter 5: Engineering Workshop Locker Keypad Code Guide

- Poppy Playtime 5: Battery Locations & Locker Code for Huggy Escape Room

- Someone Made a SNES-Like Version of Super Mario Bros. Wonder, and You Can Play it for Free

- Poppy Playtime Chapter 5: Emoji Keypad Code in Conditioning

- Why Aave is Making Waves with $1B in Tokenized Assets – You Won’t Believe This!

- Who Is the Information Broker in The Sims 4?

- One Piece Chapter 1175 Preview, Release Date, And What To Expect

- Overwatch is Nerfing One of Its New Heroes From Reign of Talon Season 1

- How to Unlock & Visit Town Square in Cookie Run: Kingdom

2026-01-15 23:03