Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals that the Kondo effect, a hallmark of quantum impurity problems, can persist in one-dimensional systems even with strong scattering, thanks to the crucial role of environmental correlations.

This study demonstrates the survival of the Kondo effect in ytterbium atom chains with repulsive spin impurities, identifying the conditions for suppressed Kondo temperatures in a correlated fermionic environment.

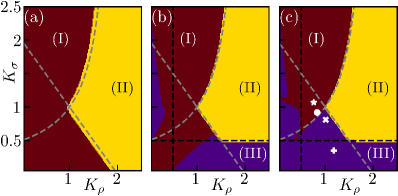

The robust Kondo effect, a cornerstone of strongly-correlated physics, is typically challenged by competing scattering mechanisms within a fermionic environment. This is the central question addressed in ‘Pathway to Kondo physics in ytterbium atom chains with repulsive spin impurities’, which investigates the fate of Kondo physics in one-dimensional ytterbium atom chains subject to both magnetic and potential scattering. Our work demonstrates that, despite strong potential scattering that can quench impurity entanglement, Kondo screening persists under specific conditions dictated by environmental correlations. These findings establish a quantitative criterion for realizing Kondo screening in cold-atom platforms-but how might these insights be extended to explore more complex Kondo lattice systems?

The Quantum Dance of Resistance: Unveiling the Kondo Effect

The Kondo effect manifests as a peculiar phenomenon in metallic systems: at sufficiently low temperatures, the electrical resistance, rather than continuing to decrease as expected, reaches a minimum and then begins to increase. This counterintuitive behavior arises from the scattering of conduction electrons by localized magnetic impurities within the metal. These impurities possess unpaired electron spins that interact with the spins of the conducting electrons. While one might anticipate increased scattering and thus resistance, the interaction leads to a many-body effect where the conduction electrons effectively ‘screen’ the impurity’s magnetic moment, forming a composite, non-magnetic state. This screening reduces the scattering at very low temperatures, initially decreasing resistance, but the formation of this composite state also introduces a new scattering mechanism that ultimately dominates, causing the resistance to rise – a signature of the Kondo effect and a testament to the intricate interplay of quantum mechanics and material properties.

The Kondo effect isn’t simply a matter of individual electrons bouncing off a magnetic atom; it arises from a deeply interconnected dance of many electrons. Each conduction electron’s behavior is subtly altered by its interactions with both the magnetic impurity and all the other surrounding electrons. This creates a ‘many-body’ problem where predicting the system’s overall behavior demands tracking the correlations between countless particles – a task that quickly becomes computationally intractable as the number of electrons increases. Unlike simpler scenarios, the collective behavior isn’t merely the sum of individual interactions; emergent properties arise from these complex correlations, requiring sophisticated theoretical tools to untangle the interplay and accurately model the resulting decrease in electrical resistance at low temperatures.

The Kondo effect presents a formidable challenge to conventional solid-state physics because the strong correlations between conduction electrons and localized magnetic impurities invalidate the assumptions of standard perturbation theory. This theoretical framework, typically successful in approximating many physical systems, relies on treating interactions as small disturbances, an approach that fails when the coupling between electrons and the impurity is significant. The interactions aren’t merely additive; instead, they create collective behavior where the impurity’s magnetic moment becomes screened by the surrounding electrons, forming a many-body entangled state. Consequently, physicists have turned to alternative, non-perturbative methods – such as the renormalization group and bosonization techniques – to accurately describe the system’s behavior and the surprising decrease in electrical resistance observed at low temperatures, a phenomenon inexplicable within the confines of traditional approximations.

Beyond the Fermi Liquid: The Emergence of Luttinger Liquids

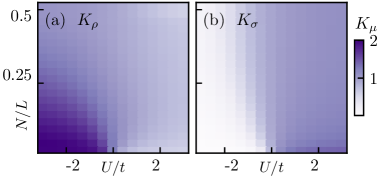

Luttinger liquids differ fundamentally from the more commonly observed Fermi liquids in their excitation spectra and correlation functions. While Fermi liquids are characterized by quasiparticle excitations with a well-defined momentum and energy, and exhibit power-law decay of correlations with exponents determined by the dimensionality of the system, Luttinger liquids exhibit collective excitations that are not necessarily associated with individual electrons. Specifically, the correlation functions in a Luttinger liquid decay with a power law, but the exponent is determined by the Luttinger parameter, K, which can differ significantly from the predictions for Fermi liquids. This leads to behaviors such as spin-charge separation and a breakdown of the single-particle picture typically used to describe metallic systems. The resulting low-energy physics is governed by bosonic excitations rather than fermionic quasiparticles, and the system’s properties are sensitive to interactions between electrons.

The Fermi-Hubbard model, defined by a kinetic energy term for electron hopping and an on-site Coulomb repulsion U, serves as a foundational model for understanding strongly correlated electron systems. In its simplest form, it describes electrons moving on a lattice where each site can be occupied by at most one electron. Luttinger liquid behavior emerges in one-dimensional systems, or quasi-one-dimensional systems, when the repulsive interaction U dominates the kinetic energy, leading to a suppression of charge fluctuations and the formation of collective spin-charge separated excitations. Specifically, when the electron density is tuned such that the chemical potential lies within the Hubbard band, the system transitions from a Mott insulator to a correlated metal exhibiting characteristics of a Luttinger liquid, deviating from the predictions of Fermi liquid theory.

Numerical simulations are essential for confirming the existence of Luttinger liquid phases due to the analytical challenges in solving strongly correlated electron systems. The Density Matrix Renormalization Group (DMRG) is a particularly effective numerical method for one-dimensional systems, allowing for the calculation of ground state properties and dynamic correlations with high accuracy. DMRG directly addresses the many-body Schrödinger equation by efficiently representing the wavefunction as a matrix product state, enabling the study of system sizes and correlation lengths relevant to Luttinger liquid behavior. Validation of theoretical predictions, such as the power-law decay of correlation functions and the spin-charge separation, relies heavily on comparing DMRG results to analytical expectations and experimental observations. These simulations provide crucial evidence for identifying Luttinger liquids in both theoretical models, like the Fermi-Hubbard model in the limit of strong interactions, and in real materials exhibiting quasi-one-dimensional characteristics.

Simplifying Complexity: Constructing Effective Hamiltonians

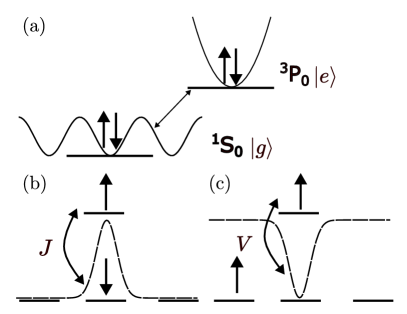

The construction of an effective Hamiltonian for the Kondo effect simplifies analysis by systematically eliminating high-energy degrees of freedom and focusing on the low-energy, strongly interacting states. This is achieved through a Schrieffer-Wolff transformation, which generates an equivalent Hamiltonian that retains only the relevant interactions responsible for the Kondo resonance and scattering. The resulting effective Hamiltonian typically includes a coupling term between the localized magnetic impurity spin \mathbf{S} and the conduction electron spins, along with an exchange interaction parameter J quantifying the strength of this coupling. By concentrating on this reduced set of interactions, the effective Hamiltonian allows for a tractable description of the many-body problem without explicitly treating the full complexity of the conduction band.

Two-particle hole scattering, arising from the interaction between the localized magnetic moment and conduction electrons, is a crucial component in constructing the effective Hamiltonian for the Kondo effect. This process describes the scattering of an electron with momentum k into a state with momentum k', accompanied by a simultaneous flip of the localized spin. The resulting scattering amplitude incorporates information about the exchange interaction and the density of states of the conduction electrons. By explicitly including these scattering processes within the effective Hamiltonian, one can systematically account for the many-body correlations that emerge from the repeated scattering of conduction electrons off the magnetic impurity, going beyond single-particle approximations and accurately representing the low-energy physics of the system.

Renormalization Group (RG) analysis, when applied to the effective Hamiltonian describing the Kondo effect, systematically tracks the evolution of interaction parameters with varying energy scales. This process involves integrating out high-energy degrees of freedom and rescaling the remaining low-energy parameters, revealing how these parameters “flow” as the energy scale is lowered. Identifying fixed points of this flow – parameter values that remain unchanged under rescaling – is crucial, as these correspond to the stable, low-energy behavior of the system. The RG procedure allows determination of critical exponents and universal properties, independent of microscopic details, and provides insight into the system’s behavior near these fixed points, characterizing the different phases of the Kondo effect – for example, the free moment phase or the screened Kondo phase – based on the stability of the fixed points and the direction of the parameter flow.

The Fragility of Correlation: Impurities and the Kondo Temperature

The delicate Kondo effect, a manifestation of strong correlations between conduction electrons and localized magnetic impurities, is surprisingly vulnerable to the presence of even non-magnetic imperfections within a material. These impurities introduce potential scattering, disrupting the formation of the Kondo singlet state and consequently lowering the characteristic Kondo temperature – a critical parameter defining the energy scale below which many-body correlations dominate. This reduction isn’t merely a quantitative shift; it signifies a weakening of the effective interaction between the conduction electrons and the magnetic impurity, altering the system’s low-temperature electronic behavior. The strength of this disruption is directly related to the concentration and scattering potential of the non-magnetic impurities, demonstrating that even seemingly inert components can profoundly impact the emergence of complex quantum phenomena.

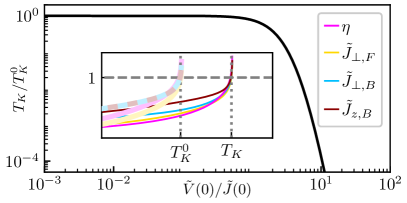

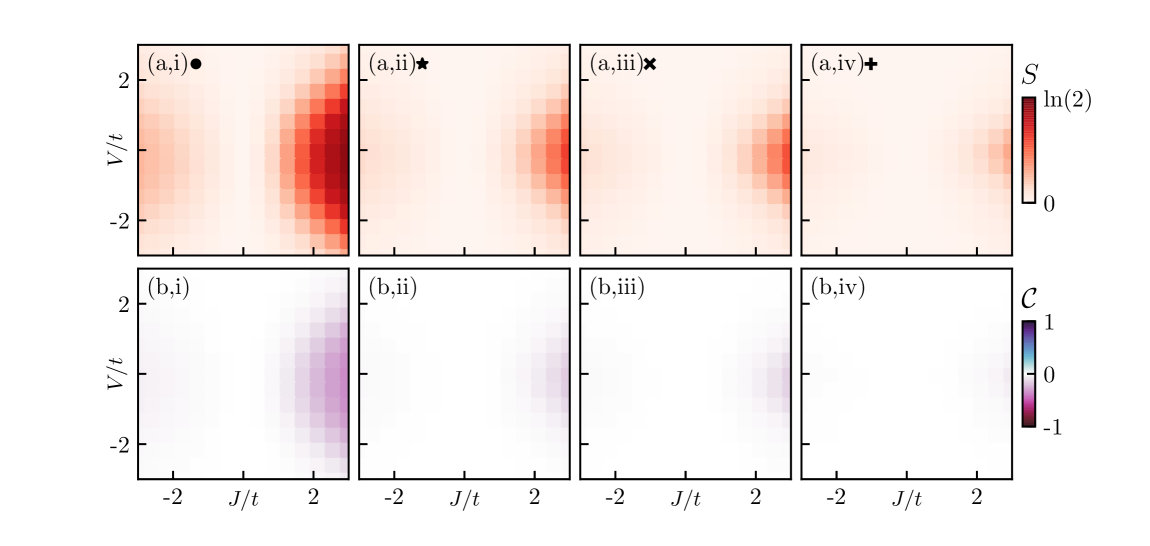

A diminished Kondo temperature indicates a substantial weakening of the intricate many-body correlations within the material, fundamentally changing its behavior at low temperatures. This reduction isn’t merely qualitative; it’s quantifiable, decreasing by a factor of exp(-\pi V^2 / Jv_F). Here, V represents the strength of potential scattering caused by impurities, while J defines the exchange interaction fostering the Kondo effect, and v_F denotes the Fermi velocity of the conducting electrons. Consequently, even relatively small amounts of impurity-induced scattering can significantly suppress the Kondo effect, shifting the system away from a strongly correlated state and towards a simpler, less interactive regime at cryogenic temperatures.

Analyzing the intricate interplay between potential scattering and the Kondo effect often requires computationally demanding methods. However, Poor Man’s Scaling presents a valuable, simplified approach to understanding this relationship quantitatively. This technique, while foregoing some of the precision of more complex calculations, allows researchers to efficiently estimate the reduction in the Kondo temperature – a critical parameter signifying the strength of many-body correlations. Specifically, it offers insights into how the Kondo temperature is suppressed by a factor of exp(-\pi V^2 / Jv_F), where V represents the potential scattering strength, J the exchange interaction, and v_F the Fermi velocity. By providing a readily accessible estimation of this reduction, Poor Man’s Scaling serves as a powerful tool for quickly assessing the impact of impurities on the low-temperature behavior of correlated electron systems.

The study’s success in demonstrating Kondo effect survival amidst strong scattering forces demands rigorous examination of its underlying assumptions. It’s not enough to simply observe a phenomenon; one must actively seek conditions that disprove its existence. As Paul Feyerabend noted, “Anything goes.” This isn’t a call for intellectual anarchy, but a recognition that clinging to a single theoretical framework – in this case, perhaps an expectation of Kondo suppression – can blind researchers to unexpected results. The paper’s focus on environmental correlations as a key factor highlights the importance of challenging established paradigms and embracing a methodology of continuous falsification, even when the results seem counterintuitive. A truly robust understanding requires persistent attempts to break the model, not merely confirm it.

Further Down the Rabbit Hole

The persistence of Kondo physics in a demonstrably non-ideal one-dimensional system-one riddled with scattering-is less a revelation than a necessary corrective. It highlights a pervasive tendency to assume, rather than prove, the fragility of quantum coherence. A hypothesis isn’t belief-it’s structured doubt, and the expectation that strong scattering should obliterate the Kondo effect merely reflected a prior commitment to simplicity. Anything confirming expectations needs a second look.

The critical role of environmental correlations, however, introduces new complexities. Defining, and then accurately modeling, those correlations remains the central challenge. Current renormalization group approaches, while powerful, are inherently perturbative. A truly robust understanding will likely require non-perturbative techniques, or perhaps a re-evaluation of the fundamental assumptions underlying existing methods.

Future work must move beyond simply establishing that the Kondo effect survives, to quantifying how it is modified. The suppression of the Kondo temperature under specific conditions offers a promising avenue for investigation, potentially leading to novel means of controlling quantum behavior in these systems. The field should also broaden its scope to explore the interplay between Kondo effects and other emergent phenomena in correlated electron systems.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.11449.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Epic Games Store Free Games for November 6 Are Great for the Busy Holiday Season

- EUR USD PREDICTION

- Battlefield 6 Open Beta Anti-Cheat Has Weird Issue on PC

- How to Unlock & Upgrade Hobbies in Heartopia

- Sony Shuts Down PlayStation Stars Loyalty Program

- The Mandalorian & Grogu Hits A Worrying Star Wars Snag Ahead Of Its Release

- Someone Made a SNES-Like Version of Super Mario Bros. Wonder, and You Can Play it for Free

- ARC Raiders Player Loses 100k Worth of Items in the Worst Possible Way

- Unveiling the Eye Patch Pirate: Oda’s Big Reveal in One Piece’s Elbaf Arc!

- God Of War: Sons Of Sparta – Interactive Map

2026-01-20 05:43