Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals that even as large language models handle increasingly extensive codebases, their ability to reason accurately and avoid distractions remains surprisingly fragile.

A comprehensive analysis demonstrates vulnerabilities in long-context code question answering, highlighting issues with positional sensitivity, reliance on superficial patterns, and the failure to truly understand code semantics.

While large language models (LLMs) demonstrate increasing proficiency in processing extensive code contexts, their capacity for robust and faithful reasoning remains surprisingly fragile. This study, ‘Robustness and Reasoning Fidelity of Large Language Models in Long-Context Code Question Answering’, systematically evaluates state-of-the-art models on long-context code question answering, revealing substantial performance drops when faced with variations in question format, distracting information, or scaled context lengths. The findings demonstrate that LLMs often exhibit positional sensitivities and rely on superficial pattern matching rather than genuine code understanding, highlighting limitations in current evaluation benchmarks. Can we develop more comprehensive metrics and training strategies to ensure LLMs truly reason about code, rather than simply retrieve or mimic it?

The Expanding Horizon of Code Comprehension

The proliferation of Large Language Models (LLMs) has extended to software development, offering assistance with tasks ranging from code generation to bug fixing. However, a significant limitation emerges when these models confront extensive codebases or complex queries demanding comprehension across numerous code segments. LLMs, while proficient at identifying local patterns, often struggle with ‘long-context reasoning’ – the ability to maintain relevant information and dependencies across thousands of tokens. This difficulty stems from the attention mechanisms within these models, which can become computationally expensive and less effective as the input sequence length increases, leading to diminished performance on tasks requiring a holistic understanding of the code’s architecture and logic. Consequently, even relatively simple code-related questions can prove challenging when embedded within a larger, more intricate project.

As software projects evolve and expand, the complexity of their codebases inevitably increases, presenting a significant challenge for automated code analysis tools. Traditional methods, such as static analysis and conventional search-based techniques, often struggle with the sheer volume of information and intricate dependencies within these large-scale projects. Their performance degrades rapidly as codebase size grows, hindering tasks like bug detection, vulnerability assessment, and code understanding. Consequently, there is a pressing need for advanced models – particularly those leveraging large language models – capable of processing and reasoning over extensive code snippets to maintain accuracy and efficiency in the face of increasing software complexity. These models must effectively capture long-range dependencies and contextual information to provide meaningful insights into larger, more intricate systems.

Assessing the efficacy of large language models on complex codebases demands evaluation techniques that transcend traditional code completion benchmarks. Current methods often focus on isolated snippets, failing to capture a model’s ability to reason across extensive, interconnected code. Researchers are now developing benchmarks specifically designed to probe long-context understanding, presenting models with tasks requiring them to identify dependencies, trace logic flows, and understand the interplay between distant code sections. These evaluations often involve presenting models with questions about the overall functionality of a program, requiring them to synthesize information from numerous files, or asking them to debug errors that span a large codebase. The goal is to move beyond superficial correctness and measure a model’s genuine comprehension of complex software systems, paving the way for more reliable and sophisticated code-related applications.

Charting Progress: LongCodeBench and its Evolution

LongCodeBench was initially designed as a benchmark specifically for evaluating the long-context code understanding capabilities of language models using the Python programming language. This initial focus allowed for the establishment of a foundational performance baseline across a standardized dataset of code-related questions requiring analysis of extensive code segments. The selection of Python was strategic, given its widespread use in software development and machine learning, providing a readily available corpus of code for benchmark construction and evaluation. Early results from LongCodeBench provided quantifiable metrics regarding a model’s ability to correctly answer questions when the necessary information was embedded within thousands of tokens of code, highlighting limitations in existing model architectures regarding context length and information retrieval.

LongCodeU represents an expansion of the original LongCodeBench, increasing both the number of large language models (LLMs) subjected to long-context code question answering evaluations and the diversity of assessed code understanding capabilities. This extension incorporates a broader range of tasks beyond the initial Python focus, including code completion, bug fixing, and code translation. The expanded benchmark utilizes a larger and more varied dataset of code examples and questions, designed to provide a more comprehensive assessment of LLM performance on complex, real-world coding challenges. LongCodeU aims to facilitate more robust comparisons between models and track improvements in their ability to reason about and manipulate extended code sequences.

Evaluation using LongCodeBench has been extended to include the COBOL programming language to specifically assess the cross-language generalization capabilities of large language models. This expansion moves beyond evaluating performance solely on Python, providing insights into a model’s ability to understand and reason about code written in a significantly different paradigm and with a different syntax. COBOL was selected due to its prevalence in legacy business systems and its structural differences from more commonly used languages, offering a challenging test case for evaluating true code understanding rather than memorization of common patterns. Performance on COBOL tasks is reported alongside Python results, allowing for a comparative analysis of a model’s adaptability and broad coding proficiency.

LongCodeBench and LongCodeU utilize the ‘Needle in a Haystack’ paradigm to assess a model’s capacity for retrieving specific information from large codebases. This technique involves embedding a crucial code snippet – the ‘needle’ – within a significantly larger, functionally unrelated code block – the ‘haystack’. Model performance is then measured by its ability to accurately identify and extract the ‘needle’ despite the surrounding irrelevant code. This approach isolates the model’s long-range dependency handling and information retrieval skills, providing a quantitative assessment of its ability to process extensive code contexts and pinpoint relevant details.

Unveiling the Shadows: Positional Bias and the Recognition-Generation Gap

Positional bias in large language models (LLMs) refers to the phenomenon where a model’s performance varies depending on the location of relevant information within the provided context window. Specifically, many models demonstrate a strong recency bias, meaning they exhibit higher accuracy and recall for information presented towards the end of the context. This is likely due to architectural limitations or training data distributions that prioritize more recent tokens. Consequently, performance can degrade significantly when crucial information is positioned earlier in the input sequence, even if the total context length remains within the model’s capacity; this impacts tasks like question answering and code completion where the location of relevant data isn’t fixed.

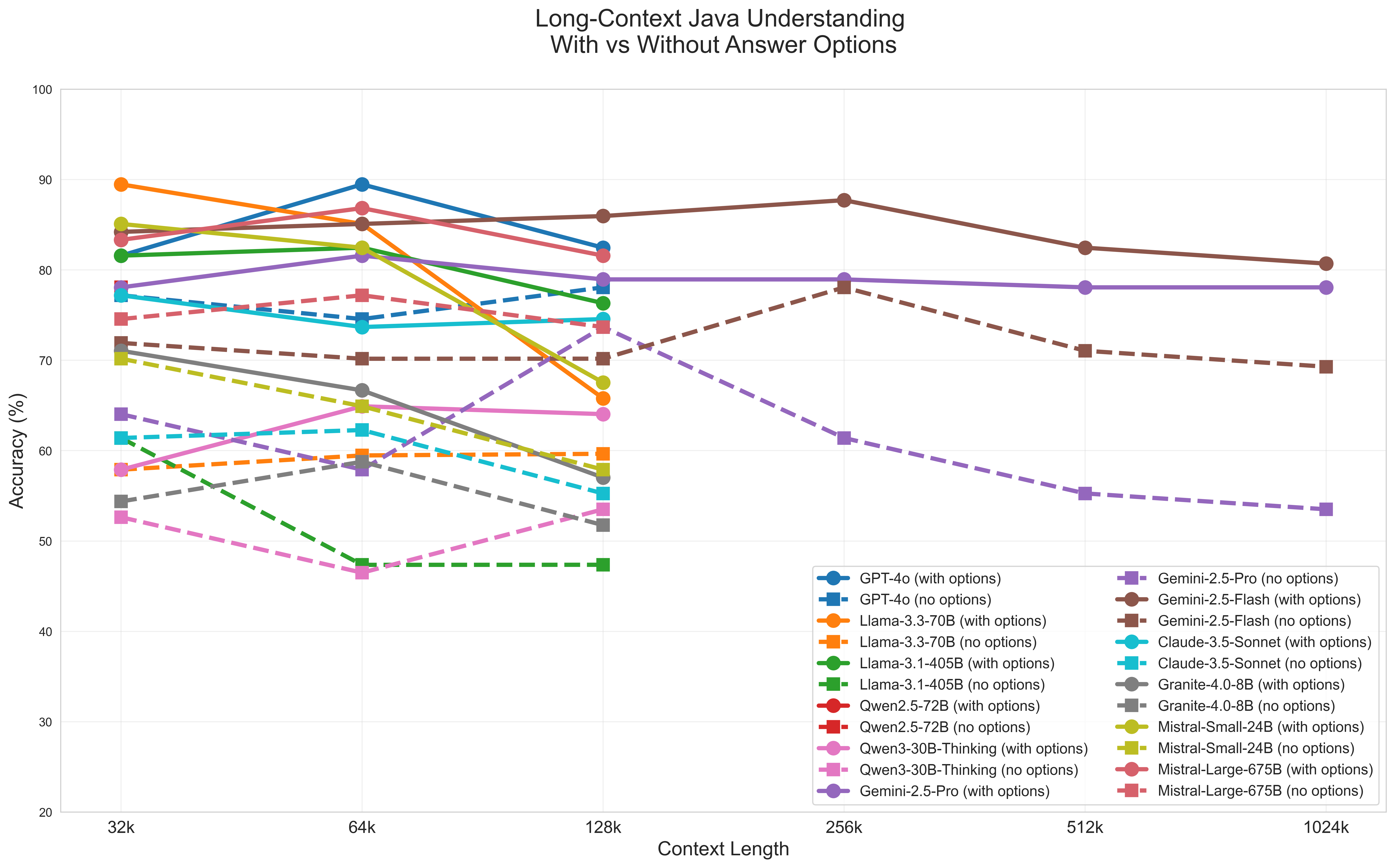

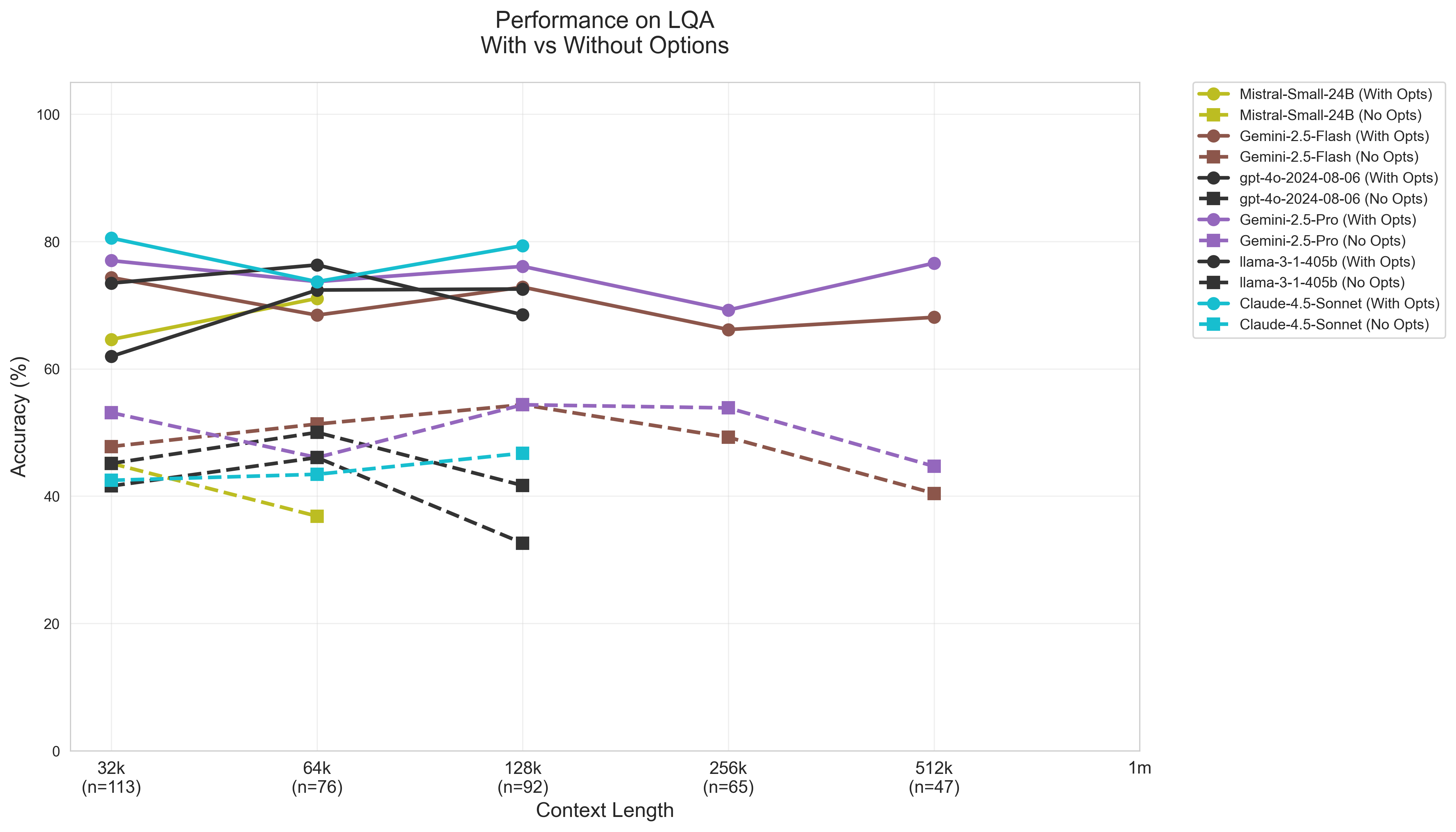

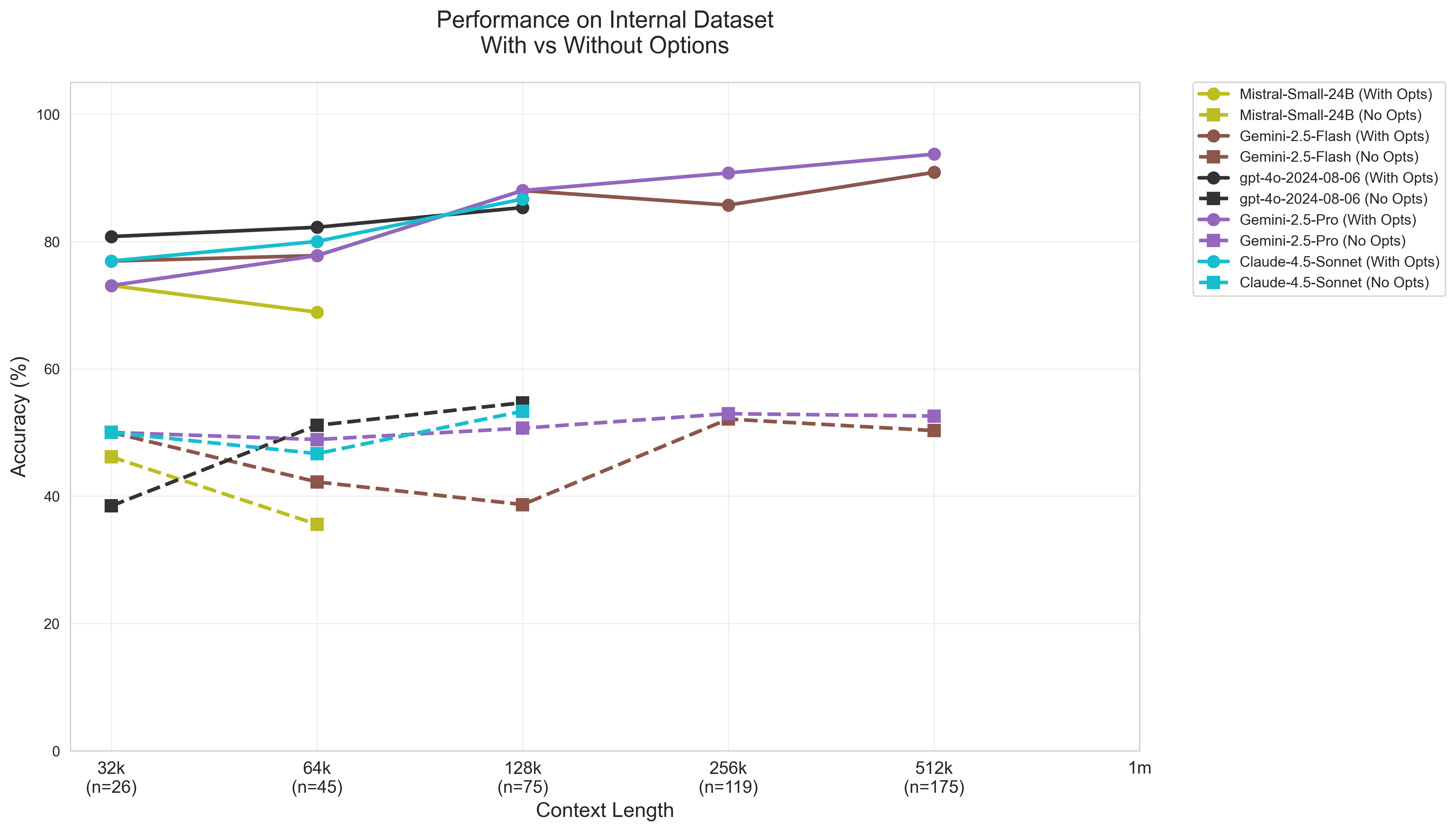

The discrepancy between a model’s ability to identify correct answers from a provided set and its capacity to produce those same answers independently is known as the Recognition-Generation Gap. Quantitative analysis demonstrates this gap through performance comparisons; models frequently exhibit a reduction in accuracy ranging from 15 to 35 percentage points when transitioning from multiple-choice question answering (where the correct answer is selectable) to open-ended or generative question answering (requiring independent answer formulation). This suggests that while models can effectively assess correctness, they struggle with the complex reasoning and knowledge recall necessary for autonomous answer creation.

Current evaluation methodologies for large language models increasingly utilize Java code sourced from established, open-source software repositories. Specifically, projects such as Cassandra, Dubbo, and Kafka are being integrated into datasets to provide realistic and complex codebases for model assessment. This approach aims to move beyond synthetic or simplified code examples and instead benchmark performance against actual, production-level software systems, enabling a more accurate understanding of a model’s capabilities in real-world software engineering tasks. The inclusion of these projects allows for evaluation of code comprehension, bug fixing, and code generation skills within the context of large, complex applications.

Model performance is significantly affected by context length, particularly when processing extensive codebases. Representing larger codebases necessitates a greater number of tokens, potentially exceeding the model’s effective context window and leading to decreased accuracy. Empirical data demonstrates this effect; Llama-3.1-405B, when evaluated on COBOL code with a context length of 128k tokens positioned at the beginning of the input, achieved only 40.00% accuracy, illustrating the challenges of maintaining performance with extended contexts.

A Comparative Landscape: Evaluating Long-Context Proficiency

Current evaluations are actively benchmarking the long-context code understanding capabilities of several prominent Large Language Models (LLMs). These include, but are not limited to, GPT-4o, Gemini, Claude, Llama, Mistral, and Qwen. The assessment focuses on their ability to process and reason about extended code sequences, moving beyond traditional short-context limitations. This comparative analysis aims to determine which models demonstrate the most effective performance in tasks requiring comprehension of larger codebases and complex dependencies, and to identify areas for continued development in long-context reasoning within the LLM landscape.

Large language model evaluation utilizes both Multiple-Choice Question Answering (MCQA) and Open-Ended Question Answering (OEQA) formats to provide a comprehensive assessment of reasoning capabilities. MCQA tasks measure a model’s ability to select the correct answer from a predefined set, focusing on knowledge recall and selection accuracy. Conversely, OEQA requires models to generate answers independently, evaluating their capacity for complex reasoning, synthesis, and nuanced understanding. The combination of these formats allows researchers to differentiate between a model’s ability to recognize correct information and its ability to formulate coherent and logically sound responses, providing a more holistic performance profile.

Granite, an architecture developed by IBM Research, is being investigated as a solution for long-context code tasks by employing a retrieval-augmented generation approach. Unlike standard transformer models, Granite utilizes a differentiable neural dictionary to retrieve relevant code snippets from a large external knowledge base. This allows the model to effectively handle significantly longer input sequences-potentially exceeding 128k tokens-by focusing on only the most pertinent information. The architecture is designed to mitigate the computational cost and performance degradation typically associated with processing extremely long contexts, offering a potential alternative to scaling transformer sizes or relying solely on attention mechanisms for long-range dependencies.

Performance evaluations reveal variations in long-context code understanding across different Large Language Models. Gemini-2.5-Pro exhibits a degree of robustness, maintaining accuracy between 44% and 54% when processing Python code across context lengths ranging from 32,000 to 512,000 tokens. In contrast, Llama-3.1-405B demonstrates higher accuracy – 76.32% – when answering multiple-choice questions regarding Java code, but this performance drops significantly to 58% when the same model is tasked with open-ended Java code completion or reasoning without provided options.

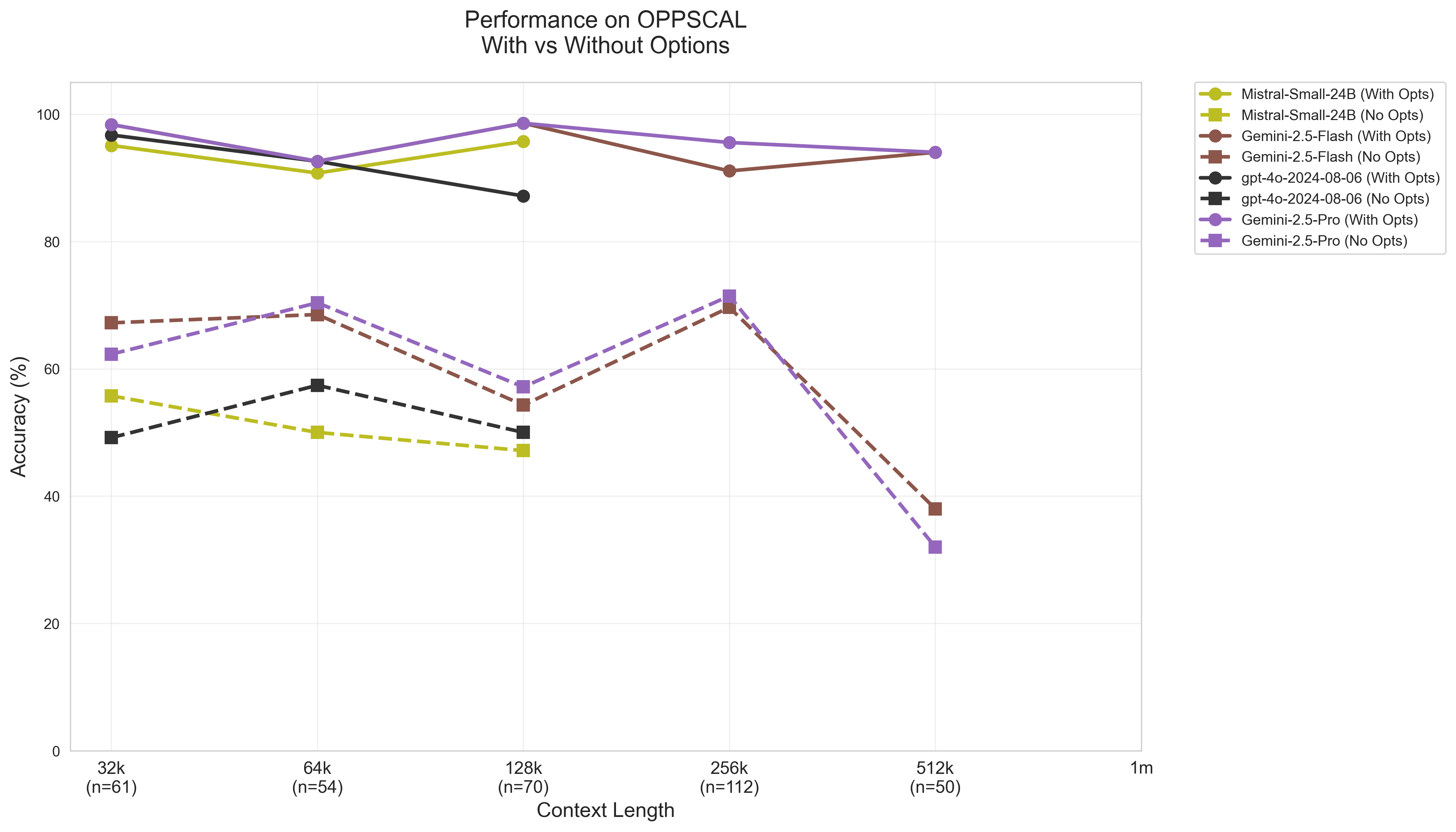

The OPPSCAL Dataset provides a benchmark for evaluating long-context reasoning capabilities specifically within the domain of legacy systems, utilizing code derived from COBOL. This dataset is designed to assess a model’s ability to process and understand extensive codebases characteristic of older applications. Current evaluations demonstrate that models can achieve accuracy rates up to 98% when provided with multiple-choice options during testing on this dataset, indicating a potential for effective reasoning when aided by constrained answer selection; however, performance may vary without such aids, highlighting the importance of the testing methodology when analyzing results.

Towards Robustness: Charting Future Directions in Long-Context Reasoning

Progress in long-context code question answering hinges significantly on the continued refinement of benchmarks and evaluation techniques. Current methods often struggle to accurately assess a model’s ability to utilize information across extensive codebases, leading to an incomplete understanding of true capabilities and hindering meaningful advancement. More sophisticated benchmarks are needed, moving beyond simple accuracy metrics to incorporate measures of information retrieval precision, contextual understanding, and the capacity to synthesize knowledge from distant code segments. Furthermore, evaluations must prioritize diversity, encompassing a wider range of programming languages, code complexities, and real-world software engineering scenarios to ensure models generalize effectively and address practical challenges faced by developers. Without robust and comprehensive evaluation tools, identifying genuine breakthroughs and guiding future research directions remains a substantial obstacle in the field.

Large language models often exhibit a pronounced positional bias, performing significantly better when relevant information appears later in the input sequence – a phenomenon akin to prioritizing recent evidence. This limitation, coupled with a ‘recognition-generation gap’ – where a model can identify correct code but struggles to reliably produce it – hinders their ability to effectively reason over extended code contexts. Overcoming these challenges is paramount; future research must focus on techniques that allow models to equitably weigh information regardless of its position and bridge the gap between comprehension and generation. Successfully addressing these issues promises to unlock the full potential of LLMs for complex code question answering, allowing them to navigate and utilize vast codebases with greater accuracy and reliability.

The current landscape of long-context code question answering relies heavily on evaluations within a limited set of programming languages and often utilizes synthetic or simplified codebases. To truly gauge the capabilities of large language models, evaluation must broaden significantly. Incorporating a wider array of languages – beyond Python and Java – will reveal how well these models generalize across different syntaxes and paradigms. More importantly, assessing performance on real-world codebases – complete with the complexities of legacy systems, diverse coding styles, and intricate dependencies – is crucial. This shift will provide a more accurate and practical understanding of a model’s ability to reason about and manipulate code in realistic scenarios, ultimately driving the development of more robust and reliable solutions for software engineering tasks.

The pursuit of enhanced long-context reasoning in large language models necessitates exploration beyond conventional architectures and training paradigms. Current models often exhibit a pronounced “recency bias,” where performance dramatically improves as relevant information appears later in the input sequence; for instance, the Granite-4-8B model achieves 62.22% accuracy in COBOL question answering when the answer is positioned at the end of the context, a stark contrast to the 15.56% accuracy observed when the answer resides at the beginning. This disparity underscores the limitations of existing attention mechanisms in effectively processing information across extended contexts. Consequently, research is increasingly focused on innovative approaches – including modified transformer designs, improved positional encoding schemes, and novel training objectives – to mitigate this bias and enable models to consistently and accurately reason over long-range dependencies, ultimately unlocking their full potential for complex code understanding and generation tasks.

The study reveals a disheartening truth: these large language models, despite their capacity to ingest vast stretches of code, often mistake correlation for comprehension. They locate answers, but seldom understand them, a failing exacerbated by the models’ sensitivity to irrelevant information. It echoes a sentiment shared by David Hilbert, who once stated, “One must be able to say at any time exactly what one knows and what one does not.” The research suggests these systems, even with long context windows, frequently don’t know what they don’t know, instead projecting patterns onto the code and mistaking proximity for reasoning. Each successful retrieval feels less like a triumph of intelligence, and more like a temporary reprieve from inevitable failure.

What’s Next?

The exercise reveals, yet again, that extending the apparent reach of these systems is not the same as deepening their understanding. Architecture is how one postpones chaos, and the current trend of scaling context windows merely delays the inevitable confrontation with fundamental limits. The findings regarding positional sensitivity and susceptibility to irrelevant information are not bugs, but emergent properties of a design predicated on pattern completion, not genuine reasoning. One builds larger sieves, expecting finer grain, but the substrate remains the same.

Future work will undoubtedly explore increasingly elaborate retrieval mechanisms and attention architectures. However, the core challenge persists: these models excel at appearing to comprehend, while demonstrating a fragile grasp of semantic integrity. There are no best practices – only survivors. The field will likely shift from a focus on ‘long context’ as a feature, to an acknowledgement that context, in its entirety, is an illusion – a necessary fiction for approximating intelligence.

The true measure of progress will not be the length of code a model can process, but the elegance with which it can ignore irrelevant detail. Order is just cache between two outages. The next generation of systems will need to internalize a principle of ‘cognitive frugality’ – a willingness to sacrifice completeness for robustness. Perhaps then, these systems will move beyond sophisticated mimicry, and begin to approximate something akin to comprehension.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.17183.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Top 10 Must-Watch Isekai Anime on Crunchyroll Revealed!

- How to Unlock & Visit Town Square in Cookie Run: Kingdom

- Scopper’s Observation Haki Outshines Shanks’ Future Sight!

- Enshrouded: Giant Critter Scales Location

- Deltarune Chapter 1 100% Walkthrough: Complete Guide to Secrets and Bosses

- Multiplayer Games That Became Popular Years After Launch

- All Carcadia Burn ECHO Log Locations in Borderlands 4

- All Shrine Climb Locations in Ghost of Yotei

- 10 Best Indie Games With Infinite Replayability

- Gold Rate Forecast

2026-02-21 15:37