Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new framework enhances conformal prediction, offering robust uncertainty quantification even when training data is limited.

This paper delivers statistical guarantees for conformal predictors when applied to small datasets, leveraging surrogate models to improve coverage.

While conformal prediction offers robust uncertainty quantification for machine learning models, its standard statistical guarantees degrade with limited calibration data-a common scenario in real-world applications. This paper, ‘Reliable Statistical Guarantees for Conformal Predictors with Small Datasets’, addresses this limitation by introducing a novel guarantee that provides probabilistic coverage information for individual conformal predictors, even with small datasets. The proposed framework converges to standard conformal prediction for larger datasets, yet maintains reliability where traditional methods falter. Will this refined approach unlock broader, more trustworthy deployment of conformal prediction in data-scarce settings?

Bridging Fidelity and Efficiency with Surrogate Models

Numerous real-world simulations, particularly those modeling complex physical phenomena or intricate systems, demand substantial computational resources. These high costs stem from the need to solve numerous equations, often requiring extensive processing time and powerful hardware. Consequently, tasks like design optimization, uncertainty quantification, and real-time prediction become prohibitively slow or even infeasible. For example, simulating airflow around an aircraft wing, predicting weather patterns, or modeling protein folding can each require days or weeks of computation on supercomputers. This computational burden significantly hinders rapid iteration and exploration of design spaces, slowing down innovation and delaying critical decision-making processes across diverse fields like engineering, climate science, and drug discovery.

Surrogate models represent a powerful strategy for navigating the limitations of computationally intensive simulations. These models, often leveraging techniques like Gaussian processes or neural networks, learn the relationship between input parameters and system outputs from a limited number of high-fidelity simulations. This allows for a rapid and cost-effective prediction of system behavior across a vast design space, circumventing the need for repeated execution of the original, demanding simulation. Consequently, surrogate models enable efficient optimization, uncertainty quantification, and sensitivity analysis – processes that would be impractical or impossible with the full model. The accuracy of a surrogate model is inherently tied to the quality and quantity of the training data, but even a moderately accurate surrogate can dramatically accelerate the pace of scientific discovery and engineering innovation.

Quantifying Predictive Uncertainty

An uncertainty model is a critical component in evaluating the trustworthiness of predictions generated by a surrogate model. Because surrogate models are approximations of more complex systems, quantifying the uncertainty associated with their outputs is essential for informed decision-making. This quantification provides a measure of confidence in the prediction, allowing users to understand the potential range of error and to assess the risk associated with relying on that prediction. Without an uncertainty model, it is impossible to determine whether a given prediction is likely to be accurate or represents an outlier resulting from the surrogate’s limitations. The model establishes a probability distribution over possible outcomes, reflecting the inherent variability and imprecision of the surrogate.

A Calibration Set is a subset of data, independent of the training data used to build the surrogate model, used specifically to quantify the relationship between predicted confidence and actual observation frequency. This set enables the calculation of metrics like calibration curves and Expected Calibration Error (ECE), which assess the reliability of the surrogate’s probabilistic predictions. The size of the Calibration Set is a critical parameter; insufficient data can lead to unstable or inaccurate calibration estimates, while excessively large sets increase computational cost without necessarily improving accuracy. Data within the Calibration Set should represent the expected operating conditions of the surrogate to ensure the resulting uncertainty estimates are relevant and trustworthy for real-world applications.

A dedicated Test Set is essential for validating the generalization ability of an uncertainty model, meaning its performance on previously unseen data. This set, independent from the Calibration Set used during training, provides an unbiased evaluation of the model’s predictive accuracy and reliability. Metrics calculated on the Test Set, such as calibration error or prediction interval coverage probability, quantify how well the model’s predicted uncertainties align with observed outcomes on new data. Without a separate Test Set, evaluations based on the Calibration Set are prone to overfitting and do not accurately reflect real-world performance, potentially leading to overconfidence in unreliable predictions.

Conformal Prediction: Guaranteeing Reliable Coverage

Conformal Prediction (CP) is a distribution-free method for quantifying the uncertainty of a machine learning model’s predictions. Unlike traditional prediction intervals that rely on assumptions about the data distribution, CP provides validity guarantees regardless of the underlying model or data. This is achieved by constructing prediction intervals based on a nonconformity measure, which quantifies how unusual a new data point is relative to a calibration set. Specifically, CP ensures that, over a long series of predictions, the true value will fall within the predicted interval at least $1 – \alpha$ percent of the time, where $\alpha$ is a user-defined error rate. This coverage guarantee holds true even with complex models and non-independent and identically distributed data, making it a robust approach to reliable prediction.

Conformal prediction utilizes order statistics to quantify the uncertainty of predictions without requiring assumptions about the underlying data distribution. Given a calibration set and a new test instance, the algorithm calculates the rank of the test instance’s prediction within the set of predictions made on the calibration data. This rank, normalized by the total number of calibration samples, n, produces a p-value representing the proportion of calibration examples with predictions worse than the test instance. The fractional part of this p-value, calculated as $p – \lfloor p \rfloor$, is then used to determine the interval’s boundaries, ensuring that the coverage probability is maintained across different datasets and models. Specifically, the interval is constructed by considering the $1 – \alpha$ quantile of the order statistics derived from the calibration set, where $\alpha$ is the desired error rate.

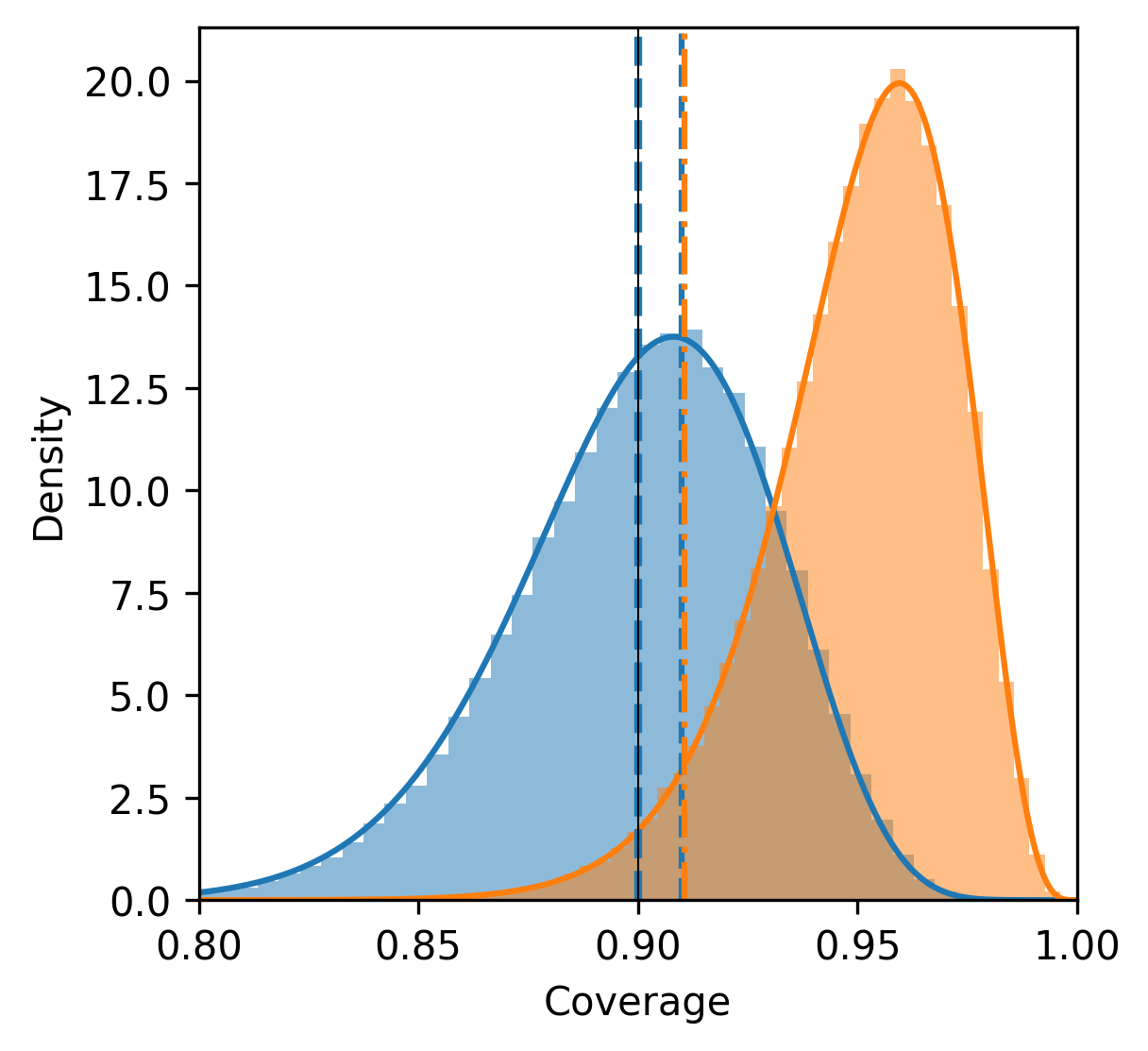

Standard conformal prediction assumes an infinite calibration set, leading to inaccuracies when dealing with limited data. To address this, the Beta distribution is employed to model the distribution of coverage probabilities. This approach acknowledges the uncertainty inherent in estimating coverage with small calibration sets and provides a more realistic assessment of prediction validity. Specifically, the Beta distribution, parameterized by $α$ and $β$, is used to represent the probability of observing a given coverage level, allowing for adjustments to prediction intervals based on the size and characteristics of the calibration data. This results in improved robustness and maintained reliability even with reduced sample sizes, effectively mitigating the limitations of traditional conformal prediction in small-data scenarios.

From Coverage to Trustworthy Predictions

Coverage serves as a fundamental metric for evaluating the reliability of predictive models, specifically quantifying the proportion of test examples that fall within the model’s predicted intervals. This assessment, however, is inherently local, focusing on the performance for a given set of test data and providing insight into how well the model’s uncertainty estimates align with observed outcomes for those specific instances. A high coverage indicates that the model is, on average, capturing the true values within its predicted range for the tested data, while low coverage suggests underestimation of uncertainty or poor calibration. Although a useful indicator, coverage alone doesn’t offer a comprehensive view; it’s crucial to consider it alongside other metrics and understand that it represents a snapshot of reliability rather than a global guarantee. Establishing a desired level of coverage is therefore a key step in defining acceptable performance for surrogate and uncertainty models, paving the way for more robust and trustworthy predictions.

While coverage quantifies how often predictions contain the true value for a single test example, marginal coverage offers a more comprehensive reliability assessment by considering the expected coverage across many such examples. This extension moves beyond local accuracy to a global measure, effectively averaging the coverage achieved over a distribution of possible scenarios. By calculating the expected proportion of times predictions successfully encapsulate the true value – considering numerous “realizations” or repetitions of the prediction process – researchers gain insight into the overall trustworthiness of a model’s uncertainty estimates. A high marginal coverage indicates that, on average, the model consistently provides reliable predictions, offering a robust indicator of its performance across a wider range of inputs and conditions, and forming a critical foundation for applications demanding dependable risk assessment.

Defining a minimum acceptable coverage level is paramount when evaluating the reliability of surrogate and uncertainty models, as it establishes a quantifiable threshold for performance. This work introduces a guarantee that bounds the discrepancy between the expected coverage – the average coverage across numerous model realizations – and the desired coverage specified by the practitioner. Specifically, the proposed bound demonstrates that this difference will be less than or equal to $1 / (N_{cal} + 1)$, where $N_{cal}$ represents the number of calibration samples utilized. This provides a practical, mathematically-grounded means of assessing whether the models are sufficiently reliable for their intended applications, offering assurance that the predicted uncertainty accurately reflects the true variability of the system being modeled.

The pursuit of reliable uncertainty quantification, as detailed in this work, echoes a fundamental principle of systemic integrity. This paper directly addresses the challenge of limited data within conformal prediction, striving for statistical guarantees where conventional methods falter. It is reminiscent of Marvin Minsky’s observation: “The more we learn about intelligence, the more we realize how much of it is just good perceptual organization.” The presented framework, by focusing on surrogate models and refined conformal prediction techniques, essentially aims to impose a clearer ‘perceptual organization’ on the data, extracting meaningful predictions even from sparse information. This structural approach, prioritizing clarity and boundaries, enables the system to function robustly, mirroring the resilience inherent in well-defined organisms.

Where Do We Go From Here?

This work addresses a perennial tension: the desire for statistical rigor colliding with the reality of limited data. The modification to conformal prediction offered here is not a panacea, but a carefully considered acknowledgement that systems break along invisible boundaries-if one cannot see the limits of applicability, pain is coming. Future efforts must concentrate on precisely mapping those boundaries. Coverage guarantees, even when met, are insufficient without understanding where those guarantees begin to erode.

A critical path forward involves a deeper investigation into the surrogate models themselves. The choice of surrogate, and the inherent biases it introduces, remain largely unexplored within the conformal framework. To treat all models as equally ‘black box’ is a simplification that invites failure. Structure dictates behavior, and a more nuanced understanding of model architecture, and its impact on conformal prediction’s performance, is paramount.

Ultimately, the field must move beyond simply achieving coverage, and focus on characterizing the nature of that coverage. What types of errors are most likely when data is scarce? How can conformal predictors be adapted to provide more informative uncertainty estimates – not just a ‘yes/no’ on inclusion, but a probability distribution reflecting the degree of confidence? These are the questions that will determine whether conformal prediction evolves from a promising technique to a truly robust tool.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2512.04566.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Epic Games Store Free Games for November 6 Are Great for the Busy Holiday Season

- How to Unlock & Upgrade Hobbies in Heartopia

- Battlefield 6 Open Beta Anti-Cheat Has Weird Issue on PC

- EUR USD PREDICTION

- Sony Shuts Down PlayStation Stars Loyalty Program

- The Mandalorian & Grogu Hits A Worrying Star Wars Snag Ahead Of Its Release

- Someone Made a SNES-Like Version of Super Mario Bros. Wonder, and You Can Play it for Free

- Unveiling the Eye Patch Pirate: Oda’s Big Reveal in One Piece’s Elbaf Arc!

- God Of War: Sons Of Sparta – Interactive Map

- ARC Raiders Player Loses 100k Worth of Items in the Worst Possible Way

2025-12-07 19:41