Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new quantum bit commitment protocol leverages phase encoding to offer practical security despite theoretical vulnerabilities to known attacks.

This review details a phase-based protocol resistant to Mayers attacks due to the demanding resources required for successful implementation, utilizing entanglement and phase-averaged coherent states.

Realizing unconditionally secure bit commitment remains a foundational challenge in cryptography due to inherent limitations imposed by no-go theorems. This work introduces a novel quantum optical bit commitment protocol, the ‘Phase-Based Bit Commitment Protocol’, leveraging entanglement and phase encoding to address this need. While theoretically susceptible to Mayers’ attack, our protocol presents practical hurdles to successful implementation due to the demanding requirements for high-energy entanglement and precise state preparation. Could these practical constraints offer a viable pathway toward secure communication in realistic network environments, despite the limitations of idealized security proofs?

The Illusion of Perfect Commitment

Quantum bit commitment represents a foundational element in the pursuit of unconditionally secure communication, offering a mechanism where one party, typically designated Alice, commits to a value without revealing it, while retaining the ability to reveal it later. This process isn’t merely about concealing information; it’s about establishing a binding promise – a commitment – that cannot be altered retroactively. The core principle hinges on leveraging the laws of quantum physics to ensure that any attempt by Alice to change her committed value after the commitment phase would inevitably leave a detectable trace, preventing deceit. Ideally, this protocol allows Bob to verify the integrity of the committed value upon revelation, solidifying a secure foundation for more complex cryptographic tasks, like secure computation and verifiable delegation – though, as theoretical work demonstrates, achieving perfect, unconditional security proves surprisingly elusive.

Despite the promise of quantum bit commitment as a fundamentally secure communication method, theoretical investigations known as ‘no-go theorems’ reveal inherent limitations to achieving absolute, unconditional security. These theorems demonstrate that, under reasonable assumptions about the capabilities of adversaries and the laws of physics, any bit commitment scheme is susceptible to some degree of cheating. Specifically, these proofs often rely on demonstrating that perfect commitment would violate established principles like relativistic causality or require infinite resources. This isn’t to say quantum bit commitment is useless; rather, it necessitates a shift towards practical security – aiming for ϵ-security, where the probability of a successful cheat is bounded by a quantifiable, albeit non-zero, value ε. The pursuit, therefore, focuses on minimizing ε to a level that renders cheating computationally or economically infeasible, acknowledging that absolute security remains an elusive ideal.

Initial quantum bit commitment protocols, such as the Bennett-Brassard scheme, weren’t impervious to attack, demonstrating a crucial vulnerability even within the realm of quantum mechanics. These early designs proved susceptible to sophisticated cheating strategies leveraging quantum entanglement, where a malicious party could potentially manipulate the system to gain information before the commitment was revealed. Consequently, research shifted from striving for absolute, unconditional security – an unattainable goal – towards achieving what is known as ϵ-security. This pragmatic approach acknowledges the possibility of cheating, but bounds its probability; a protocol with ϵ-security guarantees that the chance of either Alice or Bob successfully deceiving the other remains below a predefined threshold, represented by the value of ϵ. This represents a move towards realistically secure systems, rather than theoretically perfect, but ultimately breakable, ones.

Exploiting the Cracks: When Commitment Fails

The Mayers attack, first demonstrated in 1996, revealed a fundamental vulnerability in early quantum bit commitment protocols. This attack exploits the time between a sender committing to a bit value and a receiver verifying that commitment. Specifically, the sender, rather than immediately finalizing the quantum state representing the committed bit, can delay this finalization and, crucially, subtly alter the state before verification. Because the commitment is based on the laws of quantum mechanics, this alteration can effectively change the committed bit without leaving a detectable trace for an honest receiver. This is possible because the initial quantum state isn’t irrevocably fixed at the time of commitment, allowing the sender to exploit this delay to their advantage and potentially deceive the receiver.

The Mayers attack on quantum bit commitment exploits the properties of entangled states, specifically Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen (EPR) pairs, to allow the sender to potentially alter the committed bit after a partial commitment. This is achieved by delaying full commitment and manipulating one particle of the entangled pair while concealing the change through the entanglement with the receiver’s particle. The primary practical difficulty in executing this attack stems from the requirement of generating high-energy entangled photon states; the complexity of approximating these states scales with a photon number cutoff N, directly impacting the fidelity and feasibility of the attack. Higher values of N are needed to more closely approximate the ideal entangled state, but also increase the technological hurdles in generating and maintaining these states.

The security of quantum bit commitment schemes is directly impacted by the practical challenges of generating the necessary high-fidelity quantum states; specifically, approximating the ideal states requires a truncation of the Hilbert space, parameterized by a photon number cutoff, N. Increasing N improves the fidelity of the approximated state, but also exponentially increases the resources required for state preparation and measurement. This trade-off between fidelity and resource cost introduces a quantifiable limitation on the robustness of commitment schemes against active adversaries attempting to exploit vulnerabilities like the Mayers attack, as imperfect states introduce a non-negligible probability of successful deception. Consequently, fortifying these schemes necessitates either improvements in quantum state preparation technology or the development of protocols tolerant to state imperfections.

Patching the Holes: Towards More Robust Commitment

Quantum key distribution (QKD) protocols rely on the transmission of quantum states to establish a secure key between two parties. Current vulnerabilities to attacks, such as photon number splitting (PNS), necessitate research into state design that mitigates these risks. A primary approach involves crafting quantum states that appear identical to an eavesdropper, effectively concealing any information about the key. This indistinguishability creates a secure commitment, preventing an attacker from gaining knowledge of the transmitted information without introducing detectable errors. Successful implementation of such states would enhance the security of QKD systems against a range of active and passive attacks by ensuring the confidentiality of the established key.

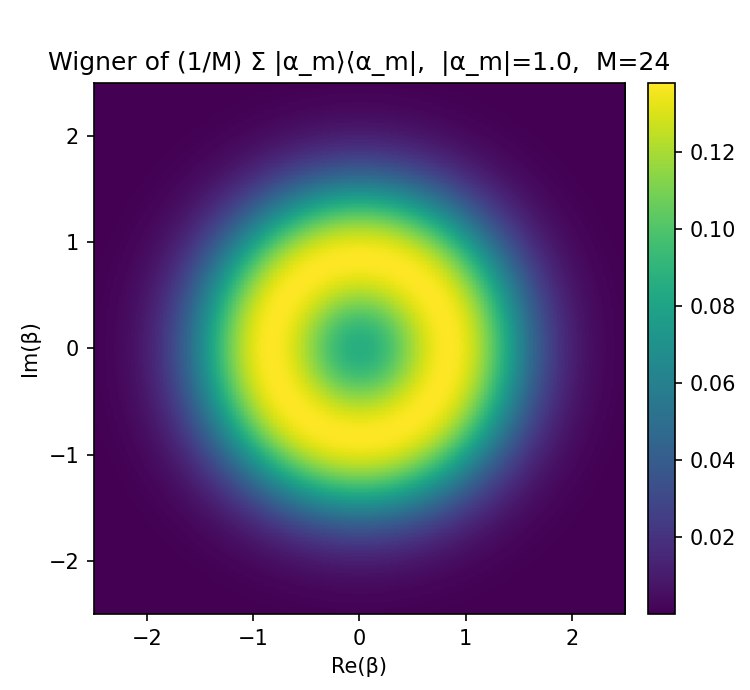

Phase averaged coherent states are being investigated as a potential method for constructing quantum states resistant to eavesdropping. These states, derived from coherent states subjected to phase averaging, exhibit properties that make them difficult to distinguish from vacuum states for an attacker without complete knowledge of the phase shifts applied. Analysis using the Wigner function, a quasiprobability distribution, allows for the characterization of these states in phase space, providing a means to assess their security and distinguishability. The Wigner function effectively reveals the non-classical characteristics of the phase-averaged states, demonstrating their potential for secure quantum communication protocols by obscuring information from potential interceptors.

The Stellar Rank provides a quantifiable metric for the complexity of phase-averaged coherent states used in secure communication protocols. This rank is calculated utilizing the Mittag-Leffler Function, allowing for precise characterization of state complexity. Critically, the parameter ‘k’ defining the Stellar Rank scales cubically with ‘M’ k \propto M^3, where ‘M’ represents the number of phase shifts applied to the state. This cubic scaling indicates that achieving higher levels of security – requiring a greater number of phase shifts – results in a rapidly increasing computational burden for potential eavesdroppers attempting to distinguish the states, but also increases the resources required for legitimate transmission and reception.

The Limits of Perfection: A Pragmatic View of Security

Contemporary cryptographic security models are increasingly adopting the Quantum Storage Model, a pragmatic shift acknowledging the inherent difficulties in constructing perfect quantum memories. Traditional security proofs often rely on idealized assumptions about storing quantum information indefinitely without error; however, real-world quantum storage is susceptible to decoherence and loss. The Quantum Storage Model relaxes these unrealistic expectations, instead focusing on security guarantees achievable with limited quantum storage capabilities. This approach allows researchers to develop more practical and realistic security protocols, quantifying the impact of storage limitations on overall system robustness. By explicitly accounting for storage imperfections, the model provides a more accurate assessment of achievable security levels and guides the design of quantum-resistant cryptographic systems that can function effectively within the constraints of current and near-future technology.

Current advancements in quantum security are increasingly focused on defining security criteria not by idealized, but by achievable quantum operations, a concept formalized through the study of Separable Operations. This approach acknowledges that practical quantum devices face limitations in their operational capabilities and seeks to build security proofs grounded in what is physically realizable. Rather than assuming perfect quantum control, researchers are establishing security standards based on operations that can be reliably implemented with existing or near-future technology. This shift is crucial because it allows for the development of cryptographic protocols that are demonstrably secure against attacks using realistic quantum resources, moving beyond theoretical vulnerabilities predicated on unattainable operational perfection. By focusing on Separable Operations, the field aims to bridge the gap between theoretical quantum security and its practical implementation, bolstering confidence in the resilience of future communication systems.

Current security model refinements increasingly incorporate the principles of relativity to address vulnerabilities arising from information transmission and observation. This approach acknowledges that the speed of light imposes fundamental limits on communication, impacting the feasibility of certain cryptographic protocols and the timing of security breaches. By applying relativistic constraints – specifically considering concepts like spacetime and causality – researchers are developing models that account for the physical limitations of information exchange. This leads to more robust security proofs, as the models inherently factor in the impossibility of instantaneous communication or backwards-in-time signaling, thereby preventing theoretical attacks that rely on such impossibilities. The integration of relativistic principles offers a pathway toward cryptographic systems that are not only mathematically sound but also physically plausible, enhancing their resilience against both classical and quantum threats.

The pursuit of unbreakable commitment schemes, as detailed in this protocol, feels predictably optimistic. It echoes a common refrain: build something theoretically sound, then watch production expose all the hidden compromises. This work, focusing on entanglement and phase-averaged coherent states, is no different. The authors acknowledge vulnerability to a Mayers attack, but posit practical difficulties in execution. One suspects these ‘difficulties’ will simply become new forms of attack vectors. As Donald Davies observed, “It is easier to find an existing problem and solve it than to invent a new one.” The elegance of quantum mechanics doesn’t guarantee security; it merely shifts the battleground. The protocol’s reliance on high-energy entanglement, while intended as a defense, is ultimately just another dependency destined to introduce its own set of failures.

Where Do We Go From Here?

This phase-based protocol, like so many attempts at quantum security, skirts the line between theoretical elegance and practical futility. The authors correctly identify the Mayers attack as an ever-present threat, but seem to imply implementation complexity constitutes a defense. History suggests this is merely delaying the inevitable; production systems will find a way. Someone, somewhere, will optimize that attack, or discover a new one exploiting unforeseen weaknesses in state preparation. It’s always the case.

The reliance on high-energy entanglement feels… familiar. It recalls previous schemes that demanded tolerances bordering on the physically impossible. The insistence on phase-averaged coherent states is a clever attempt at mitigation, but merely shifts the problem. The signal-to-noise ratio will inevitably degrade, and someone will inevitably build a better detector. One suspects the real innovation isn’t in the protocol itself, but in generating yet another layer of abstraction for future engineers to debug.

Ultimately, this work serves as a reminder that quantum security isn’t about solving problems, but about raising the bar for attackers. And that bar, predictably, will always fall. Everything new is just the old thing with worse documentation, and a slightly different set of impossible requirements.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.16489.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Enshrouded: Giant Critter Scales Location

- All Carcadia Burn ECHO Log Locations in Borderlands 4

- All Shrine Climb Locations in Ghost of Yotei

- Top 10 Must-Watch Isekai Anime on Crunchyroll Revealed!

- Best ARs in BF6

- Keeping Agents in Check: A New Framework for Safe Multi-Agent Systems

- All 6 Psalm Cylinder Locations in Silksong

- Best Total Conversion Mods For HOI4

- Poppy Playtime 5: Battery Locations & Locker Code for Huggy Escape Room

- Top 8 UFC 5 Perks Every Fighter Should Use

2026-02-19 09:40