Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have developed a novel construction of error-correcting codes that significantly reduces data overhead while maintaining resilience against deletions.

This paper presents redundancy-optimal (1,1)-criss-cross deletion correcting codes with explicit and efficient encoding/decoding algorithms, achieving a constant gap to theoretical limits.

Achieving robust data storage and retrieval in the face of complex data loss patterns remains a significant challenge in modern information theory. This is addressed in ‘Redundancy-Optimal Constructions of $(1,1)$-Criss-Cross Deletion Correcting Codes with Efficient Encoding/Decoding Algorithms’, which introduces a novel construction of $(1,1)$-criss-cross deletion correcting codes with explicit encoding and decoding algorithms achieving near-optimal redundancy of 2n + 2\log_q n + \mathcal{O}(1). The proposed codes, applicable for n \ge 11 and q \ge 3, boast \mathcal{O}(n^2) complexity, offering a practical balance between performance and efficiency. Could this construction pave the way for more resilient data storage systems in applications ranging from DNA-based storage to advanced memory technologies?

The Inherent Vulnerability of Dense Data Storage

Contemporary data storage systems increasingly depend on arranging data in high-density arrays – think of vast grids of information. While this approach maximizes storage capacity, it introduces a critical vulnerability: localized data loss through deletions. Unlike random errors where individual bits might flip, deletions manifest as entire blocks of data vanishing. This poses a significant challenge because the very structure of these dense arrays means a single physical failure can wipe out a substantial, contiguous section of stored information. The problem is exacerbated by the shrinking size of storage cells; as they become smaller and more numerous, the probability of a localized event causing complete data loss within a small area dramatically increases, demanding innovative strategies for data protection beyond traditional error correction methods.

Conventional error correction codes are fundamentally designed to combat random bit flips-the spontaneous alteration of individual data points-and perform admirably in such scenarios. However, the architecture of modern, high-density data storage introduces a distinctly different failure mode: localized deletions, where entire blocks of data vanish due to physical degradation or media failure. These deletions manifest as correlated errors, creating patterns of loss that traditional codes, optimized for independence, struggle to address effectively. The grid-like structure of two-dimensional arrays exacerbates this issue; a single physical defect can wipe out an entire row or column, overwhelming the capabilities of codes designed to handle scattered, isolated errors. Consequently, a disproportionately large overhead – more redundant data – is often required to achieve the same level of reliability, hindering storage efficiency and increasing costs.

Maintaining data integrity in modern storage systems demands a shift in error correction strategies, moving beyond codes designed to recover from random bit flips to those capable of addressing data deletions. Unlike the unpredictable nature of bit errors, deletions manifest as complete loss of data blocks, a pattern particularly problematic in the increasingly dense storage arrays used today. Conventional codes, optimized for detecting and correcting scattered errors, often prove inadequate when faced with these larger, localized losses. Consequently, research focuses on developing robust codes-often leveraging techniques like erasure coding and Reed-Solomon codes-specifically tailored to reconstruct data even when substantial portions are entirely missing. This proactive approach is crucial, as the reliability of these systems hinges not simply on detecting errors, but on the ability to fully recover lost information in the face of predictable, yet potentially catastrophic, deletion events.

A Codified Solution to Intersecting Data Loss

The Criss-Cross Deletion Code provides a mechanism for constructing codes capable of correcting deletion patterns in two-dimensional arrays where elements are removed along both rows and columns, potentially intersecting. This is achieved by encoding data in a manner that allows reconstruction even with the loss of complete rows or columns, or combinations thereof. The code is specifically designed to address the challenge of data loss arising from these intersecting deletion patterns, which are distinct from simple row or column failures addressed by traditional error correction methods. The resulting code enables reliable data recovery in scenarios where such criss-cross deletions are likely, such as in storage systems or data transmission protocols.

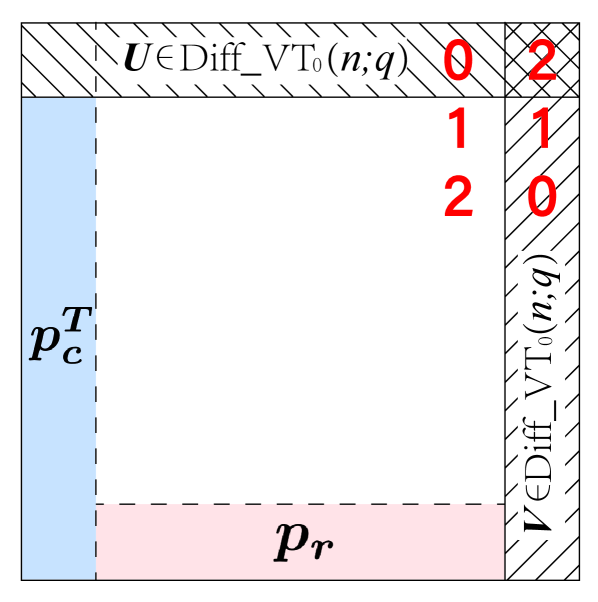

The Criss-Cross Deletion Code improves construction efficiency by utilizing pre-existing one-dimensional error-correcting codes as fundamental components. Specifically, codes like the DifferentialVTCode are employed as building blocks, reducing the computational overhead associated with designing a completely novel two-dimensional error correction scheme. This approach allows the code to inherit the established error-correcting capabilities of the one-dimensional codes while extending them to handle two-dimensional deletion errors; the performance characteristics are directly tied to the properties of the underlying one-dimensional code used in its construction.

The Criss-Cross Deletion Code achieves two-dimensional error correction by strategically combining multiple instances of a one-dimensional error-correcting code. Specifically, data is encoded across both rows and columns, with each row and column employing a distinct instance of the base one-dimensional code – such as the DifferentialVTCode. This arrangement ensures that a deletion affecting a single row or column can be corrected by the corresponding one-dimensional code, while criss-cross deletions – those impacting multiple rows and columns – are addressed through the redundant encoding across both dimensions. The key to this approach is the interleaving of data, allowing the code to differentiate between single-dimensional failures and the more complex criss-cross patterns.

Optimizing for Efficiency: Run Length Limits and Explicit Encoding

Code redundancy directly impacts both the efficiency and reliability of data transmission and storage. It refers to the addition of extra data bits that do not represent the original information but allow for the detection and correction of errors introduced during the process. While increasing redundancy enhances error correction capabilities and thus improves reliability, it simultaneously decreases the effective data rate and increases storage requirements. Therefore, optimizing code performance necessitates a careful balance: minimizing redundancy to maximize efficiency while maintaining a sufficient level to ensure acceptable reliability given the anticipated error rates of the transmission channel or storage medium. The optimal level of redundancy is determined by factors such as the desired bit error rate, the characteristics of the noise, and the computational cost of encoding and decoding.

The Criss-Cross Deletion (CCD) code’s performance is directly enhanced by the Run Length Limited (RLL) constraint. This constraint mandates that no two adjacent symbols can be identical, preventing the formation of long sequences of the same value. By enforcing symbol transitions, the RLL constraint reduces the search space during the decoding process. This simplification translates to lower computational complexity and, consequently, improved decoding efficiency, particularly in scenarios requiring real-time data recovery or high throughput.

ExplicitEncoding, in the context of data storage and transmission, establishes a clearly defined, step-by-step algorithmic procedure for converting data into a coded format. This contrasts with implicit encoding schemes where the coding rules are not fully specified or are derived from system-level assumptions. The benefit of this approach lies in its facilitation of both implementation and analysis; a precise algorithm allows for direct translation into executable code, and its defined nature simplifies the process of proving properties like error-correction capabilities or performance characteristics. This contrasts with schemes relying on complex or probabilistic methods, and enables rigorous verification and optimization of the encoding/decoding processes.

Approaching Theoretical Limits: Efficiency and Practical Implications

Determining a code’s efficiency hinges on understanding its lower bound redundancy, a theoretical limit representing the minimum amount of extra data required for reliable recovery from erasures or errors. This concept provides a benchmark against which any coding scheme can be measured; a code approaching this lower bound is considered highly efficient, minimizing overhead while maximizing robustness. Specifically, the lower bound dictates the unavoidable cost of redundancy needed to guarantee data reconstruction, and codes exceeding this bound introduce unnecessary complexity and storage requirements. Evaluating a code’s performance relative to its lower bound redundancy allows researchers to definitively assess its practical value and potential for optimization, guiding the development of more efficient and scalable data storage and transmission systems.

The Criss-Cross Deletion Code demonstrates a compelling level of efficiency, achieving an encoder redundancy of 2n + 2log_q(n) + O(1). This performance is significant because it nears the theoretical lower bounds of data encoding; the code operates within a constant gap of optimal efficiency. Essentially, the amount of extra data required for error correction scales linearly with the data size (n), with a manageable logarithmic increase related to the size of the symbol alphabet (q). This near-optimality suggests the code provides a robust and resource-conscious solution for data storage and transmission, minimizing redundancy while maintaining a high degree of reliability – a crucial balance in modern data management systems.

The practical utility of the Criss-Cross Deletion Code is underscored by its computational efficiency, despite the inherent complexities of modern data storage and retrieval. While achieving near-optimal redundancy, the algorithms designed for encoding data into this format, decoding it for use, and recovering lost information all exhibit a time complexity of O(n^2). This means the processing time grows proportionally to the square of the data size, n. Although more sophisticated algorithms exist for certain data structures, O(n^2) represents a reasonable balance between computational cost and the benefits of robust data protection, making the code suitable for implementation in a variety of real-world applications where data integrity is paramount and moderate data sizes are expected.

The pursuit of redundancy-optimal codes, as detailed in this construction of (1,1)-criss-cross deletion correcting codes, mirrors a fundamental principle of mathematical elegance. It’s not merely about achieving functionality, but about doing so with the minimal necessary complexity. Ada Lovelace keenly observed, “That brain of mine is something more than merely mortal; as time will show.” This echoes the spirit of seeking the most efficient, provable solution – a code operating at the boundary of what’s possible, where every element serves a demonstrable purpose. The explicit encoding and decoding algorithms presented aren’t simply tools for correction; they are the manifestation of a logically sound, and therefore beautiful, invariant.

What Lies Ahead?

The presented constructions, while achieving optimal redundancy within a constant factor for (1,1)-criss-cross deletion correcting codes, do not represent a final resolution. The elegance of a provably correct algorithm, rather than merely an empirically ‘working’ one, remains paramount. Future work should rigorously examine the adaptability of these techniques to the (r,s) generalizations-a challenge that will undoubtedly reveal the inherent limitations of explicit constructions. A truly satisfying solution would move beyond mere existence proofs and demonstrate a systematic method for generating codes with quantifiable properties-a feat currently obscured by the ad-hoc nature of the designs.

The efficiency of encoding and decoding, while addressed, invites further scrutiny. Current approaches, while functional, operate with complexities that belie the underlying mathematical simplicity. A deeper investigation into differential VT codes and their relation to other error-correcting paradigms may unlock more streamlined algorithms – algorithms that prioritize mathematical purity over pragmatic optimization. To believe that these codes represent the apex of deletion correction would be a display of unwarranted optimism; they are merely a stepping stone.

The field should not rest content with merely improving existing bounds. A fundamental question remains: are there inherent limits to the efficiency of error correction itself? A formal articulation of these limits, coupled with proofs of their necessity, would be a contribution of lasting significance – a testament to the power of mathematical reasoning over empirical observation.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.13548.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Enshrouded: Giant Critter Scales Location

- All Carcadia Burn ECHO Log Locations in Borderlands 4

- All Shrine Climb Locations in Ghost of Yotei

- Best ARs in BF6

- Best Finishers In WWE 2K25

- Top 8 UFC 5 Perks Every Fighter Should Use

- Top 10 Must-Watch Isekai Anime on Crunchyroll Revealed!

- Scopper’s Observation Haki Outshines Shanks’ Future Sight!

- Poppy Playtime 5: Battery Locations & Locker Code for Huggy Escape Room

- How to Unlock & Visit Town Square in Cookie Run: Kingdom

2026-02-18 05:05