Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new coding scheme offers robust data recovery even when information is broken into arbitrary pieces and some are irretrievably lost.

This review details (t,s)-Break-Resilient Codes, a novel approach to data storage and transmission that overcomes limitations of traditional error correction methods in adversarial environments.

Conventional error correction often falters when data is both fragmented and partially lost-a growing concern for modern data storage and transmission. This paper introduces a unifying framework, termed ‘Break-Resilient Codes with Loss Tolerance,’ to address these challenges via a novel code family, $(t,s)$-BRCs, which guarantee reliable decoding even with arbitrary codeword fragmentation and the complete loss of up to $s$ fragments. These codes establish theoretical bounds on necessary redundancy and offer explicit constructions approaching those limits, generalizing both break-resilient and deletion codes. Will this approach pave the way for more robust and efficient data storage solutions in increasingly unreliable environments?

The Fragility of Data: A Foundation of Imperfection

Conventional data transmission protocols are built on the premise of complete message delivery, a scenario rarely mirrored in practical applications. Network congestion, signal interference, and physical storage limitations frequently result in data packets arriving fragmented, corrupted, or lost altogether. This inherent vulnerability extends beyond mere technical glitches; intentional disruption through malicious attacks can deliberately break down data into unusable pieces. Consequently, systems designed for reliable communication and long-term data preservation must contend with the constant possibility of incomplete information, demanding innovative approaches to ensure data integrity despite fragmentation and loss. The expectation of a perfect, unbroken signal represents an idealized case, while robust data handling requires codes and protocols capable of gracefully managing the realities of imperfect transmission and storage.

The fundamental assumption of complete data transmission underpinning much of modern communication and storage systems frequently clashes with reality. Network congestion, physical damage to storage media, or even deliberate interference can introduce fragmentation – breaking data into scattered pieces – or complete erasures. Consequently, ensuring reliable data handling necessitates the development of error-correcting codes that are demonstrably robust against such breaks and losses. These codes don’t simply verify data integrity; they actively reconstruct missing or corrupted portions, allowing for seamless operation even in compromised environments. The sophistication of these codes is continually challenged by increasing data volumes and the growing prevalence of adversarial attacks designed to deliberately fragment data and disrupt communication, driving innovation in areas like erasure coding and fountain codes to provide increasingly resilient solutions.

Current data reconstruction techniques, while effective against random loss or corruption, frequently falter when confronted with deliberately fragmented data. These methods often rely on statistical assumptions about the nature of data loss – that errors are distributed randomly – which malicious actors can exploit by strategically breaking up messages in ways designed to maximize decoding failures. Adversarial fragmentation doesn’t simply remove information; it actively shapes the remaining pieces to mislead reconstruction algorithms. This presents a critical vulnerability, as systems relying on these codes can be compromised not through overwhelming data loss, but through carefully orchestrated, targeted disruption, highlighting the necessity for codes explicitly designed to resist such intelligent attacks.

The increasing prevalence of data transmission across unreliable networks and storage in compromised environments necessitates a paradigm shift in error correction coding. Traditional approaches, designed for random errors, falter when confronted with intentional fragmentation or malicious alteration of data packets. Consequently, research is heavily focused on developing codes that prioritize reconstruction, not merely error detection. These codes must be capable of accurately rebuilding the original data from a potentially sparse and corrupted set of fragments, even if a significant portion has been deliberately removed or modified. This resilience isn’t simply about maintaining data integrity; it’s about ensuring continued functionality and trust in systems operating under adversarial conditions, demanding codes that exhibit a robust ability to recover information from incomplete or compromised sources – a capability becoming increasingly paramount in fields ranging from secure communication to distributed data storage.

Introducing the (t, s)-BRC: A Code Forged in Resilience

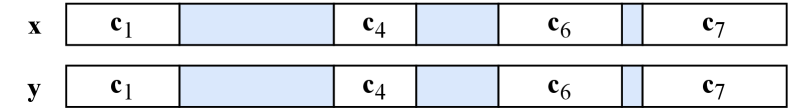

The (t, s)-Break Resilient Code (BRC) is a forward error correction scheme engineered to maintain data integrity despite both fragmentation and data loss. Specifically, a valid (t, s)-BRC encoding guarantees reconstruction of the original data even when the encoded message is split into up to ‘t’ separate fragments-referred to as ‘breaks’-and simultaneously suffers the loss of up to ‘s’ individual bits. This dual tolerance for breaks and bit errors distinguishes it from traditional error correction codes, offering increased robustness in scenarios involving both physical fragmentation and transmission errors. The level of resilience is directly determined by the parameters ‘t’ and ‘s’ chosen during the encoding process; higher values provide greater fault tolerance at the cost of increased redundancy.

The (t, s)-BRC achieves data reconstruction from fragmented data through the incorporation of redundancy. This redundancy isn’t arbitrary; its complexity is formally defined as O(t log²n + s log n), where ‘n’ represents the size of the original data, ‘t’ denotes the number of tolerated breaks (or fragments), and ‘s’ represents the maximum number of lost bits. This logarithmic scaling of redundancy with data size ensures efficient encoding, even for large datasets, while providing the necessary information to recover the original data despite fragmentation and bit loss. The design prioritizes minimizing redundancy while maintaining the specified levels of break and bit error tolerance.

The construction of a valid (t, s)-Break Resilient Code (BRC) necessitates the use of a ‘valid string’ as a foundational element. This ‘valid string’ is a pre-defined sequence possessing specific properties that enable the decoding process to correctly identify and reconstruct lost or corrupted data fragments. Specifically, the string must adhere to constraints regarding its length and the permissible combinations of characters or symbols it contains; deviations from these constraints invalidate the code. The properties of the valid string directly influence the code’s ability to tolerate up to ‘t’ breaks and ‘s’ bit losses, as the decoding algorithm relies on recognizing patterns within this string to determine the original data. Improper construction or selection of the valid string will compromise the resilience and reliability of the (t, s)-BRC.

The (t, s)-BRC offers a framework for reliable communication by maintaining data integrity despite transmission errors or data loss common in hostile or unreliable environments. These environments, which include scenarios like deep space communication, wireless networks with interference, and storage systems prone to failure, often introduce breaks in data streams or bit corruption. The (t, s)-BRC mitigates these issues through redundant encoding, allowing reconstruction of the original data even with up to ‘t’ breaks and ‘s’ lost bits. This resilience is achieved via a construction process that utilizes ‘valid strings’ and maintains a redundancy level of O(t log²n + s log n), ensuring a quantifiable level of data protection against environmental disruptions.

Decoding the Mechanics: Reconstructing Order from Chaos

Encoding is the process of converting an original message into a codeword by adding redundant information. This redundancy is not superfluous; it is deliberately introduced to facilitate both error detection and correction during transmission or storage. The amount of redundancy is determined by the desired level of resilience; a higher degree of redundancy allows for the correction of more errors, but also increases the overall data size. The core principle relies on creating a mathematical relationship between the original message and the codeword, such that deviations from this relationship – indicative of errors – can be identified and resolved using algorithms at the decoding stage. This process ensures that even if portions of the codeword are lost or corrupted, the original message can be accurately reconstructed.

Message fragmentation, common in network transmission and storage, necessitates a mechanism for accurate reassembly. Markers, generated using a mutually uncorrelated code, serve this purpose by uniquely identifying individual segments of the encoded message. This uncorrelated property ensures minimal overlap or ambiguity between marker sequences, reducing the probability of misidentification during reassembly. These markers are appended to or embedded within each segment, providing positional context even if segments arrive out of order or are lost. The use of a code-based approach, rather than simple sequential numbering, provides robustness against errors and allows for detection of missing or corrupted markers, enhancing the reliability of the reassembly process.

Decoding, the process of retrieving the original message, relies on the redundancy intentionally introduced during encoding. This redundancy manifests as extra data, allowing the decoder to identify and correct errors introduced during transmission or storage. Checksums, calculated from segments of the codeword, provide a baseline for verifying data integrity; discrepancies between the calculated checksum and the received checksum indicate corruption. The decoder uses algorithms to locate and correct errors based on the degree of redundancy and the error-correcting capabilities of the employed code; more redundancy allows for correction of a greater number of errors, but increases bandwidth requirements.

The (t, s)-BRC, similar to Reed-Solomon decoding, achieves error correction by transforming received data into a polynomial form and evaluating it at multiple points. This process involves calculating syndromes, which represent discrepancies between the received data and the expected polynomial values. Non-zero syndromes indicate errors. A locator polynomial is then constructed to identify the locations of these errors within the codeword. By determining the roots of the locator polynomial, the error positions are pinpointed, allowing for correction and reconstruction of the original message. The degree of the locator polynomial, and therefore the number of correctable errors, is directly related to the parameters (t, s) defining the BRC scheme.

The Power of Distinctiveness: Building Resilience from Within

The foundation of reliable data reconstruction lies in the BB-Distinct property, a seemingly simple requirement with profound implications for data integrity. This property dictates that every substring within a valid information string must be unique; repetition is strictly forbidden. This constraint isn’t merely an academic exercise, but a critical safeguard against ambiguity during the decoding process. Without unique substrings, the decoder could misinterpret fragmented data, incorrectly assembling pieces and yielding a corrupted result. By enforcing this distinctiveness, the system guarantees that each fragment contributes uniquely to the final reconstruction, enabling accurate recovery even when faced with data loss or deliberate interference. Essentially, the BB-Distinct property transforms the information string into a self-identifying code, ensuring that the decoder can confidently and correctly piece together the original message.

The BB-Distinct property provides a critical mechanism for data recovery, enabling the accurate reconstruction of fragmented information even when faced with deliberate disruption. This resilience stems from the unique identification of substrings within a valid data string; the decoder isn’t simply looking for matching pieces, but verifying that each fragment’s signature is demonstrably distinct from all others. This characteristic is paramount in adversarial environments, where malicious actors might attempt to inject false data or manipulate existing fragments to compromise the integrity of the reconstructed message. By demanding this level of uniqueness, the system effectively creates a self-checking mechanism, ensuring that only legitimate data contributes to the final, decoded output and mitigating the impact of potential interference.

The effectiveness of this data encoding lies in the deliberate construction of permissible strings, effectively building resilience against both unintentional data corruption and malicious tampering. This isn’t simply about error correction; it’s about proactively designing a system where the probability of successfully recovering the original information string, denoted as ‘z’, approaches certainty. Specifically, the methodology ensures a success probability of 1 - 1/poly(m), where ‘m’ represents a key parameter influencing the code’s robustness. This high probability isn’t achieved through redundant repetition, but through a unique structural property embedded within the valid strings themselves, making it exceedingly difficult for attackers to introduce errors that would lead to a false, yet seemingly valid, decoded message. The result is a data encoding scheme that offers a quantifiable level of security and data integrity, exceeding the capabilities of traditional error-correcting codes.

The deliberate attention to fundamental data properties, such as the BB-Distinct characteristic, significantly broadens the potential applications of (t, s)-BRC beyond theoretical constructs. This isn’t merely about error correction; it’s about building inherently secure data storage and transmission systems. By focusing on these properties during the encoding process, (t, s)-BRC becomes viable in environments where data integrity is paramount – think secure financial transactions, critical infrastructure control systems, or long-term archival storage where bit rot and malicious tampering pose constant threats. The ability to guarantee a high probability of successful decoding, even with substantial data corruption, transforms (t, s)-BRC from a coding scheme into a robust foundation for applications demanding unwavering data security and reliability, ensuring information remains both accessible and trustworthy over extended periods or across hostile networks.

The pursuit of (t,s)-BRC, as detailed in the study, mirrors a fundamental principle of efficient design: minimizing complexity to maximize resilience. This aligns perfectly with John von Neumann’s assertion: “There is no substitute for elegance.” The elegance here isn’t aesthetic, but structural; the code achieves robust data recovery – even amidst adversarial fragmentation and loss – by prioritizing a streamlined approach to error correction. It’s a testament to the power of paring down to essential components, a surgical removal of redundancy that doesn’t compromise integrity. Intuition suggests this focus on core principles is the most reliable compiler for truly robust systems.

The Road Ahead

The introduction of (t,s)-BRC does not, of course, solve the problem of data resilience. It merely shifts the locus of complexity. The current formulation presupposes a known fragmentation pattern, a condition rarely met in genuinely adversarial environments. Future work must address the challenge of blind recovery – reconstructing data from fragments where even the original partitioning is unknown. This is not an engineering problem so much as an exercise in Bayesian humility – acknowledging what one does not know, and building systems that gracefully accept that ignorance.

A natural extension lies in the exploration of resource allocation. The parameters ‘t’ and ‘s’ represent a trade-off between redundancy and efficiency. Existing analyses tend toward optimizing for maximum recovery with minimal overhead, but a more nuanced approach might prioritize selective recovery – identifying and reconstructing the most critical data fragments first. Such a strategy demands a rigorous definition of ‘criticality’ – a surprisingly elusive concept in information theory.

Ultimately, the true measure of this, or any, coding scheme will not be its theoretical capacity, but its practical cost. The elegance of a solution on paper is meaningless if it demands computational resources that outweigh the value of the data it protects. Simplicity, therefore, remains the ultimate goal – not as an aesthetic preference, but as a necessary condition for sustainability.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.14623.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- EUR USD PREDICTION

- Epic Games Store Free Games for November 6 Are Great for the Busy Holiday Season

- How to Unlock & Upgrade Hobbies in Heartopia

- Battlefield 6 Open Beta Anti-Cheat Has Weird Issue on PC

- Sony Shuts Down PlayStation Stars Loyalty Program

- The Mandalorian & Grogu Hits A Worrying Star Wars Snag Ahead Of Its Release

- ARC Raiders Player Loses 100k Worth of Items in the Worst Possible Way

- Unveiling the Eye Patch Pirate: Oda’s Big Reveal in One Piece’s Elbaf Arc!

- TRX PREDICTION. TRX cryptocurrency

- Xbox Game Pass September Wave 1 Revealed

2026-01-22 10:27