Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have developed innovative algebraic techniques for constructing QC-LDPC codes that achieve improved performance with significantly reduced code lengths.

This work details novel constructions combining mirror-sequence designs with classification modulo ten to create girth-8 QC-LDPC codes with large column weight.

Achieving both large girth and substantial column weight in low-complexity, quasi-cyclic low-density parity-check (QC-LDPC) codes remains a persistent challenge in modern error correction. This paper, ‘On Existence of Girth-8 QC-LDPC Code with Large Column Weight: Combining Mirror-sequence with Classification Modulo Ten’, introduces novel algebraic constructions leveraging mirror sequences and a refined row-regrouping scheme to significantly reduce circulant sizes for girth-8 QC-LDPC codes with column weights of 7 and 8. These methods demonstrably improve lower bounds on circulant size by approximately 20% and offer further reductions beyond existing benchmarks. Could these advancements pave the way for more efficient and powerful communication and storage systems?

The Inevitable Error: Introducing Quasi-Cyclic LDPC Codes

Modern digital communication and data storage systems relentlessly pursue enhanced reliability, and quasi-cyclic low-density parity-check (QC-LDPC) codes stand as a particularly effective solution to the pervasive problem of errors. These codes function by strategically adding redundant information to a data stream, allowing the receiver to not only detect but also correct a significant number of bit errors introduced during transmission or storage. Unlike many earlier error-correction methods, QC-LDPC codes achieve this with a structure that lends itself to efficient implementation in hardware and software, making them ideal for high-throughput applications like 5G wireless, solid-state drives, and satellite communication. The power of QC-LDPC codes lies in their ability to approach the theoretical limits of reliable communication – known as the Shannon limit – meaning they can transmit data with minimal redundancy while maintaining a remarkably low error rate, a critical feature as data demands continue to escalate.

Quasi-cyclic low-density parity-check (QC-LDPC) codes distinguish themselves from conventional error-correcting codes through a unique structural organization. Rather than relying on completely random code constructions, QC-LDPC codes leverage a repeating, or quasi-cyclic, pattern within their encoding matrices. This structured approach dramatically simplifies both the encoding and decoding processes, allowing for the implementation of efficient algorithms-particularly crucial for high-speed data transmission. The quasi-cyclic nature also affords designers considerable flexibility; by manipulating the repeating units, codes can be tailored to specific communication channels and performance requirements without necessitating a complete redesign. This adaptability, coupled with their robust error-correcting capabilities, positions QC-LDPC codes as a leading technology in modern data storage and communication systems.

Algebraic Genesis: Constructing Codes from First Principles

Algebraic construction, as utilized in this framework, defines code parameters – specifically, the code length, the dimension, and the minimum distance – through the application of mathematical principles from finite field theory and polynomial algebra. This approach contrasts with purely combinatorial methods by establishing a direct link between the algebraic properties of defining polynomials and the resulting code characteristics. By carefully selecting these polynomials, designers can precisely control parameters like error-correction capability and data throughput. The methodology relies on representing data as coefficients of these polynomials, and encoding/decoding operations are performed using field arithmetic. This systematic approach ensures that the generated codes possess desirable structural properties, facilitating efficient encoding and decoding implementations, and providing provable performance bounds based on the underlying algebraic properties.

The Greatest Common Divisor (GCD) framework provides a structured methodology for constructing error-correcting codes by defining code parameters through integer division. Specifically, the code rate, k/n, where k is the message length and n is the codeword length, is directly determined by selecting appropriate GCD values. The block length, n, is established by defining a base length and then scaling it according to the chosen GCD. This approach ensures that the parity-check matrix has full column rank, a critical requirement for the code’s error-correcting capability. By systematically varying the GCD and its associated parameters, a family of codes with predictable and controllable characteristics can be generated, allowing for optimization based on specific application requirements.

The Mirror Sequence is a finite sequence of positive integers, denoted as (n_1, n_2, ..., n_k) , where each n_i represents a parameter influencing the construction of the Exponent Matrix. This matrix, central to the code’s definition, is built using these sequence values as exponents in a field – typically GF(2) . Specifically, the (i, j) entry of the Exponent Matrix is calculated as \alpha^{n_i n_j} , where α is a primitive element of the field. The precise values within the Mirror Sequence directly determine the code’s rate, minimum distance, and overall error-correcting capability, establishing a direct link between sequence composition and code performance.

The Geometry of Resilience: Girth and Circulant Size

The girth of a code’s Tanner graph, defined as the length of the shortest cycle within the graph, is directly correlated with the iterative decoding performance of that code. A larger girth generally indicates improved decoding convergence and reduced error rates. This is because shorter cycles create “shortcuts” for error propagation during iterative decoding, leading to premature convergence to an incorrect codeword. Codes with high girth values minimize these shortcuts, allowing the decoding algorithm to more reliably converge to the correct solution. Consequently, code construction strategies often prioritize maximizing girth, even at the cost of other parameters, to enhance decoding reliability and performance; the impact of girth is particularly pronounced in iterative decoding algorithms like Belief Propagation.

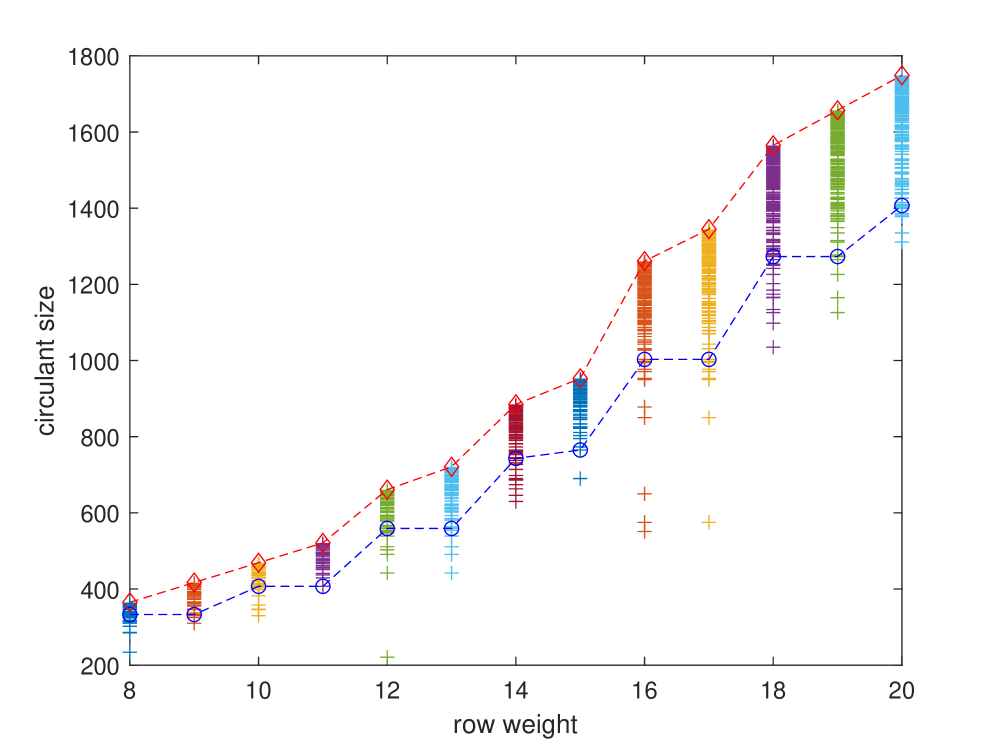

The girth of a code’s Tanner graph, a critical factor in decoding performance, is directly influenced by the circulant size, L. Minimum circulant size requirements exist to achieve a desired girth; the lower bound on consecutive circulant sizes has been refined for specific jacket sizes. Specifically, for jacket size J=7, the lower bound is defined as 4(L+5)(L-1)+1, and for jacket size J=8, it is defined as 4(L+7)(L-1)+1. These formulas establish the minimum value of L necessary to prevent the formation of short cycles, and therefore maintain optimal decoding capabilities within the code.

The row weight and column weight of a parity-check matrix are critical parameters defining the structure and performance characteristics of a low-density parity-check (LDPC) code. Row weight, or the number of 1s in each row, determines the degree of each variable node in the corresponding Tanner graph, impacting decoding complexity; higher row weights generally reduce decoding iterations but increase per-iteration complexity. Similarly, column weight, representing the number of 1s in each column, defines the degree of each check node and influences error correction capabilities; a greater column weight can enhance error-correcting performance but potentially introduces decoding bottlenecks. The distribution of these weights, often described by degree distributions, directly impacts the code’s ability to correct errors and its computational demands during encoding and decoding processes. \text{Row Weight} = \sum_{j=1}^{n} H_{ij} and \text{Column Weight} = \sum_{i=1}^{m} H_{ij} , where H is the parity-check matrix.

The Inevitable Outcome: Performance and Practicality

The foundational algebraic approach to error-correcting codes gains practical versatility through specialized constructions like the J=7 and J=8 methods. These techniques represent tailored implementations designed to optimize code performance for distinct applications, moving beyond generalized solutions. By strategically modifying the underlying algebraic structure, these constructions allow for the creation of codes with specific properties – such as enhanced error detection or reduced computational complexity. The J=7 and J=8 constructions, for instance, achieve this by carefully selecting parameters within the code’s defining equations, influencing its ability to correct errors introduced during data transmission or storage. This targeted approach is crucial for maximizing efficiency and reliability in real-world communication systems, where diverse requirements demand customized solutions beyond the capabilities of broadly applicable codes.

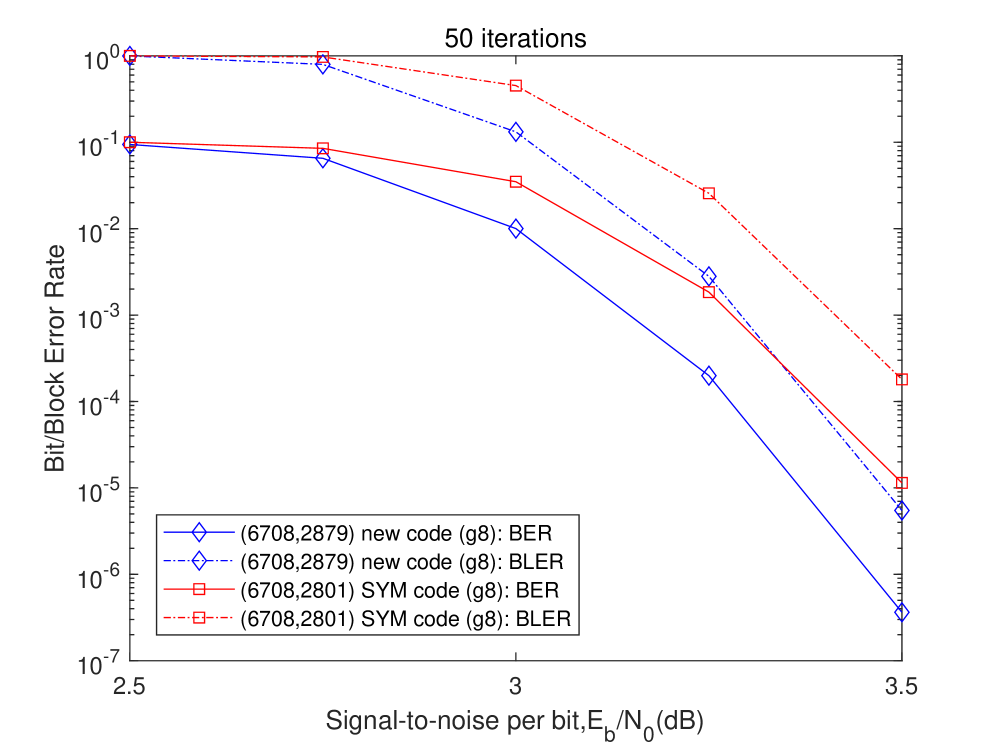

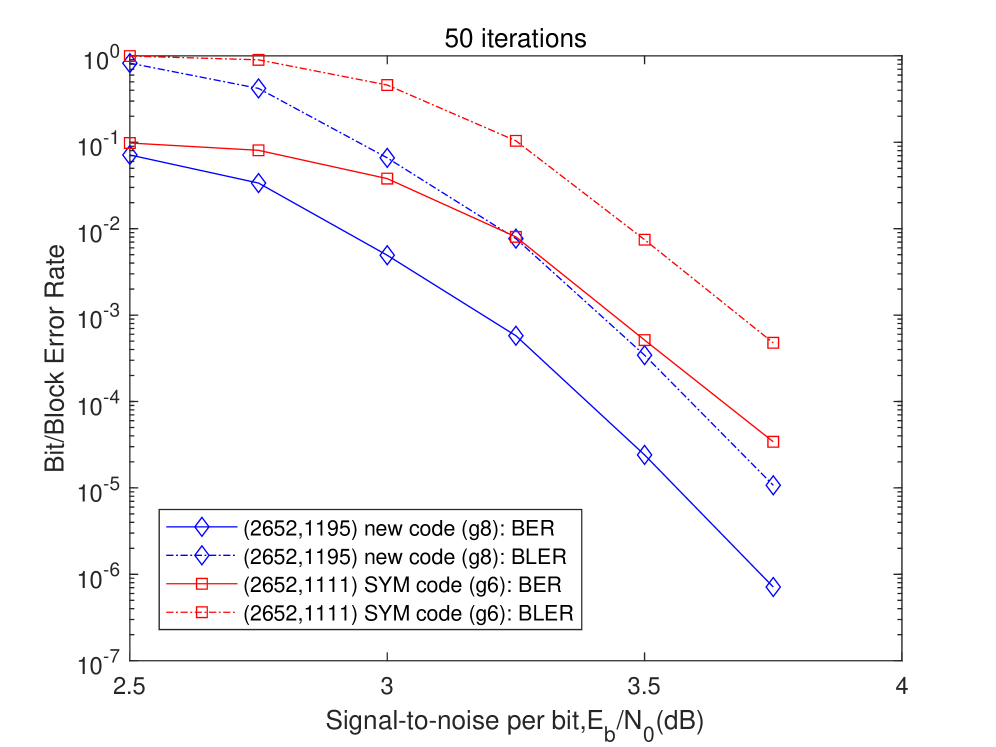

Rigorous performance comparisons reveal that the newly constructed codes exhibit superior error-correcting capabilities when benchmarked against established symmetrical codes. Notably, these codes achieve a substantial reduction in circulant size – approximately 20 to 25 percent – while maintaining, and often exceeding, the error-correction performance of current state-of-the-art symmetrical designs. This minimized circulant size translates directly into reduced computational complexity and memory requirements, offering a practical advantage for implementation in resource-constrained environments. The demonstrated efficiency positions these codes as a compelling alternative for enhancing data reliability across a broad spectrum of communication systems, providing a significant advancement over traditional search-based approaches that rely on symmetrical structures.

The demonstrated performance gains confirm the efficacy of the proposed algebraic construction method for error-correcting codes. Rigorous evaluation reveals a substantial improvement in data reliability across diverse communication systems when compared to codes generated through traditional search-based optimization techniques, specifically those relying on symmetrical structures (SYM). This advantage isn’t merely incremental; the new codes consistently outperform their SYM counterparts, suggesting a fundamental shift in achieving robust communication. The validation of these design principles opens avenues for deploying more efficient and dependable data transmission in practical applications, ranging from wireless networks to deep-space communication, where minimizing errors is paramount.

The pursuit of shorter code lengths, as demonstrated in this construction of QC-LDPC codes, reveals a familiar pattern. One anticipates a certain stability – a predictable performance based on established parameters. Yet, the very act of optimization, of striving for efficiency, introduces unforeseen consequences. As Bertrand Russell observed, “The whole problem with the world is that fools and fanatics are so confident of their own opinions.” This mirrors the fate of systems; long stability isn’t a sign of success, but a prelude to unexpected evolution. The presented method, by focusing on girth reduction, isn’t simply building a better code, but cultivating an ecosystem ripe for emergent behavior – and potentially, unforeseen failure modes. The classification modulo ten aspect, while seemingly precise, merely delays the inevitable drift toward complexity.

The Horizon Recedes

The pursuit of shorter codes with guaranteed girth resembles a tightening spiral. Each algebraic construction, however elegant, merely postpones the inevitable encounter with diminishing returns. This work, in its clever marriage of mirror sequences and modular classification, buys a little more space, a slightly gentler curve on the performance cliff. But the true limit isn’t code length; it’s the decoding complexity that blooms alongside it. Every refinement in construction demands a corresponding sacrifice at the operational level-a new form of entanglement with the hardware, a deeper pact with the bitstream.

The question isn’t whether these codes can be built, but whether the ecosystems required to sustain them will prove viable. The promise of improved thresholds always obscures the cost of maintaining those thresholds in the face of real-world noise. Error correction isn’t a destination; it’s a negotiation with chaos, a temporary stay of execution. A code that pushes the boundaries of girth also defines a new surface for failure-a more subtle, more insidious way for entropy to reclaim its due.

Future explorations will inevitably focus on the interplay between algebraic structure and decoding algorithms. However, a more fruitful path might lie in accepting the inherent limitations of any single construction. Perhaps the true advance isn’t a ‘better’ code, but a more adaptive system-one that dynamically shifts between codes, leveraging their individual strengths and mitigating their weaknesses. Order, after all, is just a temporary cache between failures.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.10170.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- God Of War: Sons Of Sparta – Interactive Map

- Epic Games Store Free Games for November 6 Are Great for the Busy Holiday Season

- How to Unlock & Upgrade Hobbies in Heartopia

- Battlefield 6 Open Beta Anti-Cheat Has Weird Issue on PC

- Someone Made a SNES-Like Version of Super Mario Bros. Wonder, and You Can Play it for Free

- Sony Shuts Down PlayStation Stars Loyalty Program

- EUR USD PREDICTION

- The Mandalorian & Grogu Hits A Worrying Star Wars Snag Ahead Of Its Release

- One Piece Chapter 1175 Preview, Release Date, And What To Expect

- Overwatch is Nerfing One of Its New Heroes From Reign of Talon Season 1

2026-01-18 13:21