Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have developed ZOR filters, a novel approach to representing sets of data that offers a compelling trade-off between speed and memory usage.

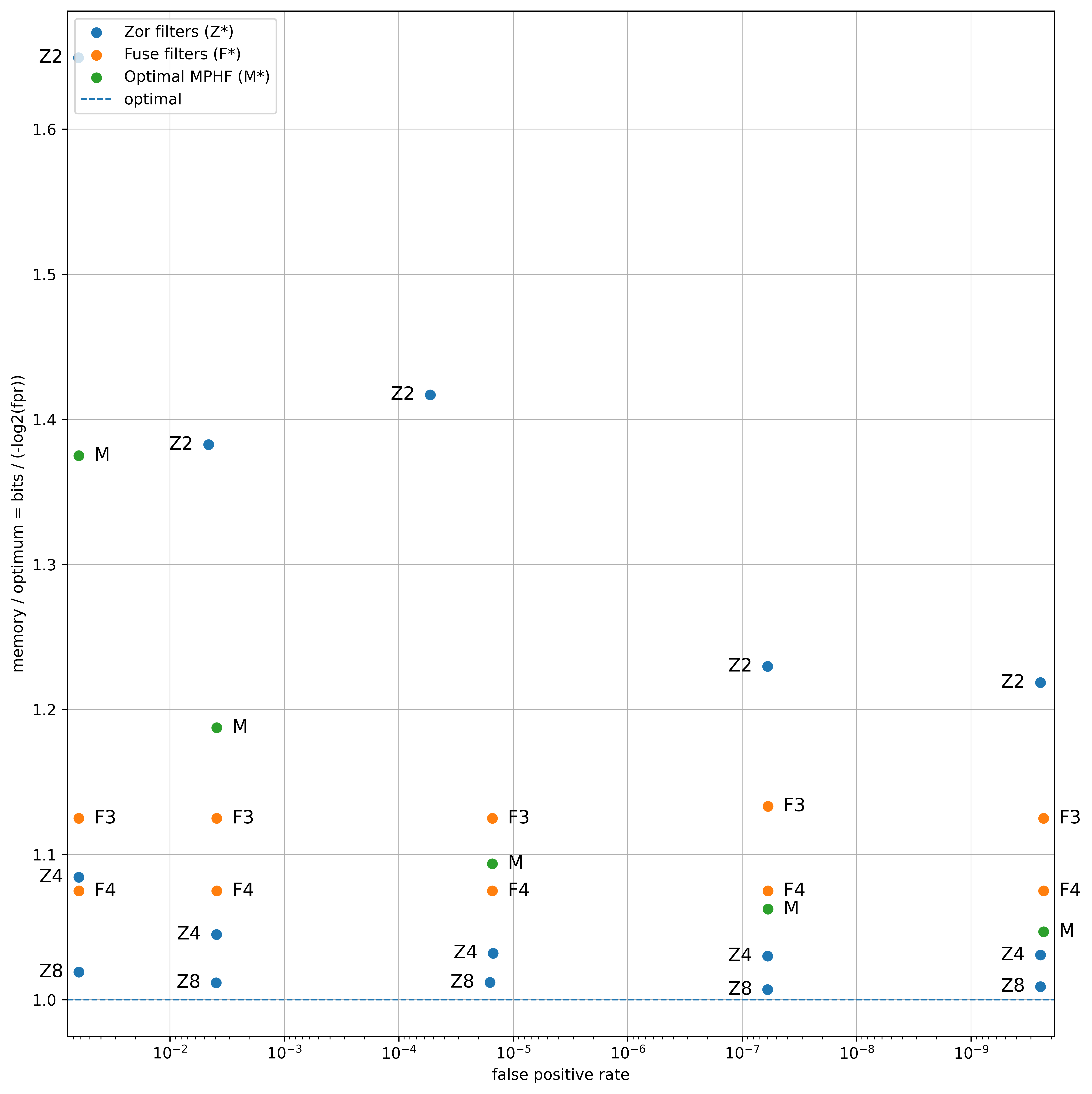

ZOR filters build on XOR and fuse filters to achieve near-optimal memory efficiency by intelligently handling a small subset of keys with an auxiliary structure.

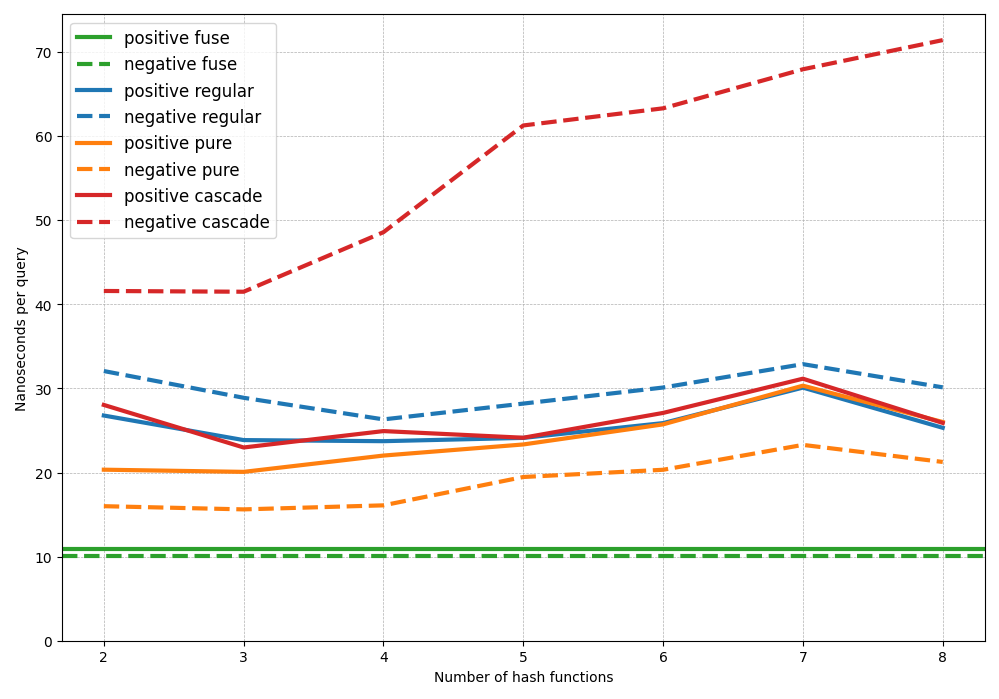

Approximate membership filters offer efficient set representation but often rely on probabilistic construction methods that complicate deterministic builds. This paper introduces ‘ZOR filters: fast and smaller than fuse filters’, a novel design that deterministically extends XOR and fuse filters while maintaining comparable query performance. ZOR achieves this by abandoning a negligible fraction of keys-less than 1% for moderate configurations-and storing them in a compact auxiliary structure, resulting in near-optimal memory overhead within 1\% of the information-theoretic lower bound. Can this deterministic approach, and the resulting optimisation challenges in construction speed, unlock broader applications for these filters in latency-sensitive systems?

The Inevitable Compromise of Set Membership

Conventional set representation in computer science frequently leverages hashing to swiftly determine membership – whether a specific element resides within the set. However, this approach isn’t without its limitations; the fundamental nature of hash functions means different inputs can, and often do, produce the same output, a phenomenon known as a collision. These collisions manifest as false positives, incorrectly indicating an element’s presence when it is, in fact, absent from the set. While techniques exist to mitigate collision rates – such as employing larger hash tables or more sophisticated hash functions – they invariably increase space requirements or computational overhead. Consequently, the accuracy of membership determination is intrinsically tied to the probability of collisions, creating a persistent challenge for applications demanding absolute certainty or operating with exceptionally large datasets where even a small false positive rate becomes significant.

A fundamental limitation in managing large datasets arises from the unavoidable trade-off between memory usage and the potential for inaccurate results. Techniques relying on probabilistic membership – determining if an element belongs to a set – often prioritize space efficiency by accepting a controlled error rate, known as the false positive rate. While minimizing memory footprint is crucial for data-intensive applications like network monitoring or database query optimization, a higher false positive rate means accepting some degree of inaccuracy. This necessitates careful calibration: reducing the false positive rate demands significantly more memory, while prioritizing space leads to increased errors. Consequently, developers face a constant balancing act, tailoring these filters to meet the specific requirements of their application and acknowledging the inherent compromise between resource consumption and data integrity.

Maintaining data filters in rapidly changing environments presents a significant hurdle for traditional, static approaches to set membership. These conventional filters, built on techniques like Bloom filters, excel at quickly determining if an element is possibly in a set, but struggle to adapt when the set itself is constantly evolving. Inserting new elements isn’t inherently problematic, yet deleting elements-removing the indication that something might be present-is impossible without resetting the entire filter, a computationally expensive operation. This limitation becomes acutely problematic in dynamic datasets, such as network traffic analysis or real-time recommendation systems, where data streams are continuous and the relevance of information changes constantly. Consequently, researchers are actively exploring filter designs that balance the need for efficient membership testing with the capability to accurately reflect insertions and deletions, often at the cost of increased complexity or memory usage.

The Evolution of Filtering Techniques: A Necessary Progression

Bloom Filters operate by utilizing multiple hash functions to map elements to bits in a bit array; a potential element is considered present if all corresponding bits are set. While offering simplicity and space efficiency, this approach inherently introduces false positives – incorrectly identifying an element as present when it is not – with the probability of a false positive increasing as the filter fills. Crucially, standard Bloom Filters do not support deletions; removing an element requires resetting the corresponding bits, which could incorrectly indicate the absence of other elements also mapped to those bits. This limitation stems from the filter’s design, where multiple elements can hash to the same bit positions, making it impossible to distinguish which element should be removed without introducing errors.

Cuckoo and Quotient filters are designed to handle dynamic datasets-those with frequent insertions and deletions-by employing more sophisticated strategies than static filters. Cuckoo filters achieve this through multiple hash tables and a relocation process when collisions occur, while Quotient filters divide the filter space into segments and utilize a quotient-remainder scheme. However, these approaches introduce computational overhead due to the complexity of hash calculations and relocation/segment management. Furthermore, Cuckoo filters can experience instability and performance degradation if the filter becomes too full, leading to cycles in the relocation process. Quotient filters, while generally more stable, can suffer from performance issues related to segment overflows or inefficient lookups if not properly sized and maintained.

Static filter designs, including XOR and Fuse filters, achieve high performance in terms of both speed and space utilization by employing bitwise operations and compact data structures. However, these filters are inherently limited in their ability to handle dynamic datasets; insertions and deletions are not natively supported without rebuilding the entire filter. This inflexibility stems from their reliance on fixed, pre-computed bit patterns derived from the initial dataset. Consequently, any modification to the data necessitates a complete reconstruction of the filter, making them unsuitable for applications requiring frequent updates or evolving data streams.

ZOR Filters: A Deterministic Shift in the Landscape

ZOR Filters address the limitations of traditional Bloom filters by guaranteeing zero false negatives. This is achieved through a dual-layer construction: a primary Bloom filter utilizing XOR hashing for efficient membership testing, coupled with an auxiliary filter that stores a small subset of hash values. During a query, if the primary filter returns a potential membership, the auxiliary filter verifies the existence of the corresponding hash value, thereby confirming true membership and eliminating any possibility of a false negative. The XOR hashing function is crucial as it ensures that collisions are minimized, contributing to the filter’s overall performance and reduced memory usage.

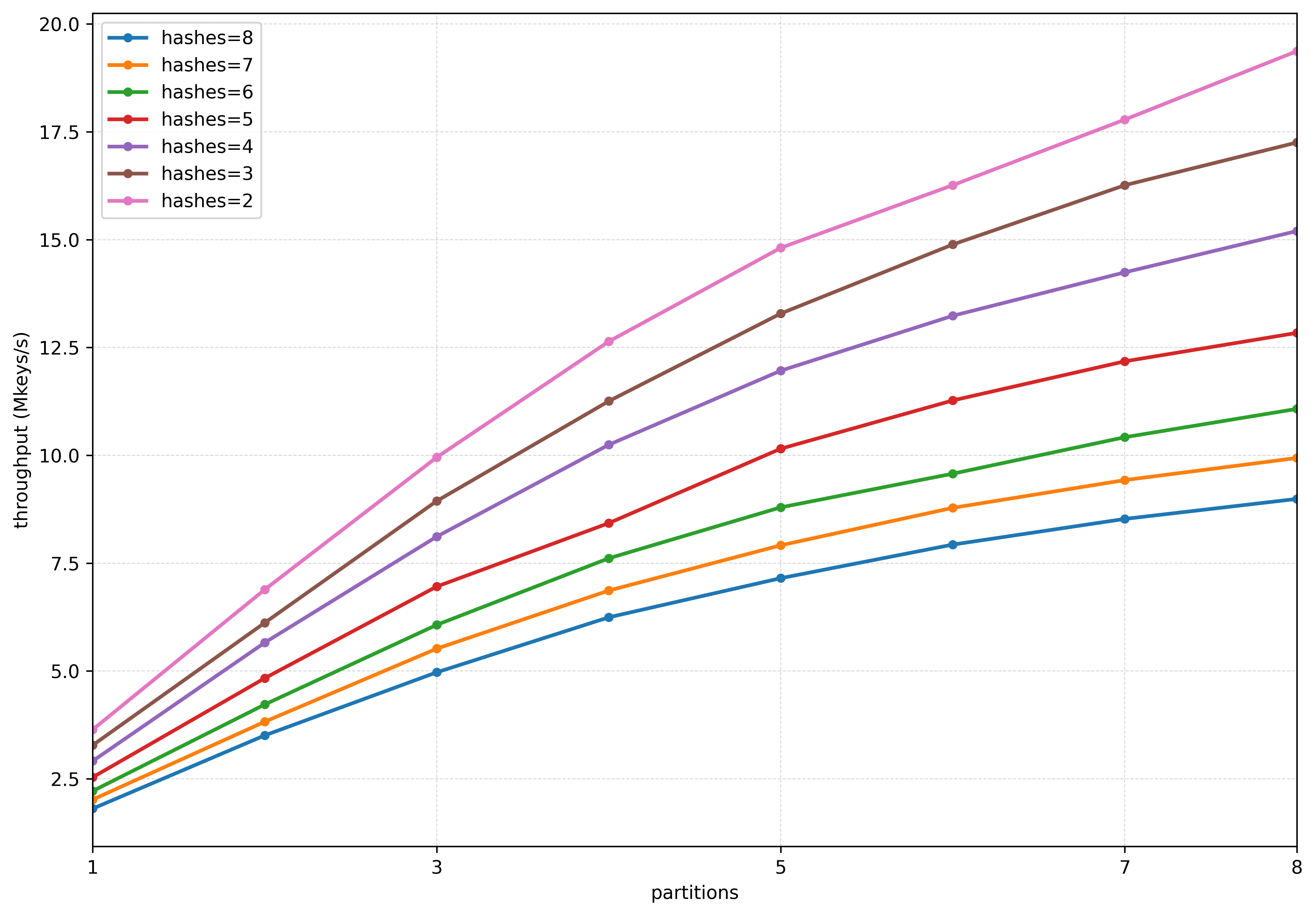

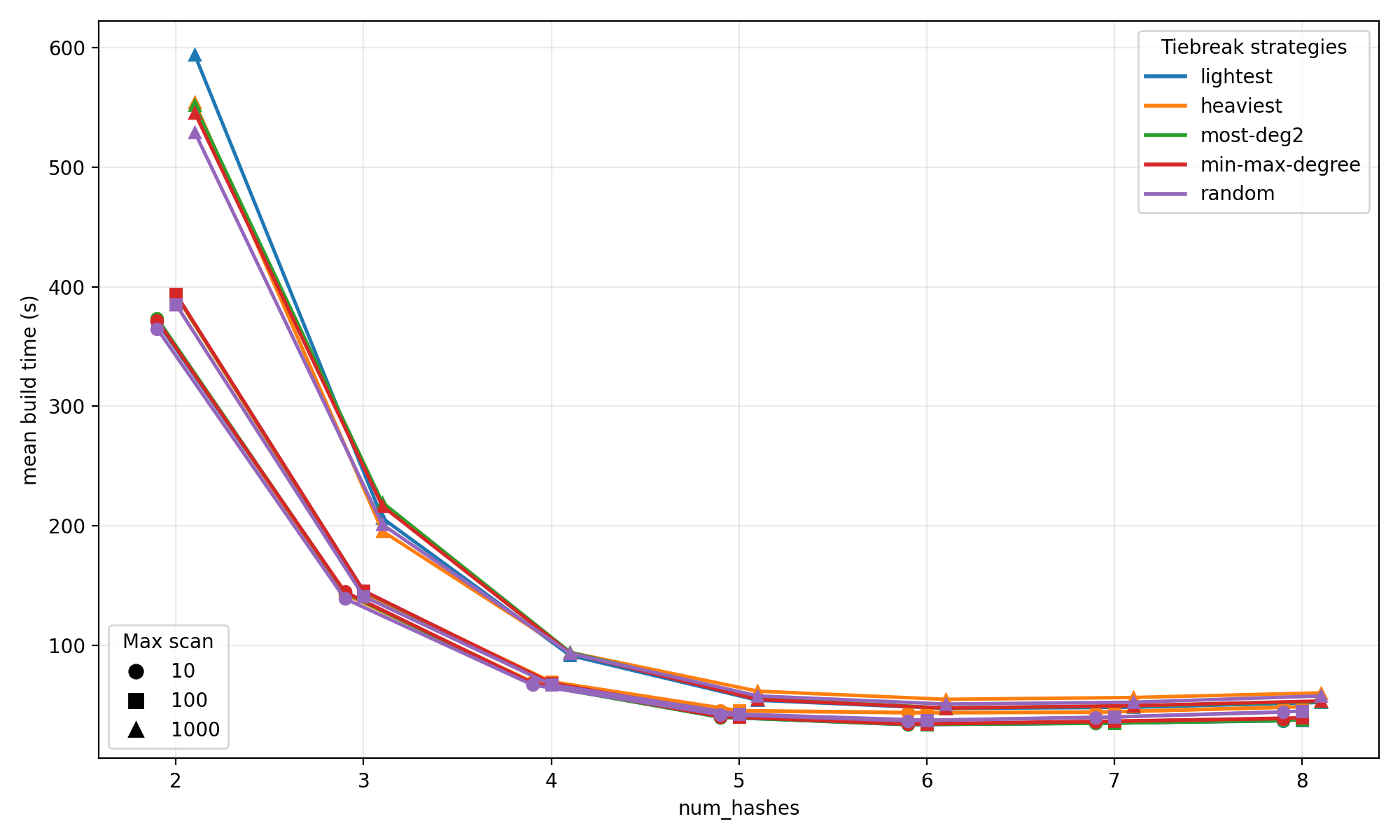

ZOR filters utilize segmented hashing to distribute the hash space across multiple segments, allowing for concurrent construction and query processing. This approach divides the filter into independently manageable partitions, significantly reducing the time required for both building and searching. Parallel construction further accelerates filter creation by assigning each segment to a separate processing unit, effectively scaling with the available hardware resources. The segmentation also minimizes contention and synchronization overhead, contributing to improved performance, particularly with large datasets. This architecture allows ZOR filters to efficiently handle high insertion and query rates, making them suitable for dynamic and high-throughput applications.

ZOR filters demonstrate high memory efficiency by approaching the theoretical minimum storage required for a probabilistic filter. This is achieved through design choices informed by the information-theoretic lower bound on false positive rates. Specifically, ZOR filters maintain an overhead of less than 1% above this established limit, indicating a near-optimal utilization of memory resources. This efficiency is critical for applications demanding large-scale filtering with constrained memory budgets, as it minimizes the storage cost per element tracked while maintaining a predictably low false positive probability.

The Practical Implications: Speed, Efficiency, and Controlled Compromise

ZOR filters balance the demands of storage space and construction speed through a controlled abandonment rate – a deliberate allowance for certain keys to be excluded during the filter’s creation. This approach introduces a small probability of false negatives, but dramatically reduces the time needed to build the filter, particularly for large datasets. Studies demonstrate that an abandonment rate of just 0.4% – achieved with 8-wise filters – provides a compelling trade-off, minimizing the impact on query accuracy while significantly accelerating the filtering process. This carefully calibrated balance ensures ZOR filters remain both efficient and practical for applications requiring rapid data screening, even with limited computational resources.

High query speeds are fundamentally reliant on efficient cache utilization, a principle keenly demonstrated by Fuse filters. These filters prioritize minimizing memory access latency by strategically organizing data to maximize the likelihood of finding requested information within the faster cache memory. Instead of sequentially scanning large datasets, Fuse filters employ techniques that predict data access patterns and pre-fetch relevant information, dramatically reducing the time required to locate and retrieve data. This approach is particularly crucial in scenarios involving frequent queries, where repeated access to the same data can be significantly accelerated by caching. Consequently, the performance gains from optimized cache utilization, as exemplified by Fuse filters, directly translate into faster response times and improved overall system efficiency, making it a cornerstone of high-performance data retrieval systems.

ZOR filters demonstrate remarkable speed and efficiency in data retrieval, achieving a query time of just 100 nanoseconds per key – a crucial metric for high-performance applications. This speed is accomplished through a carefully balanced design that minimizes auxiliary space requirements; the filter utilizes an additional fingerprint size of only F + 8 bits, where ‘F’ represents the size of the main filter’s fingerprint. This compact auxiliary structure allows for rapid verification of key existence without incurring substantial memory overhead, making ZOR filters particularly well-suited for scenarios demanding both speed and space efficiency. The design effectively trades a small increase in fingerprint size for a significant reduction in query latency, offering a practical solution for large-scale data filtering and indexing.

The pursuit of efficient set representation, as detailed in this paper concerning ZOR filters, echoes a fundamental truth about complex systems. It’s not about achieving perfect fidelity-eliminating all false positives-but about intelligently managing tradeoffs. As Donald Davies observed, “Everything connected will someday fall together.” This resonates deeply with the design of ZOR filters; abandoning a small fraction of keys isn’t a failure, but a calculated acceptance of eventual dependency. The auxiliary structure isn’t a patch, but a recognition that even the most elegant system will, over time, succumb to the weight of its connections and require managed degradation. The focus on memory efficiency isn’t about minimizing resources, but about prolonging the inevitable-delaying the moment when the system’s inherent fragility becomes overwhelming.

What Lies Ahead?

The pursuit of ever-tighter set representation, as exemplified by ZOR filters, is not a march toward perfection, but a dance with inevitability. Each optimization-each bit shaved from the false positive rate-simply delays the moment when the structure reveals its inherent limitations. The auxiliary structure, necessary to handle discarded keys, is not a bug, but a prophecy. It signals the fundamental truth that complete set membership, in a finite space, is a transient illusion.

Future work will inevitably focus on scaling these approximate filters. However, true progress lies not in handling larger sets, but in accepting the inherent uncertainty. Rather than striving to minimize false positives, research should explore how to effectively utilize them. What applications can not merely tolerate, but benefit from a controlled degree of imprecision? The real challenge is not building filters that fail less, but systems that gracefully accommodate failure’s inevitable evolution.

The elegance of ZOR filters lies in their deterministic nature, a comforting artifact in an increasingly probabilistic world. Yet, even determinism is merely a local maximum. Long stability is the sign of a hidden disaster, and the very efficiency that defines these filters will ultimately become the vector for unforeseen consequences. The question is not whether they will break, but what unexpected shape the breakage will take.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.03525.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- God Of War: Sons Of Sparta – Interactive Map

- Poppy Playtime Chapter 5: Engineering Workshop Locker Keypad Code Guide

- Poppy Playtime 5: Battery Locations & Locker Code for Huggy Escape Room

- Poppy Playtime Chapter 5: Emoji Keypad Code in Conditioning

- Someone Made a SNES-Like Version of Super Mario Bros. Wonder, and You Can Play it for Free

- Who Is the Information Broker in The Sims 4?

- Why Aave is Making Waves with $1B in Tokenized Assets – You Won’t Believe This!

- One Piece Chapter 1175 Preview, Release Date, And What To Expect

- How to Unlock & Visit Town Square in Cookie Run: Kingdom

- All Kamurocho Locker Keys in Yakuza Kiwami 3

2026-02-05 05:37