Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have developed a method for dramatically reducing the size of large language models without sacrificing performance by strategically preserving key information and reconstructing lost details.

This paper introduces Structured Residual Reconstruction (SRR), a framework for balancing rank budgets to improve low-bit quantization and efficient fine-tuning of transformer models.

Post-training quantization of large language models often suffers accuracy loss due to the discarding of crucial weight information. This paper, ‘Preserve-Then-Quantize: Balancing Rank Budgets for Quantization Error Reconstruction in LLMs’, introduces Structured Residual Reconstruction (SRR), a framework that strategically allocates a limited rank budget by preserving dominant structural information in the original weights before reconstructing quantization error. SRR achieves this by balancing the preservation of top singular subspace components with error reconstruction, leading to improved performance in low-bit quantization and enabling more stable and efficient parameter-efficient fine-tuning. Could this approach unlock even more aggressive quantization levels without sacrificing model capabilities?

The Inevitable Loss: Precision’s Price in Deep Learning

The escalating complexity of deep learning models, particularly within the realm of large language transformers, presents a substantial challenge to computational efficiency. These models, boasting billions – and increasingly, trillions – of parameters, require immense processing power and memory for both training and inference. This demand stems from the need to perform countless matrix multiplications and other operations on high-dimensional data. Consequently, deploying these powerful models on resource-constrained devices – such as mobile phones, embedded systems, or even standard servers – becomes impractical without significant optimization. The sheer scale of these models not only increases energy consumption but also limits accessibility, hindering wider adoption and innovation in artificial intelligence. Addressing this computational burden is therefore critical for democratizing AI and enabling real-world applications beyond the reach of large data centers.

Post-training quantization represents a crucial technique for compressing deep learning models, enabling deployment on resource-constrained devices. However, this compression isn’t without cost; the process inherently introduces quantization error. This error arises from representing the model’s weights and activations with lower precision – for example, transitioning from 32-bit floating-point numbers to 8-bit integers. While reducing model size and accelerating inference, this reduced precision leads to information loss, potentially degrading the model’s accuracy and overall performance. The magnitude of this performance degradation depends on factors like the model architecture, the dataset, and the specific quantization method employed, necessitating careful calibration and potentially further refinement techniques to mitigate the impact of quantization error and maintain acceptable levels of performance.

Reducing the numerical precision of deep learning models – a process known as bit-width reduction – presents a significant hurdle to practical deployment. While decreasing the number of bits used to represent weights and activations can dramatically shrink model size and accelerate computation, it often comes at the cost of accuracy. This ‘quantization error’ arises because fewer bits limit the granularity with which values can be represented, effectively rounding off information. Even seemingly minor reductions, such as transitioning from 32-bit floating-point to 8-bit integer representations, can lead to substantial performance degradation, particularly in complex models like large language transformers. Consequently, naive bit-width reduction often necessitates extensive retraining or sophisticated calibration techniques to mitigate these losses and maintain acceptable levels of performance, complicating the pathway to efficient and deployable artificial intelligence.

The Ghost in the Machine: Reconstructing Lost Information

Analysis of large transformer models consistently reveals a significant degree of redundancy within their weight matrices, indicating that a substantial portion of the representational capacity can be effectively captured by a lower-dimensional subspace. This manifests as a strong, low-rank signal; specifically, the singular value decomposition (SVD) of these weight matrices demonstrates that a small number of singular values typically account for the majority of the energy, or variance, within the matrix. This implies that the weights are not uniformly distributed across the parameter space but instead exhibit a dominant structure governed by a relatively small set of principal components. The observed low-rank characteristic suggests that many of the original weights can be accurately reconstructed from this reduced representation, providing a basis for effective compression and reconstruction techniques.

Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) is employed to analyze the dominant weight structure within transformer models by decomposing the weight matrices into three constituent matrices: U, Σ, and V^T. The resulting singular values, represented in Σ, reveal the relative importance of each dimension in the original weight matrix; dimensions with significantly larger singular values contribute most to the overall weight structure. By retaining only the top k singular values and their corresponding singular vectors, a low-rank approximation of the original weight matrix is achieved. The difference between the original matrix and its low-rank approximation represents the information lost during this reduction; this difference is then used to construct Low-Rank Correction matrices, which aim to recover the most critical lost information and mitigate the effects of subsequent quantization or compression.

Low-rank correction matrices address quantization error by approximating the lost information resulting from reduced numerical precision. Quantization, the process of mapping a continuous range of values to a discrete set, introduces error; the magnitude of this error is inversely proportional to the number of bits used for representation. By applying a low-rank update – effectively adding a matrix constructed from the dominant singular values of the original weight matrix – the reconstruction process recovers a significant portion of the information discarded during quantization. This is based on the principle that the weight matrices in transformers exhibit a dominant low-rank structure, meaning a substantial portion of their variability can be captured by a relatively small number of singular values and vectors. The correction matrices effectively “fill in” the missing information, minimizing performance degradation associated with lower precision weights.

Preserving the Signal: Structured Residual Reconstruction

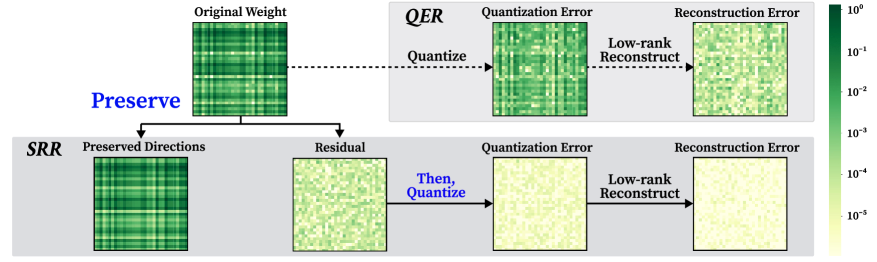

Structured Residual Reconstruction (SRR) differentiates itself from conventional quantization error reconstruction methods by operating on two complementary objectives within a unified framework. Instead of sequentially addressing error reduction after structural damage from quantization, SRR simultaneously preserves salient structural information within the weights while reconstructing the introduced quantization error. This is achieved by decomposing weight updates into a low-rank structural component – designed to maintain the original weight matrix’s inherent properties – and a residual error component that focuses solely on correcting the quantization inaccuracies. By explicitly managing both aspects concurrently, SRR minimizes the trade-off between maintaining model integrity and improving accuracy following post-training quantization (PTQ).

Structured Residual Reconstruction mitigates accuracy loss during quantization by leveraging both low-rank approximations and residual correction. The technique initially decomposes weight matrices into low-rank representations, reducing the number of parameters susceptible to quantization error. Subsequently, residual correction focuses on the difference between the original weights and their low-rank approximations. By quantizing and reconstructing this residual, the method preserves critical high-frequency details often lost during standard quantization, thereby minimizing overall accuracy degradation and enabling more effective model compression.

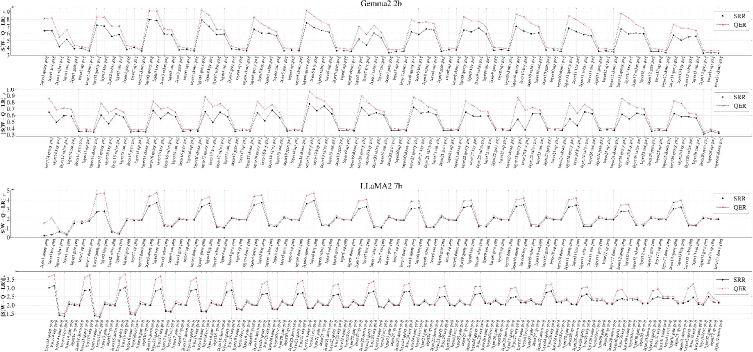

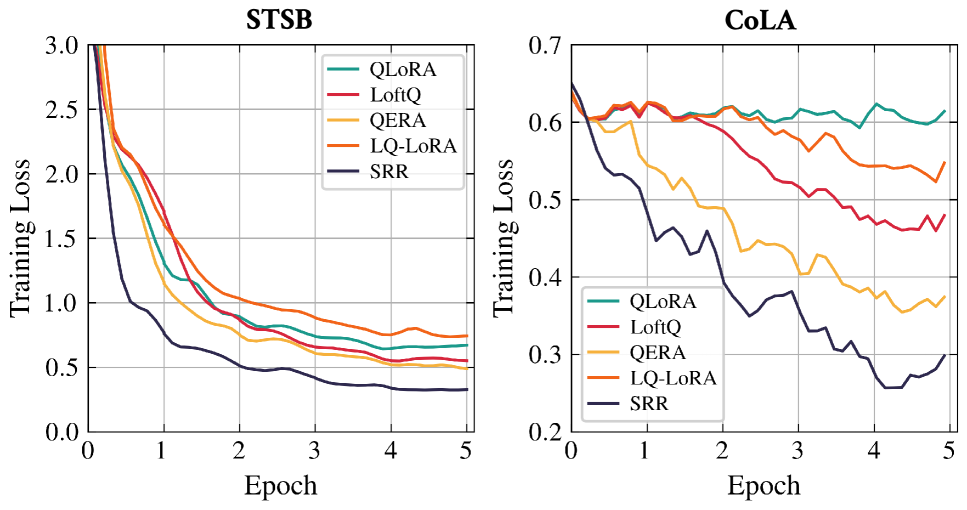

Structured Residual Reconstruction builds upon established Quantization Error Reconstruction (QER) methods by demonstrating significant performance gains. Evaluations on the LLaMA-2 7B model, using Post-Training Quantization (PTQ), indicate a perplexity reduction of up to 27.1% compared to baseline QER techniques. This improvement suggests that explicitly modeling and correcting quantization errors, combined with structural preservation, yields a more accurate and efficient quantized model without substantial accuracy loss.

The Efficient Specialist: Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning

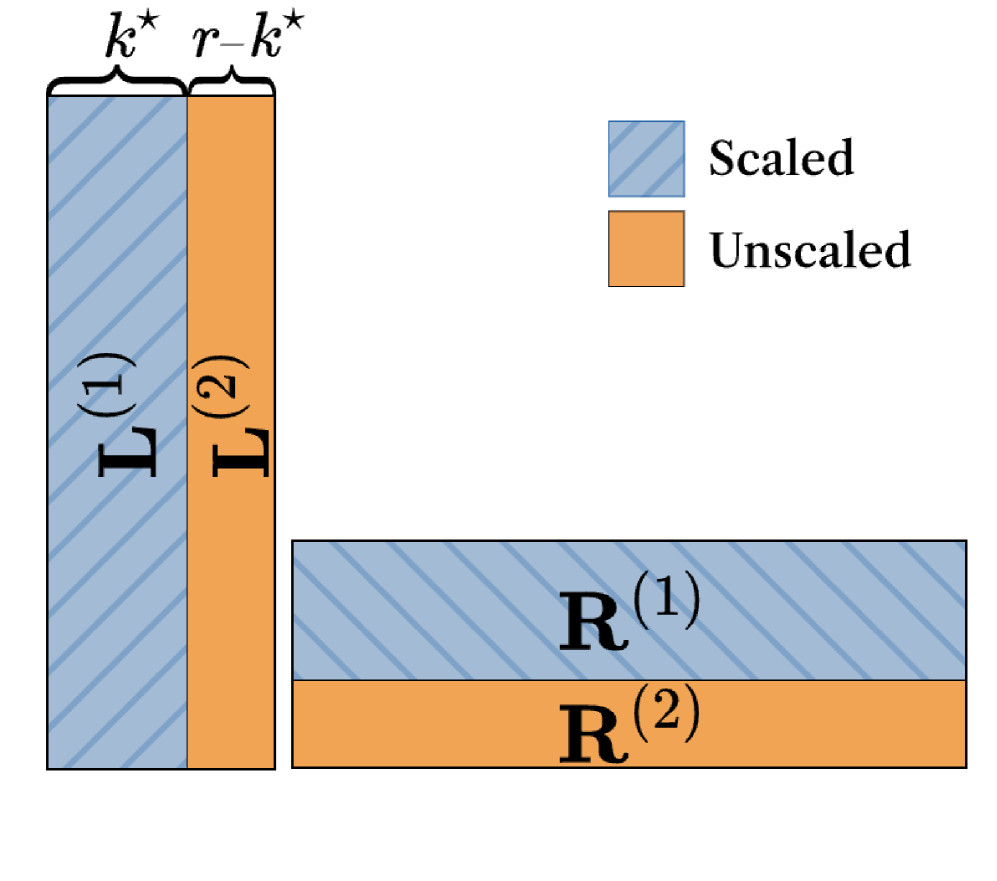

Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) presents a compelling solution for refining pre-trained quantized language models without the substantial computational demands of full fine-tuning. Instead of adjusting all model parameters, LoRA introduces trainable low-rank matrices that represent the updates to the original weights. This drastically reduces the number of parameters needing optimization – often by over 90% – while still achieving comparable performance gains. By focusing updates on a smaller, more manageable set of parameters, LoRA enables efficient adaptation even with limited computational resources, making it particularly suitable for deployment on edge devices or in resource-constrained environments. The technique effectively captures the essential nuances of a new task without altering the core knowledge embedded within the pre-trained model, preserving its general capabilities while specializing it for the target application.

QLoRA and similar techniques address the substantial computational demands of fine-tuning large language models by strategically updating model weights using low-rank matrices. Instead of adjusting all parameters – a process requiring immense memory and processing power – these methods introduce smaller, low-rank matrices that represent the changes to be made. This approach dramatically reduces the number of trainable parameters, allowing for efficient adaptation even on limited hardware. Essentially, the model learns to approximate the necessary weight updates with a significantly compressed representation, preserving performance while minimizing computational cost and memory footprint. This enables the fine-tuning of models with billions of parameters on a single GPU, democratizing access to advanced natural language processing capabilities.

Gradient scaling plays a crucial role in stabilizing and enhancing the accuracy of low-rank adaptation during model fine-tuning. As quantized models are particularly sensitive to the magnitude of weight updates, standard gradient descent can lead to instability or divergence. This technique dynamically adjusts the scale of gradients during backpropagation, preventing excessively large updates that could disrupt the delicate balance within the quantized weights. By carefully controlling the gradient magnitude, the fine-tuning process becomes more robust and reliable, ultimately leading to improved model performance and generalization capabilities, particularly noticeable in scenarios with limited computational resources and stringent quantization requirements.

The integration of Structured Residual Reconstruction with low-rank adaptation techniques yields significant performance enhancements across various language models. Empirical results demonstrate a substantial reduction in perplexity, reaching up to 12.2% when applied to the Gemma-2 2B model. Moreover, zero-shot accuracy benefits are notable, with a 5.9% gain observed on the LLaMA-2 7B model using QPEFT. This approach also extends to complex reasoning tasks; evaluations on the GSM8K dataset reveal a 1.7% improvement in performance when utilizing the LLaMA-3.1 8B model, indicating that Structured Residual Reconstruction effectively refines fine-tuning, boosting both language modeling capabilities and problem-solving abilities.

The pursuit of ever-smaller models, as this paper demonstrates with its Structured Residual Reconstruction (SRR) framework, feels…familiar. It’s always the same story. They’ll call it efficient fine-tuning, but it’s just another way to accrue tech debt. This focus on balancing preservation with reconstruction-carefully managing what gets thrown away and what gets approximated-is a tacit admission that perfect compression is a myth. It’s a temporary reprieve, a delay of the inevitable entropy. As Barbara Liskov once said, “It’s one of the really hard things about programming – that you have to deal with complexity.” Complexity doesn’t disappear; it merely shifts form, hiding in the carefully constructed residuals and gradient scaling. They’ll boast about the reduced bit-width, but someone, somewhere, will inevitably encounter a case where the approximations break down, and it’ll be back to square one. It used to be a simple bash script, now it’s SRR and they’re raising funding.

Where Do We Go From Here?

This ‘Preserve-Then-Quantize’ approach, with its careful balancing of rank budgets and structured residual reconstruction, feels… familiar. It’s a new set of knobs to turn, certainly, but it addresses a problem as old as optimization itself: information loss. The authors manage quantization error a bit better, which buys some performance. But production will inevitably reveal the edge cases, the peculiar inputs where these reconstructed residuals collapse into something resembling noise. It always does.

The real question isn’t whether this improves low-bit quantization – it likely will, for a while. It’s whether this complexity is worth the gain. The tooling around these low-rank adaptation methods is already a mess, and adding another layer of reconstruction feels like building a Rube Goldberg machine to solve a problem a slightly slower computer could have handled. One suspects future work will focus on automating the ‘preservation’ stage, or perhaps simply finding more efficient ways to ignore the errors in the first place.

Ultimately, this feels like a refinement, not a revolution. Another incremental step towards squeezing more performance out of ever-larger models. And, as always, everything new is just the old thing with worse docs.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.02001.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Poppy Playtime Chapter 5: Engineering Workshop Locker Keypad Code Guide

- Jujutsu Kaisen Modulo Chapter 23 Preview: Yuji And Maru End Cursed Spirits

- God Of War: Sons Of Sparta – Interactive Map

- Poppy Playtime 5: Battery Locations & Locker Code for Huggy Escape Room

- Who Is the Information Broker in The Sims 4?

- 8 One Piece Characters Who Deserved Better Endings

- Pressure Hand Locker Code in Poppy Playtime: Chapter 5

- Poppy Playtime Chapter 5: Emoji Keypad Code in Conditioning

- Why Aave is Making Waves with $1B in Tokenized Assets – You Won’t Believe This!

- Engineering Power Puzzle Solution in Poppy Playtime: Chapter 5

2026-02-03 11:41