Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have successfully integrated spin-orbit coupling into a powerful quantum Monte Carlo method, paving the way for more accurate modeling of complex materials.

This work details the implementation of spin-orbit coupling within the phaseless auxiliary-field quantum Monte Carlo method for improved electronic structure calculations.

Accurate modeling of materials containing heavy elements remains a significant challenge in electronic structure theory due to strong relativistic effects. This work presents a successful implementation of spin-orbit coupling within the phaseless auxiliary-field quantum Monte Carlo (pw-AFQMC) method, utilizing fully-relativistic pseudopotentials to capture both electronic correlation and spin-orbit interactions. Demonstrating improved accuracy for systems like I2 and Pb, this advancement enables reliable first-principles calculations on strongly correlated materials-particularly those containing heavy atoms. Will this approach unlock new insights into the behavior of complex materials under extreme conditions and accelerate the design of novel functional materials?

The Limits of Approximation: Seeking Accuracy in Materials Modeling

Density Functional Theory (DFT) remains a foundational technique in materials science, prized for its computational efficiency in simulating the electronic structure of materials. However, its widespread application is tempered by inherent limitations when addressing strongly correlated systems – materials where electron-electron interactions are particularly potent. The core of DFT relies on approximations to the complex exchange-correlation functional, which accounts for these interactions. These approximations, while enabling practical calculations, can lead to significant inaccuracies in predicting ground-state properties like magnetic ordering, band gaps, and even the stability of certain materials. Consequently, despite its successes, DFT often falters when confronted with systems exhibiting strong electron correlation, necessitating the development and implementation of more advanced computational methods to accurately capture their behavior and unlock their full potential.

The predictive power of materials science relies heavily on accurately determining a material’s ground-state properties – its most stable energy and electron configuration. However, approximations within Density Functional Theory (DFT) can introduce significant errors in calculating these fundamental characteristics, particularly in materials where electron interactions are strong. These inaccuracies aren’t merely academic; they directly impede the rational design of novel materials. A flawed prediction of a ground state can lead to the pursuit of compounds that are theoretically promising but experimentally unstable, or conversely, the dismissal of potentially groundbreaking materials. Consequently, the limitations in ground-state property prediction represent a substantial bottleneck in fields ranging from superconductivity and energy storage to catalysis and quantum computing, necessitating the development of more robust computational approaches.

The limitations of Density Functional Theory (DFT) in describing strongly correlated materials necessitate the application of more advanced many-body techniques to achieve accurate predictions. Methods such as Dynamical Mean-Field Theory (DMFT), Quantum Monte Carlo, and coupled cluster approaches directly address the complex electron-electron interactions that DFT approximates, offering a path towards reliable modeling of exotic quantum phenomena. These computationally intensive methods, while demanding, provide crucial insights into material properties-including magnetism, superconductivity, and metal-insulator transitions-that are inaccessible through standard DFT calculations. By explicitly accounting for electron correlation, researchers can gain a deeper understanding of material behavior and accelerate the discovery of novel materials with tailored functionalities, pushing the boundaries of materials science and condensed matter physics.

Phaseless AFQMC: A First-Principles Approach to Quantum Systems

Phaseless Auxiliary Field Quantum Monte Carlo (AFQMC) is a first-principles, or ab initio, computational method used to determine the ground-state properties of many-body quantum systems. Unlike methods reliant on empirical parameters, Phaseless AFQMC directly addresses the time-independent Schrödinger equation H|\Psi\rangle = E|\Psi\rangle through stochastic sampling. This approach systematically improves with increasing computational resources, allowing for controlled convergence to the exact ground state energy and other observables. The method’s accuracy is not fundamentally limited by approximations to the many-body wave function, but rather by statistical error and the practical limitations of the simulation.

Phaseless Auxiliary-Field Quantum Monte Carlo (AFQMC) employs a trial wave function, \Psi_T, to constrain the stochastic sampling of many-body configurations, improving efficiency and reducing variance. This trial wave function, typically a Slater determinant or Jastrow-Slater determinant, guides the walkers in configuration space. The computationally demanding electron-electron interaction term is addressed via the Hubbard-Stratonovich transformation, which decomposes the interaction into a sum of single-body terms. This transformation allows for efficient sampling by expressing the two-body interaction as a series of one-body operators, effectively mapping the many-body problem onto a set of single-particle problems that can be evaluated stochastically.

Finite Size Correction (FSC) techniques are essential in Auxiliary Function Quantum Monte Carlo (AFQMC) calculations due to the limitations of simulating infinite systems on finite computational resources. These techniques address systematic errors arising from the use of periodic boundary conditions or fixed-size simulation boxes, which can artificially alter the energy and other properties of the system. FSC typically involves extrapolating results obtained from simulations of varying system sizes to the thermodynamic limit – the behavior of the system as its size approaches infinity. Common methods include fitting the energy or other observables to a function of system size, such as E(N) = E_{\in fty} + aN^{-1} + bN^{-2}, where E_{\in fty} is the extrapolated energy in the thermodynamic limit, and ‘a’ and ‘b’ are fitting parameters. Accurate determination of these parameters and careful consideration of the functional form are critical for minimizing the error in the extrapolated results and achieving reliable predictions of material properties.

The Foundation of Accurate Simulations: Basis Sets and Pseudopotentials

Plane-wave basis sets utilize Fourier transforms to represent electronic wavefunctions as a superposition of plane waves, e^{i\mathbf{k}\cdot\mathbf{r}}, where \mathbf{k} is a wavevector and \mathbf{r} is the position vector. This approach is particularly well-suited for crystalline solids and extended systems due to its inherent compatibility with periodic boundary conditions. The periodicity of the crystal lattice directly corresponds to the reciprocal space defined by the plane waves, allowing for an efficient and accurate description of Bloch’s theorem. By expanding the wavefunctions in a set of plane waves defined on a uniform grid in reciprocal space, the computational effort is streamlined, and the implementation of periodic boundary conditions becomes straightforward, minimizing artificial interactions between periodic images of the system.

Norm-Conserving Vanderbilt (NCV) pseudopotentials address the computational challenge of treating core electrons in electronic structure calculations. By replacing the strong, rapidly oscillating potential near the nucleus with a smoother, weaker potential, NCV pseudopotentials significantly reduce the number of plane waves required to accurately represent the electronic wavefunction, thereby lowering computational cost. The “norm-conserving” aspect ensures that the shape of the valence electron wavefunctions outside the core region remains virtually identical to that of the all-electron calculation, preserving crucial physical properties. This is achieved through a non-local potential that incorporates the scattering properties of the core electrons, effectively mimicking their influence on the valence electrons without explicitly calculating their behavior. Accurate description of this core-valence interaction is critical for reliable prediction of material properties like cohesive energies, lattice parameters, and elastic constants.

ONCV (Oppenheimer-Nakai-Carrington-Vanderbilt) pseudopotentials represent a significant advancement in electronic structure calculations due to their enhanced transferability across different materials. Unlike earlier pseudopotentials which often required re-optimization for each element or chemical environment, ONCV potentials are designed to maintain accuracy when applied to a wider range of compositions and bonding scenarios. This is achieved through a construction method that rigorously conserves the norm of the wavefunction, minimizing spurious effects arising from the core-electron reduction. Specifically, calculations performed on materials such as Indium Phosphide (InP) and Lead (Pb) demonstrate the reliability of ONCV pseudopotentials in predicting accurate electronic band structures and other material properties, offering a robust framework for materials discovery and characterization.

Expanding Predictive Power: Incorporating Spin-Orbit Coupling

Spin-orbit coupling, a consequence of Einstein’s theory of relativity, dramatically impacts the behavior of electrons in atoms containing heavy elements like lead. This effect arises from the interaction between an electron’s spin and its orbital motion, becoming more pronounced as the atomic nucleus’s charge increases-and thus, for heavier elements. Consequently, the electronic and magnetic properties of these materials are significantly altered; traditional calculations that ignore spin-orbit coupling can yield inaccurate predictions. The effect doesn’t simply add a small correction; it fundamentally changes the electronic structure, influencing everything from chemical bonding to optical properties and magnetic ordering in materials containing these heavier atoms.

Accurately modeling the behavior of electrons in heavier elements necessitates a sophisticated treatment of their intrinsic angular momentum, or spin. Consequently, phaseless Auxiliary Field Quantum Monte Carlo (AFQMC) calculations, when applied to systems exhibiting significant relativistic effects, require the implementation of Two-Component Spinor Wave Functions. These functions move beyond the typical single-component description by explicitly incorporating the electron’s spin degree of freedom, effectively treating spin-up and spin-down states as independent entities. This approach is crucial because spin and orbital angular momentum become coupled through the spin-orbit interaction, influencing a material’s electronic structure and magnetic properties, and ultimately leading to more accurate predictions of its behavior – a marked improvement over calculations which treat electron spin as an implicit property.

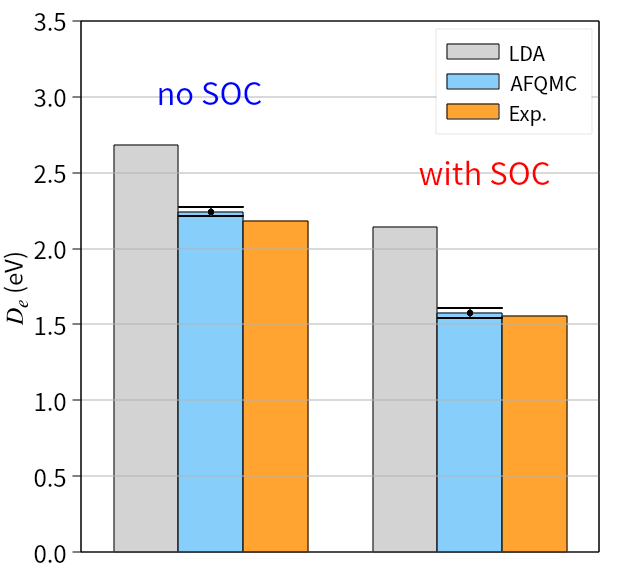

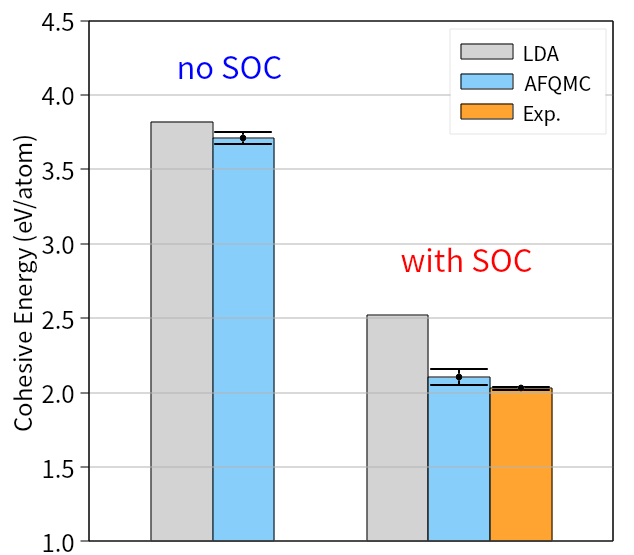

Calculations incorporating spin-orbit coupling have notably refined the accuracy of predicting material properties, as evidenced by improvements in modeling lead and iodine-based compounds. Specifically, the calculated cohesive energy of lead demonstrates a significant reduction in discrepancy – 1.61(7) eV – when spin-orbit coupling is included, indicating a more realistic representation of its electronic structure. Furthermore, the predicted dissociation energy of iodine molecules aligns with experimental observations to within a statistical uncertainty of just 0.06(3) eV, validating the method’s capability to accurately describe chemical bonding and molecular behavior where relativistic effects are prominent. These results highlight the importance of accounting for spin-orbit coupling in achieving reliable computational predictions for heavier elements and complex materials.

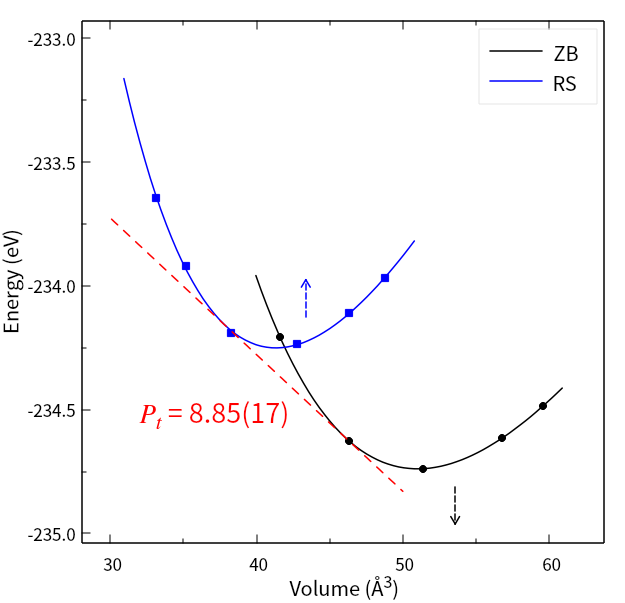

Calculations on Indium Phosphide (InP) reveal a transition pressure remarkably consistent with results obtained using the Generalized Gradient Approximation (GGA), a widely employed density functional theory method. However, the phaseless AFQMC calculations slightly underestimate the experimentally determined transition pressure. This discrepancy is attributed to residual finite-size effects inherent in the computational approach; simulating infinite materials with finite computational cells introduces subtle inaccuracies. Despite this minor deviation, the close agreement between the phaseless AFQMC calculations and experimental data demonstrates the method’s potential for accurately predicting the behavior of materials under extreme pressure, even when dealing with the complexities introduced by relativistic effects and finite system sizes.

The advancement detailed in this work-a phaseless auxiliary-field quantum Monte Carlo method incorporating spin-orbit coupling-underscores a critical responsibility inherent in computational materials science. An engineer is responsible not only for system function, but its consequences; this method’s enhanced accuracy for materials with heavy elements directly addresses limitations in existing density functional theory calculations. As Stephen Hawking observed, “Intelligence is the ability to adapt to any environment.” This principle resonates deeply; the presented method represents an adaptation of existing computational techniques, broadening the scope of materials research and allowing for more robust investigations into strongly correlated systems. Ethics must scale with technology, and this improvement offers a pathway towards more reliable and insightful predictions in the realm of materials discovery.

Beyond the Accuracy: Charting a Course Forward

The successful incorporation of spin-orbit coupling into phaseless auxiliary-field quantum Monte Carlo-a technical achievement, certainly-risks becoming another increment in a relentless pursuit of precision divorced from purpose. Someone will call it AI-driven materials discovery, and someone will get hurt when the resulting “optimized” alloy fails in unforeseen ways. The demonstrated improvements in accuracy for systems containing heavy elements are valuable, but the true challenge lies not in calculating what is, but in understanding what could be, and the ethical implications of that potential. Efficiency without morality is illusion.

Future work will undoubtedly focus on scaling these calculations to even larger systems, and on further refining the underlying pseudopotentials. However, a more pressing need is to address the fundamental limitations of the method itself – the inherent approximations that, even with increased computational power, will always mediate access to true material behavior. The field must confront the question of systematic error, and move beyond merely benchmarking against density functional theory – a framework already known to have its own, significant failings.

Perhaps the most valuable direction lies in coupling this method not with materials databases, but with frameworks for assessing risk and uncertainty. To model not just the electron, but the consequences. The pursuit of computational mastery should not overshadow the necessity of responsible innovation, a recognition that the most accurate calculation is meaningless without a clear understanding of its limitations, and the values encoded within it.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.11866.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- EUR USD PREDICTION

- Epic Games Store Free Games for November 6 Are Great for the Busy Holiday Season

- How to Unlock & Upgrade Hobbies in Heartopia

- Battlefield 6 Open Beta Anti-Cheat Has Weird Issue on PC

- Sony Shuts Down PlayStation Stars Loyalty Program

- TRX PREDICTION. TRX cryptocurrency

- The Mandalorian & Grogu Hits A Worrying Star Wars Snag Ahead Of Its Release

- Xbox Game Pass September Wave 1 Revealed

- INR RUB PREDICTION

- Best Ship Quest Order in Dragon Quest 2 Remake

2026-02-13 18:54