Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have developed a completely solvable Path Integral Monte Carlo model for interacting harmonic fermions, providing unprecedented insights into the notoriously difficult fermion sign problem.

This work presents an exact PIMC model demonstrating a new class of Variable-Bead algorithms with improved accuracy for simulating quantum dots and other fermionic systems.

The notorious fermion sign problem continues to limit accurate simulations of many-body quantum systems, yet analytical progress remains scarce. This work, ‘Understanding the sign problem from an exact Path Integral Monte Carlo model of interacting harmonic fermions’, introduces a completely solvable Path Integral Monte Carlo (PIMC) model for interacting harmonic fermions, providing unprecedented insight into the origins and behavior of the sign problem in any dimension. Specifically, the study demonstrates that pairwise interactions shift, but do not exacerbate, the severity of the sign problem, and even eliminate it for closed-shell fermion numbers at large imaginary time-results validated through comparisons with neural network predictions for quantum dots containing up to 110 electrons. Could this exactly solvable model serve as a benchmark for developing improved algorithms to tackle the sign problem in more complex fermionic systems?

The Fermion Sign Problem: A Fundamental Obstacle

Accurate modeling of materials and chemical reactions often hinges on understanding the behavior of fermions – particles that obey the Pauli exclusion principle, such as electrons. Techniques like Path Integral Monte Carlo (PIMC) offer a powerful approach to simulating these many-fermion systems, allowing researchers to predict material properties and explore complex chemical processes. By representing quantum particles as ‘paths’ in time, PIMC can, in principle, calculate crucial thermodynamic quantities like energy and pressure. This capability is vital for designing novel materials with specific characteristics, understanding high-temperature superconductivity, and even simulating the behavior of matter under extreme conditions, such as those found in the cores of planets or stars. The success of these simulations, however, is intrinsically linked to overcoming significant computational challenges, particularly when dealing with a large number of interacting fermions.

The notorious ‘Fermion Sign Problem’ fundamentally challenges simulations of systems containing fermions – particles like electrons that obey the Pauli Exclusion Principle. This principle dictates that no two identical fermions can occupy the same quantum state, leading to antisymmetric wavefunctions that can be either positive or negative. When employing methods like Path Integral Monte Carlo, these fluctuating signs cause destructive interference; positive and negative contributions to the calculation increasingly cancel each other out. As the number of fermions grows, the signal-to-noise ratio plummets exponentially, demanding computational resources that quickly become intractable. Consequently, accurately determining even basic properties – such as the ground state energy – of many-fermion systems remains a significant obstacle in fields ranging from materials science to quantum chemistry, effectively limiting the complexity of models that can be realistically investigated.

Calculating the thermodynamic energy of systems composed of fermions-particles like electrons that obey the Pauli Exclusion Principle-poses a significant challenge for conventional computational methods. The core difficulty stems from the antisymmetric nature of the fermionic wavefunction, which introduces fluctuating signs in the mathematical integrals used to determine energy and other crucial properties. As the number of fermions increases, these fluctuations intensify, leading to exponentially growing computational cost and ultimately rendering accurate calculations intractable for all but the simplest systems. This limitation hinders progress in diverse fields, from materials science-where understanding electron behavior is vital for designing new materials-to quantum chemistry, where precise energy calculations are fundamental for predicting molecular properties and reaction rates. Consequently, researchers are actively pursuing novel algorithms and techniques to circumvent the fermion sign problem and unlock the potential for simulating complex fermionic systems with greater accuracy and efficiency.

Harmonic Fermions: A Foundation for Analytical Tractability

The simplification of the many-body problem in fermionic systems is achieved through the use of harmonic potentials to model pairwise interactions. Unlike more complex, realistic potentials, the harmonic potential V(r) = \frac{1}{2}kr^2 allows for analytical solutions and facilitates calculations while preserving essential fermionic behavior, namely the antisymmetric wave function requirement dictated by the Pauli exclusion principle. This approach avoids the complexities introduced by short-range correlations and many-body effects inherent in more accurate, but computationally expensive, interaction models. By focusing on harmonic interactions, the resulting system retains the fundamental quantum statistics of fermions without necessitating the full treatment of complex potential energy surfaces.

The derivation of a Discrete Path Integral Monte Carlo (PIMC) Propagator is central to the analytical tractability of the harmonic fermion model. This propagator, expressed as K(q, \tau) = \langle q | e^{-\tau H} | q \rangle, facilitates the efficient evaluation of the many-body propagator for fermions interacting via harmonic potentials. Unlike conventional PIMC which often requires extensive sampling and suffers from the sign problem, the discrete nature of the harmonic potential allows for a simplified, analytical form of the propagator. This simplification enables direct calculation of Hamiltonian and thermodynamic energies without the need for computationally expensive Monte Carlo integration, providing a significant advantage for studying many-fermion systems.

The Discrete Path Integral Monte Carlo (PIMC) method, while powerful, faces computational challenges stemming from the fermion sign problem and the need for extensive sampling to accurately represent the many-body wave function. Utilizing the derived Discrete PIMC Propagator for harmonic fermions allows for a reduction in these bottlenecks by enabling efficient propagation of the system’s wave function in imaginary time. This propagator facilitates calculations of both Hamiltonian energies – representing the system’s total energy – and thermodynamic energies, such as free energy and entropy, with significantly improved computational efficiency compared to traditional PIMC implementations. The propagator achieves this by streamlining the evaluation of the path integral, reducing the number of required sampling steps and mitigating the impact of the fermion sign problem in this specific, tractable model.

Refining the Approach: Variable Beads and Discrete Partition Functions

Variable-Bead Algorithms, when integrated into the Path Integral Monte Carlo (PIMC) method, enhance computational efficiency by introducing multiple ‘beads’ representing a single particle’s trajectory over an imaginary time interval. This discretization allows for a more flexible sampling of the path integral, reducing autocorrelation between configurations and accelerating convergence rates. By increasing the number of beads, the time step can be effectively reduced without a corresponding increase in computational cost, enabling accurate simulations of systems with improved statistical precision. The method’s optimization stems from better representation of the particle’s dynamics and more efficient exploration of the configuration space, particularly benefiting calculations involving many-body systems.

Discretization of the path integral within the PIMC method transforms the continuous integral into a summation over discrete configurations. This is mathematically formalized as the ‘Discrete Fermion Partition Function,’ which represents the partition function in a discretized space. Crucially, this formulation allows the partition function to be expressed as a determinant, Z = det(A), where A is a matrix constructed from the discretized propagator and system parameters. Determinant evaluation is computationally efficient – scaling as O(N^3) for an N x N matrix – and facilitates the calculation of thermodynamic properties by avoiding direct summation over exponentially many configurations. This determinant-based approach is particularly beneficial for fermionic systems, offering a significant performance improvement compared to traditional Monte Carlo methods.

The utilization of a discrete partition function in conjunction with a propagator offers a means of mitigating the sign problem inherent in Path Integral Monte Carlo (PIMC) simulations of fermionic systems. This approach facilitates accurate energy calculations for harmonic fermions by effectively managing the contributions of different path configurations. Current results demonstrate that energies calculated using this method are within 0.5% of those obtained with modern neural network techniques, with demonstrated accuracy up to systems containing 90 electrons. This level of precision is achieved through efficient evaluation of the determinant within the discrete partition function, allowing for reliable simulation of larger fermionic systems than previously possible.

Validating the Approach: Spin-Balanced Quantum Dots as a Benchmark

Spin-balanced quantum dots represent a valuable benchmark for Path Integral Monte Carlo (PIMC) methods due to their inherent symmetry and controlled many-body interactions. These systems are defined by an equal population of spin-up and spin-down electrons, effectively canceling out net magnetization and simplifying the computational complexity. This balanced configuration allows for rigorous testing of PIMC algorithms designed to handle fermionic systems, providing a realistic scenario without the complications introduced by spin polarization. The use of spin-balanced quantum dots facilitates validation of the PIMC method’s ability to accurately simulate the behavior of interacting fermions in confined geometries, serving as a crucial step towards tackling more complex quantum systems.

The methodology established for simulating harmonic fermions was successfully adapted to model electrons within spin-balanced quantum dots. This involved leveraging the techniques previously developed for handling fermionic statistics and interparticle interactions in the harmonic potential, extending their application to the more complex, yet still tractable, system of quantum dots. The core principles of the Path Integral Monte Carlo (PIMC) method, including the use of permutation symmetry and the development of efficient trial wavefunctions, remained consistent, allowing for accurate simulations of electron behavior and providing a benchmark for validating the approach against established methods like the SJ method.

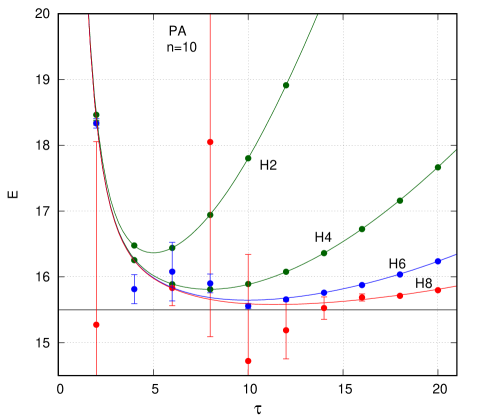

The Variable-Bead 3 (VB3) algorithm demonstrates high accuracy in simulating quantum dots, achieving mean energy deviations of 0.3% when compared against the Serpent-Jordan (SJ) method across systems containing 30, 42, 56, and 72 electrons, at simulation parameters of τ=6, 4, 4, and 3, respectively. The Variable-Bead 2 (VB2) algorithm exhibits slightly increased deviation, reaching 0.5% for the n=72 system and between 0.7% and 0.8% for the n=6 system, indicating a performance improvement with the VB3 implementation. These results confirm the precision of the method in modeling electron behavior within spin-balanced quantum dots.

Beyond Harmonics: Paving the Way for Realistic Material Simulations

The success of discrete propagators and variable-bead algorithms in simulating the harmonic potential isn’t merely a demonstration within a simplified system; it establishes a versatile toolkit applicable to significantly more complex scenarios. These techniques aren’t limited by the parabolic shape of the harmonic well and can be readily adapted to model the 1/r behavior inherent in the Coulomb potential – a crucial step towards simulating realistic materials. This adaptability allows researchers to move beyond idealized models and begin investigating the behavior of strongly correlated electron systems, paving the way for a deeper understanding of phenomena like high-temperature superconductivity and the exotic quantum states found in novel materials. The core innovation lies in the methods’ ability to efficiently handle the interactions between particles, regardless of the specific form of the potential governing those interactions.

The ability to accurately model strongly correlated electron systems represents a significant leap forward in materials science. These materials, where electron interactions dominate, often exhibit exotic behaviors like high-temperature superconductivity – the transmission of electricity with zero resistance at relatively accessible temperatures. Current computational methods struggle with these systems due to the complexity of accounting for electron-electron interactions. However, by extending techniques initially developed for harmonic potentials, researchers can now simulate the behavior of electrons within realistic materials, offering a pathway to understanding the fundamental mechanisms driving these quantum phenomena. This enhanced capability promises to accelerate the discovery of new materials with tailored electronic properties and potentially revolutionize fields ranging from energy transmission to quantum computing.

Continued development centers on scaling these computational techniques to encompass larger, more complex systems – a crucial step towards modeling real-world materials. Researchers are actively investigating novel algorithmic approaches designed to mitigate the inherent computational expense of simulating strongly correlated electrons. This includes exploring innovative variable-bead implementations and refining discrete propagator methods to achieve both increased accuracy and reduced processing time. The ultimate goal is to enable the investigation of emergent quantum phenomena in materials exhibiting complex interactions, paving the way for advancements in fields like high-temperature superconductivity and quantum computing.

The pursuit of elegant solutions in computational physics mirrors a deeper quest for understanding the fundamental nature of reality. This study, by offering a completely solvable Path Integral Monte Carlo model, provides a pristine landscape for examining the notorious fermion sign problem. It’s a testament to the power of refined methodology – akin to distilling a complex system down to its essential components. As Niels Bohr once stated, “Every great advance in natural knowledge begins with an intuition that is not immediately justifiable.” This intuition, coupled with the meticulous application of Variable-Bead algorithms, allows researchers to probe the behavior of interacting harmonic fermions with unprecedented accuracy, pushing the boundaries of quantum dot simulations and revealing the underlying harmony of these complex systems. The clarity achieved in this model isn’t merely a computational feat; it is a demonstration of how a deep understanding of the problem can lead to solutions that are both beautiful and profoundly insightful.

Beyond the Horizon

The presented work, while offering a completely solvable model-a rare and satisfying achievement-does not, of course, solve the fermion sign problem. Rather, it illuminates its subtle architecture. The elegance of the harmonic system allows a detailed examination of the mechanisms at play, but the true test lies in extending these insights to more complex, less forgiving potentials. The demonstrated Variable-Bead algorithms represent a refinement, not a revolution; increased accuracy comes at a cost, and the search for genuinely scalable methods continues. Each screen and interaction must be considered.

A critical limitation remains the inherent simplicity of the harmonic potential. Real quantum dots, and indeed most physical systems, exhibit interactions that are decidedly anharmonic. The introduction of even modest deviations from harmonicity will undoubtedly introduce complexities that challenge the current approach. A fruitful avenue for future research involves systematically exploring the impact of these deviations, quantifying the degradation of the signal, and developing strategies to mitigate it. Aesthetics humanize the system.

Ultimately, the quest to understand-and perhaps one day tame-the fermion sign problem is not merely a technical exercise. It is a fundamental challenge to our ability to model and predict the behavior of quantum matter. The path forward demands not only algorithmic innovation but also a deeper appreciation for the underlying physics and a willingness to embrace the inherent limitations of computational methods.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.22559.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Poppy Playtime Chapter 5: Engineering Workshop Locker Keypad Code Guide

- Jujutsu Kaisen Modulo Chapter 23 Preview: Yuji And Maru End Cursed Spirits

- God Of War: Sons Of Sparta – Interactive Map

- Poppy Playtime 5: Battery Locations & Locker Code for Huggy Escape Room

- Who Is the Information Broker in The Sims 4?

- 8 One Piece Characters Who Deserved Better Endings

- Pressure Hand Locker Code in Poppy Playtime: Chapter 5

- Poppy Playtime Chapter 5: Emoji Keypad Code in Conditioning

- Why Aave is Making Waves with $1B in Tokenized Assets – You Won’t Believe This!

- All Kamurocho Locker Keys in Yakuza Kiwami 3

2026-02-02 23:58