Author: Denis Avetisyan

Research reveals a connection between the internal structure of quarks and the observed degeneracy of meson masses, challenging conventional understandings of chiral symmetry restoration.

This study investigates the link between the analytic structure of the quark propagator and meson mass degeneracies within a Dyson-Schwinger/Bethe-Salpeter framework.

The emergence of mass in hadrons remains a central challenge in quantum chromodynamics, often framed through the lens of chiral symmetry breaking. This is explored in ‘Chiral symmetry restoration effects onto the meson spectrum from a Dyson-Schwinger/Bethe-Salpeter approach’, which investigates the connection between the analytic structure of the quark propagator and meson mass degeneracies. Specifically, the study demonstrates that these degeneracies arise not simply from symmetry restoration, but are fundamentally linked to the location of quark propagator poles relative to the integration domain in the Bethe-Salpeter equation. Could a deeper understanding of this connection illuminate the dynamical emergence of symmetries in QCD, particularly at temperatures near the crossover transition?

The Quark’s Prophecy: Mapping the Strong Force

The properties of hadrons – composite particles like protons and neutrons – are fundamentally dictated by the behavior of the quarks they contain, and understanding this relationship requires a precise mapping of the quark propagator. This propagator, a central object in Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD), essentially describes how a quark travels through spacetime within the hadron, accounting for interactions with the strong force and other quarks. Because hadrons are not simply the sum of their parts, but emerge from the complex dynamics of these confined quarks, an accurate depiction of the quark propagator is paramount. It’s not merely a theoretical construct; it underpins calculations of crucial hadronic properties like mass, spin, and magnetic moment, and serves as the essential building block for exploring the internal structure of matter at the most fundamental level. Without a robust understanding of the quark propagator, precise theoretical predictions about hadron behavior remain elusive.

The strong force, governing interactions between quarks and gluons, presents a unique challenge to physicists attempting to precisely calculate hadron properties. Unlike electromagnetism, where interactions become weaker at shorter distances, the strong force strengthens with increasing energy, a phenomenon known as asymptotic freedom in reverse. This ‘strong coupling’ renders traditional perturbative methods – the workhorse of many quantum field theory calculations – largely ineffective. These methods rely on approximating solutions through a series of increasingly small corrections, but the strong coupling prevents convergence, leading to inaccurate or meaningless results. Consequently, alternative non-perturbative techniques are essential to navigate the complex dynamics within hadrons and accurately model their behavior, demanding innovative theoretical frameworks and substantial computational resources to overcome these inherent limitations.

Mapping the intricate dynamics of quarks confined within hadrons demands a departure from standard perturbative techniques, which falter under the influence of the strong force. A non-perturbative approach becomes essential, employing methods like lattice Quantum Chromodynamics and various model-based calculations to probe the complex interactions beyond simple approximations. These investigations reveal that quarks aren’t simply free particles, but are instead embedded within a dynamic, fluctuating environment of gluons and quark-antiquark pairs – a ‘sea’ which significantly alters their behavior. Successfully charting this internal landscape is not merely an academic exercise; it provides the foundational data necessary for developing more advanced theoretical tools, ultimately enabling researchers to accurately predict hadron properties and understand the strong force’s role in the universe.

The Dyson-Schwinger Equation: A Framework for Emergence

The Dyson-Schwinger equation (DSE) is a functional equation used in quantum field theory to calculate Green’s functions, notably the quark propagator S(p). Unlike perturbative methods which rely on expansions in coupling constants and thus struggle with strong coupling regimes, the DSE provides a non-perturbative approach. This is achieved by expressing the quark propagator in terms of its self-energy \Sigma(p) and incorporating all possible one-particle-irreducible (1PI) diagrams, effectively summing an infinite series of diagrams. Traditional perturbative calculations become unreliable when dealing with phenomena like dynamical chiral symmetry breaking and confinement, while the DSE offers a framework to investigate these non-perturbative aspects of Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD) directly, although practical calculations often require truncation schemes like the Rainbow-Ladder approximation.

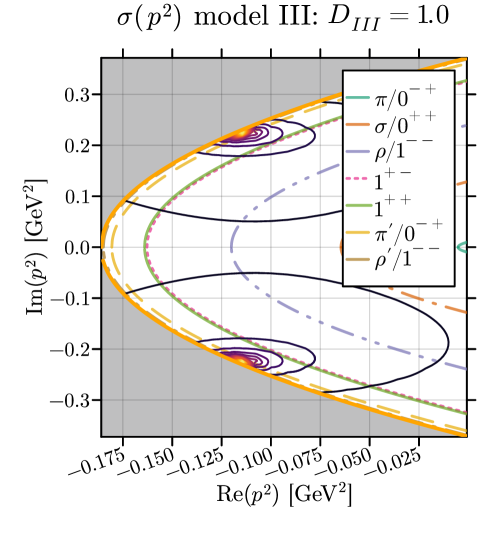

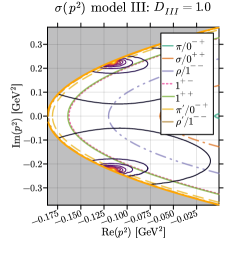

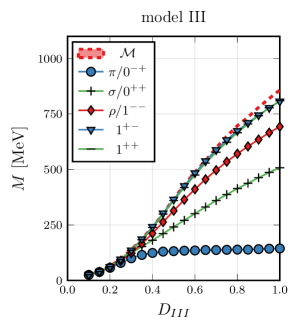

The Dyson-Schwinger equation’s versatility allows for the systematic investigation of quark confinement through the implementation of varying interaction models. Model I represents a simple instantaneous interaction, while Model II introduces a more complex, momentum-dependent interaction mediated by gluon exchange. Model III extends this further by incorporating a scalar-gluon vertex, potentially altering the infrared behavior of the quark propagator \Gamma(p) . Each model alters the effective interaction between quarks and gluons, resulting in different solutions to the Dyson-Schwinger equation and consequently, different predictions for confinement mechanisms and the mass function of quarks. By comparing the solutions obtained with these diverse models, researchers can evaluate the impact of different interaction structures on the fundamental properties of strongly interacting matter.

The Rainbow-Ladder approximation is a key truncation of the Dyson-Schwinger equation utilized to solve for the quark propagator. It achieves computational feasibility by considering only the ladder-type contributions to the self-energy integral, effectively summing all one-particle-irreducible (1PI) diagrams with an infinite number of gluon exchanges. This approximation neglects contributions from crossed and transverse gluon diagrams, thereby simplifying the integral equation while preserving the essential dynamical mechanism responsible for dynamical chiral symmetry breaking and confinement. Specifically, the quark propagator S(p) = \frac{1}{i\slashed{p} - m_0 - \Sigma(p^2)} is determined through a self-consistent solution, where \Sigma(p^2) represents the quark self-energy, and the Rainbow-Ladder truncation defines the specific form of the kernel in the Dyson-Schwinger equation.

Decoding the Internal Structure: Poles and Hadron Properties

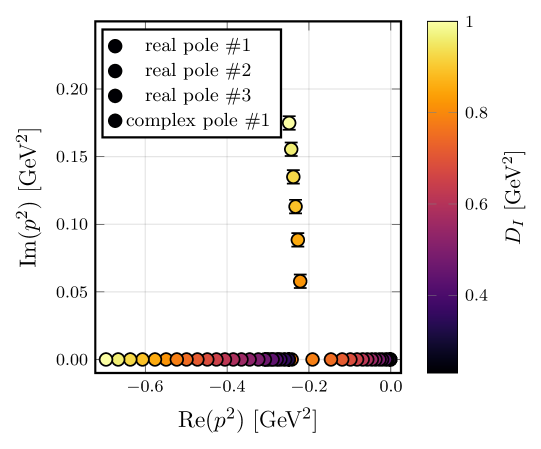

The pole structure of the quark propagator, defined by the location of poles in the complex momentum plane, directly reflects its analytic properties. Poles correspond to singularities in the propagator, and their positions – both real and imaginary components – determine the propagator’s behavior and, consequently, the properties of the hadrons it describes. Specifically, the residue at each pole is related to the strength of the corresponding state, while the pole’s location dictates its mass and lifetime. A simple pole indicates a stable particle, while complex poles signify resonant states with finite widths; the imaginary part of the pole position is inversely proportional to the particle’s lifetime. Analyzing the density and distribution of these poles allows for the determination of bound states, scattering resonances, and the overall analytic continuation of the quark propagator.

Complex conjugate poles in the quark propagator signify the existence of resonant states, which are short-lived composite particles. These poles manifest as peaks in scattering amplitudes and directly relate to observable hadron properties. The real part of the pole position corresponds to the mass of the resonant state, while the imaginary part is proportional to its width, or inverse lifetime. A larger imaginary component indicates a broader, more unstable resonance, reflecting a faster decay rate. Analysis of these pole positions, therefore, provides quantitative data for determining hadron masses and widths, connecting theoretical calculations to experimentally measurable quantities.

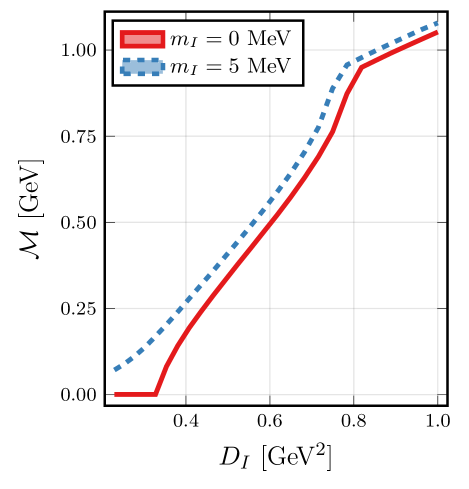

The quark propagator, which describes the propagation of quarks, undergoes a significant change in its analytic structure at an interaction strength of 0.23 GeV². Below this value, the propagator is characterized by a single pole in the complex momentum plane. However, at precisely 0.23 GeV², this single pole bifurcates, resulting in a degenerate pair of poles. This transition indicates a critical point where the analytic properties of the propagator fundamentally change, moving from a simple single-pole representation to a more complex, two-pole structure. The degeneracy of the poles implies that the two resulting states are closely related in energy and momentum, and this bifurcation has direct implications for understanding the formation and properties of hadrons.

The pole structure of the quark propagator, as determined through analytic continuation to complex momentum space, directly correlates with experimentally measurable hadron properties. Specifically, the location of poles – their real and imaginary components – provide information about hadron masses and widths, respectively. \Gamma = 2Im(p) , where Γ is the width and p represents the pole position. Deviations in pole locations, induced by changes in interaction strength, manifest as shifts in observed resonance energies and decay rates. Therefore, detailed analysis of the pole structure serves as a critical bridge between the abstract theoretical framework of the quark propagator and concrete, observable physical quantities associated with hadron spectroscopy.

The Symphony of Symmetry: Unveiling the Strong Force’s Design

The spectrum of mesons, composite particles made of quarks and antiquarks, presents a curious phenomenon: numerous mesons exhibit remarkably similar masses, a condition known as degeneracy. This isn’t a random occurrence; rather, it strongly suggests the presence of underlying symmetries governing the strong interaction, one of the four fundamental forces of nature. These symmetries, if present, would dictate that certain combinations of quark and antiquark states have the same energy, manifesting as these observed degenerate masses. Investigating these patterns provides crucial insight into the dynamics of the strong force, which, unlike electromagnetism, does not diminish with distance, and is responsible for binding quarks together within hadrons like mesons and baryons. The degree to which this degeneracy holds, and how it is broken, offers a window into the very structure of matter at its most fundamental level, and motivates exploration of theoretical frameworks – such as chiral spin symmetry – designed to explain these intriguing observations.

Chiral Spin Symmetry offers a compelling explanation for the observed degeneracy in meson masses, positing that the strong force exhibits a particular sensitivity to the combined effect of chiral and spin quantum numbers. This symmetry predicts a specific arrangement within the hadron spectrum, where mesons possessing similar chiral and spin characteristics should display nearly identical masses. The framework stems from considering the light quark masses as perturbations to a symmetry existing in the limit of massless quarks, leading to predictable splittings and groupings of mesons. Consequently, analyzing the observed meson spectrum through the lens of Chiral Spin Symmetry allows physicists to identify expected patterns and, crucially, to probe the underlying dynamics of the strong interaction by investigating deviations from these predicted arrangements. This approach facilitates a deeper understanding of how quarks bind together to form these composite particles and reveals subtle details about the nature of the strong force itself.

Understanding the spectrum of mesons – composite particles crucial to the strong force – demands a robust theoretical framework, and the Bethe-Salpeter equation provides just that. This equation, a cornerstone of relativistic bound-state theory, allows physicists to calculate the properties of mesons by directly incorporating the interactions between their constituent quarks. Critically, the equation requires a precise understanding of the quark propagator, which describes the behavior of quarks within the strong interaction. By leveraging sophisticated computational techniques to calculate this propagator, researchers can then solve the Bethe-Salpeter equation and predict the masses and other characteristics of various mesons. These predictions serve as vital tests for proposed symmetries, such as chiral spin symmetry, confirming or refining the theoretical models used to describe the fundamental building blocks of matter and the forces that bind them. The accuracy of this approach hinges on a detailed understanding of the underlying quark dynamics, making the Bethe-Salpeter equation an indispensable tool in hadron physics.

Investigations into the strong force reveal that chiral symmetry, while present in the theory, is not a strict symmetry of nature; rather, it undergoes spontaneous breaking. This dynamical chiral symmetry breaking manifests at a characteristic interaction strength of 0.332 GeV², a value determined by observing the splitting of degenerate poles in calculations of the quark propagator. These poles, representing bound states of quarks, move away from coinciding at this interaction strength, signifying the breaking of symmetry. Notably, the degree of this pole splitting directly correlates with the observed degeneracies in the masses of mesons – composite particles made of quarks and antiquarks. This correlation suggests a fundamental connection between the internal dynamics of quark interactions and the observed spectrum of hadrons, implying that meson mass degeneracy isn’t solely a consequence of abstract symmetry arguments, but a physical effect stemming from the strong force’s self-induced symmetry breaking.

Recent investigations into the strong force reveal a compelling link between the location of poles in calculated quark propagators and the observed degeneracy of meson masses, hinting at a deeper mechanism than previously understood through conventional symmetry arguments. While chiral spin symmetry provides a valuable framework for predicting these degeneracies, the direct correspondence with pole locations suggests a dynamical origin – the interaction strength itself appears to dictate the pattern of meson masses. Specifically, an interaction scale of approximately 0.332 GeV² correlates with the splitting of previously degenerate poles, mirroring the observed mass differences in the meson spectrum. This finding proposes that the strong interaction’s inherent dynamics – the way quarks bind together – is fundamentally responsible for the observed meson structure, potentially operating alongside, or even independent of, the symmetries traditionally invoked to explain it. This suggests that understanding the interaction strength and its impact on quark propagation may offer a more complete picture of hadron formation than relying solely on symmetry principles.

The pursuit of understanding hadronic physics, as demonstrated by this investigation into chiral symmetry restoration, reveals a curious tendency. One attempts to impose order through theoretical frameworks – the Dyson-Schwinger and Bethe-Salpeter equations – yet the results suggest the underlying reality is more nuanced. The observed meson mass degeneracies aren’t simply a consequence of symmetry, but appear intrinsically linked to the analytic structure of the quark propagator itself. As Simone de Beauvoir observed, “One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.” Similarly, these mesons aren’t defined by symmetry, but become degenerate through the complex interplay of forces and propagators. The perfect architecture, a complete and symmetrical understanding, remains elusive; this work, like so much in theoretical physics, merely charts another step along a path destined to reveal ever-greater complexity.

What Lies Ahead?

The pursuit of hadronic spectra, framed by the analytic structure of the quark propagator, reveals less a pathway to definitive symmetry restoration and more a cartography of inherent limitations. This work, by focusing attention on the poles of the propagator as the source of meson mass degeneracies, does not solve the problem of chiral symmetry breaking; it relocates the interesting failures. It suggests that any architectural choice made in modeling these systems – any attempt to force a predictable outcome – is, in fact, a prophecy of future revelation.

Future investigations will inevitably confront the question of whether these poles represent genuine dynamical states, or merely artifacts of the truncation schemes employed. Monitoring the sensitivity of these results to variations in the modeling of Green’s functions is not simply a matter of error analysis; it is the art of fearing consciously. True resilience, in this context, begins where certainty ends, demanding an embrace of ambiguity rather than a striving for absolute prediction.

The field now faces a choice: continue refining the theoretical machinery, attempting to achieve ever-greater quantitative agreement with experiment, or shift focus toward understanding the kinds of failures that are systematically revealed by these approaches. The latter path acknowledges that these systems are not tools to be built, but ecosystems to be observed, and that the most profound insights arise not from successes, but from the graceful acceptance of inevitable collapse.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.17456.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Poppy Playtime Chapter 5: Engineering Workshop Locker Keypad Code Guide

- Jujutsu Kaisen Modulo Chapter 23 Preview: Yuji And Maru End Cursed Spirits

- God Of War: Sons Of Sparta – Interactive Map

- 8 One Piece Characters Who Deserved Better Endings

- Who Is the Information Broker in The Sims 4?

- Poppy Playtime 5: Battery Locations & Locker Code for Huggy Escape Room

- Pressure Hand Locker Code in Poppy Playtime: Chapter 5

- Mewgenics Tink Guide (All Upgrades and Rewards)

- Poppy Playtime Chapter 5: Emoji Keypad Code in Conditioning

- Engineering Power Puzzle Solution in Poppy Playtime: Chapter 5

2026-02-22 01:30