Author: Denis Avetisyan

This review explores the growing threat of power side-channel attacks and the techniques used to exploit vulnerabilities in electronic devices.

A comprehensive survey of application-specific power side-channel attacks, analysis methods, and evolving countermeasures for cryptographic implementations.

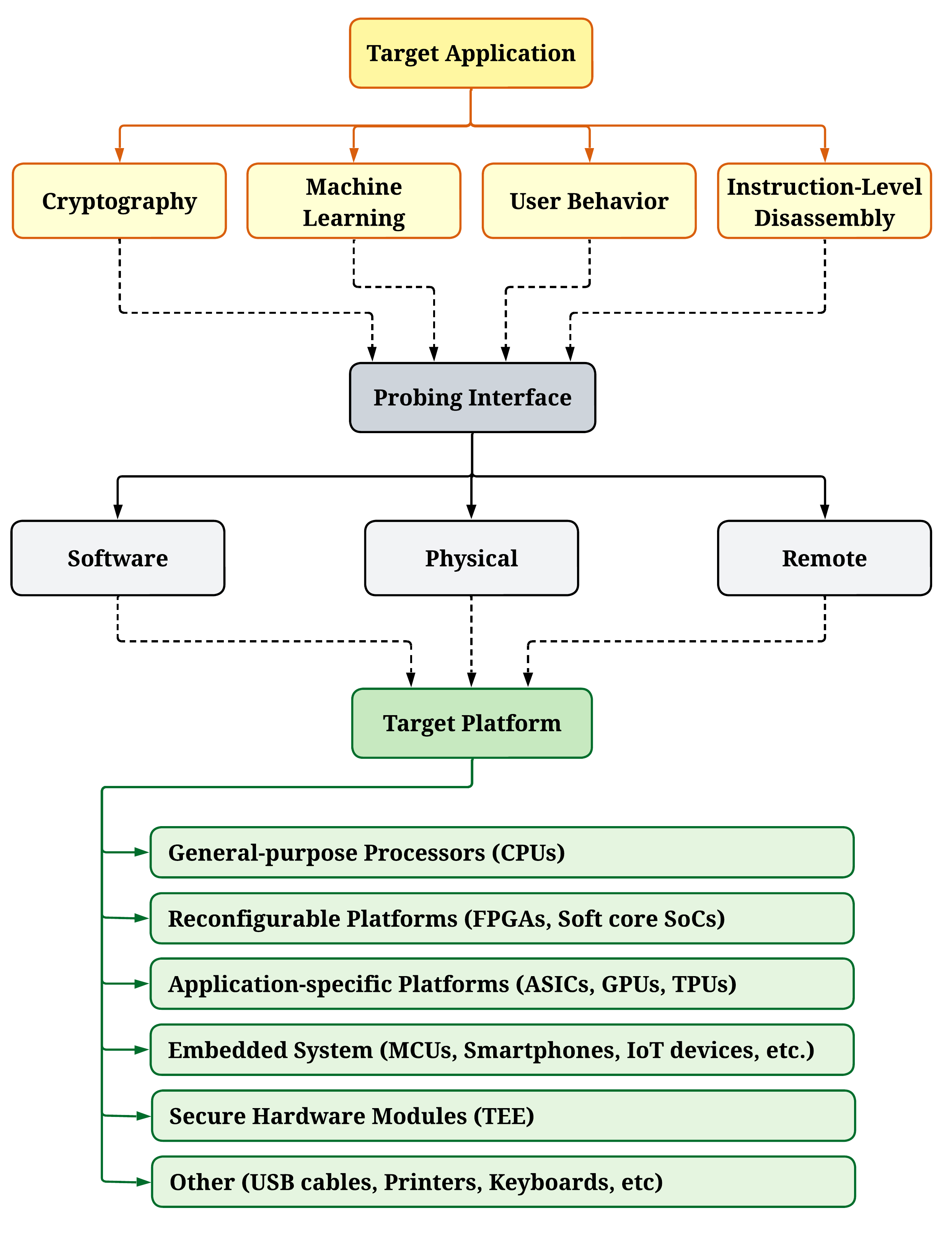

Despite increasing sophistication in hardware security, electronic devices remain vulnerable to side-channel attacks that exploit unintended physical emanations. This paper, ‘Application-Specific Power Side-Channel Attacks and Countermeasures: A Survey’, comprehensively examines power side-channel analysis, moving beyond traditional cryptographic implementations to explore emerging threats in areas like machine learning and user behavior analysis. Our survey classifies recent attack methodologies and corresponding countermeasures, providing a comparative assessment tailored to specific application domains. As these attacks evolve alongside technological advancements, what novel defenses will be required to secure increasingly complex systems against power-based leakage?

The Illusion of Security: Beyond Mathematical Proofs

Though modern cryptographic algorithms rely on complex mathematical principles to safeguard data, their security isn’t solely determined by computational difficulty. A system’s actual implementation-the physical hardware and software executing these algorithms-introduces vulnerabilities. These flaws aren’t errors in the mathematics itself, but rather unintended information leakage arising from the physical processes of computation. Factors like power consumption, electromagnetic radiation, timing variations, and even sound can reveal clues about the secret key being used. Consequently, even an algorithm proven unbreakable in theory can be compromised through analysis of its physical manifestation, highlighting a critical distinction between cryptographic theory and real-world application. This necessitates a shift in focus towards hardware-aware security measures and a holistic approach to cryptographic system design.

Side-channel attacks represent a fundamental shift in cryptographic vulnerability, moving beyond mathematical weaknesses to exploit the physical implementation of security systems. Rather than breaking the encryption algorithm itself, these attacks cleverly analyze unintended information leakage during computation-such as the minute variations in power consumption, electromagnetic radiation, or even processing time-to deduce the secret key. A seemingly innocuous correlation between a device’s operational characteristics and the data it processes can reveal critical information to an attacker. For example, a cryptographic operation requiring more power when processing a ‘1’ bit versus a ‘0’ creates a measurable side-channel. This leakage, though subtle, provides enough information for sophisticated analysis techniques – like statistical analysis or machine learning – to gradually reconstruct the key, effectively bypassing the mathematical security of the encryption.

The proliferation of embedded systems, the expanding Internet of Things, and the reliance on cloud infrastructure have created a vast and increasingly vulnerable attack surface for side-channel exploits. Unlike traditional cyberattacks that target algorithmic weaknesses, these attacks target the physical implementation of security, meaning devices with seemingly secure cryptography can be compromised by analyzing characteristics like power consumption, electromagnetic radiation, or even processing time. This presents a unique challenge, as standard software defenses are often ineffective; a smart lock, industrial sensor, or cloud server could reveal its cryptographic keys without any direct code breach. The sheer scale of these interconnected devices, often deployed in physically insecure locations and with limited resources for robust security measures, amplifies the risk, potentially enabling widespread data breaches or system manipulation.

A significant body of research demonstrates the continued importance of power side-channel attacks within the broader field of cryptographic implementation security. Analysis of publications between 2015 and 2020 reveals that these attacks, which leverage variations in electrical power consumption during computation to reveal secret keys, accounted for 36.5% of all published work. This statistic underscores the practical threat posed by power analysis, even as cryptographic algorithms themselves remain mathematically sound. The prevalence suggests that attackers frequently target the implementation of cryptography, rather than attempting to break the algorithms directly, and highlights the need for ongoing development of countermeasures specifically designed to mitigate power-based leakage.

The evolving landscape of side-channel attacks necessitates increasingly detailed investigation into the fundamental processes that enable them. Early attacks often relied on simple power analysis, but contemporary methodologies employ techniques like electromagnetic analysis, fault injection, and even acoustic monitoring to extract sensitive information. This progression demands not merely the development of countermeasures, but a granular understanding of how cryptographic operations manifest physically within hardware. Researchers are now delving into the nuances of transistor-level behavior, signal propagation characteristics, and the subtle interplay between software and silicon to identify previously unknown leakage pathways. This deeper comprehension is crucial for designing truly secure systems capable of resisting not only current attacks, but also the more sophisticated methodologies that are actively being developed.

Profiling vs. Blind Guessing: Knowing Your Target

Side-channel attacks are broadly categorized as either profiled or non-profiled, based on whether the attacker requires pre-characterization of the target device. Profiled attacks necessitate an initial profiling phase where power consumption, electromagnetic radiation, or other measurable characteristics are observed during the execution of known operations. This collected data forms a model, or profile, of the device’s behavior. Conversely, non-profiled attacks do not require this initial characterization; they attempt to extract secret keys or other sensitive information directly from real-time measurements without a pre-established device model. The distinction impacts the complexity of the attack and the resources required, with profiled attacks typically demanding more upfront effort but potentially achieving higher success rates.

Profiled attacks, most notably Template Attacks, necessitate a pre-characterization phase where the target device’s power consumption is measured during the execution of known operations. This involves acquiring a dataset of power traces, correlated with the processed data or intermediate values, to build a statistical model representing the device’s energy profile. The model, or “template,” captures the relationship between the processed data and the observed power consumption. This pre-processing step allows the attacker to distinguish between different operations performed by the device based on its power signature, even without direct knowledge of the key or internal state during the attack phase. The accuracy of the attack is directly correlated to the size and quality of the profiling dataset and the sophistication of the statistical modeling techniques employed.

Non-profiled side-channel attacks, including Simple Power Analysis (SPA) and Correlation Power Analysis (CPA), do not require a pre-characterization phase of the target device’s power consumption. SPA directly observes power traces to infer key information from distinct patterns correlated with operations. CPA, conversely, utilizes statistical methods to identify weak correlations between power consumption and hypothesized key values without needing a pre-built power model. This characteristic allows non-profiled attacks to be executed with reduced effort and preparation compared to profiled attacks, though they generally require a larger number of power traces to achieve successful key recovery.

Traditional template attacks require a substantial number of power consumption traces during the profiling phase to accurately model the target device’s characteristics. Recent developments in stochastic modeling techniques for template attacks have significantly reduced this requirement without substantial performance degradation. These advancements utilize probabilistic methods to represent the profiled data, allowing for accurate key recovery with fewer traces – often an order of magnitude fewer – than conventional template attacks. This reduction in trace requirements lowers the barrier to entry for attackers, as acquiring a large dataset of profiled power traces can be difficult and time-consuming, but the resulting performance remains comparable to that achieved with more extensive profiling datasets.

The selection between profiled and non-profiled side-channel attacks is fundamentally dictated by the attacker’s access to the target device and the intricacies of the cryptographic implementation. Non-profiled attacks, while simpler to execute, generally require a larger number of power traces to reliably extract the key, and their success is heavily influenced by the noise levels and the signal strength of the target device. Profiled attacks, demanding initial device characterization, become more effective against complex implementations or when only a limited number of traces can be acquired during the attack phase. Furthermore, if the attacker has limited physical access preventing extensive measurement campaigns for profiling, a non-profiled approach may be the only viable option, despite its potentially lower success rate.

Digging Into the Leakage: How the Attacks Work

Differential Power Analysis (DPA) is a statistical side-channel attack that exploits the correlation between a device’s power consumption and the data it is processing. This technique relies on the fact that digital circuits consume slightly different amounts of power depending on the specific bits being manipulated; these variations, while individually small, can be statistically analyzed to reveal secret keys or other sensitive information. DPA attacks involve collecting numerous power traces – measurements of power consumption over time – while the device performs cryptographic operations. These traces are then statistically analyzed, often using correlation or difference-of-means methods, to determine the probability of different key candidates being correct. The effectiveness of DPA is predicated on a sufficient number of power traces and an accurate power model representing the relationship between data and power consumption.

Differential Power Analysis (DPA) relies on power models to establish a statistical relationship between a device’s power consumption and the data it processes. Two common models are Hamming Weight, which correlates power consumption to the number of ‘1’ bits in a data value, and Hamming Distance, which correlates power consumption to the number of bits that differ between two data values. These models are used to generate hypotheses about intermediate values within a cryptographic operation. By analyzing numerous power traces – recordings of the device’s power consumption over time – and statistically correlating them with these hypothesized values, attackers can deduce secret keys. The success of DPA depends on the correlation between the power model and the actual power consumption, and the ability to distinguish signal from noise within the collected power traces.

Differential Power Analysis (DPA) is applicable across a broad spectrum of cryptographic implementations due to its reliance on correlating power consumption with data manipulation, rather than specific algorithmic weaknesses. Successfully targeting algorithms such as Advanced Encryption Standard (AES), RSA, and Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC) requires establishing a power model – typically Hamming Weight or Hamming Distance – and collecting sufficient power traces during cryptographic operations. The statistical analysis then attempts to recover secret keys by identifying correlations between the hypothesized intermediate values and the observed power consumption. While the specific implementation details of a DPA attack vary depending on the target algorithm and hardware platform, the core principle remains consistent, allowing for a unified attack methodology across diverse cryptographic systems.

EstraNet represents a class of recent Side-Channel Analysis (SCA) techniques designed for improved efficiency and scalability. Unlike traditional methods with potentially quadratic or higher complexity, EstraNet achieves a linear relationship between memory and time complexity with respect to the number of power traces analyzed. This linear scaling is accomplished through the use of a novel statistical approach that efficiently correlates power consumption with hypothesized data values, reducing computational burden and enabling analysis of larger datasets. Published results demonstrate EstraNet’s high accuracy in extracting secret keys from devices implementing cryptographic algorithms, positioning it as a significant advancement in practical SCA implementations. The technique’s efficiency makes it particularly suited for resource-constrained environments and large-scale deployments.

TransNet is a side-channel analysis technique characterized by its computational efficiency. Specifically, TransNet achieves linear time and memory complexity proportional to the number of power traces used in the analysis. This scalability is a significant advantage over some traditional methods, which may exhibit quadratic or higher-order complexity, especially when analyzing a large dataset of power consumption measurements. The linear relationship between resource usage and trace length enables TransNet to be applied to devices generating extensive power trace data without incurring prohibitive computational costs or memory requirements, facilitating practical implementation in a wider range of attack scenarios.

Remote Power Analysis (RPA) significantly broadens the potential attack surface against cryptographic implementations by removing the requirement for direct physical connection to the target device. Traditional Side-Channel Analysis (SCA) methods, including Differential Power Analysis (DPA), necessitate probes connected to the device to measure power consumption. RPA circumvents this limitation by utilizing remotely measurable electromagnetic emanations, which are correlated to the device’s internal operations. These emanations, captured through antennas or other non-invasive sensors, provide the necessary data for statistical analysis analogous to DPA. The feasibility of RPA depends on signal strength and noise levels, but it introduces a substantial risk as it eliminates the physical security barriers traditionally relied upon to protect cryptographic keys and sensitive data.

The Rise of the Machines: Automating the Attacks

Machine learning (ML) attacks in side-channel analysis leverage statistical classification algorithms to analyze power consumption, electromagnetic radiation, or timing variations during cryptographic operations. These attacks treat the side-channel leakage as a feature vector and employ techniques like support vector machines, decision trees, and neural networks to classify these traces. Successful classification allows an attacker to correlate specific trace patterns with the key or intermediate values being processed, ultimately leading to secret key recovery. The increasing prevalence of ML stems from its ability to automatically learn complex relationships within the data, often surpassing the performance of traditional signal processing techniques, and its adaptability to noisy or incomplete measurements. Furthermore, the automation facilitated by ML significantly reduces the expertise and time required to mount a successful side-channel attack.

Deep learning techniques demonstrate efficacy in side-channel analysis due to their capacity to automatically learn hierarchical representations from raw data, such as power traces or electromagnetic emanations. Unlike traditional methods that rely on handcrafted features and statistical assumptions, deep neural networks – specifically Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) – can identify subtle, non-linear relationships indicative of secret key usage. This is achieved through multiple layers of interconnected nodes that progressively extract increasingly abstract features, enabling the classification of traces with high accuracy even in the presence of noise and variations. The ability to learn these complex patterns without explicit feature engineering significantly reduces the effort required to mount successful side-channel attacks and improves their effectiveness against countermeasures designed to obscure information leakage.

Binarized Neural Networks (BNNs) represent a computationally efficient alternative to traditional deep learning models for side-channel analysis. BNNs achieve this efficiency by quantizing weights and activations to only two values – typically +1 and -1 – significantly reducing memory footprint and computational complexity. This binarization allows for the replacement of computationally expensive floating-point operations with bitwise operations, accelerating both training and inference. While some accuracy may be lost compared to full-precision networks, techniques like batch normalization and careful network architecture design mitigate this loss, making BNNs practical for resource-constrained environments and real-time side-channel attacks. The reduced computational demands of BNNs facilitate deployment on embedded devices and enable faster processing of large datasets of power traces, making them a valuable tool for automated side-channel analysis.

Automated side-channel analysis via machine learning addresses several limitations inherent in traditional methods. Manual analysis of power traces, timing variations, or electromagnetic emanations is time-consuming and requires significant expert knowledge to identify subtle patterns indicative of secret key material. Machine learning algorithms, once trained, can process large datasets of traces with minimal human intervention, significantly reducing analysis time and cost. Furthermore, traditional methods often struggle with noisy data or complex devices where signal characteristics are obscured; machine learning models, particularly deep learning architectures, demonstrate increased resilience to noise and can learn to extract meaningful information from highly complex signals that would be undetectable using conventional statistical techniques. This automation extends to identifying optimal attack parameters and adapting to variations in device implementations, providing a more robust and scalable approach to side-channel vulnerability assessment.

The survey meticulously details the escalating arms race between attack methodologies and defensive countermeasures. It’s a predictable cycle; each innovation in leakage assessment inevitably invites a refinement of the attack surface. This feels less like security and more like applied entropy. As Bertrand Russell observed, “The problem with the world is that everyone is an expert in everything.” The same applies here – everyone believes their countermeasure is sufficient until production finds the flaw. The article’s exploration of machine learning’s role only accelerates this; it’s simply chaos with better tooling. They don’t deploy – they let go.

What’s Next?

The surveyed landscape of power side-channel attacks and countermeasures reveals a familiar pattern. Sophisticated analytical techniques, including machine learning applications, consistently emerge to circumvent even the most meticulously designed defenses. One suspects the current enthusiasm for ‘robust’ countermeasures will, in time, resemble the fanfare surrounding differential power analysis in the early 2000s – a problem solved, then subtly reintroduced with each new silicon generation. The pursuit of perfect security remains an asymptotic approach.

Future efforts will likely focus on automating leakage assessment. The manual effort currently required to characterize vulnerabilities in complex cryptographic implementations is unsustainable. However, automated tools will inevitably optimize for the known leakage profiles, leaving ample room for novel attacks exploiting unforeseen interactions. The real challenge isn’t simply detecting existing leaks, but anticipating the unexpected consequences of increasingly intricate designs. If all automated tests pass, it probably means they’re measuring the wrong things.

Ultimately, the field appears destined to cycle through phases of attack, countermeasure, and subsequent re-attack. The fundamental limitation isn’t a lack of clever algorithms, but the inherent physical realities of computation. Every attempt to ‘hide’ information leaks something, and production systems, with their inevitable corner cases and optimizations, will always find creative ways to reveal it. The question isn’t if the next side-channel attack will succeed, but when and against which supposedly impenetrable barrier.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2512.23785.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Enshrouded: Giant Critter Scales Location

- All Carcadia Burn ECHO Log Locations in Borderlands 4

- Best Finishers In WWE 2K25

- Best ARs in BF6

- All Shrine Climb Locations in Ghost of Yotei

- Top 10 Must-Watch Isekai Anime on Crunchyroll Revealed!

- Poppy Playtime 5: Battery Locations & Locker Code for Huggy Escape Room

- Top 8 UFC 5 Perks Every Fighter Should Use

- Best Anime Cyborgs

- Keeping Agents in Check: A New Framework for Safe Multi-Agent Systems

2026-01-04 14:26