Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research explores how manipulating the band structure of IV-VI semiconductor quantum wells can unlock the Quantum Anomalous Hall Effect without the need for external magnetic fields.

Theoretical calculations demonstrate the potential for achieving quantized Hall conductance in specifically designed IV-VI semiconductor heterostructures through strain engineering and band topology control.

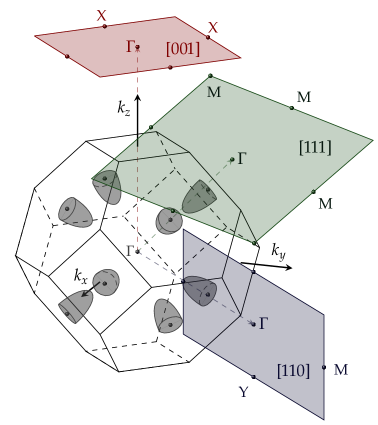

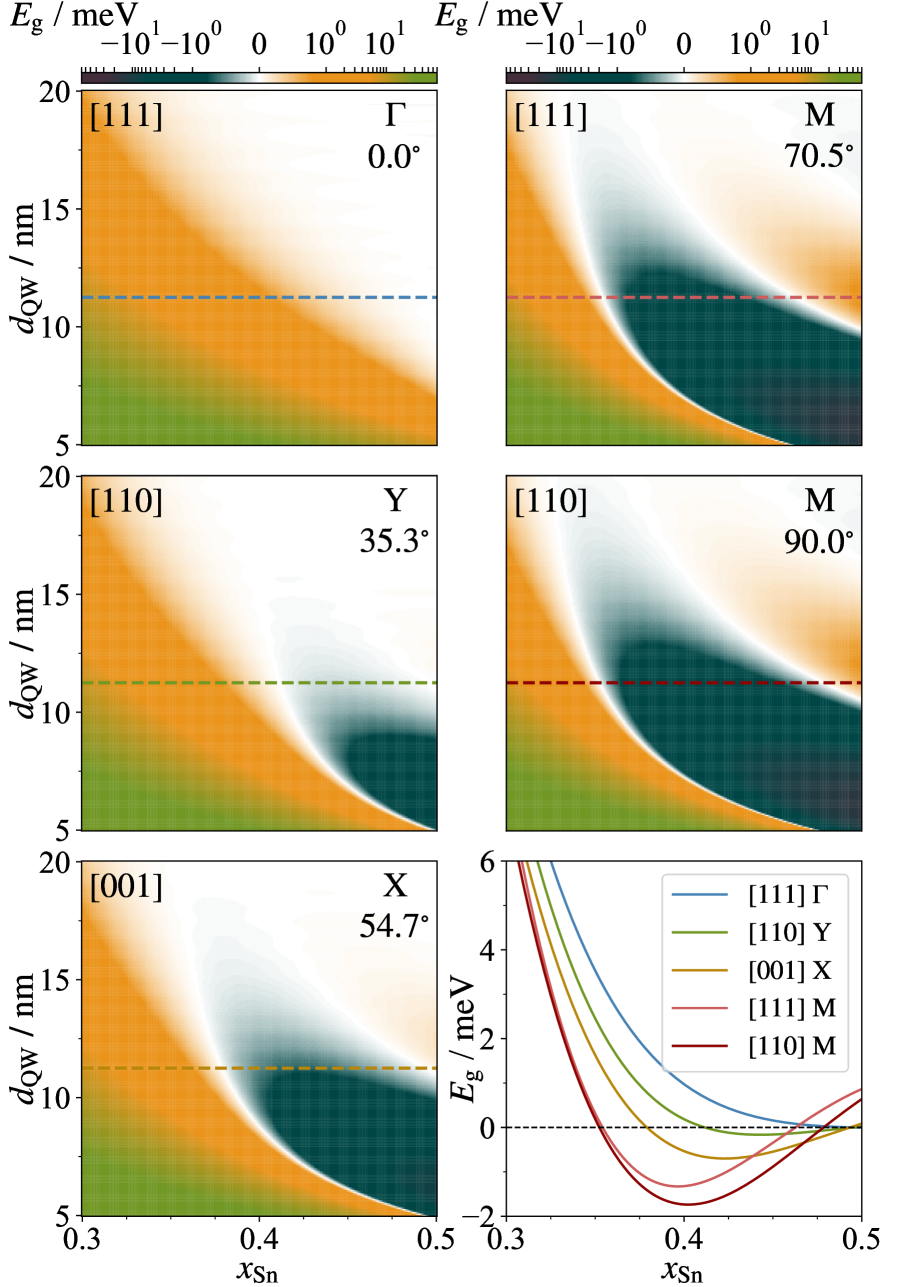

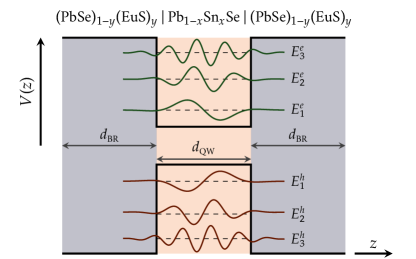

Realizing dissipationless electronic transport remains a central challenge in materials science, yet topological materials offer a promising pathway through the quantum anomalous Hall effect. This work, ‘From many valleys to many topological phases – quantum anomalous Hall effect in IV-VI semiconductor quantum wells’, theoretically investigates the potential of Pb$_{1-x}$Sn$_x$Se/(PbSe)$_{1-y}$(EuS)$_y$ quantum wells to host this effect, predicting attainable Chern numbers ranging from 1 to 4 depending on material composition and growth orientation. Band structure and \mathit{k} \cdot \mathit{p} Hamiltonian calculations reveal that careful strain compensation is crucial for achieving quantized Hall conductance in these systems. Could these findings pave the way for novel, low-power spintronic devices based on IV-VI semiconductor heterostructures?

The Relentless Pursuit of Topological Order

The Quantum Hall Effect (QHE), first observed decades ago in two-dimensional electron systems subjected to intense magnetic fields, has profoundly impacted both metrology and fundamental physics. This remarkable phenomenon quantizes the Hall resistance – the voltage measured perpendicular to both current and magnetic field – into precise, discrete values determined solely by fundamental constants and the strength of the magnetic field. This quantization provides an exceptionally accurate standard for electrical resistance, far surpassing traditional methods, and is utilized globally in national metrology labs. Beyond precision measurement, the QHE has served as a crucial testing ground for condensed matter theories, revealing exotic quasiparticles with fractional charge and furthering understanding of topological phases of matter. The effect’s robustness and accuracy continue to inspire the development of novel electronic devices and offer insights into the quantum realm, despite the practical limitations imposed by the need for powerful magnets and low temperatures.

The pursuit of the Quantum Anomalous Hall Effect (QAHE) – a state mirroring the Quantum Hall Effect but crucially without the need for externally applied magnetic fields – is substantially hampered by the limited availability of suitable materials. Unlike conventional Quantum Hall systems achievable in readily available two-dimensional electron gases, the QAHE demands materials with specific band structures and nontrivial topological properties. These materials must intrinsically break time-reversal symmetry, a condition difficult to satisfy without external magnetic fields or complex material engineering. Current research faces hurdles in finding compounds that exhibit a robust QAHE at accessible temperatures, as many promising candidates either lack the necessary topological protection or require extreme conditions to observe the effect, thereby restricting their practical application and hindering further exploration of this fascinating quantum phenomenon.

The pursuit of the Quantum Anomalous Hall Effect (QAHE) without reliance on external magnetic fields has directed materials science toward the investigation of topological insulators and intricately designed heterostructures. These materials, possessing unique electronic properties stemming from their band structure topology, offer a pathway to realize intrinsic QAHE states. Researchers are focusing on combining different materials-creating heterostructures-to engineer the necessary band alignment and broken time-reversal symmetry crucial for QAHE observation. This involves careful material selection and interface control, as the electronic properties are highly sensitive to atomic-scale details. The successful development of such materials promises not only fundamental advances in condensed matter physics but also potential applications in spintronics and low-power electronics, offering devices with dissipationless edge states and robust performance.

![Calculated band dispersions <span class="katex-eq" data-katex-display="false">E_{b}^{e,h}(\bm{k})</span> and probability densities <span class="katex-eq" data-katex-display="false">|\Psi_{b}^{e,h}(z)|^{2}</span> reveal that increasing tin content from 0.1 to 0.5 in a [001]-oriented quantum well induces spatially localized surface states at the well boundaries and a gapped, nearly linear Dirac-cone dispersion.](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.16137v1/x9.png)

Unveiling the Topology: The Foundation of Robust States

Topological insulators (TIs) are materials characterized by conducting surface states despite possessing an insulating bulk. These surface states are a direct consequence of strong spin-orbit coupling and are topologically protected by time-reversal symmetry, meaning they are robust against non-magnetic impurities and defects. This protection arises from the materials’ unique band structure, where the bulk band gap closes and reopens, leading to the formation of these conducting surface states. The preservation of time-reversal symmetry is critical; magnetic perturbations can lift the protection and open a gap in the surface states. Consequently, TIs are actively researched as potential platforms for realizing the Quantum Anomalous Hall Effect (QAHE), where dissipationless edge currents can flow without the need for an external magnetic field, provided time-reversal symmetry is broken in a controlled manner.

Band inversion is the fundamental process by which topological insulators (TIs) achieve their unique electronic properties. Traditionally, materials exhibit a clear ordering of valence and conduction bands based on energy; however, in TIs, the conduction and valence bands can reverse their typical ordering at specific momenta in the Brillouin zone. This reversal doesn’t simply alter energy levels, but fundamentally changes the topology of the electronic band structure, creating non-trivial \mathbb{Z}_2 invariants. The resulting band structure supports conducting surface states that are topologically protected-meaning they are robust against non-magnetic disorder-and are responsible for the unusual conductive properties observed in these materials. The degree of band inversion is directly correlated with the strength of the topological protection and the nature of the surface states.

The topological properties of materials, specifically their classification as topological insulators, are mathematically defined by topological invariants, with the Chern number being a primary descriptor of the material’s band structure. This study demonstrates, through theoretical modeling, that manipulating material composition and applying external magnetic fields can control the Chern number, achieving values up to 4. The Chern number, an integer representing the winding of the Berry curvature in momentum space, directly correlates to the number of chiral edge states present in the material, and thus its potential for applications requiring robust, dissipationless electron transport. Achieving higher Chern numbers, like those demonstrated in this research, represents a pathway toward more complex and potentially more functional topological devices.

![The Chern number phase diagram was assembled by superimposing Chern number values calculated across a <span class="katex-eq" data-katex-display="false">13 \times 13</span> grid for each projection of the <span class="katex-eq" data-katex-display="false">L</span> valleys onto the two-dimensional Fermi Brillouin Zone (FBZ) in a [111] quantum well with a barrier magnetization coefficient of <span class="katex-eq" data-katex-display="false"> \eta = 0.2</span>.](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.16137v1/x12.png)

Architecting Magnetism: A Path to Symmetry Breaking

The Quantum Anomalous Hall Effect (QAHE) requires a broken time-reversal symmetry, which is typically achieved by introducing magnetism into topological insulators. This is commonly accomplished through the creation of heterostructures – layered materials combining a topological insulator with a magnetically ordered material. The magnetic ordering, characterized by an internal magnetization vector, effectively lifts the spin degeneracy of the topological surface states. This lifting creates a net topological magnetization, leading to the quantized anomalous Hall conductance without the need for an external magnetic field. The magnitude of the anomalous Hall conductance is directly related to the magnetization of the magnetic layer and the strength of the coupling between the magnetic material and the topological insulator’s surface states.

Europium sulfide (EuS) and europium selenide (EuSe) are utilized as magnetic barrier layers in heterostructure designs to induce magnetism without compromising the topological protection of the quantum anomalous Hall effect (QAHE). These materials exhibit ferromagnetic ordering at relatively low temperatures, providing the necessary exchange coupling to break time-reversal symmetry in adjacent topological insulators. Importantly, EuS and EuSe possess a rock-salt crystal structure that facilitates epitaxial growth and minimizes interfacial scattering, thereby preserving the Dirac surface states crucial for topological conductivity. The effectiveness of these materials stems from their ability to introduce long-range magnetic order while maintaining a reasonably well-defined interface with the topological insulator, avoiding significant disruption of the electronic band structure.

The realization of high-quality heterostructures for the Quantum Anomalous Hall Effect (QAHE) necessitates meticulous material selection, prioritizing lattice matching to minimize interfacial defects and preserve the topological surface states. Materials exhibiting the rock-salt crystal structure, such as PbSe and SnSe, are frequently employed due to their compatibility and predictable growth characteristics. Strain induced by lattice mismatch directly impacts the electronic band structure; specifically, the band gap shift ( \Delta E_g ) is quantifiable and directly related to the applied or inherent strain (ε) as defined by the equations presented in reference (51). These equations detail the specific parameters governing the band gap modification, allowing for precise engineering of the heterostructure’s electronic properties and optimization for QAHE observation.

![Strain modulation in a [111]-oriented quantum well-with <span class="katex-eq" data-katex-display="false">x_{Sn} = 0.49</span> and <span class="katex-eq" data-katex-display="false">d_{QW} = 5\,\mathrm{nm}</span>-allows for control of band-edge alignment and expulsion of longitudinal valley states from topological gaps, even without magnetic doping.](https://arxiv.org/html/2601.16137v1/x10.png)

Refining the Landscape: Perturbation Theory and Precision Engineering

Lattice mismatch between materials forming a heterostructure introduces strain due to differing atomic spacings. This strain directly modifies the electronic band structure by perturbing the periodic potential experienced by electrons, affecting parameters such as band gap and effective mass. Significant strain can disrupt the delicate balance required for topological phases of matter, potentially closing topological band gaps or altering topological invariants. The magnitude of this effect is dependent on the degree of lattice mismatch, the materials’ Poisson ratio, and the dimensionality of the heterostructure; larger mismatches and lower dimensionality generally lead to more substantial band structure alterations and a greater risk of compromising topological properties.

Deformation potential theory and Vegard’s Law are utilized to quantitatively assess and manage the impact of strain on material properties. Deformation potential theory establishes a relationship between applied strain and the resulting change in band edges, allowing for prediction of band gap shifts and effective mass alterations due to lattice mismatch. Vegard’s Law provides a linear interpolation of lattice parameters based on composition in alloy semiconductors; deviations from this law indicate strain within the material. These techniques enable the calculation of critical thickness for heterostructures, beyond which strain relaxation via dislocation formation becomes likely, and facilitate the design of strain-engineered devices by pre-determining the required layer thicknesses and compositions to achieve desired band structure modifications.

k⋅p perturbation theory provides a method for accurately calculating the band structure of semiconductor heterostructures by treating deviations from a known band structure as small perturbations. This approach is essential for optimizing material combinations and device designs, as it allows prediction of electronic properties without full, computationally expensive ab initio calculations. Specifically, the theory enables precise determination of band offsets, effective masses, and other critical parameters that influence device performance. The temperature dependence of the band gap, a key factor in many semiconductor applications, is formally defined by equations E_g(T) = E_g(0) - \alpha T^2 / (T + \theta_c) (equation 54) and \alpha = \frac{V_c - V_v}{T} (equation 55), where E_g is the band gap, T is the temperature, α is the temperature coefficient, and \theta_c represents the Debye temperature.

Beyond the Horizon: Implications for Quantum Technologies

The emergence of the Quantum Anomalous Hall Effect (QAHE) in materials such as bismuth-antimony-tellurium (BiSbTe) and meticulously crafted multilayer graphene signifies a potential revolution in electronics. Unlike conventional materials where electron flow inevitably encounters resistance, these QAHE materials exhibit dissipationless edge channels – pathways where electrons travel without losing energy. This remarkable property arises from the unique topological state of these materials, protecting electron flow from scattering and imperfections. Consequently, these channels promise ultra-efficient electronic devices, drastically reducing energy consumption and heat generation. The development paves the way for smaller, faster, and more sustainable electronics, potentially enabling entirely new classes of devices that were previously limited by energy constraints and material inefficiencies.

The pursuit of increasingly efficient and adaptable quantum anomalous Hall effect (QAHE) systems hinges on innovative material science. Researchers are actively investigating unconventional combinations of materials and meticulously engineered heterostructures – layering different materials with atomic precision – to optimize the QAHE. This approach aims to not only enhance the strength of the effect, leading to more robust dissipationless edge channels, but also to provide greater control over its properties. By carefully selecting materials with complementary electronic structures and tailoring the interfaces between them, scientists hope to fine-tune the Fermi level and magnetic ordering, ultimately creating QAHE systems that are more easily integrated into practical devices and can operate at higher temperatures, paving the way for breakthroughs in quantum computing and spintronics.

The emergence of robust quantum phenomena, such as the Quantum Anomalous Hall Effect, extends far beyond fundamental materials science, holding considerable promise for revolutionizing several burgeoning technological fields. Quantum computing stands to benefit from the dissipationless edge channels created by these effects, potentially enabling the creation of more stable and efficient qubits. Similarly, spintronics – a field leveraging electron spin for data storage and processing – could experience breakthroughs through enhanced spin polarization and transport properties. Beyond these, other emerging quantum technologies, including advanced sensors and novel communication methods, are poised to capitalize on the unique characteristics of these materials, paving the way for devices with unprecedented performance and functionality. This intersection of materials science and quantum engineering signals a paradigm shift, hinting at a future where quantum effects are not confined to the laboratory, but integrated into everyday technologies.

The exploration of IV-VI semiconductor quantum wells, as detailed in this research, inherently acknowledges the transient nature of even the most meticulously constructed systems. Every manipulation of band structure, every application of strain engineering, is a temporary measure against the inevitable drift towards entropy. As Albert Camus observed, “The struggle itself…is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.” This sentiment resonates with the core concept of topological phases; the quantized Hall conductance isn’t a static endpoint, but a fleeting moment of order achieved through deliberate intervention – a persistent, if ultimately temporary, defiance of decay. The research suggests a path toward realizing this order, recognizing, implicitly, that even architectural marvels, be they physical or theoretical, are subject to the passage of time.

The Horizon Beckons

The proposition that robust topological phases can emerge within IV-VI semiconductor quantum wells, divorced from the strictures of external magnetic fields, reveals less a destination than a deepening of the inquiry. Every failure to achieve quantization-every deviation from the ideal Chern number-is a signal from time, a reminder that material reality is not a Platonic form but a landscape of imperfections. The sensitivity to strain engineering, while offering a pathway to control, simultaneously highlights the fragility inherent in these states; a testament to the inevitable decay of order.

Future iterations will undoubtedly focus on the practical realization of these theoretical predictions. However, the true challenge lies not merely in fabrication, but in understanding the limits of predictability. The band structure calculations, however sophisticated, are snapshots in a dynamic system. The interplay of defects, interfaces, and thermal fluctuations represents a complexity that resists complete capture. Refactoring the material composition is a dialogue with the past, attempting to anticipate the entropy of the future.

The pursuit of zero-field topological states is, in essence, a meditation on stability. It is not a quest for permanence-for such a thing does not exist-but for gracefully extended lifetimes. The question is not whether these states will ultimately decay, but how long they can resist the inevitable return to equilibrium, and what lessons their disintegration will offer.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.16137.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Enshrouded: Giant Critter Scales Location

- How to Unlock & Visit Town Square in Cookie Run: Kingdom

- Best Finishers In WWE 2K25

- Poppy Playtime 5: Battery Locations & Locker Code for Huggy Escape Room

- Top 8 UFC 5 Perks Every Fighter Should Use

- All Carcadia Burn ECHO Log Locations in Borderlands 4

- Best ARs in BF6

- Top 10 Must-Watch Isekai Anime on Crunchyroll Revealed!

- Best Anime Cyborgs

- All Shrine Climb Locations in Ghost of Yotei

2026-01-24 16:08