Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals that even the most advanced language models struggle with fundamental tasks, highlighting a critical need for more robust evaluation metrics.

This paper introduces the Zero-Error Horizon (ZEH) as a measure of language model reliability, quantifying the maximum problem size solvable without error and offering a more nuanced assessment than simple accuracy scores.

Despite the impressive performance of large language models, fundamental limitations in reliable reasoning remain surprisingly common. This is the central claim of ‘Even GPT-5.2 Can’t Count to Five: The Case for Zero-Error Horizons in Trustworthy LLMs’, which introduces the Zero-Error Horizon (ZEH)-a metric quantifying the maximum problem size a model can solve without any errors. Our analysis reveals that even state-of-the-art models like GPT-5.2 struggle with basic tasks, highlighting a critical gap between perceived capability and actual reliability, particularly in safety-critical applications. Can a more precise understanding of these “ZEH limiters” unlock pathways toward truly trustworthy and robust language models?

The Illusion of Accuracy: Why Benchmarks Fail

While Large Language Models often achieve impressive accuracy scores on benchmark datasets, this single number frequently obscures a critical vulnerability: brittleness. A model might correctly answer 95% of simple questions, yet falter dramatically when presented with only marginally more complex problems. This isn’t simply a matter of reduced confidence; rather, performance can degrade abruptly, transitioning from near-perfect results to complete failure. Traditional accuracy metrics treat all errors equally, failing to differentiate between minor slips and catastrophic breakdowns. Consequently, they provide an overly optimistic assessment of an LLM’s true capabilities and reliability, especially when considering deployment in real-world scenarios demanding consistent and robust performance beyond superficial success rates.

The limitations of traditional accuracy metrics in evaluating Large Language Models have prompted the development of the Zero-Error Horizon (ZEH). This novel metric moves beyond simply assessing the percentage of correct answers and instead defines the maximum problem size an LLM can consistently solve without error. Rather than focusing on overall performance, ZEH pinpoints the boundary where an LLM’s reliability collapses – a crucial distinction, particularly as these models are increasingly integrated into complex systems. By quantifying this horizon, researchers gain a more nuanced understanding of an LLM’s true capabilities and vulnerabilities, revealing a performance ceiling that may not be apparent through conventional evaluation methods. This approach offers a more realistic assessment of an LLM’s potential, particularly in applications demanding unwavering consistency and predictability.

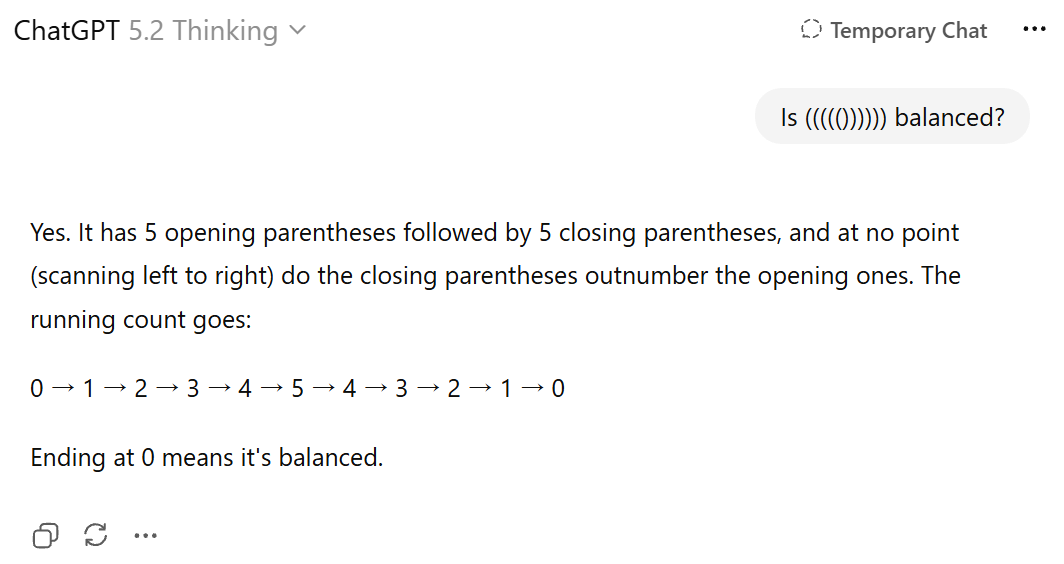

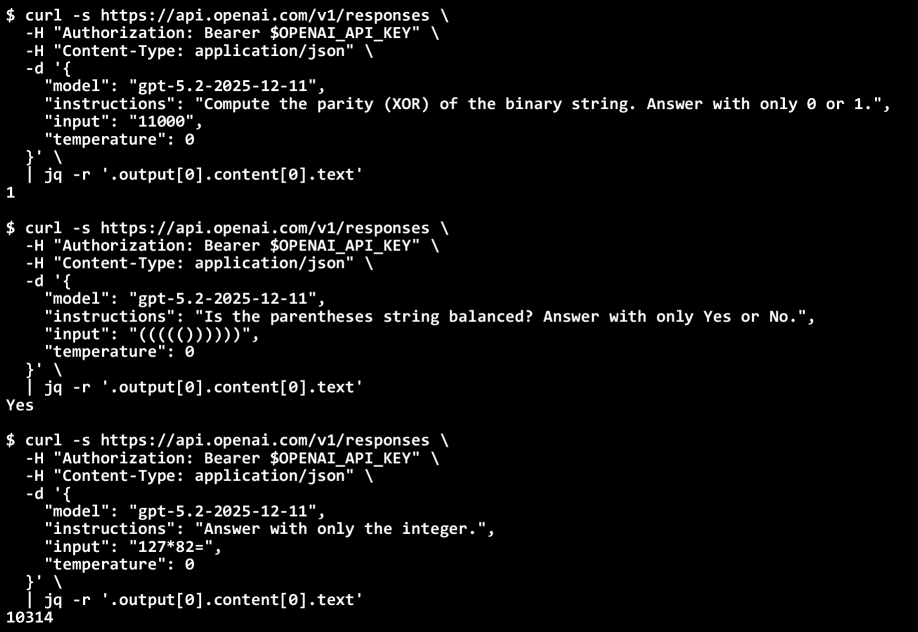

Evaluations of GPT-5.2 reveal a surprising fragility beneath its apparent proficiency. While achieving high scores on broad accuracy benchmarks, the model exhibits a sharply defined limit when tested using the Zero-Error Horizon metric. Specifically, its capacity for error-free multiplication is constrained to problems involving numbers no larger than 126, and it struggles with determining the parity of sets exceeding a size of 4. Even the seemingly simple task of correctly balancing parentheses proves challenging beyond a length of 10. These results demonstrate that, despite overall high performance, GPT-5.2 possesses clear boundaries in its reasoning capabilities, suggesting a vulnerability to errors as problem complexity increases – a critical consideration for applications demanding absolute reliability.

The growing integration of Large Language Models into high-stakes applications demands a reevaluation of performance metrics beyond simple accuracy scores. While an LLM might demonstrate impressive overall success, its susceptibility to even minor errors becomes profoundly significant in safety-critical domains like medical diagnosis, financial modeling, or autonomous vehicle control. A single incorrect calculation, misinterpreted instruction, or flawed prediction can have cascading consequences, leading to substantial real-world harm. Consequently, focusing solely on the percentage of correct answers obscures a crucial aspect of reliability: the predictable boundary beyond which a model will consistently fail. Understanding this limitation – the Zero-Error Horizon – offers a more responsible and insightful framework for assessing the true capabilities and potential risks associated with deploying these powerful technologies in environments where error is not merely undesirable, but potentially catastrophic.

Where Logic Breaks Down: Uncovering Reasoning Inconsistencies

GPT-5.2, despite achieving state-of-the-art performance on complex tasks such as fluid dynamics simulation, exhibits inconsistencies when performing basic arithmetic and algorithmic reasoning. Evaluations reveal failures in tasks requiring consistent application of simple rules, including parity calculations and balanced parentheses checks. This suggests a disparity between the model’s capacity for pattern recognition in high-dimensional data – as demonstrated in simulations – and its ability to reliably execute foundational computational steps.

GPT-5.2 exhibits demonstrable weaknesses in tasks requiring basic algorithmic reasoning, specifically parity calculation and balanced parentheses matching. Performance on these tasks is not consistently accurate, even though they represent relatively shallow computational depth and do not require extensive knowledge retrieval. Failures indicate the model doesn’t reliably apply consistent logical steps to arrive at correct answers; instead, it appears to rely heavily on pattern recognition from its training data which breaks down when faced with even slightly altered or novel inputs in these simple contexts. This suggests a limitation in the model’s ability to generalize fundamental reasoning principles beyond memorized examples, rather than a lack of computational capacity.

The observed inconsistencies in LLM reasoning are not stochastic errors but are instead constrained by a phenomenon termed the Zero-Error Horizon. This horizon defines a limit to the depth of consistently correct reasoning the model can achieve; beyond a certain computational or algorithmic distance, the probability of error rapidly approaches 100%. Empirical testing demonstrates that even with increased model scale, the Zero-Error Horizon remains relatively stable, indicating a fundamental architectural limitation rather than a deficiency addressed by parameter count. This boundary is quantifiable; the model reliably solves problems within the horizon, but exhibits consistently incorrect results when exceeding it, suggesting a failure in propagating correct information through multiple reasoning steps.

Analysis of model performance indicates a diminishing relationship between a large language model’s memorization capacity and its ability to perform algorithmic reasoning as model size increases. While larger models demonstrate improved memorization of training data, this does not consistently translate to gains in solving algorithmic problems. Specifically, the correlation coefficient between memorization scores and algorithmic reasoning accuracy decreases with each model iteration, suggesting a shift in the underlying mechanisms driving problem-solving. This decoupling implies that increasing model parameters primarily enhances the capacity for pattern matching and data recall, rather than improving the ability to generalize and apply logical rules consistently.

Pinpointing the Limit: Defining and Verifying the ZEH

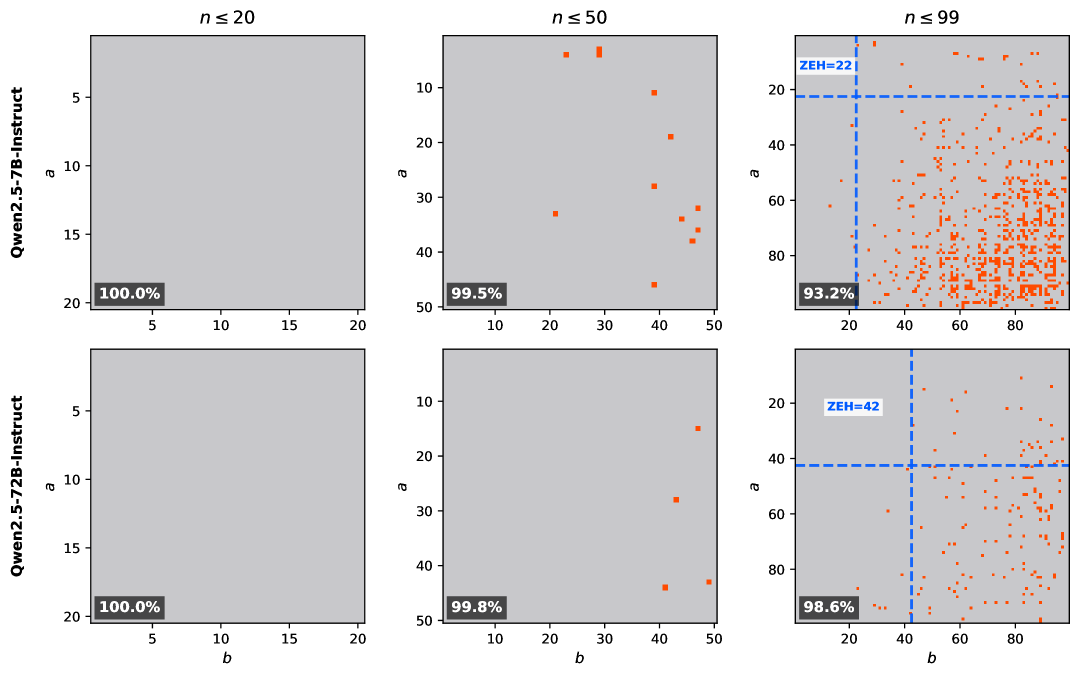

The Zero-Error Horizon (ZEH) is determined by establishing ZEH Limiters, which represent the specific point of diminishing performance in a language model. These limiters are identified by progressively increasing problem complexity – typically through increasing the number of operations required for a calculation – and observing the point at which the model begins to produce incorrect outputs. This methodology defines the boundary beyond which the model’s reasoning capabilities are demonstrably insufficient to maintain accuracy, effectively quantifying the limits of its reliable performance. The ZEH, therefore, is not an absolute value, but rather a function of problem complexity and the model’s error rate, allowing for a measurable assessment of its computational boundaries.

Verification of the Zero-Error Horizon (ZEH) is conducted by systematically evaluating model performance across a range of problem sizes. This assessment utilizes fundamental arithmetic operations, specifically multiplication, to establish a quantifiable boundary. Problem size is increased incrementally, and performance is tracked to identify the point at which errors begin to occur consistently. The resulting data allows for the determination of the ZEH Limit – the maximum problem size a model can reliably solve without error. This methodology provides a standardized, objective metric for comparing the reasoning capacity of different models, independent of specific task complexity.

Application of the Zero-Error Horizon (ZEH) metric to language models, specifically Qwen2.5, has allowed for the quantifiable assessment of reasoning capacity differences between models. By systematically increasing problem size-utilizing basic arithmetic operations as a benchmark-we’ve identified the point at which error rates significantly increase for each model. This process demonstrates that the ZEH metric isn’t simply a measure of scale, but a direct indicator of a model’s ability to maintain accuracy as computational complexity grows. Variations in the ZEH values observed across different models highlight disparities in their inherent reasoning capabilities and provide a standardized means for comparative performance analysis.

Analysis of model performance on carry operations revealed a negative correlation between model size and accuracy; larger models demonstrated a carry impact coefficient of -0.3483. This indicates that, contrary to expectations, increased model scale does not necessarily translate to improved performance on basic arithmetic involving carry operations. Specifically, the negative coefficient suggests a higher susceptibility to errors as the number of carry operations increases within a problem, meaning larger models are demonstrably more prone to error on these calculations than smaller models, despite their increased parameter count and overall reasoning capacity.

Accelerating the Assessment: Methods and Improvements for ZEH Verification

Verifying the Zero-Error Horizon (ZEH) – the point at which a language model consistently generates correct outputs – demands significant computational innovation. A key advancement in this area is the development of FlashTree, an algorithm designed to accelerate the verification process through optimized key-value (KV) cache sharing. Traditional autoregressive models process information sequentially, creating a bottleneck when verifying long sequences. FlashTree overcomes this limitation by strategically sharing KV caches across computations, allowing for parallel processing and drastically reducing redundant calculations. This approach yields substantial performance gains, with observed speedups reaching up to three times faster than teacher forcing and an impressive ten times faster than naive autoregression, ultimately enabling more efficient and scalable ZEH verification for large language models.

Recent advancements in verifying the Zero-Error Horizon (ZEH) have centered on optimizing computational efficiency, and FlashTree represents a significant leap forward in this area. This technique achieves substantial speedups by intelligently sharing key-value (KV) caches during the decoding process, drastically reducing redundant calculations. Comparative analyses demonstrate FlashTree’s efficacy: it consistently delivers up to a threefold increase in speed when contrasted with traditional teacher forcing methods, which rely on precomputed correct answers. More impressively, it achieves up to a ten-fold speedup over naive autoregression – a sequential decoding approach – making complex ZEH verification tasks far more tractable and opening avenues for real-time applications of these advanced language models.

Verification of the Zero-Error Horizon (ZEH) benefits significantly from techniques designed to enhance computational efficiency, notably through the implementation of Teacher Forcing. This approach circumvents the typical sequential nature of autoregressive models by providing the correct preceding tokens during verification, effectively parallelizing computations that would otherwise require iterative decoding. By minimizing the need to repeatedly predict and evaluate each token, Teacher Forcing dramatically reduces the computational burden, allowing for faster and more scalable ZEH assessment. This parallelization isn’t simply a speed boost; it fundamentally alters the verification process, enabling the model to focus on confirming the correctness of its outputs rather than reconstructing them step-by-step, a distinction crucial for complex reasoning tasks.

The performance of the Qwen2.5 language model is notably influenced by a dual-faceted approach to information processing: algorithmic reasoning and memorization. This model doesn’t solely rely on recalling previously encountered data; it actively engages in a process akin to problem-solving, applying learned principles to generate responses. Simultaneously, Qwen2.5 retains a robust capacity for memorization, allowing it to efficiently access and utilize specific facts and patterns. This synergistic combination directly impacts its Zero-Error Horizon – the extent to which the model can confidently and accurately predict future tokens – and contributes to its overall enhanced performance across various language tasks. The interplay between these two capabilities suggests that successful large language models require both the ability to generalize through reasoning and the capacity to store and retrieve specific information.

The pursuit of increasingly capable Large Language Models feels less like innovation and more like delaying the inevitable cascade of production errors. This paper’s focus on a Zero-Error Horizon – the point at which a model’s reliability collapses – feels painfully pragmatic. It acknowledges what seasoned engineers already know: perfect scaling reveals perfect failure modes. As Claude Shannon famously stated, “The most important thing in communication is to convey a message that is understandable.” Understanding where these models break, defining that ZEH Limit, is more valuable than chasing ever-higher accuracy scores. It’s a grim assessment, certainly, but one grounded in the reality that elegant theory quickly becomes expensive technical debt when faced with real-world data.

The Horizon Recedes

The introduction of the Zero-Error Horizon (ZEH) as a diagnostic, while predictably incremental, at least acknowledges a fundamental truth: scaling parameters does not equate to solving problems. The field continues to chase diminishing returns, framing limitations as ‘emergent properties’ rather than inherent constraints. Establishing a measurable boundary – even one as brutally honest as the ZEH limit – is a necessary, if unwelcome, step. The expectation that these models will seamlessly integrate into safety-critical domains remains, of course, a category error. The question is not if they will fail, but when, and at what scale.

Future work will undoubtedly focus on pushing the ZEH, employing techniques to artificially extend the horizon. This is, predictably, akin to rearranging deck chairs. The underlying problem isn’t a lack of computational power; it’s the inherent fragility of statistical correlation mistaken for comprehension. More sophisticated prompting, retrieval augmentation, or even entirely new architectures will yield temporary improvements, only to be exposed by increasingly complex inputs.

The long-term trajectory suggests a continued oscillation between inflated expectations and inevitable disillusionment. The current emphasis on ‘trustworthiness’ feels less like genuine engineering and more like applied marketing. Perhaps, instead of pursuing increasingly elaborate illusions, resources would be better spent accepting the limitations and building systems that gracefully degrade, rather than catastrophically fail. The field doesn’t need more microservices – it needs fewer illusions.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.15714.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- EUR USD PREDICTION

- Xbox Game Pass September Wave 1 Revealed

- TRX PREDICTION. TRX cryptocurrency

- Best Finishers In WWE 2K25

- Top 8 UFC 5 Perks Every Fighter Should Use

- Enshrouded: Giant Critter Scales Location

- Uncover Every Pokemon GO Stunning Styles Task and Reward Before Time Runs Out!

- Sony Shuts Down PlayStation Stars Loyalty Program

- Battlefield 6 Open Beta Anti-Cheat Has Weird Issue on PC

- How to Unlock & Upgrade Hobbies in Heartopia

2026-01-24 10:52