Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals how strong electron correlation can disrupt the formation of robust integer quantum Hall states, impacting their potential for future electronic devices.

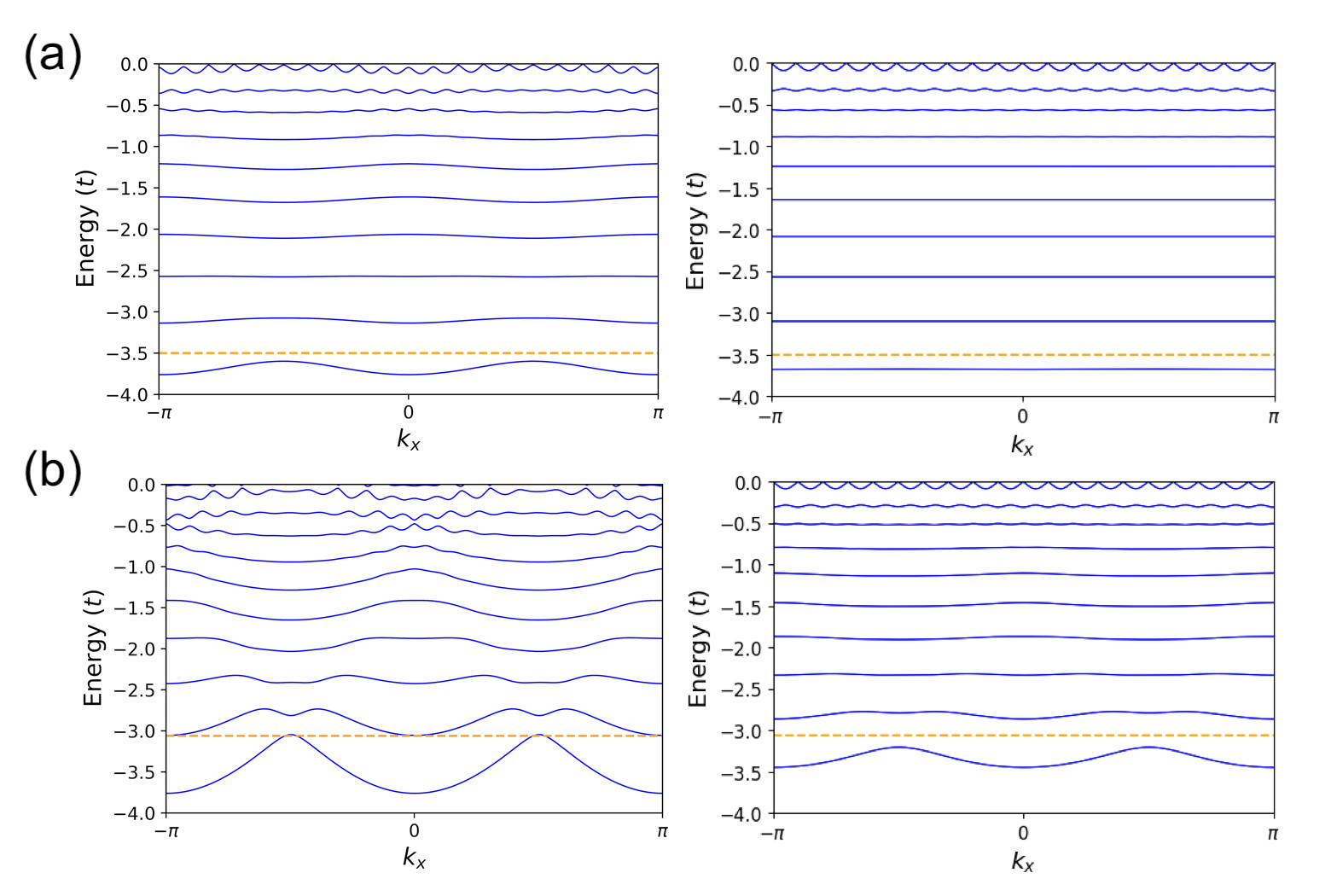

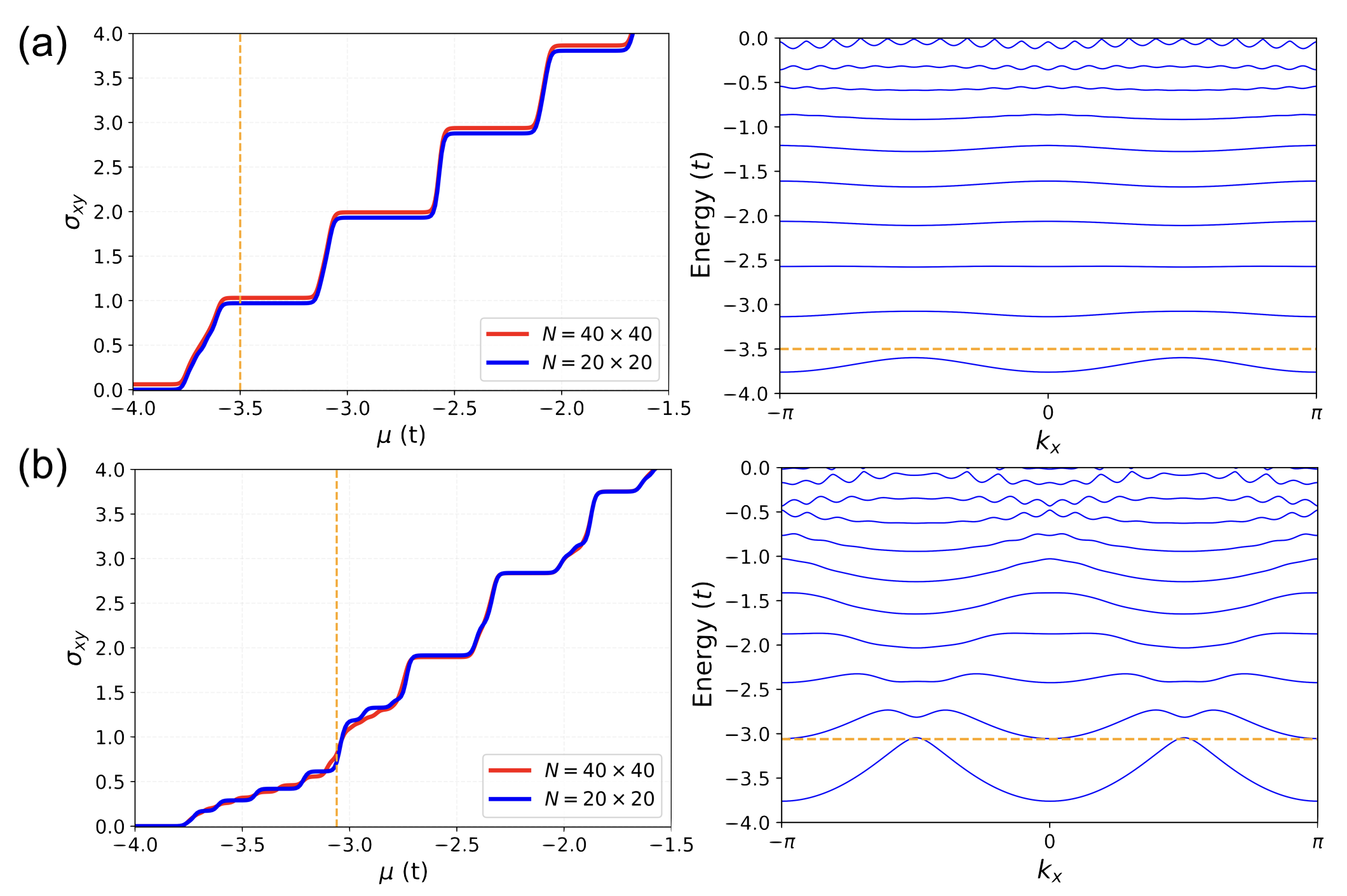

Band renormalization induced by spatial modulation of the electronic structure closes the mobility gap between Landau levels, degrading the integer quantum Hall effect.

The robustness of the integer quantum Hall effect, typically understood through single-particle models, is challenged by the inherent interactions between electrons in real materials. This research, titled ‘Effect of Electron Correlation on the Integer Quantum Hall Effect’, numerically investigates how increasing electron correlation-parameterized by the onsite repulsion U-degrades the quantization of transverse conductance in a square lattice. Our findings demonstrate that correlation effects induce periodic modulations in hopping parameters and site energies, ultimately closing the mobility gap between Landau levels and impacting conductivity in this topological phase. Could a more complete understanding of these correlation-driven band renormalizations pave the way for designing novel quantum Hall devices with enhanced stability and functionality?

The Topology of Robustness: A System’s Foundation

The Integer Quantum Hall Effect represents a striking example of topological order, a state of matter characterized not by broken symmetry, but by global properties that are robust against local perturbations. In this phenomenon, observed in two-dimensional electron systems subjected to strong magnetic fields and low temperatures, the Hall conductivity becomes precisely quantized in integer multiples of e^2/h, where e is the elementary charge and h is Planck’s constant. This quantization isn’t merely a consequence of precise control over material properties; it’s a protected state, stemming from the system’s topology – a property related to its connectivity rather than its detailed composition. This topological protection means the effect persists even with imperfections present, distinguishing it from many other quantum phenomena and highlighting its potential for robust quantum technologies. The effect showcases that certain physical properties aren’t dictated by local details, but by the global, inherent structure of the material, offering a pathway towards highly stable and reliable electronic devices.

The Quantum Hall Effect emerges from the peculiar behavior of electrons confined to a two-dimensional plane and subjected to intense magnetic fields. Under these conditions, the energy spectrum doesn’t continue as a smooth band, but instead organizes into discrete levels known as Landau Levels. These levels are remarkably degenerate, meaning a vast number of electrons can occupy each level with the same energy. This high degeneracy is crucial; it arises because of the quantized nature of electron motion in a magnetic field, where electrons are forced into cyclotron orbits. The more intense the magnetic field, the stronger the quantization and the more pronounced the Landau Level formation, creating the foundational conditions for the robust quantization of Hall conductivity observed in the effect. \omega_c = \frac{eB}{m} describes the cyclotron frequency, where e is the electron charge, B is the magnetic field, and m is the effective mass of the electron.

The exquisite quantization observed in the Quantum Hall Effect is notoriously sensitive to the realities of material composition. While ideal theoretical models predict perfect plateaus in transverse conductivity, actual two-dimensional electron gases invariably contain imperfections – collectively termed site disorder – that disrupt this delicate balance. These imperfections, arising from variations in the potential landscape due to impurities or defects, scatter electrons and broaden the normally sharply defined Landau Levels. Unlike the subtle electron correlations that can protect certain states, site disorder typically degrades all energy levels, increasing the likelihood of conductivity fluctuations and potentially destroying the quantized Hall plateaus. This widespread degradation presents a significant challenge to realizing robust Quantum Hall devices, demanding careful material engineering and a deep understanding of disorder’s impact on electron behavior.

The Illusion of Independence: Modeling Interacting Electrons

The Hubbard Model is a simplified representation of interacting electrons in a solid, specifically designed to address the limitations of single-particle band theory which neglects electron-electron interactions. It considers electrons moving on a lattice, typically a square lattice, and introduces two key parameters: t, representing the kinetic energy of hopping between lattice sites, and U, representing the on-site Coulomb repulsion between electrons occupying the same site. This model reduces the many-body problem to a more tractable form while retaining the essential physics of electron correlation effects, allowing for investigation of phenomena like Mott insulators and magnetism that arise from strong electron-electron interactions. The Hubbard Model serves as a foundational framework for understanding strongly correlated electron systems in condensed matter physics.

Electron correlation, arising from the Coulomb repulsion between electrons, fundamentally alters the band structure of a square lattice beyond the single-particle picture. In materials where electrons are not independent, these interactions lead to a renormalization of the electronic bands, reducing the effective mass of charge carriers and potentially inducing insulating behavior even in systems with partially filled bands. Specifically, the kinetic energy of an electron is no longer simply proportional to the wavevector k, but is modified by the presence of other electrons. This manifests as a narrowing of the bandwidth and the emergence of Hubbard bands, which are localized electronic states resulting from strong on-site Coulomb repulsion. The extent of this modification depends on the strength of the electron-electron interactions relative to the bandwidth, defining the material’s position within the Mott insulator or metallic phase.

The Gutzwiller approximation addresses the many-body problem inherent in the Hubbard model by assuming that electron configurations are uncorrelated locally, but correlations are indirectly accounted for via an on-site repulsion parameter, U. This simplification decouples the complex interactions between electrons, allowing the many-body problem to be mapped onto an effective single-particle problem. Specifically, the method projects out doubly occupied states, effectively reducing the Hilbert space and introducing a variational parameter that determines the weight of these configurations. The resulting effective Hamiltonian can then be solved more readily, providing an approximate ground state and insights into the system’s behavior, although it often underestimates strong correlation effects.

The Erosion of Bands: The Emergence of Insulating Gaps

Band renormalization, a consequence of electron-electron interactions within a material, fundamentally alters the electronic band structure. These interactions effectively modify the energy associated with each electron, shifting band edges and changing the curvature of energy bands. A key result of this renormalization is the formation of a mobility gap, which represents a range of energies where no electronic states are available for conduction. This gap arises because electron correlations reduce the kinetic energy of electrons, leading to a narrowing of the bandwidth and, consequently, the creation of an insulating region between otherwise conductive bands. The size of the mobility gap is directly related to the strength of the electron correlations present in the material.

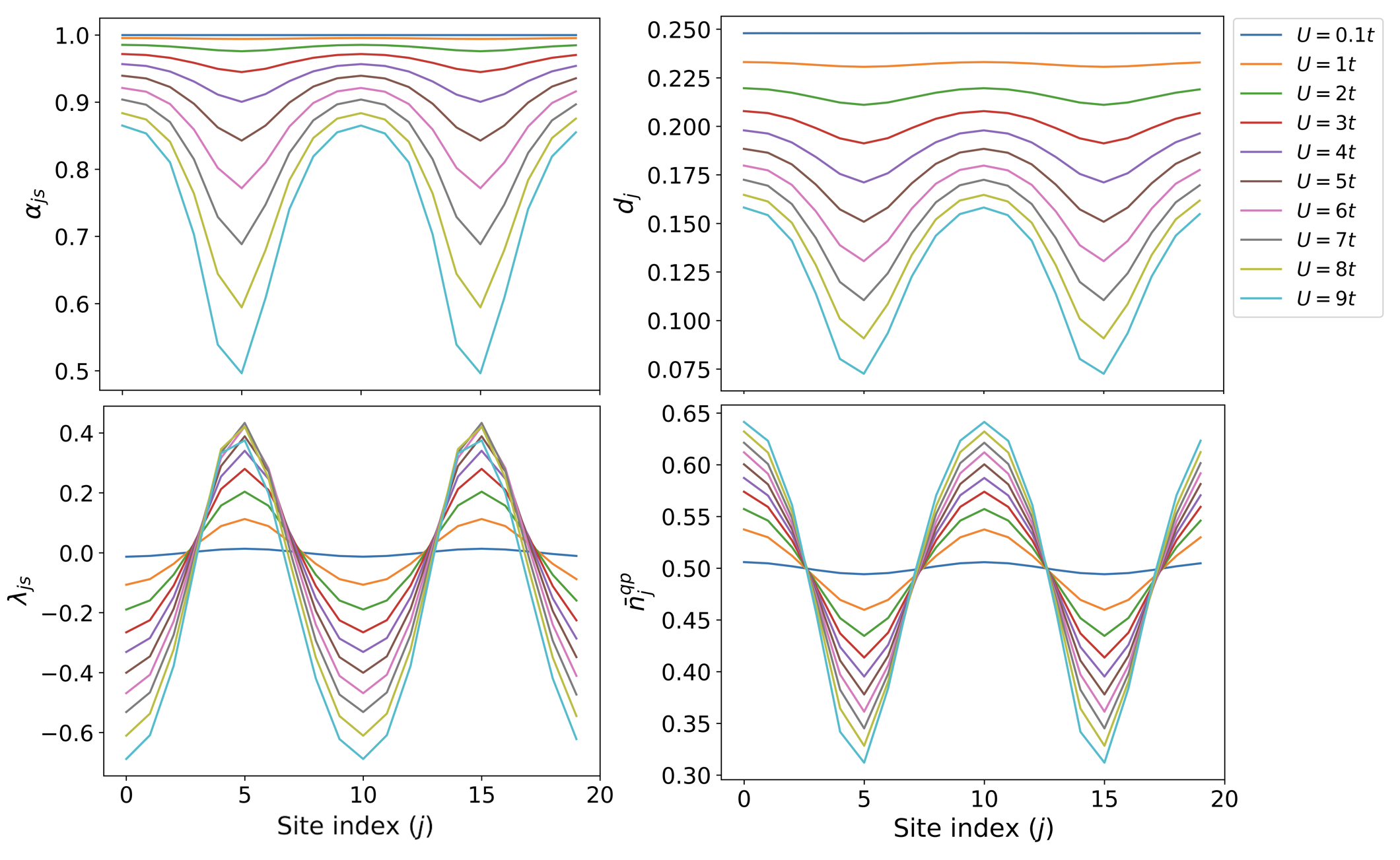

The strength of electron correlations within a material is quantified by parameters such as the Alpha and Lambda parameters. These parameters directly influence the Hopping Integral, which represents the probability of electron tunneling between lattice sites, and the Double Occupancy, indicating the average number of electrons occupying a single lattice site. Specifically, the Alpha parameter scales the hopping integral, reducing its magnitude as correlation strength increases, while the Lambda parameter modifies the on-site energy, influencing the propensity for double occupancy. Changes in both the hopping integral and double occupancy due to these parameters contribute to renormalization of the electronic bands and, consequently, to alterations in the material’s electronic properties, including the formation or reduction of a Mobility Gap.

Experimental results indicate that electron correlation effects are capable of closing the mobility gap separating the ν = 1 and ν = 2 Landau levels. This gap closure is associated with band bending resulting from spatial modulations within the electronic structure. While band bending alone, parameterized by site renormalization values λj,s, can influence band structure, it is demonstrably insufficient to fully close the mobility gap without the concurrent presence of electron correlation effects; the observed gap closure requires both phenomena to be present and interacting.

From Microscopic Interactions to Macroscopic Conductivity

The Kubo formula offers a rigorous, first-principles approach to determining a material’s transverse conductivity, bridging the gap between the microscopic behavior of electrons and the macroscopic property observed in electrical measurements. Rather than relying on empirically-derived values or simplifying assumptions, this linear response theory calculates conductivity from the current-current correlation function, effectively averaging over all possible quantum states weighted by their probability. This necessitates a detailed understanding of the system’s Hamiltonian and the velocity operator \hat{v}, which dictates how electrons respond to an applied electric field. Consequently, the Kubo formula allows researchers to predict conductivity based solely on the material’s fundamental properties, offering insights into how factors like temperature, disorder, and electron interactions influence charge transport – and providing a powerful tool for materials design and characterization.

The calculation of electrical conductivity fundamentally hinges on accurately describing how electrons move within a material’s lattice, a description captured by the Velocity Operator. This operator isn’t simply a measure of speed; it encapsulates the complex interplay between an electron’s momentum and the periodic potential created by the atomic nuclei. Specifically, the Velocity Operator determines how an electron responds to an applied electric field, considering not just its intrinsic velocity but also how the lattice structure scatters and redirects its motion. A precise understanding of this operator, often expressed in terms of momentum \hat{p} and the crystal momentum \vec{k} , is crucial for linking microscopic properties – the behavior of individual electrons – to the macroscopic property of conductivity. Without a detailed description of electron motion through the lattice, any attempt to calculate conductivity from first principles would be incomplete, failing to account for the essential quantum mechanical interactions that govern electron transport.

Theoretical investigations reveal how electron interactions can undermine the precise quantization observed in the Integer Quantum Hall Effect. By integrating the Hubbard model – which describes electron-electron repulsion – with the concept of band renormalization, and then applying the Kubo formula to calculate conductivity, researchers can predict the extent of this degradation. This approach demonstrates that electron correlations specifically impact the filling of Landau levels, leading to a gradual breakdown of the quantized Hall resistance. Crucially, this mechanism differs from the degradation caused by site disorder – imperfections in the material – which uniformly affects all Landau levels, whereas correlations selectively alter specific levels and their associated conductivity, offering a pathway to distinguish between these two sources of disorder in experimental observations.

The pursuit of pristine, isolated systems – a hallmark of condensed matter physics – often overlooks the inherent messiness of reality. This research, detailing the degradation of the integer quantum Hall effect due to electron correlation, underscores this point. It isn’t merely a failure of calculation, but a prophecy fulfilled; the attempt to optimize for a specific, idealized state – strong quantization and a wide mobility gap – inevitably introduces vulnerabilities. As Epicurus observed, “It is not possible to live pleasantly without living prudently, honorably, and justly.” Similarly, a system striving for perfect isolation neglects the inevitability of interaction, and the resulting complexity. Scalability, in this context, isn’t about building bigger; it’s about acknowledging the inherent fragility of even the most elegantly conceived structures.

The Horizon Beckons

The observation that strong electron correlation can diminish the integer quantum Hall effect isn’t a failure of the theory, but a symptom of its ambition. The pursuit of pristine topological phases often fixates on isolation – on systems perfectly divorced from perturbation. Yet, this work suggests the opposite: that the very robustness of these states lies not in their resistance to change, but in their capacity to forgive it. The closing of the mobility gap isn’t a collapse, but a reconfiguration – a bending of the landscape in response to the inherent messiness of many-body interactions.

The Gutzwiller approximation, while illuminating, remains a simplification. Future work will inevitably explore more sophisticated treatments of correlation, acknowledging that electrons aren’t simply particles occupying discrete levels, but waves rippling across a complex potential. The challenge isn’t to eliminate the bending, but to understand its geometry – to map the contours of this newly revealed landscape and predict where stability might unexpectedly emerge.

A system isn’t a machine to be engineered, but a garden to be tended. This research doesn’t deliver a blueprint for a perfect quantum Hall device, but a warning: the pursuit of control is often an exercise in self-deception. True resilience will not be found in isolating components, but in cultivating a delicate balance – allowing the system to adapt, to yield, to the inevitable pressures of its environment.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.16453.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Enshrouded: Giant Critter Scales Location

- All Carcadia Burn ECHO Log Locations in Borderlands 4

- Best Finishers In WWE 2K25

- All Shrine Climb Locations in Ghost of Yotei

- Poppy Playtime 5: Battery Locations & Locker Code for Huggy Escape Room

- Top 10 Must-Watch Isekai Anime on Crunchyroll Revealed!

- Best ARs in BF6

- Best Anime Cyborgs

- Scopper’s Observation Haki Outshines Shanks’ Future Sight!

- 10 Co-Op Games With 90+ Scores On Open-Critic

2026-01-26 23:14