Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research defines the limits of efficient data aggregation, revealing how to dramatically reduce the number of responses needed for weighted polynomial computations.

This paper establishes fundamental limits for coded polynomial aggregation, demonstrating performance gains over traditional individual decoding approaches through optimized orthogonality conditions.

Computing weighted polynomial aggregations efficiently is challenged by the need for numerous worker responses, particularly in distributed systems susceptible to stragglers. This paper, ‘Fundamental Limits of Coded Polynomial Aggregation’, addresses this limitation by extending coded polynomial aggregation to straggler-aware settings, establishing a framework where exact recovery requires responses only from a pre-specified set of non-straggler workers. Our central result demonstrates that exact recovery is achievable with fewer responses than traditional individual decoding, fundamentally characterized by the intersection structure of admissible non-straggler patterns and an associated threshold. Ultimately, this work asks whether exploiting this intersection structure can unlock even more robust and efficient distributed computation of polynomial functions.

The Inevitable Bottleneck: Scaling Beyond the Limits of Computation

The relentless growth of data-intensive applications-from machine learning and scientific simulations to financial modeling and real-time analytics-has propelled a significant shift towards large-scale distributed computation. This paradigm, while offering immense processing power, introduces substantial communication bottlenecks as data must be exchanged between numerous worker nodes. As the number of processors increases, the sheer volume of inter-process communication quickly overwhelms network bandwidth, leading to diminishing returns and severely impacting overall performance. This challenge isn’t simply about faster networks; it’s a fundamental limitation imposed by the architecture itself, requiring innovative strategies to minimize data transfer and maximize computational efficiency. Consequently, researchers are actively exploring techniques to overcome these bottlenecks and unlock the full potential of distributed systems.

As computational demands escalate, conventional distributed computing architectures face inherent limitations in scalability. These systems often rely on frequent data exchange between processing nodes, a practice that becomes increasingly inefficient as the number of workers expands. The core issue lies in the growing communication overhead – the time and resources dedicated to transmitting data – which quickly outpaces the gains from adding more processors. Consequently, performance plateaus and even declines, a phenomenon known as Amdahl’s Law in action, where the sequential portion of a task ultimately limits overall speedup. This bottleneck arises because traditional approaches treat data distribution as a separate step from computation, creating a constant need for synchronization and data transfer that hinders the ability to effectively harness parallel processing power.

Coded computing presents a novel approach to scaling computational tasks by intentionally introducing redundancy into the data processing workflow. Instead of each worker requiring all necessary data, coded computing leverages techniques inspired by error-correcting codes – similar to those used in data transmission – to distribute data in a way that allows workers to perform computations on subsets. This strategic redundancy minimizes the communication overhead typically associated with large-scale distributed systems, as workers can reconstruct missing information locally. The result is a significant reduction in data exchange, enabling greater parallelization and ultimately improving overall computational efficiency, even as the number of participating workers increases. This method effectively trades a modest increase in computational load for a substantial decrease in communication bottlenecks, offering a promising path toward more scalable and robust data processing.

Polynomial Codes: The Foundation of Resilient Computation

Polynomial codes represent data matrices by mapping matrix elements to the coefficients of one or more polynomials. This transformation allows a matrix, A of size n \times k, to be encoded as a polynomial of degree n-1 with k coefficients. Performing computations on the original matrix then becomes equivalent to polynomial arithmetic – multiplication, addition, and evaluation – which can be significantly more efficient, particularly when leveraging Fast Fourier Transforms (FFTs). This approach reduces the computational complexity of operations like matrix-vector multiplication and allows for data compression, as the entire matrix is represented by a smaller set of polynomial coefficients.

Maximum Distance Separable (MDS) codes are frequently employed in the construction of robust polynomial codes due to their provable error correction guarantees. MDS codes are characterized by achieving the maximum possible Hamming distance for a given code length and dimension, allowing for the correction of up to t = \lfloor \frac{n-k}{2} \rfloor errors, where n is the code length and k is the dimension. When integrated into polynomial codes, data is encoded as coefficients of a polynomial, and error correction leverages the properties of the MDS code to reconstruct the original data even with a certain number of corrupted coefficients. This structured approach provides a mathematically rigorous framework for ensuring data integrity and reliability in computational processes.

Encoding data using polynomial codes enables distributed computation by allowing workers to operate on encoded coefficients, rather than the original data. This approach minimizes communication overhead because workers only need to exchange a limited number of encoded shares – typically determined by the degree of the polynomial and the number of workers. Specifically, evaluating a polynomial at multiple points distributes the data without requiring transmission of the entire dataset. Computations are then performed locally on these evaluated values, and only the results of these local computations need to be aggregated, significantly reducing communication costs compared to traditional distributed computation models where the entire dataset would need to be shared.

Advanced Coding Schemes: Optimizing for Practicality

PolyDot and MatDot codes represent advancements in interpolation-based coded computing, specifically designed to manage the inherent trade-offs between computational complexity and communication overhead. These schemes achieve performance optimization by strategically altering the coding matrix construction. PolyDot codes utilize polynomial constructions, while MatDot codes employ matrix-based approaches, both enabling a flexible adjustment of the coding rate and field size. This allows for tailoring the coding scheme to specific network and device constraints; for example, reducing communication costs by accepting increased computational load at the decoding stage, or vice-versa. The objective is to minimize the overall latency and energy consumption of the computation, particularly in distributed settings where data transmission is a significant bottleneck.

Lagrange Coded Computing utilizes Lagrange interpolation, a method for constructing a polynomial that passes through a given set of data points, to enable coded computation. This approach, when combined with Chebyshev polynomials, significantly improves numerical stability and computational efficiency. Chebyshev polynomials are orthogonal polynomials that minimize the maximum absolute value of a polynomial over a given interval, reducing the impact of rounding errors during interpolation. The use of these polynomials results in a more well-conditioned interpolation problem, particularly crucial for large datasets or noisy data. This combination allows for reliable reconstruction of the original data from coded data, facilitating accurate computations even in the presence of errors.

Berrut-approximated Coded Computing represents an advancement in interpolation-based coded computation by utilizing Berrut’s algorithm to refine the polynomial approximations used in data reconstruction. This method specifically addresses numerical instability inherent in traditional interpolation schemes, particularly when dealing with noisy or incomplete data. By employing a carefully chosen approximation order, Berrut-approximated methods minimize the propagation of errors during the interpolation process, resulting in improved computational accuracy and a more robust solution. The technique’s efficacy stems from its ability to control the condition number of the interpolation matrix, thereby mitigating the impact of rounding errors and enhancing the overall reliability of the computed results.

Decoding Strategies and System Impact: A Reduction in Responses

Coded Polynomial Aggregation, or CPA, presents a novel computational framework designed to efficiently handle weighted aggregations of polynomial computations. This technique fundamentally shifts the approach to computation by encoding polynomial functions and distributing the evaluation across multiple workers. Instead of directly computing a weighted sum of polynomials, CPA leverages coding principles to enable a collective computation where individual responses are combined to reconstruct the final result. The core benefit lies in optimized decoding; through carefully designed coding schemes, CPA minimizes the computational burden and communication overhead associated with traditional methods. This is achieved by transforming the problem into a system of equations that can be efficiently solved, even with potential errors or failures in individual worker responses, ultimately leading to a substantial performance gain for complex polynomial computations.

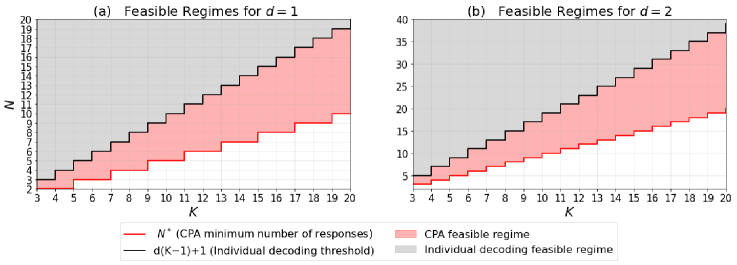

A core challenge in coded computation lies in minimizing the number of responses required to reliably reconstruct a result, a value known as the Minimum Responses. This work establishes a significant reduction in this metric for linear computations utilizing Coded Polynomial Aggregation (CPA). Specifically, the research demonstrates that, through strategic coding schemes, successful decoding can be achieved with just \lfloor(K-1)/2 \rfloor + 1 responses, where K represents the number of workers involved. This represents a substantial improvement over traditional individual decoding methods, which typically necessitate d(K-1)+1 responses, and highlights the efficiency gains achievable through optimized coding strategies in distributed computation systems.

Coded Polynomial Aggregation (CPA) substantially reduces the communication overhead in weighted polynomial computations by minimizing the required number of responses from the computation server. For polynomial degrees of 2 or greater, CPA achieves this efficiency by requiring only (d-1)(K-1)+1 responses, where ‘d’ represents the polynomial degree and ‘K’ denotes the number of clients. This represents a marked improvement compared to traditional individual decoding methods, which necessitate d(K-1)+1 responses. The reduction in required communication not only accelerates computation but also lowers associated costs, particularly in scenarios involving large-scale polynomial evaluations or distributed computing environments, making CPA a compelling solution for optimizing system performance.

Coded Polynomial Aggregation (CPA) benefits significantly from the integration of advanced techniques such as Individual Decoding and Gradient Coding, leading to substantial improvements in computational efficiency. Individual Decoding streamlines the process by allowing for the independent decoding of individual responses, thereby reducing overall complexity compared to traditional methods. Furthermore, Gradient Coding optimizes the aggregation process by leveraging gradient information, enabling a more focused and efficient computation of weighted sums. These combined approaches not only minimize the resources required for decoding but also contribute to a noticeable enhancement in the overall performance of CPA systems, particularly when dealing with high-degree polynomials or large datasets. The synergistic effect of these techniques positions CPA as a powerful tool for secure and efficient computation in various applications.

Toward Adaptive and Secure Coded Computing: The Future of Resilience

Coded computing, traditionally focused on error correction, is being reframed through a learning-theoretic lens as a core encoder-decoder design challenge. This approach casts the problem not as simply preventing errors, but as optimizing a system to minimize the mean\ squared\ error between the desired output and the computed result. By treating computation as a signal processing task, researchers can apply tools from machine learning and statistical inference to create coding schemes tailored to specific computational demands. This paradigm shift allows for the development of adaptive coding strategies, moving beyond fixed error-correcting codes to schemes that dynamically adjust to the characteristics of the data and the computational process itself, ultimately enhancing both the reliability and efficiency of computation.

Within the learning-theoretic framework of coded computing, smoothing splines offer a powerful mechanism for crafting coding schemes tailored to precise computational needs. These splines, functions defined by piecewise polynomials, effectively balance fidelity to the desired computation with the robustness conferred by coding. By adjusting the spline’s smoothness – controlled by a penalty parameter – researchers can optimize the trade-off between minimizing the mean squared error of the computation and maximizing the code’s ability to correct errors introduced during processing. This approach moves beyond generic coding strategies, allowing for the creation of codes specifically designed to enhance performance in scenarios where computational demands and error profiles are well-defined, effectively adapting the coding scheme to the nuances of each application.

Entangled Polynomial Codes represent a significant advancement in safeguarding data during computation, building upon the established principles of polynomial coded computing. These codes move beyond simple error correction to actively protect the privacy of the data being processed. By leveraging techniques from quantum information theory – specifically, entanglement – the codes distribute data fragments across multiple polynomial representations in a way that prevents any single computing node from accessing the complete, raw information. This ensures that even if a node is compromised, the sensitive data remains protected. The resulting computations are performed on these fragmented representations, and only the final, aggregated result is revealed, preserving data confidentiality throughout the entire process. This approach is particularly valuable in scenarios like federated learning or secure multi-party computation, where data owners wish to collaborate without exposing their individual datasets.

The pursuit of minimizing worker responses, as detailed in this work on coded polynomial aggregation, echoes a deeper truth about complex systems. It isn’t about achieving perfect efficiency-a static ideal-but about understanding the inevitable trade-offs inherent in distributed computation. As G.H. Hardy observed, “The most potent weapon in the hands of the problem-solver is the conviction that there is a solution.” This conviction, however, isn’t about finding a solution, but about accepting that every ‘solution’ merely shifts the locus of complexity. The work demonstrates this through its focus on minimizing responses-a local optimization-while implicitly acknowledging the ever-present potential for unforeseen interactions and emergent behaviors within the aggregation process. Long stability in response rates would be a sign of a hidden disaster, a failure to adapt to the evolving demands of the system.

The Horizon Recedes

This work, concerning the limits of coded polynomial aggregation, does not offer a destination, but rather a sharper map of the surrounding swamp. The reduction in worker responses is a temporary reprieve, a localized decrease in entropy. It merely shifts the burden – the inevitable cost of computation is not avoided, only deferred, and potentially manifested elsewhere in the system. Every optimization creates a new surface for failure to bloom.

The orthogonality conditions, while necessary, are not sufficient. They describe what can be computed efficiently, not what should be. A perfectly efficient aggregation scheme is a beautiful artifact, but it says nothing of the value of the data being aggregated, or the fragility of the assumptions embedded within the polynomials themselves. One suspects the true limits lie not in the coding, but in the very nature of the functions being evaluated – a chaotic system will always resist perfect representation.

Future work will undoubtedly chase ever-smaller response counts, seeking the mythical ‘minimum’. But perhaps the more fruitful path lies in embracing the inherent messiness of distributed computation. Instead of striving for a flawless architecture, the field should focus on building systems resilient enough to withstand inevitable imperfection – systems that degrade gracefully, rather than collapsing spectacularly. Order, after all, is just a temporary cache between failures.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.10028.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Jujutsu Kaisen Modulo Chapter 18 Preview: Rika And Tsurugi’s Full Power

- How to Unlock the Mines in Cookie Run: Kingdom

- Upload Labs: Beginner Tips & Tricks

- ALGS Championship 2026—Teams, Schedule, and Where to Watch

- Top 8 UFC 5 Perks Every Fighter Should Use

- Jujutsu: Zero Codes (December 2025)

- How to Unlock & Visit Town Square in Cookie Run: Kingdom

- Roblox 1 Step = $1 Codes

- Mario’s Voice Actor Debunks ‘Weird Online Narrative’ About Nintendo Directs

- The Winter Floating Festival Event Puzzles In DDV

2026-01-18 19:59