Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new paradigm shifts the focus from transmitting data to synchronizing internal states, promising more efficient communication in challenging environments.

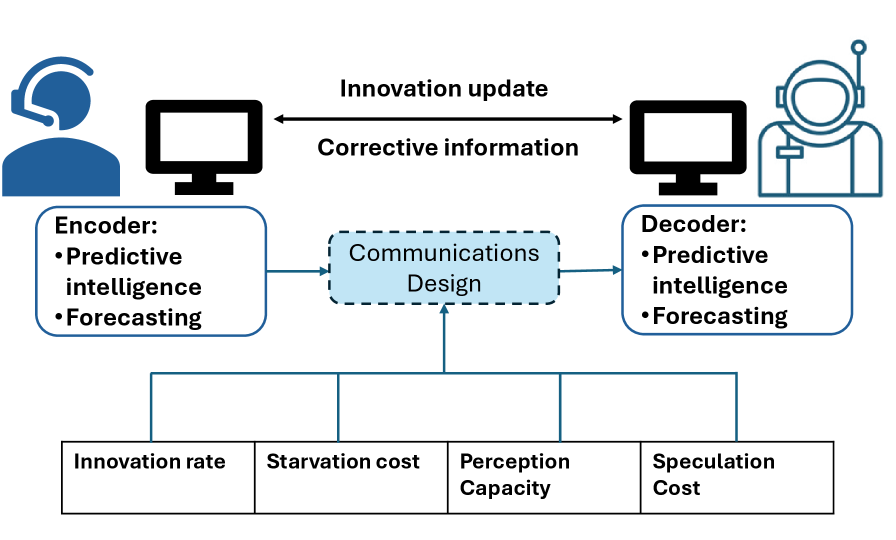

This review explores Predictive-State Communication, a method that transmits only the ‘innovation’ required to reconcile predicted and actual states, addressing limitations in delayed or bandwidth-constrained systems.

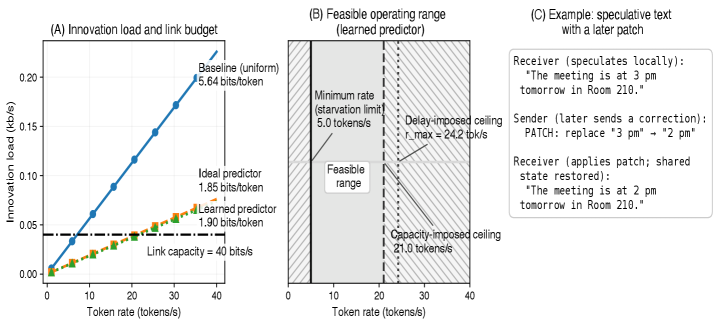

Traditional communication theory centers on reliably transmitting symbol sequences, yet this framework becomes increasingly limiting when both sender and receiver possess strong predictive models. This paper, ‘Predictive-State Communication: Innovation Coding and Reconciliation under Delay’, proposes a paradigm shift, focusing on transmitting only the ‘innovations’-the minimal corrections needed to reconcile a receiver’s predicted state with the transmitter’s actual trajectory. By framing communication as state synchronization rather than symbol transport, and accounting for model mismatch via cross-entropy, we identify a feasibility region bounded by capacity, delay, and perceptual continuity-a ‘perception-capacity band’. Could this approach unlock fundamentally more efficient communication strategies in delay-sensitive applications, particularly those leveraging increasingly powerful generative models?

The Erosion of Fidelity: Beyond Simple Reproduction

The prevailing paradigm of communication, largely defined by Claude Shannon’s work, centers on the accurate reproduction of a signal at its destination. This model treats information as a series of bits to be faithfully transmitted, prioritizing technical fidelity over the actual meaning conveyed. Consequently, systems are often optimized for minimizing transmission errors, even if the semantic content is subtly altered or requires significant processing to reconstruct the original intent. While remarkably effective for digital data, this approach can be surprisingly inefficient when dealing with complex or nuanced information, as it necessitates increasingly sophisticated error correction techniques to maintain signal integrity – a process that can overshadow the core message itself. The focus on bit-perfect transmission, therefore, sometimes obscures the fundamental goal of communication: establishing shared understanding between sender and receiver.

Traditional communication systems, striving for perfect signal replication, encounter significant hurdles when operating across imperfect channels. As bandwidth diminishes or noise increases – commonplace in real-world scenarios like wireless networks or deep space communication – the demand for sophisticated error correction mechanisms escalates dramatically. These techniques, while attempting to reconstruct the original signal, add substantial overhead, effectively reducing the rate of meaningful information transfer. The complexity of these codes grows exponentially with the severity of the channel impairments, ultimately reaching a point of diminishing returns where the resources dedicated to error correction outweigh the benefits of transmitting the core message. This illustrates a fundamental limitation: simply trying to ‘force’ bits through a noisy channel isn’t a scalable solution, and highlights the need for approaches that prioritize robust understanding over flawless reproduction.

The prevailing paradigm in communication, rooted in Shannon’s model, often equates success with accurate signal reproduction, but this approach reveals inherent limitations when encountering real-world conditions like interference or constrained bandwidth. Increasingly complex error correction methods attempt to salvage data fidelity, yet a more profound rethinking of communication’s core objective is necessary. The focus should shift from simply transmitting bits without error to establishing shared understanding between sender and receiver. This means prioritizing the conveyance of meaning, even if it requires sacrificing strict bit-perfect transmission. Such a transition acknowledges that communication isn’t merely a technical problem of signal integrity, but a cognitive process dependent on mutual context, interpretation, and the successful negotiation of meaning – a move that promises more robust and efficient communication systems designed around comprehension, rather than replication.

Predictive Alignment: Reconciling Divergent States

Predictive State Communication (PSC) diverges from traditional communication paradigms by prioritizing the maintenance of internally consistent, predictive models within each endpoint. Rather than focusing on direct message exchange, PSC assumes endpoints possess a shared understanding of the environment, formalized as a probabilistic model. Each endpoint continuously refines this model based on its local observations and utilizes it to anticipate the states of other endpoints. This allows for a shift from transmitting raw data to transmitting information about the difference between predicted and observed states, effectively leveraging prior knowledge and minimizing redundant data transfer. The accuracy of these individual predictive models is central to the efficiency of the system; improved prediction directly translates to reduced communication overhead.

Predictive State Communication (PSC) optimizes bandwidth utilization by transmitting only the difference between a receiving endpoint’s predicted sensory input and its actual observation; these differences are termed ‘innovations’. Rather than sending complete state vectors representing the entire environment, PSC focuses on conveying only the information that changes the receiver’s existing understanding. This approach leverages the principle that a significant portion of environmental state is often predictable, rendering redundant the transmission of already-known information. The size of these innovation signals is directly related to the accuracy of the predictive model; more accurate predictions result in smaller innovation signals and, consequently, reduced bandwidth requirements. This contrasts with traditional communication methods which transmit absolute values, regardless of prior knowledge or predictability.

The efficiency of Predictive State Communication (PSC) is directly correlated to the cross-entropy rate, denoted as h. A low h value signifies that the predictive models at communicating endpoints are highly accurate, meaning predictions closely match observed states. Consequently, the ‘innovation’ – the difference between prediction and observation that requires transmission – is minimized. This reduction in innovation size directly translates to lower bandwidth requirements, as less data needs to be exchanged to maintain state synchronization. Therefore, PSC performs optimally in environments where predictability is high and the cross-entropy rate is consistently low, maximizing communication efficiency and minimizing data transfer.

Predictive State Communication (PSC) diverges from traditional communication paradigms by conceptualizing data exchange not as message transmission, but as the active alignment of internal states between endpoints. Rather than focusing on the content of a message, PSC prioritizes achieving a shared, accurate representation of the environment. This is accomplished by each endpoint maintaining a predictive model and transmitting only the minimal information needed to correct prediction errors in the receiver’s model. Consequently, successful communication, within the PSC framework, is defined by the degree of state convergence-how closely the internal models of communicating entities match the actual, shared environment – rather than the faithful delivery of symbolic data. This reframing has implications for system design, emphasizing model accuracy and efficient error correction as primary performance metrics.

Patching the Disconnect: Mechanisms for State Correction

Predictive State Correction (PSC) employs ‘patches’ as a mechanism for efficiently communicating corrections to a receiver’s predicted state. These patches are not full state transfers, but rather compact data structures representing the minimal necessary adjustments to reconcile the receiver’s provisional trajectory with the sender’s current understanding. This approach minimizes bandwidth usage and computational cost compared to transmitting complete state updates, as only the differences between states are communicated. The size of these patches is directly related to the magnitude of the correction needed and the complexity of the state space, but are designed to be significantly smaller than the full state representation.

Patch construction in Predictive State Correction (PSC) relies on token edit scripts, which specify the precise alterations needed to align the receiver’s current predicted state with the sender’s corrected state. These scripts operate on a tokenized representation of the trajectory, identifying only the minimal set of token modifications – insertions, deletions, or substitutions – required for reconciliation. This approach minimizes data transmission overhead and computational cost, as only the differences between states are communicated. The granularity of these token edits directly impacts the precision of the correction and the efficiency of the patching process; finer granularity allows for more accurate corrections but increases script complexity and size.

Predictive State Control (PSC) implements rollback mechanisms as a fault tolerance strategy. When discrepancies arise between predicted and actual states, or when confidence in the current prediction falls below a defined threshold, the system reverts to a previously stored ‘anchor’ state. These anchor states represent known, stable system configurations, serving as recovery points. The rollback process involves restoring the system to the anchor state and re-initializing the prediction process from that point, effectively discarding the erroneous trajectory. This ensures system stability and prevents the propagation of errors by providing a defined means of returning to a known good configuration.

The State Identifier (StateID) is a unique value assigned to each predictive state within the Predictive State Correction (PSC) framework, serving as a critical component for maintaining compatibility and consistency between communicating endpoints. This identifier functions as a version number, enabling endpoints to verify whether their internal state representations are synchronized before applying corrections. Specifically, the receiver utilizes the StateID to determine if the incoming patch is applicable to its current state; a mismatch indicates that the receiver’s state has diverged, potentially due to unreceived updates or errors, and the patch is disregarded to prevent inconsistencies. Successful application of a patch requires a matching StateID, ensuring that both sender and receiver are operating on the same baseline understanding of the predicted trajectory.

The Language of Prediction: Quantifying Innovation Efficiency

Predictive State Coding (PSC) is fundamentally linked to the cross-entropy rate, which represents a theoretical lower bound on the required innovation rate for effective prediction. This rate, derived from information theory, quantifies the average minimum number of bits necessary to encode each incoming sensory token, given the model’s current predictive distribution. A lower cross-entropy rate indicates a more efficient predictive model, requiring less information to represent unexpected sensory input – or ‘innovation’. Conversely, a higher rate signifies that the model struggles to predict incoming data, necessitating a greater innovation load to maintain accurate state estimation. Therefore, minimizing the cross-entropy rate is paramount to achieving efficient and feasible PSC implementations, as it directly dictates the demands placed on the system’s capacity to process and encode novel information. H(p,q) = - \sum_{x} p(x) \log q(x), where p(x) is the true distribution and q(x) is the predicted distribution.

Statistical language models, specifically n-gram models like bigram models, are utilized to estimate the theoretical minimum innovation rate in Predictive State Coding (PSC) by quantifying the predictability of sequential data. These models operate on the principle that the probability of a token appearing is dependent on the preceding token(s); a highly predictable sequence will have a lower cross-entropy rate. The bigram model, for instance, estimates the probability of a token given the immediately preceding token based on observed frequencies in a training corpus. This probability distribution is then used to calculate the cross-entropy, H(p,q), where p is the true distribution of tokens and q is the distribution predicted by the bigram model. The resulting cross-entropy value represents the average number of bits required to encode each token, providing a quantifiable measure of the information content and, consequently, the innovation load that the PSC system must handle.

Cross-entropy, in the context of Predictive State Coding (PSC), serves as a quantifiable measure of information content and, consequently, innovation load. Specifically, it represents the expected average number of bits required to optimally encode a given token, assuming a probability distribution derived from the model’s predictions. A higher cross-entropy value indicates greater uncertainty in the prediction and, therefore, a larger innovation load – meaning more information needs to be transmitted to correct the prediction error. Formally, cross-entropy H(p,q) between the true distribution p(x) and the predicted distribution q(x) is calculated as H(p,q) = - \sum_{x} p(x) \log q(x). This value directly informs the minimum number of bits necessary to represent the information content of each token, establishing a theoretical lower bound on the information transfer rate required for effective prediction and coding.

The practical implementation of Predictive State Control (PSC) is fundamentally limited by the ‘link capacity’ C_{innov}, which represents the maximum rate at which innovative information can be reliably transmitted from the predictor to the controller. This capacity, typically measured in bits per time step, dictates the upper bound on the achievable innovation rate; exceeding C_{innov} leads to instability or performance degradation. The link capacity is determined by factors such as the bandwidth of the communication channel and the noise characteristics of the system. Therefore, the design of a PSC system must account for C_{innov} to ensure that the innovation signal remains within the system’s transmission limits, directly impacting the achievable prediction horizon and control performance.

Predictive State Control (PSC) and Kalman Filtering represent distinct paradigms in state estimation despite both addressing the problem of inferring system states from noisy observations. Kalman Filtering is a recursive algorithm that estimates the state of a linear dynamic system, assuming Gaussian noise and relying on the covariance matrix to propagate uncertainty. Conversely, PSC focuses on minimizing the expected surprisal-or cross-entropy-between the predicted and actual system behavior, operating without explicit covariance estimation. This difference leads to fundamentally different update rules; Kalman Filtering provides a statistically optimal estimate given its assumptions, while PSC aims to directly control the system to maximize predictability and minimize information loss, making it suitable for non-Gaussian and nonlinear systems where Kalman Filtering’s optimality guarantees do not hold.

Beyond Transmission: The Future of Predictive Communication

Predictive Semantic Communication (PSC) fundamentally shifts communication paradigms by leveraging the power of predictive models, notably Large Language Models (LLMs), to anticipate receiver needs and drastically reduce transmitted data. Instead of sending complete messages, PSC transmits only the information necessary to correct the receiver’s predictions, capitalizing on the inherent redundancies within data streams like language or video. This approach promises a robust communication system, particularly valuable in bandwidth-constrained or unreliable environments, as the receiver can continue to operate on provisional data even with intermittent disruptions. By prioritizing semantic alignment-ensuring the meaning is conveyed-over perfect bit-for-bit replication, PSC opens avenues for highly efficient and resilient communication, potentially revolutionizing applications ranging from real-time video conferencing to remote device control.

The inherent efficiency of Predictive Semantic Communication (PSC) – delivering information before full confirmation – introduces a critical element of risk known as ‘speculation cost’. This cost arises because provisional outputs, acted upon before complete validation, may require subsequent correction. If the receiver integrates provisional data into a process and that data proves inaccurate, a correction isn’t merely a matter of updating a display; it demands a reversal of actions, potentially incurring significant practical or economic consequences. The magnitude of this speculation cost is directly tied to the sensitivity of the application – a self-driving car, for example, faces far higher costs from misinterpreting provisional sensor data than a system displaying stock quotes. Consequently, PSC systems must carefully balance the benefits of reduced latency against the potential repercussions of acting on imperfect information, effectively quantifying and minimizing the impact of these inevitable corrections.

The effectiveness of Provisional Semantic Communication (PSC) hinges on a critical parameter: the speculation horizon, denoted as H. This value represents the maximum duration a receiver can confidently act upon preliminary data before requiring a formal reconciliation with the sender. A longer H allows for greater continuity and reduced transmission overhead, as the receiver can extrapolate from provisional information for an extended period; however, it simultaneously increases the potential cost of correction should errors accumulate over time. Conversely, a shorter H minimizes the risk of acting on flawed data, but necessitates more frequent communication to replenish provisional information, potentially straining bandwidth. Optimizing H therefore becomes a delicate balancing act, directly influencing the trade-off between the cost of continuous operation and the expense of rectifying inaccuracies within the communication stream.

A critical challenge in provisional sequential communication (PSC) lies in managing delays to provisional output, a phenomenon termed ‘starvation.’ Prolonged latency between data generation and receipt can significantly degrade performance, as the receiver operates with increasingly outdated information. While minimizing transmission volume is a primary goal of PSC, aggressively prioritizing this can lead to extended starvation periods. This presents a distinct cost, potentially requiring more substantial corrections during reconciliation, or even rendering provisional data unusable. Therefore, system designers must carefully balance the trade-off between minimizing data transmission and ensuring timely delivery of provisional output; a strategy that optimizes for both semantic alignment and responsiveness is crucial to avoid the pitfalls of prolonged starvation and maintain effective communication.

The rollback window, denoted as W, functions as a critical safety net within Predictive Semantic Communication (PSC) systems, defining the maximum amount of previously transmitted, provisional output that can be safely discarded and re-generated during the reconciliation phase. This mechanism addresses inevitable errors in prediction by allowing the receiver to request retransmission of only a limited, recent segment of the communicated stream, rather than requiring a full reset. A smaller W minimizes the cost of correcting errors – reducing retransmission bandwidth – but increases the risk of propagating errors if the initial predictions are significantly flawed. Conversely, a larger window provides greater error resilience but demands more bandwidth for potential corrections. Therefore, optimizing W is a key design challenge, balancing the trade-off between correction cost and the ability to recover from sustained prediction failures, ultimately impacting the overall efficiency and robustness of the communication link.

Predictive Semantic Communication (PSC) envisions a paradigm shift in data transmission, moving beyond simply sending information to proactively anticipating meaning. This approach dramatically reduces the volume of data needing transfer by leveraging the inherent predictability of language and concepts; rather than transmitting every detail, PSC sends only the information necessary to resolve uncertainty in the receiver’s prediction. Crucially, PSC prioritizes semantic alignment – ensuring the receiver accurately understands the intended meaning – even if it requires initial provisional outputs subject to later correction. This focus on meaning, combined with minimized data, promises a future where communication is not only bandwidth-efficient but also remarkably resilient to noise and interruptions, potentially revolutionizing applications ranging from real-time video conferencing to reliable data transfer across constrained networks.

The pursuit of Predictive-State Communication, as detailed in the research, inherently acknowledges the transient nature of information and systems. Every transmission, every prediction, is a temporary alignment against inevitable divergence. This aligns with Andrey Kolmogorov’s assertion: “The most important things are not what we know, but what we don’t know.” The work effectively frames communication not as the faithful delivery of symbols, but as a constant reconciliation of predicted states-an acknowledgement of inherent uncertainty. The concept of a ‘Feasibility Band’ underscores this, defining the limits within which prediction and innovation can operate before system integrity is compromised. It’s a delicate balance, and resilience, as the research suggests, emerges from adapting to the inevitable drift between prediction and reality-a slow, continuous adjustment rather than a static perfection.

What Lies Ahead?

Predictive-State Communication, as presented, isn’t merely a refinement of existing paradigms; it’s an acknowledgement that all communication is, fundamentally, an exercise in damage control. Every bit transmitted is a correction, a mending of divergent internal models. The elegance of focusing on ‘innovation’-the minimal necessary adjustment-doesn’t erase the inevitability of divergence, only postpones it. The feasibility band, a zone of acceptable prediction error, represents not a solution, but a temporary reprieve. Systems will, inevitably, drift.

Future work must address the cost of prediction itself. Maintaining a receiver’s predictive model isn’t free; computational resources and energy are expended in anticipating the transmitter’s state. The true metric isn’t bandwidth saved, but the total energetic cost of synchronization. Furthermore, the anchoring mechanism, while practical, implies a reliance on external truth – a dangerous assumption. What happens when the anchor itself begins to drift? Every bug is a moment of truth in the timeline, revealing the fragility of assumed stability.

This work opens a path toward communication systems that age more gracefully, accepting drift as an inherent property rather than fighting it. But technical debt is the past’s mortgage paid by the present. The pursuit of ever-more-accurate prediction risks creating systems so brittle that even minor disturbances trigger catastrophic failure. The challenge isn’t to eliminate divergence, but to design systems that can absorb it-to build resilience into the very fabric of communication.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.10542.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Epic Games Store Free Games for November 6 Are Great for the Busy Holiday Season

- EUR USD PREDICTION

- How to Unlock & Upgrade Hobbies in Heartopia

- Battlefield 6 Open Beta Anti-Cheat Has Weird Issue on PC

- Sony Shuts Down PlayStation Stars Loyalty Program

- The Mandalorian & Grogu Hits A Worrying Star Wars Snag Ahead Of Its Release

- ARC Raiders Player Loses 100k Worth of Items in the Worst Possible Way

- Unveiling the Eye Patch Pirate: Oda’s Big Reveal in One Piece’s Elbaf Arc!

- TRX PREDICTION. TRX cryptocurrency

- Xbox Game Pass September Wave 1 Revealed

2026-02-12 19:12